A 50-State Roadmap for Curbing Our Dependence on Petroleum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Support Document for Revised

Support Document for the Revised National Priorities List Final Rule - July 2000 State, Tribal, and Site Identification Center Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Washington, DC 20460 ABSTRACT Pursuant to Section 105(a)(8)(B) of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 (CERCLA) as amended by the Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act of 1986 (SARA), the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) periodically adds hazardous waste sites to the National Priorities List (NPL). Prior to actually listing a site, EPA proposes the site in the Federal Register and solicits public comments. This document provides responses to public comments received on one site proposed on January 19, 1999 (64 FR 2950), one site proposed on April 23, 1999 (64 FR 19968), one site proposed on July 22, 1999 (64 FR 39886), and two sites proposed on February 4, 2000 (65 FR 5468). All of the sites are added to the NPL based on an evaluation under the HRS. These sites are being added to the NPL in a final rule published in the Federal Register in July 2000. ii CONTENTS Executive Summary ............................................................ v Introduction ................................................................... vii Background of the NPL ....................................................... vii Development of the NPL ......................................................viii Hazard Ranking System........................................................ix Other -

Serum Anion Gap: Its Uses and Limitations in Clinical Medicine

In-Depth Review Serum Anion Gap: Its Uses and Limitations in Clinical Medicine Jeffrey A. Kraut* and Nicolaos E. Madias† *Medical and Research Services VHAGLA Healthcare System, UCLA Membrane Biology Laboratory, and Division of Nephrology VHAGLA Healthcare System and David Geffen School of Medicine, Los Angeles, California; and †Department of Medicine, Division of Nephrology, Caritas St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center, and Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts The serum anion gap, calculated from the electrolytes measured in the chemical laboratory, is defined as the sum of serum chloride and bicarbonate concentrations subtracted from the serum sodium concentration. This entity is used in the detection and analysis of acid-base disorders, assessment of quality control in the chemical laboratory, and detection of such disorders as multiple myeloma, bromide intoxication, and lithium intoxication. The normal value can vary widely, reflecting both differences in the methods that are used to measure its constituents and substantial interindividual variability. Low values most commonly indicate laboratory error or hypoalbuminemia but can denote the presence of a paraproteinemia or intoxi- cation with lithium, bromide, or iodide. Elevated values most commonly indicate metabolic acidosis but can reflect laboratory error, metabolic alkalosis, hyperphosphatemia, or paraproteinemia. Metabolic acidosis can be divided into high anion and normal anion gap varieties, which can be present alone or concurrently. A presumed 1:1 stoichiometry between change in the ؊ ⌬ ⌬ serum anion gap ( AG) and change in the serum bicarbonate concentration ( HCO3 ) has been used to uncover the concurrence of mixed metabolic acid-base disorders in patients with high anion gap acidosis. -

Detailed Topic Index of Sure Success MAGIC 11Th Edn. Please Download, Save As PDF on Your Phones/Laptops/Computers OR Still

Sure Success MAGIC 11th Edition: 'TOPIC INDEX' by Dr B Ramgopal Detailed Topic Index of Sure Success MAGIC 11th edn. Please download, save as PDF on your phones/laptops/computers OR still better print it and insert 2-3 extra blank sheets in between the chapters so that you can just spiral bind it later and use it to insert any extra topics/ matter which you feel is relevant. Thus it would add more value and help in revision also. All the Best Dr Ramgopal Sure Success MAGIC 11th Edition: 'TOPIC INDEX' by Dr B Ramgopal EMBRYOLOGY GROWTH FACTORS AND GENES IN EMBRYOGENESIS 1 SPERMATOGENESIS 1 Spermatozoa (Sperm) 1 OOGENESIS 2 PRE-EMBRYONIC PERIOD 3 Fertilization and Implantation (0–7 Days; 1st Week) 3 2nd Week of Development 4 EMBRYONIC PERIOD (3–8 WEEKS) 4 Stage of Trilaminar Germ Disc—3rd Week 4 Ectoderm 4 Neurulation 4 Mesoderm 4 TIMELINE OF EVENTS AFTER FERTILIZATION 5 GERM LAYER DERIVATIVES 6 BRANCHIAL (PHARYNGEAL) APPARATUS 8 Branchial Arch Derivatives 8 Branchial Cleft Derivatives 8 Branchial Pouch Derivatives 8 GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT 9 Derivatives of the ‘Gut’ 9 Liver development 9` Pancreas development 9 CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM 9 Heart tube embryological derivatives 9 Aortic Arches and their Derivatives (Fig. 1.5) 9 More Important Points about CVS Embryology 10 Fetal-Postnatal Derivatives 10 URINARY SYSTEM 11 Kidney Embryology 11 Urinary bladder embryology 11 Development of urethra 11 GENITAL HOMOLOGUES IN MALE AND FEMALE 11 DESCENT OF TESTIS , Cryptorchidism 12 CNS EMBRYOLOGY 12 Parts of Developing Brain and their Adult Derivatives -

