Who Was Ernest Shackleton?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

We Look for Light Within

“We look for light from within”: Shackleton’s Indomitable Spirit “For scientific discovery, give me Scott; for speed and efficiency of travel, give me Amundsen; but when you are in a hopeless situation, when you are seeing no way out, get down on your knees and pray for Shackleton.” — Raymond Priestley Shackleton—his name defines the “Heroic Age of Antarctica Exploration.” Setting out to be the first to the South Pole and later the first to cross the frozen continent, Ernest Shackleton failed. Sent home early from Robert F. Scott’s Discovery expedition, seven years later turning back less than 100 miles from the South Pole to save his men from certain death, and then in 1914 suffering disaster at the start of the Endurance expedition as his ship was trapped and crushed by ice, he seems an unlikely hero whose deeds would endure to this day. But leadership, courage, wisdom, trust, empathy, and strength define the man. Shackleton’s spirit continues to inspire in the 100th year after the rescue of the Endurance crew from Elephant Island. This exhibit is a learning collaboration between the Rauner Special Collections Library and “Pole to Pole,” an environmental studies course taught by Ross Virginia examining climate change in the polar regions through the lens of history, exploration and science. Fifty-one Dartmouth students shared their research to produce this exhibit exploring Shackleton and the Antarctica of his time. Discovery: Keeping Spirits Afloat In 1901, the first British Antarctic expedition in sixty years commenced aboard the Discovery, a newly-constructed vessel designed specifically for this trip. -

The Nimrod Antarctic Expedition

THE NIMROD ANTARCTIC EXPENDITION Dr. W. A. Rupert Michell (1879-1966) Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton (1874-1922), a giant of Antarctic exploration, made four journeys into the earth’s most southerly continent. On the Discovery Expedition of 1901-1904 he was Third Officer to Robert Falcon Scott (1868-1912)1. Then, between 1907 and 1922, he organized and led three expeditions2 himself. On the first of these his team included a 28-year- old doctor from Perth, Ontario, W. A. R. Michell. William Arthur ‘Rupert’ Michell was born at Perth, on October 18, 1879, the second son of Francis Lambton Michell (1849-1928) and Margaret Helen Bell (1854-1930). His father was, first, a teacher and later principal at the Perth Collegiate Institute and then, County Inspector of Public Schools. Michell received his primary and secondary education at Perth and in 1902 graduated from the University of Toronto Medical School. He was on staff at Hamilton General Hospital until 1904 when he returned to Lanark County and purchased the practice of Dr. Herbert Edwin Gage (1867-1926) at McDonalds Corners, in Dalhousie Township, north of Perth. In 1906 Michell left McDonald’s Corners and Canada for England where he planned to undertake post graduate studies. Before doing so, however, he signed on with the Elder-Dempster Line as a ship’s surgeon. The shipping line had been founded in 1868 specifically to serve travel and trade between the United Kingdom and colonial outposts on the west coast of Africa. Elder-Dempster ships provided scheduled service to-and- from Sierra Leone; Cape Palmas (Liberia); Cape Coast Castle and Accra (Ghana); Lagos, Benin Bonny and Old Calabar (Nigeria); and Fernando Po (Equatorial Guinea). -

Boats Built at Toledo, Ohio Including Monroe, Michigan

Boats Built at Toledo, Ohio Including Monroe, Michigan A Comprehensive Listing of the Vessels Built from Schooners to Steamers from 1810 to the Present Written and Compiled by: Matthew J. Weisman and Paula Shorf National Museum of the Great Lakes 1701 Front Street, Toledo, Ohio 43605 Welcome, The Great Lakes are not only the most important natural resource in the world, they represent thousands of years of history. The lakes have dramatically impacted the social, economic and political history of the North American continent. The National Museum of the Great Lakes tells the incredible story of our Great Lakes through over 300 genuine artifacts, a number of powerful audiovisual displays and 40 hands-on interactive exhibits including the Col. James M. Schoonmaker Museum Ship. The tales told here span hundreds of years, from the fur traders in the 1600s to the Underground Railroad operators in the 1800s, the rum runners in the 1900s, to the sailors on the thousand-footers sailing today. The theme of the Great Lakes as a Powerful Force runs through all of these stories and will create a lifelong interest in all who visit from 5 – 95 years old. Toledo and the surrounding area are full of early American History and great places to visit. The Battle of Fallen Timbers, the War of 1812, Fort Meigs and the early shipbuilding cities of Perrysburg and Maumee promise to please those who have an interest in local history. A visit to the world-class Toledo Art Museum, the fine dining along the river, with brew pubs and the world famous Tony Packo’s restaurant, will make for a great visit. -

