Download the Full Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conference of Central and East European Countries on Fighting Corruption

CONFERENCE OF CENTRAL AND EAST EUROPEAN COUNTRIES ON FIGHTING CORRUPTION International Co-operation: Its Role in Preventing and Combating Corruption and in the Creation of Regional Strategies Bucharest, March 30-31st UN Global Programme against Corruption Programme Manager: Dr. Petter Langseth International Cooperation Dr. Petter Langseth Its Role in Preventing and Combating Corruption and in the Creation of Regional Strategies SUMMARY1 According to CICP’s Global Programme against Corruption the purpose of a national anti-corruption programme is to:(i) increase the risk and cost of being corrupt and (ii) build integrity that changes the rules of the game and the behaviour of the players and (iii) eventually ensure the rule of law. Among the few success stories, Hong Kong, should have taught us that it takes time and considerable effort to curb corruption in a systemic corrupt environment. After more than 25 years Hong Kong is spending US$ 90 million (1998) per year and employed 1300 staff who conducted 2780 training sessions for the private and public sector. This is probably more than what all 50 African countries spent fighting corruption in 1999.2 Taking into account the increasing number of international instruments dealing with corruption, the workshop will be aimed at promoting co-ordinated efforts for the development of joint strategies for implementation of international instrument and best prevention practices at the international, national and municipal level. The anti-corruption strategy advocated in this paper rests on four pillars: (a) economic development; (b) democratic reform; (c) a strong civil society with access to information and a mandate to oversee the state; and (d) the presence of rule of law. -

The Cabinet Handbook

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA THE CABINET HANDBOOK Cabinet Secretariat Office of the President www.cabinetsecretariat.go.ug December 2008 FOREWORD I am pleased to introduce the Cabinet Handbook which provides clear and comprehensive policy management guidelines for the Cabinet and other arms of Government involved in the policy management process. Cabinet is the highest policy making organ of government and is therefore responsible for policy development and its successful implementation. Cabinet collectively, and Ministers individually, have a primary duty to ensure that government policy best serves the public interest. This Cabinet Handbook outlines the principles by which Cabinet operates. It also sets out the procedures laid down to facilitate Cabinet’s realization of its central role of determining government policy and supporting ministers in meeting their individual and collective responsibilities, facilitating coordinated and strategic policy development. In the recent past, my government has made major contributions in the documentation and improvement of processes and procedures that support decision making at all levels of government. In conformity to our principle of transforming government processes and achieving greater transparency, and effectiveness in our management of policy; my government has focused its attention on introducing best practices in the processes and procedures that support decision making at all levels of Government. This Cabinet Handbook is primarily intended for Cabinet Ministers and Ministers of State. However, it must be read by all officers that are in various ways associated with the policy process, so that they are guided to make a better contribution to Cabinet's efficient functioning. The Secretary to Cabinet and the Cabinet Secretariat are available to offer advice and assistance. -

Uganda's Constitution of 1995 with Amendments Through 2017

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:53 constituteproject.org Uganda's Constitution of 1995 with Amendments through 2017 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:53 Table of contents Preamble . 14 NATIONAL OBJECTIVES AND DIRECTIVE PRINCIPLES OF STATE POLICY . 14 General . 14 I. Implementation of objectives . 14 Political Objectives . 14 II. Democratic principles . 14 III. National unity and stability . 15 IV. National sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity . 15 Protection and Promotion of Fundamental and other Human Rights and Freedoms . 15 V. Fundamental and other human rights and freedoms . 15 VI. Gender balance and fair representation of marginalised groups . 15 VII. Protection of the aged . 16 VIII. Provision of adequate resources for organs of government . 16 IX. The right to development . 16 X. Role of the people in development . 16 XI. Role of the State in development . 16 XII. Balanced and equitable development . 16 XIII. Protection of natural resources . 16 Social and Economic Objectives . 17 XIV. General social and economic objectives . 17 XV. Recognition of role of women in society . 17 XVI. Recognition of the dignity of persons with disabilities . 17 XVII. Recreation and sports . 17 XVIII. Educational objectives . 17 XIX. Protection of the family . 17 XX. Medical services . 17 XXI. Clean and safe water . 17 XXII. Food security and nutrition . 18 XXIII. Natural disasters . 18 Cultural Objectives . 18 XXIV. Cultural objectives . 18 XXV. Preservation of public property and heritage . 18 Accountability . 18 XXVI. Accountability . 18 The Environment . -

