The Garment Industry's Best Kept Secret : Contuined Global

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rvs School Uniform Policies

RVS SCHOOL UNIFORM POLICIES An RVS school uniform is required for all students. Students must always, at minimum, meet the following uniform requirements, however are welcome to dress in a more formal uniform should they choose, i.e. wear the Full-Dress Uniform on Monday, Tuesday, Thursday or Friday. Please watch for emailed requests from the classroom teachers and check the online RVS Master Calendar for dates of special occasions (i.e. assemblies) requiring changes to the uniforms. STANDARD UNIFORM: The standard uniform is to be worn on Mondays, Tuesdays and Thursdays. FULL DRESS UNIFORM: The full-dress uniform must be worn every Wednesday as well as for the first day of school, concerts, assemblies, field trips, photo days and other special occasions as communicated from RVS. GYM STRIP: (Required For Grade 3 – 6 Students Only) The gym strip is used for Physical Education classes for Grades 3 - 6 only. It is to be kept at school in a cloth drawstring bag during the week and brought home regularly for laundering. SUMMER UNIFORM: (Optional) All students have the option to choose to wear Summer Uniform pieces from September to Thanksgiving and after Spring Break through June. Students are also welcome to wear dark dress sandals as part of the optional summer uniform. CASUAL UNIFORM FRIDAYS: (Optional) On Fridays, students have the option to choose from the items below. Note, the tracksuits and leggings must be worn with the RVS crested t-shirt or polo shirt. o Tots - Kindergarten: Crew neck sweatshirt, Polar Fleece, Jogging pant or Leggings. o Grade 1-6: Polar Fleece, Leggings or Tracksuit. -

PONCE DE LEON MIDDLE IS a MANDATORY UNIFORM SCHOOL Each Student Is Expected to Wear the Official School Uniform

PONCE DE LEON MIDDLE IS A MANDATORY UNIFORM SCHOOL Each student is expected to wear the official school uniform. Tops (Shirts) • White or navy-blue polo‐style shirts (with collar) No striped shirts. Shirts must have the School Logo. • All clothing must be appropriately sized. • Shirts must not go below the student’s extended fingertips when their arms are placed at their side. • No colors other than white or navy blue are allowed at any time. • School polo shirts must be worn every day. Bottoms (Pants) • Navy blue or khaki pants. (Must be “docker” style.) No denim, jean‐like material, or spandex will be allowed. • Navy blue or khaki Shorts or Skirts. (Must be “docker” style.) No denim, jean‐like material, or spandex will be allowed. • No Skorts or Capris are allowed. • Shorts and Skirts length must be no more than one inch above the knee. • All clothing must be appropriately sized. Excessively tight or loose bottoms will not be allowed. • Undergarments CANNOT be visible at any time. • No colors other than navy blue or khaki are allowed. Jackets/Sweaters • Must be navy blue, gray, white or black. • Logos or writing across the front or back will not be allowed. Other than the School Logo. Miscellaneous • Students must wear closed‐toe shoes that cover the entire foot. • Sliders or any kind of slip-on type shoe is not acceptable. • Excessive jewelry or decorative clothing; including hats, headbands or head coverings (unless used for religious purposes) will not be permitted. • Clothing with inappropriate written messages, pictures or symbols which portray ideas that are inimical to the health, safety and welfare of students, e.g. -

Middle School Uniform Policy

MIDDLE SCHOOL UNIFORM POLICY The School strongly encourages students to label all appropriate uniform items to aid the School in returning lost items. Students who are constantly out of uniform will be denied admission to class and are subject to suspension and disciplinary probation. • Parker Uniforms is the official uniform provider of our school uniforms. Culwell & Sons is an alternate source for boys’ uniforms. • Students are to wear the school uniform correctly throughout the school day. Formal Uniforms Every Wednesday (for Eucharist), and on other days throughout the year, students are required to be in formal uniforms. These include a blazer, a school tie (for the boys), long pants (for the boys), and a skirt (for the girls). On a day designated as a formal uniform day, students are required to be in formal uniform for the entire day. Applies to All Students White Shirt White oxford button-down; tucked in with waistband visible and appropriately sized with all but the top button buttoned. Collars of shirts must be visible at all times and not tucked down or under outerwear. Shirts may not be stained, drawn on, missing buttons, or torn. Undershirt Solid white crewneck without logos or printing; short-sleeved only under short-sleeved shirt. All undergarments should be white or skin color. Socks Solid white or navy, small logo acceptable (no Nike Elites or similar); sock must completely cover the ankle bone at all times (ankle socks not permitted). Navy Blazer Must be worn on all formal uniform days, including Eucharist, and other days as requested. Blazers should fit and be in good condition. -

