Piece for the Nimrod

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

E R N E S T Shackleton

THE FOURTEENTH ERNEST SHACKLETON AUTUMN SCHOOL 24- 27TH OCTOBER 2014 ATHY HERITAGE CENTRE MUSEUM LECTURES . EXHIBITION . FILM . DRAMA . EXCURSIONS ENDURANCE CENTENARY PERFORMANCE www.shackletonmuseum.com/autumn_school/2014 . Tel: (059) 863 3075 Sir Ernest Shackleton Born close to the village of Kilkea, Friday 24th October between Castledermot and Athy, in the south Official Opening Athy Heritage Centre - Museum of County Kildare in 1874, Ernest Shackleton is renowned for his courage, his commitment & Exhibition Launch by to the welfare of his comrades, and his 7.30pm Mr Peter Carey, Chief Executive of Kildare County Council immense contribution to exploration and geographical discovery. The Shackleton family Book Launch first came to south Kildare in the early years 8.00pm In association with the Collins Press of the eighteenth century. Ernest’s Quaker the school will host the launch of forefather, Abraham Shackleton, established a multi-denominational school in the village Shackleton: By Endurance We Conquer by of Ballitore. This school was to educate such Michael Smith. notable figures as Napper Tandy, Edmund The book is the first comprehensive Burke, Cardinal Paul Cullen and Shackleton’s great aunt, the Quaker writer, Mary Leadbeater. biography of Shackleton in a generation. Apart from their involvement in education, the The book will be launched by Aidan extended family was also deeply involved in Dooley, actor, writer, director and the the business and farming life of south Kildare. Having gone to sea as a teenager, creator of the acclaimed one man show, Shackleton joined Captain Scott’s Discovery “Tom Crean - Antarctic Explorer”. expedition (1901 – 1904) and, in time, was to lead three of his own expeditions to the Antarctic. -

Scott's Discovery Expedition

New Light on the British National Antarctic Expedition (Scott’s Discovery Expedition) 1901-1904. Andrew Atkin Graduate Certificate in Antarctic Studies (GCAS X), 2007/2008 CONTENTS 1 Preamble 1.1 The Canterbury connection……………...………………….…………4 1.2 Primary sources of note………………………………………..………4 1.3 Intent of this paper…………………………………………………...…5 2 Bernacchi’s road to Discovery 2.1 Maria Island to Melbourne………………………………….…….……6 2.2 “.…that unmitigated fraud ‘Borky’ ……………………….……..….….7 2.3 Legacies of the Southern Cross…………………………….…….…..8 2.4 Fellowship and Authorship………………………………...…..………9 2.5 Appointment to NAE………………………………………….……….10 2.6 From Potsdam to Christchurch…………………………….………...11 2.7 Return to Cape Adare……………………………………….….…….12 2.8 Arrival in Winter Quarters-establishing magnetic observatory…...13 2.9 The importance of status………………………….……………….…14 3 Deeds of “Derring Doe” 3.1 Objectives-conflicting agendas…………………….……………..….15 3.2 Chivalrous deeds…………………………………….……………..…16 3.3 Scientists as Heroes……………………………….…….……………19 3.4 Confused roles……………………………….……..………….…...…21 3.5 Fame or obscurity? ……………………………………..…...….……22 2 4 “Scarcely and Exhibition of Control” 4.1 Experiments……………………………………………………………27 4.2 “The Only Intelligent Transport” …………………………………….28 4.3 “… a blasphemous frame of mind”……………………………….…32 4.4 “… far from a picnic” …………………………………………………34 4.5 “Usual retine Work diggin out Boats”………...………………..……37 4.6 Equipment…………………………………………………….……….38 4.8 Reflections on management…………………………………….…..39 5 “Walking to Christchurch” 5.1 Naval routines………………………………………………………….43 -

Who Was Ernest Shackleton?