Elite Strategies and Contested Dominance in Kampala

ESID Working Paper No. 146 Carrot, stick and statute: Elite strategies and contested dominance in Kampala Nansozi K. Muwanga1, Paul I. Mukwaya2 and Tom Goodfellow3 June 2020 1 Department of Political Science and Public Administration, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda. Email correspondence: [email protected] 2 Department of Geography, Geo-informatics and Climatic Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda. Email correspondence: [email protected]. 3 Department of Urban Studies and Planning, University of Sheffield, UK Email correspondence: [email protected] ISBN: 978-1-912593-56-9 email: [email protected] Effective States and Inclusive Development Research Centre (ESID) Global Development Institute, School of Environment, Education and Development, The University of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PL, UK www.effective-states.org Carrot, stick and statute: Elite strategies and contested dominance in Kampala. Abstract Although Yoweri Museveni’s National Resistance Movement (NRM) has dominated Uganda’s political scene for over three decades, the capital Kampala refuses to submit to the NRM’s grip. As opposition activism in the city has become increasingly explosive, the ruling elite has developed a widening range of strategies to try and win urban support and constrain opposition. In this paper, we subject the NRM’s strategies over the decade 2010-2020 to close scrutiny. We explore elite strategies pursued both from the ‘top down’, through legal and administrative manoeuvres and a ramping up of violent coercion, and from the ‘bottom up’, through attempts to build support among urban youth and infiltrate organisations in the urban informal transport sector. Although this evolving suite of strategies and tactics has met with some success in specific places and times, opposition has constantly resurfaced. -

University Lecturers and Students Could Help in Community Education About SARS-Cov-2 Infection in Uganda

HIS0010.1177/1178632920944167Health Services InsightsEchoru et al 944167research-article2020 Health Services Insights University Lecturers and Students Could Help in Volume 13: 1–7 © The Author(s) 2020 Community Education About SARS-CoV-2 Infection Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions in Uganda DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/1178632920944167 10.1177/1178632920944167 Isaac Echoru1 , Keneth Iceland Kasozi2 , Ibe Michael Usman3 , Irene Mukenya Mutuku1, Robinson Ssebuufu4 , Patricia Decanar Ajambo4, Fred Ssempijja3, Regan Mujinya3 , Kevin Matama5, Grace Henry Musoke6 , Emmanuel Tiyo Ayikobua7 , Herbert Izo Ninsiima1, Samuel Sunday Dare1,2, Ejike Daniel Eze1,2, Edmund Eriya Bukenya1, Grace Keyune Nambatya8, Ewan MacLeod2 and Susan Christina Welburn2,9 1School of Medicine, Kabale University, Kabale, Uganda. 2Infection Medicine, Deanery of Biomedical Sciences, and College of Medicine & Veterinary Medicine, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK. 3Faculty of Biomedical Sciences, Kampala International University Western, Bushenyi, Uganda. 4Faculty of Clinical Medicine and Dentistry, Kampala International University Teaching Hospital, Bushenyi, Uganda. 5School of Pharmacy, Kampala International University Western Campus, Bushenyi, Uganda. 6Faculty of Science and Technology, Cavendish University, Kampala, Uganda. 7School of Health Sciences, Soroti University, Soroti, Uganda. 8Directorate of Research, Natural Chemotherapeutics Research Institute, Ministry of Health, Kampala, Uganda. 9Zhejiang University-University of Edinburgh -

