The National Life Story Collection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Draft Paper Elisabete Mendes Silva Polytechnic Institute of Bragança

Draft paper Elisabete Mendes Silva Polytechnic Institute of Bragança-Portugal University of Lisbon Centre for English Studies, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Portugal [email protected] Power, cosmopolitanism and socio-spatial division in the commercial arena in Victorian and Edwardian London The developments of the English Revolution and of the British Empire expedited commerce and transformed the social and cultural status quo of Britain and the world. More specifically in London, the metropolis of the country, in the eighteenth century, there was already a sheer number of retail shops that would set forth an urban world of commerce and consumerism. Magnificent and wide-ranging shops served householders with commodities that mesmerized consumers, giving way to new traditions within the commercial and social fabric of London. Therefore, going shopping during the Victorian Age became mandatory in the middle and upper classes‟ social agendas. Harrods Department store opens in 1864, adding new elements to retailing by providing a sole space with a myriad of different commodities. In 1909, Gordon Selfridge opens Selfridges, transforming the concept of urban commerce by imposing a more cosmopolitan outlook in the commercial arena. Within this context, I intend to focus primarily on two of the largest department stores, Harrods and Selfridges, drawing attention to the way these two spaces were perceived when they first opened to the public and the effect they had in the city of London and in its people. I shall discuss how these department stores rendered space for social inclusion and exclusion, gender and race under the spell of the Victorian ethos, national conservatism and imperialism. -

Trade Marks Decision (O/442/10)

O-442-10 TRADE MARKS ACT 1994 IN THE MATTER OF REGISTRATION NO 1284798 IN THE NAME OF PAMPLEMOUSSE LIMITED IN RESPECT OF THE TRADE MARK: ANONYMOUS IN CLASS 25 AND AN APPLICATION FOR REVOCATION (NO 82910) ON THE GROUNDS OF NON-USE BY ANONYMOUS LIMITED O-442-10 TRADE MARKS ACT 1994 In the matter of registration no 1284798 in the name of Pamplemousse Limited in respect of the trade mark ANONYMOUS in class 25 and an application (no 82910) by Anonymous Limited for revocation on the grounds of non-use Background 1) Registration 1284798 is for the trade mark ANONYMOUS which stood, until 3 September 2010, in the name of Pamplemousse Limited (“PM”). On this date the register was amended to reflect an assignment from PM to London Uniform Club and Kit Limited (“LUC”) who then changed its name to Pamplemousse Limited (“PM2”). The trade mark is registered in respect of “Articles of clothing included in Class 25”. 2) The trade was originally filed by Richard Shops Ltd on 13 October 1986 and it completed its registration procedure on 22 August 1988. Since filing it has been assigned on a number of occasions. Other than the assignment mentioned in paragraph 1, it is only necessary to record that PM took proprietorship of the registration from a company called Clashforce Limited on 23 June 2000. 3) On 21 June 2007 Anonymous Limited (“AL”) applied for the revocation of the registration under section 46(1)(b) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 (“the Act”). It is claimed that: “It appears from the investigations conducted by the Applicant that there has been no use of the Trade Mark within the period of five years prior to the date of this application to revoke, i.e. -

