Chapter 1 Men and Manliness in British Society 1780-1870

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scott's Discovery Expedition

New Light on the British National Antarctic Expedition (Scott’s Discovery Expedition) 1901-1904. Andrew Atkin Graduate Certificate in Antarctic Studies (GCAS X), 2007/2008 CONTENTS 1 Preamble 1.1 The Canterbury connection……………...………………….…………4 1.2 Primary sources of note………………………………………..………4 1.3 Intent of this paper…………………………………………………...…5 2 Bernacchi’s road to Discovery 2.1 Maria Island to Melbourne………………………………….…….……6 2.2 “.…that unmitigated fraud ‘Borky’ ……………………….……..….….7 2.3 Legacies of the Southern Cross…………………………….…….…..8 2.4 Fellowship and Authorship………………………………...…..………9 2.5 Appointment to NAE………………………………………….……….10 2.6 From Potsdam to Christchurch…………………………….………...11 2.7 Return to Cape Adare……………………………………….….…….12 2.8 Arrival in Winter Quarters-establishing magnetic observatory…...13 2.9 The importance of status………………………….……………….…14 3 Deeds of “Derring Doe” 3.1 Objectives-conflicting agendas…………………….……………..….15 3.2 Chivalrous deeds…………………………………….……………..…16 3.3 Scientists as Heroes……………………………….…….……………19 3.4 Confused roles……………………………….……..………….…...…21 3.5 Fame or obscurity? ……………………………………..…...….……22 2 4 “Scarcely and Exhibition of Control” 4.1 Experiments……………………………………………………………27 4.2 “The Only Intelligent Transport” …………………………………….28 4.3 “… a blasphemous frame of mind”……………………………….…32 4.4 “… far from a picnic” …………………………………………………34 4.5 “Usual retine Work diggin out Boats”………...………………..……37 4.6 Equipment…………………………………………………….……….38 4.8 Reflections on management…………………………………….…..39 5 “Walking to Christchurch” 5.1 Naval routines………………………………………………………….43 -

List of the Oedinary Fellows of the Society

LIST OF THE OEDINARY FELLOWS OF THE SOCIETY. N.B.—Those marked * are Annual Contributors. 1846 Alex. J. Adie, Esq., Rockville, Linlithgow 1872 "Archibald Constable, Esq., 11 Thistle Street 1871 *Stair Agnew, Esq, 22 Buckingham Terrace 1843 Sir John Rose Cormack, M.D., 7 Rue d'Aguesseau, 1875 "John Aitken, Esq., Darroch, Falkirk Paris 1866 "Major-General Sir James E. Alexander of Westerton, 1872 "The Right Rev. Bishop Cotterill (VICE-PRESIDENT), 1 ' Bridge of Allan Atholl Place. 1867 "Rev. Dr W. Lindsay Alexander (VICE-PRESIDENT), 1843 Andrew Coventry, Esq., Advocate, 29 Moray Place Pinkie Burn, Musselburgh 1863 "Charles Cowan, Esq., Westerlea, Murrayfield 1848 Dr James Allan, Inspector of Hospitals, Portsmouth 1854 "Sir James Coxe, M.D., Kinellan 1856 Dr George J. Allinan, Emeritus Professor of Natural 1830 J. T. Gibson-Craig, Esq., W.S., 24 York Place History, Wimbledon, London 1829 Sir William Gibson-Craig, Bart., Riccarton 1849 David Anderson, Esq., Moredun, Edinburgh 1875 "Dr William Craig, 7 Lothian Road 1872 John Anderson, LL.D., 32 Victoria Road, Charlton, 1873 "Donald Crawford, Esq., Advocate, 18 Melville Street 70 Kent 1853 Rev. John Cumming, D.D., London 1874 Dr John Anderson, Professor of Comparative Anatomy, 1852 "James Cunningham, Esq., W.S., 50 Queen Street Medical College, Calcutta 10 1871 "Dr R. J. Blair Cunyninghame, 6 Walker Street 1823 Warren Hastings Anderson, Esq., Isle of Wight 1823 Liscombe J. Curtis, Esq., Ingsdown House, Devonshire 1867 "Thomas Annandale, Esq., 34 Charlotte Square 1862 *T. C. Archer, Esq., Director of the Museum of Science 1851 E. W. Dallas, Esq., 34 Hanover Street and Art, 5 West Newington Terrace 1841 James Dalmahoy, Esq., 9 Forres Street 1849 His Grace the Duke of Argyll, K.T., (HON. -