Public Notice

PUBLIC NOTICE PROVISIONAL LIST OF TAXPAYERS EXEMPTED FROM 6% WITHHOLDING TAX FOR JANUARY – JUNE 2016 Section 119 (5) (f) (ii) of the Income Tax Act, Cap. 340 Uganda Revenue Authority hereby notifies the public that the list of taxpayers below, having satisfactorily fulfilled the requirements for this facility; will be exempted from 6% withholding tax for the period 1st January 2016 to 30th June 2016 PROVISIONAL WITHHOLDING TAX LIST FOR THE PERIOD JANUARY - JUNE 2016 SN TIN TAXPAYER NAME 1 1000380928 3R AGRO INDUSTRIES LIMITED 2 1000049868 3-Z FOUNDATION (U) LTD 3 1000024265 ABC CAPITAL BANK LIMITED 4 1000033223 AFRICA POLYSACK INDUSTRIES LIMITED 5 1000482081 AFRICAN FIELD EPIDEMIOLOGY NETWORK LTD 6 1000134272 AFRICAN FINE COFFEES ASSOCIATION 7 1000034607 AFRICAN QUEEN LIMITED 8 1000025846 APPLIANCE WORLD LIMITED 9 1000317043 BALYA STINT HARDWARE LIMITED 10 1000025663 BANK OF AFRICA - UGANDA LTD 11 1000025701 BANK OF BARODA (U) LIMITED 12 1000028435 BANK OF UGANDA 13 1000027755 BARCLAYS BANK (U) LTD. BAYLOR COLLEGE OF MEDICINE CHILDRENS FOUNDATION 14 1000098610 UGANDA 15 1000026105 BIDCO UGANDA LIMITED 16 1000026050 BOLLORE AFRICA LOGISTICS UGANDA LIMITED 17 1000038228 BRITISH AIRWAYS 18 1000124037 BYANSI FISHERIES LTD 19 1000024548 CENTENARY RURAL DEVELOPMENT BANK LIMITED 20 1000024303 CENTURY BOTTLING CO. LTD. 21 1001017514 CHILDREN AT RISK ACTION NETWORK 22 1000691587 CHIMPANZEE SANCTUARY & WILDLIFE 23 1000028566 CITIBANK UGANDA LIMITED 24 1000026312 CITY OIL (U) LIMITED 25 1000024410 CIVICON LIMITED 26 1000023516 CIVIL AVIATION AUTHORITY -

Uganda Police Force Anti - Corruption Strategy

UGANDA POLICE FORCE ANTI - CORRUPTION STRATEGY From Colonial Policing to Community Policing 2017/18-2021/22 Uganda Police Headquarters Naguru Plot 42/49, Katalima Road, P.o Box 7055, Kampala Uganda Fax: +256-414-343531/255630. General Lines: 256-414-343532/233814/231761/254033 Toll Free: 0800-199-699, 0800-199-499.Website: http://www.upf.go.ug Aligned to the JLOS Anti-corruption strategy With Support from Contents FOREWORD ........................................................................................... 4 LIST OF ACRONYMS ............................................................................ 6 CHAPTER ONE: BACKGROUND ........................................................ 8 1.0 Introduction ................................................................................... 8 With Support from 1.1 Situational analysis ..................................................................... 10 1.2 Definition of Corruption ............................................................. 12 1.3 The Police Mandate .................................................................... 15 1.4 Forms of corruption in the UPF .................................................. 16 1.5 Factors influencing corruption in UPF ........................................ 17 CHAPTER 2: EXISTING LEGAL AND INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK TO FIGHT CORRUPTION IN UGANDA ................. 21 2.0 Introduction ................................................................................. 21 2.1 NRM Ten Point programme ...................................................... -

IGG Report 2017.Indd

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA BI-ANNUALBI-ANNUAL INSPECTORATE INSPECTORATE OF GOVERNMENTGOVERNMENT PERFORMANCEPERFORMANCE REPORT REPORT TOTO PARLIAMENTPARLIAMENT JANUARY - JUNE 2017 MandateMandate To promote just utilization of public resources VisionVision A responsive and accountable public sector MissionMission To promote good governance, accountability and rule of law in public offfice CCoreore ValuesValues Integrity Impartiality Professionalism Gender Equality and Equity INSPECTORATE OF GOVERNMENT BI-ANNUAL INSPECTORATE OF GOVERNMENT PERFORMANCE REPORT TO PARLIAMENT JANUARY – JUNE 2017 THE LEADERSHIP OF THE INSPECTORATE OF GOVERNMENT Justice Irene Mulyagonja Kakooza Inspector General of Government Ms. Mariam Wangadya Mr. George Bamugemereire Deputy Inspector General of Deputy Inspector General of Government Government Ms. Rose N. Kafeero Secretary to the Inspectorate of Government THE INSPECTORATE OF GOVERNMENT Jubilee Insurance Centre, Plot 14, Parliament Avenue P.O. Box 1682 Kampala, Uganda General Lines: 0414-255892/259738 z Hotlines: 0414-347387/0312-101346 Fax: 0414-344810 z Email: [email protected] z Website: www.igg.go.ug Facebook: Inspectorate of Government z Twitter: @IGGUganda YouTube: Inspectorate of Government OFFICE OF THE INSPECTOR GENERAL OF GOVERNMENT Inspector General of Government Justice Irene Mulyagonja Kakooza Tel: 0414-259723 z Email: [email protected] Deputy Inspector General of Government Deputy Inspector General of Government Mr. George Bamugemereire Ms. Mariam Wangadya Tel: 0414-259780 Tel: 0414-259709 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Department of Finance and Administration: Secretary to the Inspectorate of Government Undersecretary Finance and Administration Ms. Rose N. Kafeero Ms. Glory Anaƾun Tel: 0414-259788; Fax: 0414-257590 Tel: 0414-230398 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Information and Internal Inspection Division Public and International Relations Division Head of Division: Mr. -