PEMBROKE BUILDING KENSINGTON VILLAGE Avonmore Road London W14 8DG

PEMBROKE BUILDING KENSINGTON VILLAGE Avonmore Road London W14 8DG 4th floor office TON V ING ILL S Avonmore Rd A N G E E K A315 Kensington A Gardens Stoner Rd B Stanwick Rd C A315 Hyde Park Gate PEMBROKE A3220 BUILDING D E HIGH STREET KENSINGTON LOCATION: A315 The Pembroke Building is located in Kensington Village, Warwiick Road Warwick Gardens Queens Gate between Hammersmith and Kensington, adjacent to Cromwell Road (A4) and just South of Hammersmith KENSINGTON Road. The building is a short walk from West Kensington OLYMPIA Keinsington High Street (4 mins) and Earls Court (12 mins). The Village also benefits from pedestrian entrances from the A4 with Warwiick Road A3220 Earls Court Road vehicular access from Avonmore Road. Olympia Brook Green A219 Shepherds Bush Road Cromwell Road Hammersmith Road A4 4 A315 1 EARLS A3220 HAMMERSMITH 3 A4 COURT Old Brompton Road A3218 5 Talgarth Road Earls Court A4 2 WEST 7 KENSINGTON A3220 BARONS COURT Redclie Gardens 6 Finborough Road WEST North End Rd Queens Club BROMPTON lham Road Fu Charing Lillie Road Chelsea & Cross Westminster Hospital Normand Hospital Park A219 Directory: Lillie Road Local Occupiers: Lillie Road Homestead Rd 1. Tesco Superstore 5. Fortune (Chinese Restaurant) A. Universal Music, C. ArchantA308 A3220 2. Famous Three Kings (pub) 6. Eat-Aroi (Thai Restaurant) ADM Promotions & D. Holler Digital, A308 3. Sainsbury’s Local 7. Curtains Up (pub) Eaglemoss Publications Leo Burnett & Kaplan ad 4. Premier Inn (hotel) & Barons Court Theatre B. CACI Ltd E. Zodiak Media Digital Store CONNECTIVITY: Transport links to Kensington Village are excellent, with Earls Court, West Kensington (District line), Kensington Olympia (District and Mainline) and Barons Court (Piccadilly line) a short walk away providing good links into central London and the West. -

The Garment Industry's Best Kept Secret : Contuined Global

University Honors Program University of South Florida St. Petersburg, Florida CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL Honors Thesis This is to certify that the Honors Thesis of Wyndy Neidholt has been approved by the Examining Committee on May 1,2001 as satisfactory for the thesis requirement for the University Honors Program Examining Committee: Major Professor: Rebecca Johns, Ph.D. Member: Raymond 0. Arsenault, Ph.D. Member: Jay Sokolovsky, Ph.D. THE GARMENT INDUSTRY'S BEST KEPT SECRET: CONTUINED GLOBAL EXPANSIONS OF SWEATSHOPS by Wyndy Neidholt a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the University Honors Program St. Petersburg Campus University of South Florida May, 2001 Thesis Advisor: Professor Rebecca Johns, Ph.D. CONTENTS Introduction .............................................................................................................. 1 Chapter 1: The United States Goverrunent, Industry, and the Return of the Sweatshop.3 Chapter 2: Global Working Conditions and Wages ............. ...................................... 11 Chapter 3: Mexico, the Caribbean, and NAFTA: A Regional Focus ....... - ................20 Chapter 4: Solutions I: Nonprofit, Industry, and the Law .......................................... 39 Chapter 5: Solutions II: Students, Unions, and Consumers ........................................ 53 Conclusions ...................................................................... ......................... .. ... .. .......... 65 References ................................................................................................................ -

12Elgin.Com 12 ELGIN, ELGIN AVENUE LONDON

12 ELGIN, ELGIN AVENUE LONDON 12elgin.com 12 ELGIN, ELGIN AVENUE LONDON 12elgin.com 1 2 THE DEVELOPMENT 12 Elgin Avenue is a 5 storey building which sits on a circa 0.18 acre site offering a luxury residential scheme of 15 apartments. The Development is designed to meet the highest standards of contemporary styling and taste. The site is located on the south side of Elgin Avenue, 90 metres from the Prince of Wales junction and adjacent to the 1970s built Elgin Estate The Computer Generated Images do not represent the exact look and feel of the development. 3 4 The Computer Generated Images do not represent the exact look and feel of the development. The Computer Generated Images do not represent the exact look and feel of the development. 5 THE LIVING SPACE Contemporary living at its very best, the apartments within 12 Elgin Avenue are finished to the highest specification. Light and spacious kitchens, bright and elegant bathrooms and stylish and modern open-plan living areas, make 12 Elgin Avenue apartments the ideal living solution.Features include engineered oak flooring to lounges and hallways, 80/20 wool carpets on heavy duty underlay to all bedrooms, porcelain tiles, and white gloss German kitchens, energy saving recessed lighting in the kitchen, bathrooms and lounges. 6 7 THE AREA Maida Vale is an affluent predominantly residential area, characterised by numerous large, late Victorian and Edwardian houses and blocks of mansion flats.In terms of housing supply the area is dominated by apartments, with many houses having been converted into flats. -