References Geological Society, London, Memoirs

Geological Society, London, Memoirs References Geological Society, London, Memoirs 2002; v. 25; p. 297-319 doi:10.1144/GSL.MEM.2002.025.01.23 Email alerting click here to receive free email alerts when new articles cite this article service Permission click here to seek permission to re-use all or part of this article request Subscribe click here to subscribe to Geological Society, London, Memoirs or the Lyell Collection Notes Downloaded by on 3 November 2010 © 2002 Geological Society of London References ABBATE, E., BORTOLOTTI, V. & PASSERINI, P. 1970. Olistostromes and olis- ARCHER, J. B, 1980. Patrick Ganly: geologist. Irish Naturalists' Journal, 20, toliths. Sedimentary Geology, 4, 521-557. 142-148. ADAMS, J. 1995. Mines of the Lake District Fells. Dalesman, Skipton (lst ARTER. G. & FAGIN, S. W. 1993. The Fieetwood Dyke and the Tynwald edn, 1988). fault zone, Block 113/27, East Irish Sea Basin. In: PARKER, J. R. (ed.), AGASSIZ, L. 1840. Etudes sur les Glaciers. Jent & Gassmann, Neuch~tel. Petroleum Geology of Northwest Europe: Proceedings of the 4th Con- AGASSIZ, L. 1840-1841. On glaciers, and the evidence of their once having ference held at the Barbican Centre, London 29 March-1 April 1992. existed in Scotland, Ireland and England. Proceedings of the Geo- Geological Society, London, 2, 835--843. logical Society, 3(2), 327-332. ARTHURTON, R. S. & WADGE A. J. 1981. Geology of the Country Around AKHURST, M. C., BARNES, R. P., CHADWICK, R. A., MILLWARD, D., Penrith: Memoir for 1:50 000 Geological Sheet 24. Institute of Geo- NORTON, M. G., MADDOCK, R. -

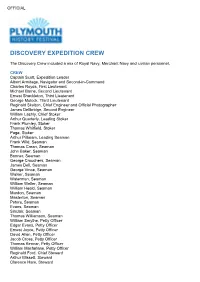

Discovery: Crew List

OFFICIAL DISCOVERY EXPEDITION CREW The Discovery Crew included a mix of Royal Navy, Merchant Navy and civilian personnel. CREW Captain Scott, Expedition Leader Albert Armitage, Navigator and Second-in-Command Charles Royds, First Lieutenant Michael Barne, Second Lieutenant Ernest Shackleton, Third Lieutenant George Mulock, Third Lieutenant Reginald Skelton, Chief Engineer and Official Photographer James Dellbridge, Second Engineer William Lashly, Chief Stoker Arthur Quarterly, Leading Stoker Frank Plumley, Stoker Thomas Whitfield, Stoker Page, Stoker Arthur Pilbeam, Leading Seaman Frank Wild, Seaman Thomas Crean, Seaman John Baker, Seaman Bonner, Seaman George Crouchers, Seaman James Dell, Seaman George Vince, Seaman Walker, Seaman Waterman, Seaman William Weller, Seaman William Heald, Seaman Mardon, Seaman Masterton, Seaman Peters, Seaman Evans, Seaman Sinclair, Seaman Thomas Williamson, Seaman William Smythe, Petty Officer Edgar Evans, Petty Officer Ernest Joyce, Petty Officer David Allan, Petty Officer Jacob Cross, Petty Officer Thomas Kennar, Petty Officer William Macfarlane, Petty Officer Reginald Ford, Chief Steward Arthur Blissett, Steward Clarence Hare, Steward OFFICIAL Dowsett, Steward Gilbert Scott, Steward Roper, Cook Brett, Cook Charles Clarke, 2nd Cook Clarke, Laboratory Assistant Buckridge, Laboratory Assistant Fred Dailey, Carpenter James Duncan, Carpenter’s Mate & Shipwright Thomas Feather, Boatswain (Bosun) Miller, Sailmaker Hubert, Donkeyman SCIENTIFIC Dr George Murray, Chief Scientist (left the ship at Cape Town) Louis Bernacchi, Physicist Hartley Ferrar, Geologist Thomas Vere Hodgson, Marine Biologist Reginald Koettlitz, Doctor Edward Wilson, Junior Doctor and Zoologist . -