Aim • To explain who Ernest Shackleton was, and what he achieved. SuccessSuccess Criteria • ToStatement know about 1 Lorem his earlyipsum life. dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. • ToStatement recall his 2 expeditions and what he discovered. • Sub statement Watch this short video about the life of the famous polar explorer Ernest Shackleton Ernest Shackleton - Bing video Who Was Ernest Shackleton? Ernest Shackleton was born in Ireland in 1874. He was the second oldest of 10 children. He lived in Ireland until 1884, when his family moved to South London. Who Was Ernest Shackleton? Ernest loved reading, and had a great imagination. He loved the idea of going on great adventures. His father was a doctor and wanted Ernest to follow in his footsteps. However, Ernest had a different idea about what he wanted to do. What Did Shackleton Do? At the age of just 16, Shackleton joined the Merchant Navy and became a sailor. At just 18, he had been promoted to first mate. He was able to fulfil his dreams of having adventures and sailing all over the world. He wanted to become an explorer. First Mate – the officer second in command to the master of the ship. Where Did Shackleton Want to Explore? Shackleton wanted to be a polar explorer. He wanted to be the first person to reach the South Pole. In 1901, he went on his first Antarctic expedition, aged just 25. He joined another explorer, Robert Scott, and he came closer to the South Pole than anyone had before him. Unfortunately, he became ill, and had to return before reaching the South Pole. -

We Look for Light Within

“We look for light from within”: Shackleton’s Indomitable Spirit “For scientific discovery, give me Scott; for speed and efficiency of travel, give me Amundsen; but when you are in a hopeless situation, when you are seeing no way out, get down on your knees and pray for Shackleton.” — Raymond Priestley Shackleton—his name defines the “Heroic Age of Antarctica Exploration.” Setting out to be the first to the South Pole and later the first to cross the frozen continent, Ernest Shackleton failed. Sent home early from Robert F. Scott’s Discovery expedition, seven years later turning back less than 100 miles from the South Pole to save his men from certain death, and then in 1914 suffering disaster at the start of the Endurance expedition as his ship was trapped and crushed by ice, he seems an unlikely hero whose deeds would endure to this day. But leadership, courage, wisdom, trust, empathy, and strength define the man. Shackleton’s spirit continues to inspire in the 100th year after the rescue of the Endurance crew from Elephant Island. This exhibit is a learning collaboration between the Rauner Special Collections Library and “Pole to Pole,” an environmental studies course taught by Ross Virginia examining climate change in the polar regions through the lens of history, exploration and science. Fifty-one Dartmouth students shared their research to produce this exhibit exploring Shackleton and the Antarctica of his time. Discovery: Keeping Spirits Afloat In 1901, the first British Antarctic expedition in sixty years commenced aboard the Discovery, a newly-constructed vessel designed specifically for this trip. -

After Editing

Shackleton Dates AUGUST 8th 1914 The team leave the UK on the ship, Endurance. DEC 5th 1914 They arrive at the edge of the Antarctic pack ice, in the Weddell Sea. JAN 18th 1915 Endurance becomes frozen in the pack ice. OCT 27TH 1915 Endurance is crushed in the ice after drifting for 9 months. Ship is abandoned and crew start to live on the pack ice. NOV 1915 Endurance sinks; men start to set up a camp on the ice. DEC 1915 The pack ice drifts slowly north; Patience camp is set up. MARCH 23rd 2016 They see land for the first time – 139 days have passed; the land can’t be reached though. APRIL 9th 2016 The pack ice starts to crack so the crew take to the lifeboats. APRIL 15th 1916 The 3 crews arrive on ELEPHANT ISLAND where they set up camp. APRIL 24th 1916 5 members of the team, including Shackleton, leave in the lifeboat James Caird, on an 800 mile journey to South Georgia, for help. MAY 10TH 1916 The James Caird crew arrive in the south of South Georgia. MAY 19TH -20TH Shackleton, Crean and Worsley walk across South Georgis to the whaling station at Stromness. MAY 23RD 1916 All the men on Elephant Island are safe; Shackleton starts on his first attempt at a rescue from South Georgia but ice prevents him. AUGUST 25th Shackleton leaves on his 4th attempt, on the Chilian tug boat Yelcho; he arrives on Elephant Island on August 30th and rescues all his crew. MAY 1917 All return to England. -