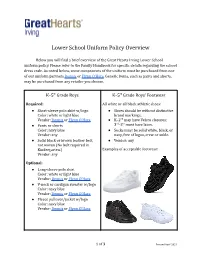

Lower School Uniform Policy Overview

Lower School Uniform Policy Overview Below you will find a brief overview of the Great Hearts Irving Lower School uniform policy. Please refer to the Family Handbook for specific details regarding the school dress code. As noted below, some components of the uniform must be purchased from one of our uniform partners Dennis or Flynn O’Hara. Generic items, such as pants and shorts, may be purchased from any retailer you choose. K–5th Grade Boys K–5th Grade Boys’ Footwear Required: All white or all black athletic shoes: ● Short-sleeve polo shirt w/logo ● Shoes should be without distinctive Color: white or light blue brand markings. Vendor: Dennis or Flynn O’Hara ● K–2nd may have Velcro closures; rd th ● Pants or shorts 3 –5 must have laces. Color: navy blue ● Socks must be solid white, black, or Vendor: any navy, free of logos, crew or ankle. ● Solid black or brown leather belt, ● Vendor: any not woven (No belt required in Kindergarten.) Examples of acceptable footwear: Vendor: any Optional: ● Long-sleeve polo shirt Color: white or light blue Vendor: Dennis or Flynn O’Hara ● V-neck or cardigan sweater w/logo Color: navy blue Vendor: Dennis or Flynn O’Hara ● Fleece pullover/jacket w/logo Color: navy blue Vendor: Dennis or Flynn O’Hara 1 of 3 Revised April 2021 K–5th Grade Girls K–5th Grade Girls’ Footwear Choice 1: Option 1: Keds “School Days II” sneakers ● Short-sleeve polo shirt w/logo Option 2: Black or navy Mary Janes Color: white or light blue Option 3: All white or all black athletic Vendor: Dennis or Flynn O’Hara shoes: ● Pants or shorts Color: navy blue ● Shoes should be without distinctive Vendor: any brand markings. -

2016-2017 Lower School Uniform Code

2016-2017 Lower School Uniform Code Students must be in full, smartly-presented uniform on entering Fifth- and sixth-grade students are required to wear either sweaters school buildings and must remain in full, smartly-presented uniform or blazers with their winter uniforms. Blazers for fifth- and sixth- until the end of the school day. Students on campus after the end of grade students are a uniform requirement for All-School and Lower the school day may be out of uniform or relax some uniform items School Masses (though not grade level Masses) during the entire in accordance with casual dress guidelines. Students will wear their school year. HSP sweaters (and blazers for fifth- and sixth-grade Dress uniform for All-School Masses as defined on the school students) are the only outerwear permitted in the classroom at all calendar throughout the school year, and on other days as an- grade levels. nounced. School uniforms are purchased through Parker School Uniforms Students are personally responsible for their own uniform and, while (formerly Buckhead Uniforms) or Sue Mills Uniforms, which we would request that parents and guardians monitor their student’s have both store fronts and online shopping options. In addition appearance before leaving the house each day, the student will be to this uniform code, copies of the school uniform requirements, held accountable for dirty, damaged, or incomplete uniforms. including specific colors and styles for uniforms, are available at Parker School Uniforms and Sue Mills Uniforms. They offer sales Students who are deemed inappropriately dressed will be asked to throughout the summer and school year. -

Uniform Policy

Proactive Dress Code Policy Central, East, & West The Pembroke Pines Charter Schools have a mandatory uniform dress code policy. We believe that students have the right to attend a safe and secure school where the focus is on academics. It is the intent of the school program that students be dressed and groomed in an appropriate manner that will not interfere with or distract from the school environment or disrupt the educational process. Clothing should follow the dress code in place for the Charter Schools. 1. All students must wear one of the approved uniform outfits. 2. Shirts (for students in grades K -5 ) must be tucked in at all times while on campus. 3. Uniform shirts must be navy blue, light blue, hunter green or white. All uniform shirts must have the school logo. Undershirts must be school shirt colors and must be solid with no markings or logos. 4. All clothing should fit properly and b e worn correctly. Revealing clothing or clothing that exposes the torso is not allowed. Denim leggings, jeggings are not allowed. Clothing that exposes the upper thigh including shorts that are rolled up/in are not allowed. Hemmed shorts that are not shorter than mid-thigh, (not shorter than middle finger length) including walking shorts, Bermuda shorts, and split skirts (culottes), are allowed. 5. Boys – school uniform bottom should be navy blue pants or shorts – no cargo pockets. All bottoms should be properly fitted at the waist. 6. Girls – school uniform navy blue pants, Capri’s, shorts, or skorts, or navy blue plaid skorts – no skirts, dresses, or jumpers. -