HISTORY Discover Your Legislature Series

HISTORY Discover Your Legislature Series Legislative Assembly of British Columbia Victoria British Columbia V8V 1X4 CONTENTS UP TO 1858 1 1843 – Fort Victoria is Established 1 1846 – 49th Parallel Becomes International Boundary 1 1849 – Vancouver Island Becomes a Colony 1 1850 – First Aboriginal Land Treaties Signed 2 1856 – First House of Assembly Elected 2 1858 – Crown Colony of B.C. on the Mainland is Created 3 1859-1870 3 1859 – Construction of “Birdcages” Started 3 1863 – Mainland’s First Legislative Council Appointed 4 1866 – Island and Mainland Colonies United 4 1867 – Dominion of Canada Created, July 1 5 1868 – Victoria Named Capital City 5 1871-1899 6 1871 – B.C. Joins Confederation 6 1871 – First Legislative Assembly Elected 6 1872 – First Public School System Established 7 1874 – Aboriginals and Chinese Excluded from the Vote 7 1876 – Property Qualification for Voting Dropped 7 1886 – First Transcontinental Train Arrives in Vancouver 8 1888 – B.C.’s First Health Act Legislated 8 1893 – Construction of Parliament Buildings started 8 1895 – Japanese Are Disenfranchised 8 1897 – New Parliament Buildings Completed 9 1898 – A Period of Political Instability 9 1900-1917 10 1903 – First B.C Provincial Election Involving Political Parties 10 1914 – The Great War Begins in Europe 10 1915 – Parliament Building Additions Completed 10 1917 – Women Win the Right to Vote 11 1917 – Prohibition Begins by Referendum 11 CONTENTS (cont'd) 1918-1945 12 1918 – Mary Ellen Smith, B.C.’s First Woman MLA 12 1921 – B.C. Government Liquor Stores Open 12 1920 – B.C.’s First Social Assistance Legislation Passed 12 1923 – Federal Government Prohibits Chinese Immigration 13 1929 – Stock Market Crash Causes Great Depression 13 1934 – Special Powers Act Imposed 13 1934 – First Minimum Wage Enacted 14 1938 – Unemployment Leads to Unrest 14 1939 – World War II Declared, Great Depression Ends 15 1941 – B.C. -

OOTD April 2018

Orders of the Day The Publication of the Association of Former MLAs of British Columbia Volume 24, Number 3 April 2018 Social change advocate moves into Gov. House BCHappy has a new Lieutenant Governor Holidays, Janet Austin. Austin is a remarkable community leader and advocate for social change. She has been serving as the Chief Executive Officer of the Metro Vancouver YWCA, a position she has held since 2003. She follows Judith Guichon into Government House to take on what has been, until last year, a largely ceremonial five-year appointment. Guichon made headlines last June when she asked the NDP’s John Horgan to form government after no single party had won a majority. The announcement by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau came March 20 as Governor General Julie Payette paid her first official visit to British Columbia. She was welcomed to Government House by Guichon. It would be Her Honour’s final bow. Incoming Lieutenant Governor Janet Austin Payette signed the guest book at Government House, leaving a sticker of her new coat of arms, which features a white wing to symbolize exploration, liberty and safety. Payette, a former astronaut, was the second Canadian woman to go into space and the first Canadian on board the International Space Station. The Prime Minister and Premier John Horgan thanked the outgoing Lieutenant Governor Judith Guichon for her numerous contributions and her work to engage communities, non-profit organizations, and businesses across the province since taking office in 2012. Premier John Horgan and retiring Lieutenant Governor Judith Guichon greet continued on Page 4 Governor General Julie Payette on her first official visit to BC. -

“A Good Advertisement for Teetotallers”: Polar Explorers and Debates Over the Health Effects of Alcohol, 1875–1904

EDWARD ARMSTON-SHERET “A GOOD ADVERTISEMENT FOR TEATOTALERS”: POLAR EXPLORERS AND DEBATES OVER THE HEALTH EFFECTS OF ALCOHOL AS PUBLISHED IN THE SOCIAL HISTORY OF ALCOHOL AND DRUGS. AUTHOR’S POST-PRINT VERSION, SEPTEMBER 2019. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1086/705337 1 | P a g e “A good advertisement for teetotalers”: Polar explorers and debates over the health effects of alcohol, 1875–1904.1 Abstract: This paper examines discussions about drink and temperance on British polar expeditions around the turn of the twentieth century. In doing so, I highlight how expeditionary debates about drinking reflected broader shifts in social and medical attitudes towards alcohol. These changes meant that by the latter part of the nineteenth century, practices of expeditionary drinking could make or break the reputation of a polar explorer, particularly on an expedition that experienced an outbreak of scurvy. At the same time, I demonstrate the importance of travel and exploration in changing medical understandings of alcohol. I examine these issues through an analysis of two expeditions organized along naval lines—the British Arctic Expedition (1875–6) and the British National Antarctic Expedition (1901–4)—and, in doing so, demonstrate that studying 1 I would like to thank Dr James Kneale, Dr Innes M. Keighren, and Professor Klaus Dodds for their invaluable comments on drafts of this paper. An earlier version of this paper was also presented in a seminar at the Huntington Library, California, and benefited from the comments and suggestions of those who attended. This research was supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) through the TECHE doctoral training partnership and by an AHRC International Placement Scheme Fellowship at the Huntington Library. -