THE PUBLICATION of the NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY Vol 34, No

THE PUBLICATION OF THE NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY Vol 34, No. 3, 2016 34, No. Vol 03 9 770003 532006 Vol 34, No. 3, 2016 Issue 237 Contents www.antarctic.org.nz is published quarterly by the New Zealand Antarctic Society Inc. ISSN 0003-5327 30 The New Zealand Antarctic Society is a Registered Charity CC27118 EDITOR: Lester Chaplow ASSISTANT EDITOR: Janet Bray New Zealand Antarctic Society PO Box 404, Christchurch 8140, New Zealand Email: [email protected] INDEXER: Mike Wing The deadlines for submissions to future issues are 1 November, 1 February, 1 May and 1 August. News 25 Shackleton’s Bad Lads 26 PATRON OF THE NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY: From Gateway City to Volunteer Duty at Scott Base 30 Professor Peter Barrett, 2008 NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY How You Can Help Us Save Sir Ed’s Antarctic Legacy 33 LIFE MEMBERS The Society recognises with life membership, First at Arrival Heights 34 those people who excel in furthering the aims and objectives of the Society or who have given outstanding service in Antarctica. They are Conservation Trophy 2016 36 elected by vote at the Annual General Meeting. The number of life members can be no more Auckland Branch Midwinter Celebration 37 than 15 at any one time. Current Life Members by the year elected: Wellington Branch – 2016 Midwinter Event 37 1. Jim Lowery (Wellington), 1982 2. Robin Ormerod (Wellington), 1996 3. Baden Norris (Canterbury), 2003 Travelling with the Huskies Through 4. Bill Cranfield (Canterbury), 2003 the Transantarctic Mountains 38 5. Randal Heke (Wellington), 2003 6. Bill Hopper (Wellington), 2004 Hillary’s TAE/IGY Hut: Calling all stories 40 7. -

The Nimrod Antarctic Expedition

THE NIMROD ANTARCTIC EXPENDITION Dr. W. A. Rupert Michell (1879-1966) Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton (1874-1922), a giant of Antarctic exploration, made four journeys into the earth’s most southerly continent. On the Discovery Expedition of 1901-1904 he was Third Officer to Robert Falcon Scott (1868-1912)1. Then, between 1907 and 1922, he organized and led three expeditions2 himself. On the first of these his team included a 28-year- old doctor from Perth, Ontario, W. A. R. Michell. William Arthur ‘Rupert’ Michell was born at Perth, on October 18, 1879, the second son of Francis Lambton Michell (1849-1928) and Margaret Helen Bell (1854-1930). His father was, first, a teacher and later principal at the Perth Collegiate Institute and then, County Inspector of Public Schools. Michell received his primary and secondary education at Perth and in 1902 graduated from the University of Toronto Medical School. He was on staff at Hamilton General Hospital until 1904 when he returned to Lanark County and purchased the practice of Dr. Herbert Edwin Gage (1867-1926) at McDonalds Corners, in Dalhousie Township, north of Perth. In 1906 Michell left McDonald’s Corners and Canada for England where he planned to undertake post graduate studies. Before doing so, however, he signed on with the Elder-Dempster Line as a ship’s surgeon. The shipping line had been founded in 1868 specifically to serve travel and trade between the United Kingdom and colonial outposts on the west coast of Africa. Elder-Dempster ships provided scheduled service to-and- from Sierra Leone; Cape Palmas (Liberia); Cape Coast Castle and Accra (Ghana); Lagos, Benin Bonny and Old Calabar (Nigeria); and Fernando Po (Equatorial Guinea). -