Environmental Health Criteria 166 METHYL BROMIDE

Environmental Health Criteria 166 METHYL BROMIDE Please note that the layout and pagination of this web version are not identical with the printed version. Methyl Bromide (EHC 166, 1995) INTERNATIONAL PROGRAMME ON CHEMICAL SAFETY ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH CRITERIA 166 METHYL BROMIDE This report contains the collective views of an international group of experts and does not necessarily represent the decisions or the stated policy of the United Nations Environment Programme, the International Labour Organisation, or the World Health Organization. First draft prepared by Dr. R.F. Hertel and Dr. T. Kielhorn. Fraunhofer Institute of Toxicology and Aerosol Research, Hanover, Germany Published under the joint sponsorship of the United Nations Environment Programme, the International Labour Organisation, and the World Health Organization World Health Orgnization Geneva, 1995 The International Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS) is a joint venture of the United Nations Environment Programme, the International Labour Organisation, and the World Health Organization. The main objective of the IPCS is to carry out and disseminate evaluations of the effects of chemicals on human health and the quality of the environment. Supporting activities include the development of epidemiological, experimental laboratory, and risk-assessment methods that could produce internationally comparable results, and the development of manpower in the field of toxicology. Other activities carried out by the IPCS include the development of know-how for coping with chemical accidents, -

Health Hazard Evaluation Report 77-73-610

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION, AND WELFARE CENTER FOR DISEASE CONTROL NATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR OCCUPATIONAL SAFETY AND HEALTH CINCINNATI, OHIO 45226 HEALTH HAZARD EVALUATION DETERMINATION REPORT HE 77-73-610 VELSICOL CHEMICAL CORPORATION 500 NORTH BANKSON STREET ST. LOUIS, MICHIGAN 48880 August 1979 I. TOXICITY DETERMINATION The fo 11 owing determi nations have been made based on envi ronmenta1 air samples collected on June 6-8, 1977, medical examination of employees on October 17-22, 1977, evaluation of ventilation systems and work practices, and available toxicity information. The accompanying medical report (following this Toxicity Determination Report} produced for NIOSH under contract by Cook County Hospital gives good evidence that workers at the St. Louis, Michigan Velsicol Plant showed a high incidence of acneifor,n skin lesions quite possibly caused by occupational exposure to halogenated chemicals. Additional evidence is presented that some employees may have had adverse health effects upon either their nervous, cardiovascular, hepatic, immune or respiratory systems. Medical recommendations are included in the following medical report and in Section VI of this report. Employee exposures to ethylene dichloride (EDC) in the Fine Chemicals and HBCD Department exceeded the NIOSH recommend standard. In the Industrial Bromides Department, employee exposures to carbon tetrachloride exceeded the NIOSH recommended standard. In the Tetrabromophthalic Anhydride Department; employees may be overexposed to sulfur dioxide during the opening of the reactor hatch for raw material addition. Employees were also exposed to a variety of other chemicals for which neither evaluation criteria nor air sampling/analytical methods existed, or whose air samples were below the analytical limits of detection. -

Download Report (PDF)