THE SCIS SCHOOL UNIFORM the SCIS School Uniform

THE SCIS SCHOOL UNIFORM The SCIS School Uniform SCIS students adhere to a dress code that we believe promotes Haircuts, hair dyes, jewelry, makeup, body art or other aspects of a sense of orderliness and school community, helps with campus personal appearance that are distracting to the learning process and field trip security, and reduces “fashion competition”. We are not allowed, interpretation of this is determined by divisional aim to have students wearing similar, if not necessarily identical, administration. outfits that engender a feeling of community and avoid clothes conscious social situations. There are occasionally “spirit” days on which students are not required to wear the school uniform. These may occur approxi- All students wear laced shoes or sturdy sandals. Athletic shoes mately once a month, usually in connection with a special holiday or sneakers are acceptable, but “flip-flops”, “thong” sandals, and or event, and will be announced by the school administration. other beach-type footwear are not appropriate for school. On those days, students are expected to wear shirts with sleeves Caps or hats in buildings are also inappropriate. It is preferred (no tank top or halter top shirts) and must look neat and pre- that winter outerwear be navy blue, grey or tan in color, and sentable. Students will normally wear the school uniform for field these garments should be removed when indoors. The use of trips, unless otherwise indicated on the permission form. light sweatshirts/hoodies (i.e. GAP or Abercrombie and Fitch sweatshirts) or sweaters that are not distributed by the uniform Students who do not have the proper school attire may be office are not acceptable during school hours. -

TERRA Environmental Research Institute Dress Code Policy

TERRA Environmental Research Institute Dress Code Policy Polos: White or Hunter Green Shirts (hunter green, navy blue or white) worn underneath the polo; must not extend beyond polo sleeve or below bottom of polo. Shirt must be tucked in. Bottoms: Navy Blue Pants must fit neatly and loosely. Pants must also be worn at the waist with a belt. Pants with loops and belt are required. No skinny-style pants or joggers are permitted. Athletic / nylon /denim / knitted / corduroy type pants are not permitted. Outerwear: Sweatshirts, sweaters, and jackets must not have hoodies and are required to be in compliance with uniform colors. Outerwear must be solid colors: navy blue, hunter green or white with the TERRA logo. They must be worn over the school uniform (Polo shirt underneath visible) and must display the TERRA logo in the upper left corner. Shoes: Only closed-toe-shoes are allowed. Spirit/Team/Club T-shirts: May be worn on Fridays as determined by the school administration. Announcements will be made. Please note that non-permissible clothing items/accessories include but are not limited to the following: • No brand names / designer polos showing logos. • No leggings, athletic wear, blue jeans/ pajama pants, etc. • No hats, bandanas, head scarves, or hoodies. • No written messages, pictures, or symbols related to drugs, smoking, alcohol, sex, profanity, gangs or any other negative message. • No backless shoes, cleats, Crocs, house slippers, or shoes with wheels are allowed in school grounds. • No trench coats. Students wearing any articles of clothing, jewelry, or hairstyles that may be construed as hazardous, distasteful or a distraction to the learning environment will not be permitted in the school. -

Cipc Publication

CIPC PUBLICATION 28 October 2013 Publication No. 201340 Notice No. 29 (AR DEREGISTRATIONS) Deregistration of Companies And Close Corporations. Deregistrasie Van Maatskappye en Beslote Koperasies. NOTICE IN TERMS OF SECTION 82 (3) (b) (ii) OF THE COMPANIES ACT, 2008, SECTION 26 OF THE CLOSE CORPORATION ACT,1984 AND REGULATION 40 (4) OF THE COMPANIES REGULATIONS 2011, THAT AFTER EXPIRATION OF 20 BUSINESS DAYS FROM THE DATE OF PUBLICATION OF THIS NOTICE, THE NAMES OF THE COMPANIES AND CLOSE CORPORATIONS MENTIONED IN B LIST HEREUNDER WILL, UNLESS CAUSE IS SHOWN TO THE CONTRARY, BE STRUCK OFF THE REGISTER AND THE REGISTRATION OF THE CORRESPONDING MOI OR FOUNDING STATEMENT CANCELLED. KENNISGEWING INGEVOLGE ARTIKEL 82 (3) (b) (ii) VAN DIE MAATSKAPPYWET,2008, ARTIKEL 26 VAN DIE BESLOTE KOPERASIES,1984 DAT NA AFLOOP VAN 20 BESIGHEIDSDAE VANAF PUBLIKASIE VAN HIERDIE KENNISGEWING, DIE NAME VAN DIE MAATSKAPPYE EN BESLOTE KOPERASIES IN LYS B HIERONDER GENOEM, VAN DIE REGISTER GESKRAP EN DIE BETROKKE AKTE OF STIGTINGSVERKLARING GEKANSELLEER SAL WORD, TENSY GRONDE DAARTEEN AANGEVOER WORD. -