Chilean-Navy-Day-2016-Service.Pdf

Westminster Abbey A W REATHLAYING CEREMONY AT THE GRAVE OF ADMIRAL LORD COCHRANE , TH 10 EARL OF DUNDONALD ON CHILEAN NAVY DAY Thursday 19th May 2016 11.00 am THE CHILEAN NAVY Today we honour those men and women who, over the centuries, have given their lives in defence of their country, and who, through doing so, have shown the world their courage and self-sacrifice. As a maritime country, Chile has important interests in trade and preventing the exploitation of fishing and other marine resources. The Chilean economy is heavily dependent on exports that reach the world markets through maritime transport. This is reflected by the fact that Chile is the third heaviest user of the Panama Canal. Ninety percent of its foreign trade is carried out by sea, accounting for almost fifty-five percent of its gross domestic product. The sea is vital for Chile’s economy, and the Navy exists to protect the country and serve its interests. Each year, on 21 st May, all the cities and towns throughout Chile celebrate the heroic deeds of Commander Arturo Prat and his men. On that day in 1879, Commander Arturo Prat was commanding the Esmeralda, a small wooden corvette built twenty-five years earlier in a Thames dockyard. With a sister vessel of lighter construction, the gunboat Covadonga, the Esmeralda had been left to blockade Iquique Harbour while the main fleet had been dispatched to other missions. They were confronted by two Peruvian warships, the Huáscar and the Independencia. Before battle had ensued, Commander Prat had made a rousing speech to his crew where he showed leadership to motivate them to engage in combat. -

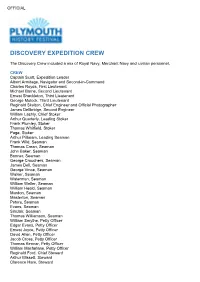

Discovery: Crew List

OFFICIAL DISCOVERY EXPEDITION CREW The Discovery Crew included a mix of Royal Navy, Merchant Navy and civilian personnel. CREW Captain Scott, Expedition Leader Albert Armitage, Navigator and Second-in-Command Charles Royds, First Lieutenant Michael Barne, Second Lieutenant Ernest Shackleton, Third Lieutenant George Mulock, Third Lieutenant Reginald Skelton, Chief Engineer and Official Photographer James Dellbridge, Second Engineer William Lashly, Chief Stoker Arthur Quarterly, Leading Stoker Frank Plumley, Stoker Thomas Whitfield, Stoker Page, Stoker Arthur Pilbeam, Leading Seaman Frank Wild, Seaman Thomas Crean, Seaman John Baker, Seaman Bonner, Seaman George Crouchers, Seaman James Dell, Seaman George Vince, Seaman Walker, Seaman Waterman, Seaman William Weller, Seaman William Heald, Seaman Mardon, Seaman Masterton, Seaman Peters, Seaman Evans, Seaman Sinclair, Seaman Thomas Williamson, Seaman William Smythe, Petty Officer Edgar Evans, Petty Officer Ernest Joyce, Petty Officer David Allan, Petty Officer Jacob Cross, Petty Officer Thomas Kennar, Petty Officer William Macfarlane, Petty Officer Reginald Ford, Chief Steward Arthur Blissett, Steward Clarence Hare, Steward OFFICIAL Dowsett, Steward Gilbert Scott, Steward Roper, Cook Brett, Cook Charles Clarke, 2nd Cook Clarke, Laboratory Assistant Buckridge, Laboratory Assistant Fred Dailey, Carpenter James Duncan, Carpenter’s Mate & Shipwright Thomas Feather, Boatswain (Bosun) Miller, Sailmaker Hubert, Donkeyman SCIENTIFIC Dr George Murray, Chief Scientist (left the ship at Cape Town) Louis Bernacchi, Physicist Hartley Ferrar, Geologist Thomas Vere Hodgson, Marine Biologist Reginald Koettlitz, Doctor Edward Wilson, Junior Doctor and Zoologist . -