The Inspector General of Government and the Question of Political Corruption in Uganda

Frustrated Or Frustrating S AND P T EA H C IG E R C E N N A T M E U R H H URIPEC FRUSTRATED OR FRUSTRATING? THE INSPECTOR GENERAL OF GOVERNMENT AND THE QUESTION OF POLITICAL CORRUPTION IN UGANDA Daniel Ronald Ruhweza HURIPEC WORKING PAPER NO. 20 November, 2008 Frustrated Or Frustrating FRUSTRATED OR FRUSTRATING? THE INSPECTOR GENERAL OF GOVERNMENT AND THE QUESTION OF POLITICAL CORRUPTION IN UGANDA Daniel R. Ruhweza HURIPEC WORKING PAPER No. 20 NOVEMBER, 2008 Frustrated Or Frustrating FRUSTRATED OR FRUSTRATING? THE INSPECTOR GENERAL OF GOVERNMENT AND THE QUESTION OF POLITICAL CORRUPTION IN UGANDA aniel R. Ruhweza Copyright© Human Rights & Peace Centre, 2008 ISBN 9970-511-24-8 HURIPEC Working Paper No. 20 NOVEMBER 2008 Frustrated Or Frustrating TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS...................................................................................... i LIST OF ACRONYMS/ABBREVIATIONS......................………..………............ ii LIST OF LEGISLATION & INTERNATIONAL CONVENTIONS….......… iii LIST OF CASES …………………………………………………….. .......… iv SUMMARY OF THE REPORT AND MAIN RECOMMENDATIONS……...... v I: INTRODUCTION ………………………………………………........ 1 1.1 Working Definitions….………………............................................................... 5 1.1.1 The Phenomenon of Corruption ……………………………………....... 5 1.1.2 Corruption in Uganda……………………………………………….... 6 II: RATIONALE FOR THE CREATION OF THE INSPECTORATE … .... 9 2.1 Historical Context …………………………………………………............ 9 2.2 Original Mandate of the Inspectorate.………………………….…….......... 9 2.3 -

Report to Parliament

INSPECTORATE OF GOVERNMENT INSPECTORATE OF GOVERNMENT REPORT TO PARLIAMENT JANUARY - JUNE 2014 REPORT TO PARLIAMENT 1 JANUARY-JUNE 2014 INSPECTORATE OF GOVERNMENT JANUARY-JUNE 2014 2 REPORT TO PARLIAMENT INSPECTORATE OF GOVERNMENT INSPECTORATE OF GOVERNMENT REPORT TO PARLIAMENT JANUARY - JUNE 2014 REPORT TO PARLIAMENT 3 JANUARY-JUNE 2014 INSPECTORATE OF GOVERNMENT JANUARY-JUNE 2014 4 REPORT TO PARLIAMENT INSPECTORATE OF GOVERNMENT INSPECTORATE OF GOVERNMENT HEAD OFFICE Jubilee Insurance Centre. Plot 14, Parliament Avenue. P. O. Box 1682 Kampala Tel: +256-414 344 219 | +256-414 259 738 (General lines) +256-414 255 892 | +256-414 251 462 (Hotline) +256-414 347 387 Fax: +256-414 344 810 | Website: www.igg.go.ug Vision: Mission: Core Values: “Good Governance To Promote Good Governance through Integrity, with an Ethical and enhancing accountability, Transparency Impartiality Corruption Free and the enforcement of the rule of law Professionalism Society” and administrative justice in public Gender Equality and offices Equity OFFICE OF THE INSPECTOR GENERAL OF GOVERNMENT Inspector General of Government Ms. Irene Mulyagonja Kakooza Tel: +256 414 259 723 | Fax: +256 414 344 810 +256 414 257 590 | Email: [email protected] Deputy Inspector General of Government Information and Internal Inspection Division Mr. George Nathan Bamugemereire Head: Mr. Stephen Kasirye Tel: +256 414 259780 Tel: +256 414 342113 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Deputy Inspector General of Government Public and International Relations Division Ms. Mariam Wangadya Head: Ms. Munira Ali Bablo Tel: +256 414 259709 Tel: +256 414 231530 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] DEPARTMENT OF FINANCE AND ADMINISTRATION Secretary to the Inspectorate of Government Undersecretary finance and Administration Mr. -