Chivalry at the Poles: British Sledge Flags PROCEEDINGS Barbara Tomlinson Curator, the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK

Chivalry at the Poles: British Sledge Flags PROCEEDINGS Barbara Tomlinson Curator, The National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK In 1999 Captain Robert Falcon Scott’s sledge flag was sold by the family and purchased at Christies on 17 September by the National Maritime Museum. This is what we may call Scott’s official sledge flag recogniz‑ able in the photographs of the ill‑fated polar party at the South Pole and subsequently recovered from their tent by Atkinson’s search party on 12 November 1912. The flag is in heavyweight silk sateen, machine-stitched with a cross of St. George at the hoist, the rest of the flag divided horizontally, white over blue. The Scott family crest of a stag’s head and the motto “Ready Aye Ready” are embroidered in brown in the centre. Photograph of one of Scott’s Expeditions Various types of flags were used on polar expeditions... ensigns, depot marking flags and the Union flag taken to plant at the Pole should a sledge party arrive there. There is quite a close relationship between sledge flags and boat flags. British expeditions were seeking a route through the Canadian archipelago or attempting to reach Captain R F Scott’s Sledge Flag the North Pole over the sea ice of the Arctic Ocean- a This is not the only surviving sledge flag belonging to complicated mix of ice and water. William Edward Parry’s Scott, another of similar design, carried on his first expe‑ North Pole expedition of 1827 used sledges and boats dition in Discovery was presented to Exeter Cathedral constructed with runners to cross the hummocky pack ice by his mother and now hangs on the south wall of the and the channels of water which opened up in summer. -

Sir Clement Molyneux Royds, C.B

THE OF BY SIR CLEMENT MOLYNEUX ROYDS, C.B. LONDON: MITCHELL HUGHES AND CLARKE, 140 WARDOUR STREET, W. 1910. INTRODUCTION. THE following Pages, which I believe will be of interest io the members of the numerous family of RoYns, are the outcome of leisure moments from early days, and in later years owing much to the happy assistance of my Wife. To my cousin Edmund Royds, M.P., of Holy Cross, Caythorpe, Grantham, I am greatly indebted for his research and valuable authentication of the Family during its domicile in the West Riding of Yorkshire ; and the kind assistance in various ways of other members, including those in New Zealand, I cannot too gratefully acknowledge. CLEMENT M. ROYDS. GREENHILL, 1910. CONTENTS • • l'A&B Pedigrees- Beswicke • • • • • . • • • • • • 68 Calverley • • • • • • • • • • • • 4:7 Clegg • • • • • • • • • • • • • 42 Gilbert . • • • • • • • • • • • • 36 Hudson • • • • • • • • • • • • 43 Littledale • • • • • • • • • • • • 59 Meadowcroft. • • • • • • • • • • • 55 Molyneux • • • • • • • • • • • • 4:4 Rawson. • • • • • • • • • • • • 66 Royds • • • • • • • • • • • • • 2 of Brereton • 17 " • • • • • • • • • • ,, Brizes Park 82 " • • • • • • • • • • ,, Falinge 9 " • • • • • • • • • • • ,, Greenhill 28 " • • • • • • • • • • ,, Heysham and Haughton. 24 " • • • • • • • ,, Woodlands 15 " • • • • • • • • • • Smith • • • • • • • • • • • • • 88 Twemlow • • • • • • • • • • • • 56 Confirmation of Arms • • • • • • • • • • • 72 Grant of Arms • • • • • • • • • • • • 78 Monumental Inscriptions • • • • • • • • • • 75 Addenda and Corrigenda -