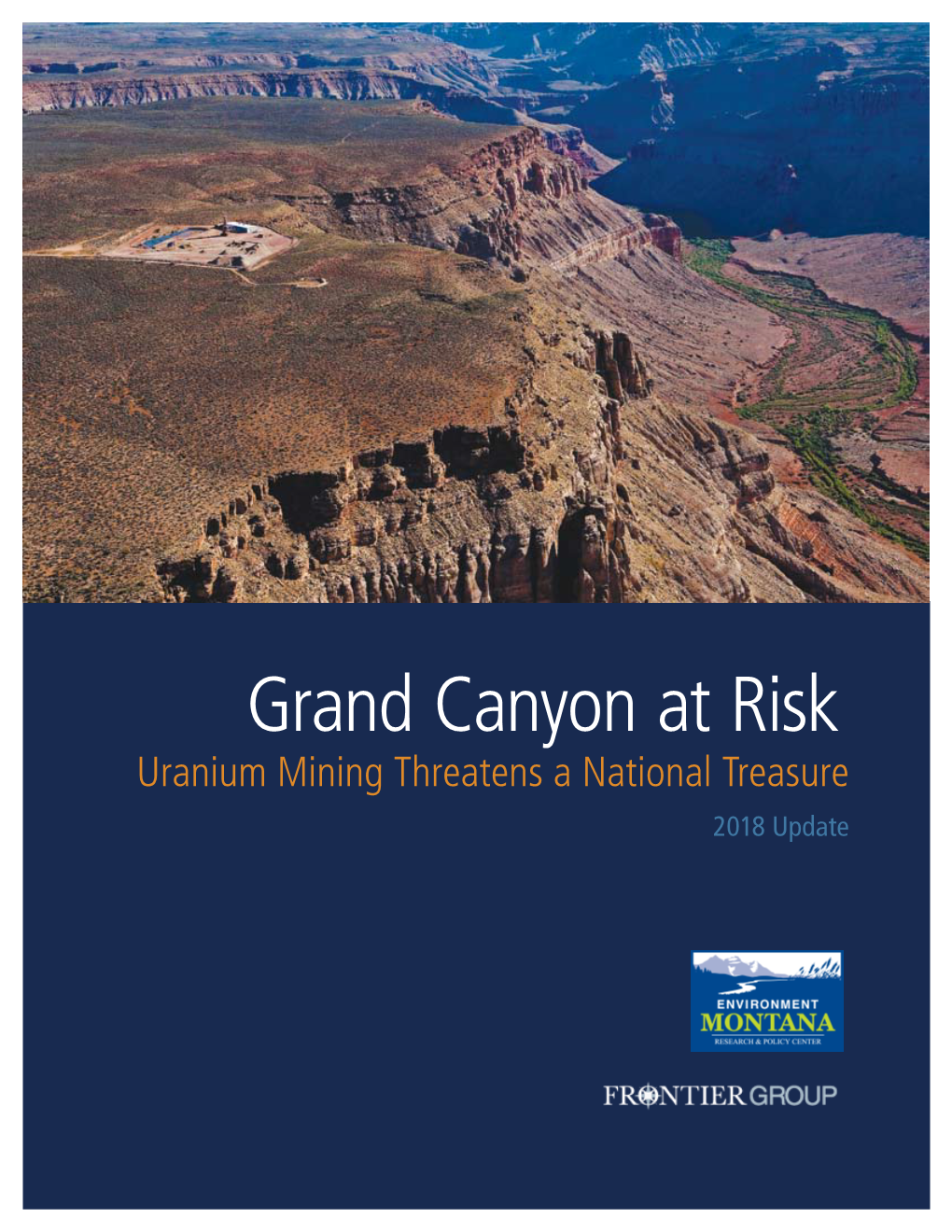

Grand Canyon at Risk Uranium Mining Threatens a National Treasure 2018 Update Grand Canyon at Risk Uranium Mining Threatens a National Treasure Abigail Bradford, Frontier Group Christy Leavitt and Steve Blackledge, Environment America Research & Policy Center 2018 Update Acknowledgments The authors wish to thank Kelly Burke of Wildlands Network; Miriam Wasser, freelance environmental journalist; and Roger Clark of the Grand Canyon Trust for their insightful comments on drafts of this report. Thanks also to Tony Dutzik, Elizabeth Berg and Gideon Weissman of Frontier Group, and Bret Fanshaw of Environment America Research & Policy Center for providing editorial support. This is an updated version of a report originally published in 2011. We thank Rob Kerth, Jordan Schneider and Elizabeth Ridlington of Frontier Group and Anna Aurilio of Environment America Research & Policy Center for their efforts as authors of the original report, as well as all those who contributed to the original report as reviewers or funders. The authors bear responsibility for any factual errors. The recommendations are those of Environment America Research & Policy Center. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders or those who provided review. © 2018 Environment America Research & Policy Center. Some Rights Reserved. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 3.0 Unported License. To view the terms of this license, visit creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0. Environment America Research & Policy Center is a 501(c)(3) organization. We are dedicated to protecting our air, water and open spaces. -