Rvs School Uniform Policies

RVS SCHOOL UNIFORM POLICIES An RVS school uniform is required for all students. Students must always, at minimum, meet the following uniform requirements, however are welcome to dress in a more formal uniform should they choose, i.e. wear the Full-Dress Uniform on Monday, Tuesday, Thursday or Friday. Please watch for emailed requests from the classroom teachers and check the online RVS Master Calendar for dates of special occasions (i.e. assemblies) requiring changes to the uniforms. STANDARD UNIFORM: The standard uniform is to be worn on Mondays, Tuesdays and Thursdays. FULL DRESS UNIFORM: The full-dress uniform must be worn every Wednesday as well as for the first day of school, concerts, assemblies, field trips, photo days and other special occasions as communicated from RVS. GYM STRIP: (Required For Grade 3 – 6 Students Only) The gym strip is used for Physical Education classes for Grades 3 - 6 only. It is to be kept at school in a cloth drawstring bag during the week and brought home regularly for laundering. SUMMER UNIFORM: (Optional) All students have the option to choose to wear Summer Uniform pieces from September to Thanksgiving and after Spring Break through June. Students are also welcome to wear dark dress sandals as part of the optional summer uniform. CASUAL UNIFORM FRIDAYS: (Optional) On Fridays, students have the option to choose from the items below. Note, the tracksuits and leggings must be worn with the RVS crested t-shirt or polo shirt. o Tots - Kindergarten: Crew neck sweatshirt, Polar Fleece, Jogging pant or Leggings. o Grade 1-6: Polar Fleece, Leggings or Tracksuit. -

Whiteleys Centre Queensway London W2 4YH PDF 6 MB

Item No. 1 CITY OF WESTMINSTER PLANNING Date Classification APPLICATIONS SUB For General Release COMMITTEE 8 October 2019 Report of Ward(s) involved Director of Place Shaping and Town Planning Lancaster Gate Subject of Report Whiteleys Centre, Queensway, London, W2 4YH Proposal Variation of Condition 1 of planning permission dated 19 November 2018 (RN: 18/04595/FULL), which itself varied Conditions 1, 15 and 16 and removal of Condition 49 of planning permission dated 1 November 2017 (RN: 16/12203/FULL), which varied Condition 1 and removed Condition 10 of planning permission dated 27 April 2016 (RN: 15/10072/FULL) for: Demolition of and redevelopment of building behind retained and refurbished facades to Queensway and Porchester Gardens facades to provide a mixed use development comprising three basement levels, ground floor and up to 10 upper floor levels, containing 103 to 129 residential units (Class C3), retail floorspace (Class A1 and A3) facing Queensway and arranged around a new retail arcade below re-provided central atrium and central retail courtyard, public car park, hotel (Class C1), cinema (Class D2) gym (Class D2), crèche (Class D1), with associated landscaping and public realm improvements, provision of 103 basement residential parking spaces, cycle parking and associated basement level plant and servicing provision. NAMELY, variation of Condition 1 to increase number of residential units from 129 to 153 units, including 14 affordable units; amendment to townhouses along Redan Place; amendment of residential unit mix; reduction in basement excavation depth with associated amendment to car and cycle parking and basement level plant, relocation of servicing bay to ground level and removal of public car park; revisions to hotel, cinema and gym floorspace, including increase in hotel room numbers to 111 and relocation of swimming pool to hotel; removal of crèche use; and replacement of windows to parts of the historic façade with double glazed windows. -