Uganda 1 – 31 January 2021

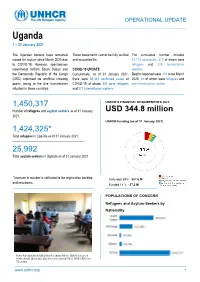

OPERATIONAL UPDATE Uganda 1 – 31 January 2021 The Ugandan borders have remained These movements cannot be fully verified The cumulative number includes closed for asylum since March 2020 due and accounted for. 14,114 recoveries, 372 of whom were to COVID-19. However, spontaneuos refugees and 229 humanitarian movements to/from South Sudan and COVID-19 UPDATE workers. the Democratic Republic of the Congo Cumulatively, as of 31 January 2021, Deaths reported were 318 since March (DRC) continued via unofficial crossing there were 39,314 confirmed cases of 2020, six of whom were refugees and points, owing to the dire humanitarian COVID-19, of whom, 381 were refugees one humanitarian worker. situation in these countries. and 277 humanitarian workers. cannot be fully verified and accounted 1,450,317 UNHCR’S FINANCIAL REQUIREMENTS 2021: Number of refugees and asylum seekers as of 31 January USD 344.8 million 2021. UNHCR Funding (as of 31 January 2021) 1,424,325* Total refugees in Uganda as of 31 January 2021. 25,992 Total asylum-seekers in Uganda as of 31 January 2021. *Increase in number is attributed to the registration backlog Unfunded 89% - 307.6 M and new-borns. Funded 11 % - 37.2 M POPULATIONS OF CONCERN Refugees and Asylum-Seekers by Nationality Senior four students at Valley View Secondary School, Bidibidi settlement, Yumbe district attend class after schools re-opened. Photo ©UNHCR/Yonna Tukundane www.unhcr.org 1 OPERATIONAL UPDATE > UGANDA / 1 – 31 January 2021 A senior four candidate at Valley View Secondary School, Bidibidi settlement, Yumbe district, studies in preparation for his final examinations. -

Fighting Corruption in Uganda: Despite Small Gains, Citizens Pessimistic About Their Role

Dispatch No. 77 | 28 March 2016 Fighting corruption in Uganda: Despite small gains, citizens pessimistic about their role Afrobarometer Dispatch No. 77 | John Martin Kewaza Summary Uganda’s widespread corruption is highlighted in the country’s poor ranking (139th out of 167 countries) in the Corruption Perceptions Index as well as in the recent Africa edition of the Global Corruption Barometer (Transparency International, 2015a, b). Pernicious effects stretch from substandard public services through elections and the judiciary to stunted economic development. In 2012, four in 10 respondents (41%) in an Afrobarometer survey reported that they had been offered money or a gift in return for their votes during the 2011 elections. In petitioning Parliament last year to appoint a commission of inquiry, retired Supreme Court Judge Justice George Kanyeihamba said, “There is evidence of inefficiency, incompetence, and corruption in the judiciary and unethical conduct by members of the bar” (Parliament of Uganda, 2015). The Black Monday Movement, a coalition of anti- corruption civil society organisations, estimates that between 2000 and 2014, the government lost more than Shs. 24 trillion to corruption – enough to finance the country’s 2015/2016 budget (ActionAid Uganda, 2015) The government’s strategies to fight corruption include the National Anti-Corruption Strategy (NACS), the Anti-Corruption Act, and the establishment of a specialized anti-corruption court within the judiciary. Internationally, Uganda has been a signatory of the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) as well as the African Union Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption since 2004. Many civil society organisations have joined the anti-corruption fight, including the Anti- Corruption Coalition, Transparency International Uganda, the African Parliamentarians Network against Corruption, Civil Society Today, the Uganda Debt Network, and the NGO Forum (Martini, 2013).