Medical Compend for Commanding Officers of Naval Vessels to Which

C F N AVAL VESSELS 1941 MEDICAL COMPEND For Commanding Officers of Naval Vessels to Which no Member of the Medical Department of the United States Navy Is Attached To accompany -Srfedici««<^Sox PUBLISHED BY THE BUREAU OF MEDICINE AND SURGERY UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF THE SECRETARY OF THE NAVY UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1941 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. - -- -- - - - Price 60 cents Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, Navy Department, Washington , D. C., July i, 1911. This Medical Compend for commanding officers of naval vessels to which no member of the Medical Department of the United States Navy is attached, is published for their aid in the knowledge and use of the contents of the Medicine Box, United States Navy, as well as to be a general guide in the preservation of the health of the per- sonnel under their command. Ross T. McIntire, General United States . Surgeon , Navy CONTENTS Page Chapter I. Introduction 1 Contents of medicine boxes 3 The medicine box 3 The supplemental medicine box 4 The medical boat box 5 Directions for the use of medical supplies 6 Chapter II. First aid 10 Chapter III. Special diseases 32 Chapter IV. Venereal diseases and prophylaxis 61 Chapter V. Hospitalization 67 Chapter VI. Deaths 70 Chapter VII. Personal hygiene 76 Chapter VIII. Preventive medicine 78 Chapter IX. Quarantine, disinfection, bills of health 83 Glossary 111 Index - - 115 Chapter I MEDICAL SUPPLIES Introduction This Medical Compend, which accompanies the medicine box, is published primarily for the use of commanding officers of naval vessels to which no representative of the medical department is attached. -

Intentional Versus Unintentional Child Toxicity at National Center of Environmental and Clinical Research of Toxicology (Nectr)

INTENTIONAL VERSUS UNINTENTIONAL CHILD TOXICITY AT NATIONAL CENTER OF ENVIRONMENTAL AND CLINICAL RESEARCH OF TOXICOLOGY (NECTR) Thesis Submitted for partial fulfillment of Master Degree (M.Sc.) in FORENSIC MEDICINE & CLINICAL TOXICOLOGY By RANIA MOHSEN ABDEL RAHEEM (M.B., B.CH.) Demonstrator of Forensic Medicine and Clinical Toxicology Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University Under Supervision of PROF. DR. DINA ALI SHOKRY Professor and Head of Forensic Medicine & Clinical Toxicology Department Faculty of Medicine – Cairo University PROF. DR. HODA ABD ELMAGIED EL GHAMRY Professor of Forensic Medicine & Clinical Toxicology Faculty of Medicine – Cairo University DR. MARWA ISSAK MOHAMED Lecturer of Forensic Medicine & Clinical Toxicology Faculty of Medicine – Cairo University Faculty of Medicine Cairo University 2018 ﺑﺴﻢ اﷲ اﻟﺮﺣﻤﻦ اﻟﺮﺣﻴﻢ II ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First and foremost, all praises to ALLAH, who gave me the strength to accomplish this achievement and gifted me with people who tried to help all-through. It is a great honor to me to express my deepest gratitude to Prof. Dr. Dina Ali Shokry, Professor and Head of Forensic Medicine and Clinical Toxicology Department, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University, for her unlimited support, valuable guidance and sincere supervision that were the most driving forces in the initiation and progress of this work. She performed much effort and consumed much of her time in guiding me through this thesis. No words can fulfill my infinite thanks and appreciation to Prof. Dr. Hoda Abd Elmagied El Ghamry, Professor of Forensic Medicine and Clinical Toxicology, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University, for her continuous encouragement, meticulous supervision and great-unlimited help through this work. -