Piece for the Nimrod

“Antarctic Sites outside the Antarctic - Memorials, Statues, Houses, Graves and the occasional Pub” Presented at the 6th ‘Shackleton Autumn School’ Athy, Co, Kildare, Ireland, Sunday 29 October 2006 onument, Hamilton, Ohio. HE ANTARCTIC is very far from where I grew up and have spent most of T my years. As a town planner I saw little prospect of having a job that would take me there and I couldn’t afford paying money to get there. So I travelled to Antarctica in a vicarious way, collecting ‘sites’ of mainly historic interest with some association to the seventh continent but not actually there. My collection resides in what I call my “Low-Latitude Antarctic Gazetteer” and began close to forty years ago with its first entry, Captain Scott’s house at 56 Oakley Street in London (one of several associated with him but the only one bearing the coveted ‘blue plaque’). The number of entries now totals 887. Fully 144 of these relate to a greater or lesser degree to Sir Ernest Shackleton (Scott comes in second at 122, Amundsen 37). Herewith are some of my Shackleton favorites (and a few others, too): SOME HOUSES Shackleton houses abound. The first and most important is Kilkea House, not far from Athy, Co. Kildare, where Ernest was born on the morning of 15 February 1874. The house still stands in a lovely rural setting. But by 1880 the family had moved to Dublin to 35 Marlborough Road, an attractive brick row house south of the city center and one of three Shackleton houses commemorated with plaques, this particular one being unveiled on May 20, 2000. -

Assimilation Through Incarceration: The

ASSIMILATION THROUGH INCARCERATION: THE GEOGRAPHIC IMPOSITION OF CANADIAN LAW OVER INDIGENOUS PEOPLES by Madelaine Christine Jacobs A thesis submitted to the Department of Geography in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (September, 2012) Copyright ©Madelaine Christine Jacobs, 2012 Abstract The disproportionate incarceration of indigenous peoples in Canada is far more than a socio- economic legacy of colonialism. The Department of Indian Affairs (DIA) espoused incarceration as a strategic instrument of assimilation. Colonial consciousness could not reconcile evolving indigenous identities with projects of state formation founded on the epistemological invention of populating idle land with productive European settlements. The 1876 Indian Act instilled a stubborn, albeit false, categorization deep within the structures of the Canadian state: “Indian,” ward of the state. From “Indian” classification conferred at birth, the legal guardianship of the state was so far-reaching as to make it akin to the control of incarcerated inmates. As early iterations of the DIA sought to enforce the legal dominion of the state, “Indians” were quarantined on reserves until they could be purged of indigenous identities that challenged colonial hegemony. Reserve churches, council houses, and schools were symbolic markers as well as practical conveyors of state programs. Advocates of Christianity professed salvation and taught a particular idealized morality as prerequisites to acceptable membership in Canadian society. Agricultural instructors promoted farming as a transformative act in the individual ownership of land. Alongside racializing religious edicts and principles of stewardship, submission to state law was a critical precondition of enfranchisement into the adult milieu. -

I.—A Retrospect of Palaeontology in the Last Forty Years

THE GEOLOGICAL MAGAZINE. NEW SERIES. DECADE V. VOL. I. No. IV. —APRIL, 1904. ORIGI3STAL ARTICLES. I.—A KETROSPECT OF PALAEONTOLOGY IN TIIE LAST FOBTY YEABS. (Concluded from the March Number, p. 106.) EEPTILIA ET AVES.—Our two greatest Anatomists of the past century, Owen and Huxley, both contributed to this section of our palseozoological record. Owen (in 1865) described some remains of a small air-breathing vertebrate, Anihrakerpeton crassosteum, from the Coal-shales of Glamorganshire, corresponding with those described by Dawson from the Coal-measures of Nova Scotia ; and in 1870 he noticed some remains of Plesiosaurus Hoodii (Owen) from New Zealand, possibly of Triaasic age. Huxley made us acquainted with an armed Dinosaur from the Chalk-marl of Folkestone, allied to Scelidosaurus (Liassic), ITylao- saurus and Polacanthus (Wealden), the teeth and dermal spines of which he described and figured (1867), and in the following year he figured and determined two new genera of Triassic reptilia, Saurosternon Bainii and Pristerodon McKayi, from the Dicynodont beds of South Africa. E. Etheridge recorded (in 1866) the discovery by Dr. E. P. Wright and Mr. Brownrig of several new genera of Labyrinthodonts in the Coal-shales of Jarrow Colliery, Kilkenny, Ireland, com- municated by Huxley to the Royal Irish Academy, an account of which appeared later on in the GEOLOGICAL MAGAZINE in the same year by Dr. E. P. Wright (p. 165), the genera given being Urocordylus, Ophiderpeton, Ichthyerpeton, Keraterpeton, Lepterpeton, and Anthracosaurus. Besides these genera there were indications of the existence of several others (not described), making at that time a total of thirteen genera from the Carboniferous formation in general.