School Uniform and Standards for Personal Appearance and Grooming As Authorized by State Law and the LPS Charter, Students Are Required to Wear Uniforms to School

2017-2018 Parent-Student Handbook excerpt School Uniform and Standards for Personal Appearance and Grooming As authorized by state law and the LPS charter, students are required to wear uniforms to school. Leadership Prep’s dress code is established to teach grooming and hygiene, to prevent disruption, and to minimize safety hazards. Students must come to school cleanly and neatly groomed, and wearing clothing that will not be a health or safety hazard to the student or others and that will not distract from the educational atmosphere of the school. Students are required to arrive in a proper school uniform every day. Parents must provide their student(s) with the required uniform, except in the case of educationally disadvantaged students as provided in the Texas Education Code. LPS may provide a uniform for economically disadvantaged students. A request for school assistance for purchasing uniforms must be made in writing to the Principal and include evidence of the inability to pay. Further details are available in the Principal’s office. A parent may choose for his or her student(s) to be exempted from the requirement of wearing a uniform if the parent provides a written statement that, as determined by the Board of Directors, states a bona fide religious or philosophical objection to the requirement. Uniform Information and Policy To maintain a consistent appearance among students, LPS has selected certain acceptable types of clothing which may be purchased through Academic Outfitters, Wal-Mart, Target, Old Navy, Land’s End, JC Penney, or a variety of other sources. Please see the Academic Outfitters information and pictures on our website to see approved styles even if you don’t purchase through them. -

Dress Codes and Uniforms. INSTI TUT ION National Association of Elementary School Principals, Alexandria , VA

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 465 198 EA 031 677 AUTHOR Lumsden, Linda; Miller, Gabriel TITLE Dress Codes and Uniforms. INSTI TUT ION National Association of Elementary School Principals, Alexandria , VA. SPONS AGENCY Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 5P * CONTRACT ED-99-CO-0011 AVAILABLE FROM National Association of Elementary School Principals, 1615 Duke St., Alexandria, VA 22314-3483 ($2.50 prepaid; quantity discounts). Tel: 800-386-2377 (Toll Free); Fax: 800-396-2377 (Toll Free); Web site: http://www.naesp.org. PUB TYPE Collected Works - Serials (022) -- ERIC Publications (071) JOURNAL CIT Research Roundup; v18 n4 Sum 2002 EDRS PRICE MFOI/PCOI Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Administrator Guides; Court Litigation; *Dress Codes; Educational Environment; Elementary Secondary Education; School Policy; *School Uniforms; Student Behavior ABSTRACT Students do not always make choices that adults agree with in their choice of school dress. Dress-code issues are explored in this Research Roundup, and guidance is offered to principals seeking to maintain a positive school climate. In "DO School Uniforms Fit?" Kerry White discusses arguments for and against school uniforms and summarizes the state of research in this area. Deborah Elder evaluates the implementation and effects of a mandatory uniform policy at two middle schools in IIEvaluation of School Uniform Policy at John Adams and Truman Middle Schools for Albuquerque Public Schools." Todd DeMitchell and colleagues, in "Dress Codes in the Public Schools: Principals, Policies, and Precepts," report on principals' views on dress codes and look at sample policies. In IISchool Uniforms: Can Voluntary Programs Work? Experimenting in an At-Risk School," Richard Dougherty describes the adoption of a voluntary uniform policy at a middle school. -

Student Planner – School Uniform Information

School Uniform A high standard of personal appearance is expected of all students and anyone arriving at school in non-uniform clothing may expect to serve a detention. • Exaggerated hair styles are not acceptable. These include: shaved/very closely cut hair (shorter than a number 2 cut); multi- coloured hair; tramlines; extreme wedges; unnatural hair colours. • T-shirt type blouses or sweatshirts may not be worn as uniform. • Large pullovers/sweatshirts/hoodies without a zip must not be worn to school as an alternative to coats/jackets. Coats and other outdoor clothing may not be worn in school. • Baseball caps must not be worn on the campus. • Corduroy, leather and denim may not be worn as uniform. • Make-up is not permitted in Years 7, 8 and 9; subtle make-up is allowed in Years 10 and 11. • Jewellery: just one small plain gold or silver stud may be worn in each ear. This rule applies to both boys and girls. No other jewellery may be worn. • Belts must be plain and dark in colour. They must fit through the belt loops on your trousers/skirt. • Beards and moustaches are not allowed. Girls • Trousers and skirts: Black plain knee length skirts or trousers must be worn. Students cannot wear trousers that are leggings or jeans style, or have fashion accessories such as decorative zips. Trousers must not be too short and must reach to the shoe/sock/ankle. • White blouse (shirt style, plain collar) with House Tie. • Huntington School jumper with logo (navy for Years 7-10; black for Year 11).