PONCE DE LEON MIDDLE IS a MANDATORY UNIFORM SCHOOL Each Student Is Expected to Wear the Official School Uniform

PONCE DE LEON MIDDLE IS A MANDATORY UNIFORM SCHOOL Each student is expected to wear the official school uniform. Tops (Shirts) • White or navy-blue polo‐style shirts (with collar) No striped shirts. Shirts must have the School Logo. • All clothing must be appropriately sized. • Shirts must not go below the student’s extended fingertips when their arms are placed at their side. • No colors other than white or navy blue are allowed at any time. • School polo shirts must be worn every day. Bottoms (Pants) • Navy blue or khaki pants. (Must be “docker” style.) No denim, jean‐like material, or spandex will be allowed. • Navy blue or khaki Shorts or Skirts. (Must be “docker” style.) No denim, jean‐like material, or spandex will be allowed. • No Skorts or Capris are allowed. • Shorts and Skirts length must be no more than one inch above the knee. • All clothing must be appropriately sized. Excessively tight or loose bottoms will not be allowed. • Undergarments CANNOT be visible at any time. • No colors other than navy blue or khaki are allowed. Jackets/Sweaters • Must be navy blue, gray, white or black. • Logos or writing across the front or back will not be allowed. Other than the School Logo. Miscellaneous • Students must wear closed‐toe shoes that cover the entire foot. • Sliders or any kind of slip-on type shoe is not acceptable. • Excessive jewelry or decorative clothing; including hats, headbands or head coverings (unless used for religious purposes) will not be permitted. • Clothing with inappropriate written messages, pictures or symbols which portray ideas that are inimical to the health, safety and welfare of students, e.g. -

Shops Aug 2012

1 SHOPS Shops Among London’s main attractions are the long streets full of shops, some of which are famous throughout the world. All of those listed here were visited during 2011. Our survey teams found that access to shops has improved considerably in recent years. In particular there are fewer split levels, more accessible toilets, and more BCF. However, few have textphone details on their website and there are still a small number with unexpected split levels. Importantly, attitudes have changed, and staff members are more often understanding of special needs than was the case ten years ago. In this chapter we have concentrated mainly on the Oxford Street/Regent Street area, as well as including famous shops like Harrods, Harvey Nichols, Peter Jones and Fortnum and Mason. We have also included a few shops on Kensington High Street, and around Victoria. We have only visited and described a tiny percentage of London’s shops, so please do not be limited by listings in this section. Nearly all the big shops we have described have accessible toilets. Access is generally good, although the majority of the big stores have central escalators. The lifts are less obvious and may even be slightly difficult to find. Signage is highly variable. Most big department stores have a store guide/listing near the main entrance, or at the bottom of escalators, but these do not normally take account of access issues. A few have printed plans of the layout of each floor (which may be downloadable from their website), but these aren’t always very clear or accurate. -

Middle School Uniform Policy

MIDDLE SCHOOL UNIFORM POLICY The School strongly encourages students to label all appropriate uniform items to aid the School in returning lost items. Students who are constantly out of uniform will be denied admission to class and are subject to suspension and disciplinary probation. • Parker Uniforms is the official uniform provider of our school uniforms. Culwell & Sons is an alternate source for boys’ uniforms. • Students are to wear the school uniform correctly throughout the school day. Formal Uniforms Every Wednesday (for Eucharist), and on other days throughout the year, students are required to be in formal uniforms. These include a blazer, a school tie (for the boys), long pants (for the boys), and a skirt (for the girls). On a day designated as a formal uniform day, students are required to be in formal uniform for the entire day. Applies to All Students White Shirt White oxford button-down; tucked in with waistband visible and appropriately sized with all but the top button buttoned. Collars of shirts must be visible at all times and not tucked down or under outerwear. Shirts may not be stained, drawn on, missing buttons, or torn. Undershirt Solid white crewneck without logos or printing; short-sleeved only under short-sleeved shirt. All undergarments should be white or skin color. Socks Solid white or navy, small logo acceptable (no Nike Elites or similar); sock must completely cover the ankle bone at all times (ankle socks not permitted). Navy Blazer Must be worn on all formal uniform days, including Eucharist, and other days as requested. Blazers should fit and be in good condition. -