2015 ACMT Annual Scientific Meeting, March 27–29, 2015 Clearwater Beach, FL

J. Med. Toxicol. DOI 10.1007/s13181-014-0458-4 ANNUAL MEETING ABSTRACTS 2015 ACMT Annual Scientific Meeting, March 27–29, 2015 Clearwater Beach, FL 1. Efficacy of Trypsin in Treating Coral Snake Envenomation in the 2. Lipid Emulsion Rapidly Activates Insulin Signaling Both Alone Porcine Model and to Combat Toxicity During Bupivacaine-Induced Sensitization of IRS1 Parker-Cote JL, O’Rourke D, Brewer KL, Lertpiriyapong K, Girard J, Bush SP, Miller SN, Punja M, Meggs WJ Fettiplace MR, Kowal K, Young A, Ripper R, Lis K, Weinberg G Brody School of Medicine at Eastern Carolina University, Greenville, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA NC, USA Background: Recent publications have identified that local anesthetics Background: Though current definitive treatment for Micrurus fulvius uncouple insulinergic signaling by inhibitiing pi3k/Akt and lipid emul- fulvius envenomation is antivenin, this horse serum treatment carries sion activates Akt/GSK-3β following ischemia–reperfusion. Further- risks, and the antivenin for M. fulvius (Eastern coral snake) envenomation more, while it is clear that lipid emulsion exerts a cardiotonic effect, it is no longer in production. Therefore, investigation in alternative treat- is unclear through what pathway this effect functions. ments for M. fulvius envenomation is warranted. Hypothesis: We hypothesized that bupivacaine uncouples insulinergic Research Question: The objective of this study is to assess the efficacy signaling which sensitizes the heart to insulinergic signaling during of trypsin, a protease, in an in vivo porcine model by the local injection of recovery (via feedback to IRS1) and lipid emulsion activates insulinergic trypsin after M. fulvius venom injection. -

Green Synthetic Fuels: Renewable Routes for the Conversion of Non-Fossil Feedstocks Into Gaseous Fuels and Their End Uses

energies Review Green Synthetic Fuels: Renewable Routes for the Conversion of Non-Fossil Feedstocks into Gaseous Fuels and Their End Uses Elena Rozzi 1,2,*, Francesco Demetrio Minuto 1,2 , Andrea Lanzini 1,2 and Pierluigi Leone 1,2 1 Department of Energy, Politecnico di Torino, Corso Duca degli Abruzzi 24, 10129 Torino, Italy; [email protected] (F.D.M.); [email protected] (A.L.); [email protected] (P.L.) 2 Energy Center Lab, Politecnico di Torino, Corso Duca degli Abruzzi 24, 10129 Torino, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 6 December 2019; Accepted: 10 January 2020; Published: 15 January 2020 Abstract: Innovative renewable routes are potentially able to sustain the transition to a decarbonized energy economy. Green synthetic fuels, including hydrogen and natural gas, are considered viable alternatives to fossil fuels. Indeed, they play a fundamental role in those sectors that are difficult to electrify (e.g., road mobility or high-heat industrial processes), are capable of mitigating problems related to flexibility and instantaneous balance of the electric grid, are suitable for large-size and long-term storage and can be transported through the gas network. This article is an overview of the overall supply chain, including production, transport, storage and end uses. Available fuel conversion technologies use renewable energy for the catalytic conversion of non-fossil feedstocks into hydrogen and syngas. We will show how relevant technologies involve thermochemical, electrochemical and photochemical processes. The syngas quality can be improved by catalytic CO and CO2 methanation reactions for the generation of synthetic natural gas. Finally, the produced gaseous fuels could follow several pathways for transport and lead to different final uses. -