Boats Built at Toledo, Ohio Including Monroe, Michigan

Boats Built at Toledo, Ohio Including Monroe, Michigan A Comprehensive Listing of the Vessels Built from Schooners to Steamers from 1810 to the Present Written and Compiled by: Matthew J. Weisman and Paula Shorf National Museum of the Great Lakes 1701 Front Street, Toledo, Ohio 43605 Welcome, The Great Lakes are not only the most important natural resource in the world, they represent thousands of years of history. The lakes have dramatically impacted the social, economic and political history of the North American continent. The National Museum of the Great Lakes tells the incredible story of our Great Lakes through over 300 genuine artifacts, a number of powerful audiovisual displays and 40 hands-on interactive exhibits including the Col. James M. Schoonmaker Museum Ship. The tales told here span hundreds of years, from the fur traders in the 1600s to the Underground Railroad operators in the 1800s, the rum runners in the 1900s, to the sailors on the thousand-footers sailing today. The theme of the Great Lakes as a Powerful Force runs through all of these stories and will create a lifelong interest in all who visit from 5 – 95 years old. Toledo and the surrounding area are full of early American History and great places to visit. The Battle of Fallen Timbers, the War of 1812, Fort Meigs and the early shipbuilding cities of Perrysburg and Maumee promise to please those who have an interest in local history. A visit to the world-class Toledo Art Museum, the fine dining along the river, with brew pubs and the world famous Tony Packo’s restaurant, will make for a great visit. -

Pardo and Shackleton: Parallel Lives; Shared Values

Pardo and Shackleton Parallel Lives, Shared Values Fiona Clouder, Her Majesty’s Ambassador to Chile Luis Pardo and Ernest Shackleton – Expedition 1914–17, led by two great figures in the shared history Ernest Shackleton, set out of two countries - UK and Chile. Two to cross Antarctica via the lives that became intertwined in one South Pole. The plan was for of the greatest rescues in history. the Weddell Sea party to sail Two men who have inspired others. on Endurance to Vahsel Bay, Two figures who lived their lives with where they would establish a shared values. Values from which we base camp from which can learn today. the crossing party would commence its journey. At the So who were Luis Pardo and Ernest same time a party would sail Shackleton? Their great achievements on Aurora to McMurdo were in an era of exploration. Shackleton Sound in the Ross Sea on is widely known as an inspirational the opposite side of the leader. He never achieved his personal continent to lay supply dream of being the first to reach the depots for the crossing party. South Pole, but his reputation as a leader of men is based on a still greater However, in 1915 Shackleton success: the survival and safe return of and his men were confronted all his team members, whilst overcoming with one of the worst disasters almost unimaginable odds. in Antarctic history: Endurance was crushed in the pack ice Perce Blackborow – a stowaway on and sank, the outside world the Endurance expedition – described was unaware of their Piloto Pardo and crew members on the deck of the Yelcho. -

Sir Ernest Shackleton: Centenary of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition

PRESS RELEASE S/49/05/16 South Georgia - Sir Ernest Shackleton: Centenary of The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, also known as the Endurance Expedition, is considered by some the last major expedition of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration. By 1914 both Poles had been reached so Shackleton set his sights on being the first to traverse Antarctica. By the time of the expedition, Sir Ernest Shackleton was already experienced in polar exploration. A young Lieutenant Shackleton from the merchant navy was chosen by Captain Scott to join him in his first bid for the South Pole in 1901. Shackleton later led his own attempt on the pole in the Nimrod expedition of 1908: he surpassed Scott’s southern record but took the courageous decision, given deteriorating health and shortage of provisions, to turn back with 100 miles to go. After the pole was claimed by Amundsen in 1911, Shackleton formulated a plan for a third expedition in which proposed to undertake “the largest and most striking of all journeys - the crossing of the Continent”. Having raised sufficient funds, he purchased a 300 tonne wooden barquentine which he named Endurance. He planned to take Endurance into the Weddell Sea, make his way to the South Pole and then to the Ross Sea via the Beardmore Glacier (to pick up supplies laid by a second vessel, Aurora, purchased from Sir Douglas Mawson). Although the expedition failed to accomplish its objective it became recognised instead as an epic feat of endurance. Endurance left Britain on 8 August 1914 heading first for Buenos Aires.