Lower School Uniform Policy Overview

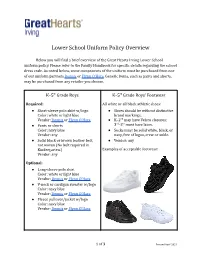

Lower School Uniform Policy Overview Below you will find a brief overview of the Great Hearts Irving Lower School uniform policy. Please refer to the Family Handbook for specific details regarding the school dress code. As noted below, some components of the uniform must be purchased from one of our uniform partners Dennis or Flynn O’Hara. Generic items, such as pants and shorts, may be purchased from any retailer you choose. K–5th Grade Boys K–5th Grade Boys’ Footwear Required: All white or all black athletic shoes: ● Short-sleeve polo shirt w/logo ● Shoes should be without distinctive Color: white or light blue brand markings. Vendor: Dennis or Flynn O’Hara ● K–2nd may have Velcro closures; rd th ● Pants or shorts 3 –5 must have laces. Color: navy blue ● Socks must be solid white, black, or Vendor: any navy, free of logos, crew or ankle. ● Solid black or brown leather belt, ● Vendor: any not woven (No belt required in Kindergarten.) Examples of acceptable footwear: Vendor: any Optional: ● Long-sleeve polo shirt Color: white or light blue Vendor: Dennis or Flynn O’Hara ● V-neck or cardigan sweater w/logo Color: navy blue Vendor: Dennis or Flynn O’Hara ● Fleece pullover/jacket w/logo Color: navy blue Vendor: Dennis or Flynn O’Hara 1 of 3 Revised April 2021 K–5th Grade Girls K–5th Grade Girls’ Footwear Choice 1: Option 1: Keds “School Days II” sneakers ● Short-sleeve polo shirt w/logo Option 2: Black or navy Mary Janes Color: white or light blue Option 3: All white or all black athletic Vendor: Dennis or Flynn O’Hara shoes: ● Pants or shorts Color: navy blue ● Shoes should be without distinctive Vendor: any brand markings. -

King's College, Cambridge

King’s College, Cambridge Annual Report 2014 Annual Report 2014 Contents The Provost 2 The Fellowship 5 Major Promotions, Appointments or Awards 18 Undergraduates at King’s 21 Graduates at King’s 26 Tutorial 36 Research 47 Library and Archives 51 Chapel 54 Choir 57 Bursary 62 Staff 65 Development 67 Appointments & Honours 72 Obituaries 77 Information for Non Resident Members 251 While this incremental work can be accomplished within the College’s The Provost maintenance budget, more major but highly desirable projects, like the refurbishment of the Gibbs staircases and the roof and services in Bodley’s will have to rely on support apart from that provided by the endowment. 2 I write this at the end of my first year at The new Tutorial team under Perveez Mody and Rosanna Omitowoju has 3 THE PROVOST King’s. I have now done everything once begun its work. There are now five personal Tutors as well as specialist and am about to attend Alumni Weekend Tutors, essentially reviving a system that was in place until a few years ago. reunion dinners for the second time. It has It is hoped that the new system will reduce the pastoral pressure on the been a most exciting learning experience THE PROVOST Directors of Studies, and provide more effective support for students. getting to know the College. While I have not had much time for my own research I In the Chapel we have said farewell to our Dean, Jeremy Morris. Jeremy have had the opportunity to learn about came to the College from Trinity Hall in 2010, and after only too short a others’ interests, and have been impressed time returns to his former College as its Master.