Methvl Bromide

INTERNATIONAL PROGRAMME ON CHEMICAL SAFETY Environmental Health Criteria 166 Methvl Bromide I R :ndei the joint sponsorship of the United Nations Environment Programme, teoationaI Labour Organisation, and the World Health Organization THE ENVlRONMrtsr(At HEAL')-) ('RITEFIIA 3611108 Acetorritrile (No 154 19931 Dixie irotolo,nrys (No 74 1987 Acro)ejn (No. 127, 1991) 1,2 Dch oroetrano (No 62 987( Acrylamide (No. 49 1985) 24 D chlorophenoxyacer c acid (24-0) fNo 29. Acrylonitrile (No 28 1983) 1984) Aged population, principles for eva(uat1ng the 2.4-Dichlorophenoxyacet c acid envroninc'nilal effects of chemicals (No. 144, 1992) aspects (No 84 1989) Aldicarb (No 121 1991( 1.30 chloropropene, 1 2 dichloro1 ropane at cI Aidriri and dieldrin (No 91 '989) mixtures (No 146. 1993) A(tethrins (No 87, 1989) Dicbtoraos (No 79 1988) Amitrole (No 158, 1994) Diethylhexyl phthalato (Nc 131 1902) Ammonia (No 54 1986) Dimethoste (No. 90, 1989) Arsenic (No 18 19i31( Dimethy)forrrarn dx (No 114 1901) Asbestos and ether natural m neral I bins O methyl sulfate (No 48 1985) (No 53, 1986) Diseases of suspectc-d chemical i'tio Igy iii) Bar urn (No 107 1990) her preventon pr nciplev Of s',,,1 I ', 011 Benomyt (No 148. 1993i (No 72, 1987) Benzene (No 150 1993) Di1hiocarbamatc pest rides, rthylenethiore.i and Beryllium (No 106. 1990) popyleneth,ourea a genlerar irntroductioii Bloinarkers and 'isk ansecsrnrnt c oor r pts (t'o 78. 1968) and principles (No 155. 1903) S c1romagnet r i e)ds IN , 137 00, Biotoxios aquatic (mar ire a rd freshwater) E'rdos bin No 409511 (No 37 1984) E - dim iNc 130 1 8mm rated diphenylethern (No 162 1 9"4i 5' 'vcnncntal ep.ci'i Butano3 four isomers No 05 l87 ,ioJks n (Nc 7 i I 11.1' Cadm irn (No 134 1992) EplcI on_li', drin (No 33 1984) Cadm urn - ens ronmerital aspects No 135, 1992) Etnye.e oxdr (No 55 r9h5( Camprechler (No 45, 1984) Extremel , l ow freqiierrr y EL - i Is N, Carbarnale pestic,den a general rtrodiii trcil 1 7au) (No 64 1986) Clot ii it' ill (No ' 33 '902, Carbaryl (Nc. -

LTC DELUXE SPA KIT-BROMINE 2X1CS (X) - Leisure Time Enzyme

MATERIAL SAFETY DATA SHEET FOR ANY EMERGENCY, 24 HOURS / 7 DAYS, CALL: 1-800-654-6911 (OUTSIDE USA: 1-423-780-2970) FOR ALL TRANSPORTATION ACCIDENTS, CALL CHEMTREC®: 1-800-424-9300 (OUTSIDE USA: 1-703-527-3887) FOR ALL MSDS QUESTIONS & REQUESTS, CALL: 1-800-511-MSDS (OUTSIDE USA: 1-423-780-2347) PRODUCT NAME: LTC DELUXE SPA KIT-BROMINE 2X1CS (X) - Leisure Time Enzyme 1. PRODUCT AND COMPANY IDENTIFICATION REVISION DATE: 05/05/2011 Advantis Technologies SUPERCEDES: 06/12/2009 1400 Bluegrass Lakes Parkway Alpharetta, GA 30004 MSDS Number: 000000012568 United States of America SYNONYMS: CHEMICAL FAMILY: None DESCRIPTION / USE None established FORMULA: None established 2. HAZARDS IDENTIFICATION OSHA Hazard This material is not hazardous under the criteria of the Federal OSHA Hazard Classification: Communication Standard 29CFR 1910.1200. Routes of Entry: This product will not exert a significant adverse effect to health from any route of exposure. Chemical Interactions: None known. Medical Conditions Aggravated: None known. Human Threshold Response Data Odor Threshold Not established for product. Irritation Threshold Not established for product. LTC DELUXE SPA KIT-BROMINE 2X1CS (X) - Leisure Time Enzyme REVISION DATE: 05/05/2011 Page 1 of 163 MATERIAL SAFETY DATA SHEET Hazardous Materials Identification System / National Fire Protection Association Classifications Hazard Ratings : Health Flammability Physical / Instability PPI / Special hazard. HMIS 0 0 0 NFPA 0 0 0 Immediate (Acute) Health Effects Inhalation Toxicity: Not expected to be toxic by inhalation. Not expected to cause irritation. Skin Toxicity: Not expected to cause irritation. Not expected to be toxic from dermal contact. Eye Toxicity: Not expected to be irritating.