PECS Definitions and Rulings

POLAR EXPEDITIONS CLASSIFICATION SCHEME (PECS) ! DEFINITIONS AND RULINGS The Polar Expeditions Classification Scheme is a grading system for extended, unmotorised polar expeditions, crossings or circumnavigations, collectively referred to as Journeys. Polar regions, modes of travel, start and end points, routes and types of support are defined under the scheme and give expeditioners guidance on how to classify, promote and immortalise their journey. PECS uses three tiers of Designation to grade, label and describe polar journeys - a Label (made up of Label Elements), a Description and a MAP Code. Tiers are only an indication of information density. PECS does not discriminate between Modes of Travel. Each Mode is classified under the scheme allowing same-mode journeys to be compared while allowing for superficial cross-comparison. PECS is able to accommodate new modes of unmotorised travel as they develop without impacting on labelling or definitions. Journeys using engines or motors for propulsion, for any part of the journey, are not covered by PECS. PECS concentrates primarily on journeys of more than 400km in Antarctica, Greenland and on the Arctic Ocean however journeys in other polar areas and of less than 400km one-way linear distance that do not include the Poles or significant features on their line of travel may be classified on an informal basis under this scheme. Journeys choosing to use PECS must abide by PECS terminology. Shorter journeys should be labelled accordingly ie. Last Degree South Pole or Double Degree North Pole etc. All rulings and determinations are at the discretion of the PECS Committee. POLAR EXPEDITIONS CLASSIFICATION SCHEME "1 VER190220 CONTENTS 4. -

Antarctica: at the Heart of It All

4/8/2021 Antarctica: At the heart of it all Dr. Dan Morgan Associate Dean – College of Arts & Science Principal Senior Lecturer – Earth & Environmental Sciences Vanderbilt University Osher Lifelong Learning Institute Spring 2021 Webcams for Antarctic Stations III: “Golden Age” of Antarctic Exploration • State of the world • 1910s • 1900s • Shackleton (Nimrod) • Drygalski • Scott (Terra Nova) • Nordenskjold • Amundsen (Fram) • Bruce • Mawson • Charcot • Shackleton (Endurance) • Scott (Discovery) • Shackleton (Quest) 1 4/8/2021 Scurvy • Vitamin C deficiency • Ascorbic Acid • Makes collagen in body • Limits ability to absorb iron in blood • Low hemoglobin • Oxygen deficiency • Some animals can make own ascorbic acid, not higher primates International scientific efforts • International Polar Years • 1882-83 • 1932-33 • 1955-57 • 2007-09 2 4/8/2021 Erich von Drygalski (1865 – 1949) • Geographer and geophysicist • Led expeditions to Greenland 1891 and 1893 German National Antarctic Expedition (1901-04) • Gauss • Explore east Antarctica • Trapped in ice March 1902 – February 1903 • Hydrogen balloon flight • First evidence of larger glaciers • First ice dives to fix boat 3 4/8/2021 Dr. Nils Otto Gustaf Nordenskjold (1869 – 1928) • Geologist, geographer, professor • Patagonia, Alaska expeditions • Antarctic boat Swedish Antarctic Expedition: 1901-04 • Nordenskjold and 5 others to winter on Snow Hill Island, 1902 • Weather and magnetic observations • Antarctic goes north, maps, to return in summer (Dec. 1902 – Feb. 1903) 4 4/8/2021 Attempts to make it to Snow Hill Island: 1 • November and December, 1902 too much ice • December 1902: Three meant put ashore at hope bay, try to sledge across ice • Can’t make it, spend winter in rock hut 5 4/8/2021 Attempts to make it to Snow Hill Island: 2 • Antarctic stuck in ice, January 1903 • Crushed and sinks, Feb. -

Local Climatology of Fast Ice in Mcmurdo Sound, Antarctica

Antarctic Science page 1 of 18 (2018) © Antarctic Science Ltd 2018 doi:10.1017/S0954102017000578 Local climatology of fast ice in McMurdo Sound, Antarctica STACY KIM1, BEN SAENZ2, JEFF SCANNIELLO3, KENDRA DALY4 and DAVID AINLEY5 1Moss Landing Marine Labs, 8272 Moss Landing Rd, Moss Landing, CA 95039, USA 2Resource Management Associates, 756 Picasso Ave G, Davis, CA 95618, USA 3United States Antarctic Program, 7400 S. Tucson Way, Centennial, CO 90112, USA 4University of South Florida - Saint Petersburg, 140 7th Ave S, MSL 220C, St Petersburg, FL 33701, USA 5HT Harvey and Associates, 983 University Ave, Los Gatos, CA 95032, USA [email protected] Abstract: Fast ice plays important physical and ecological roles: as a barrier to wind, waves and radiation, as both barrier and safe resting place for air-breathing animals, and as substrate for microbial communities. While sea ice has been monitored for decades using satellite imagery, high-resolution imagery sufficient to distinguish fast ice from mobile pack ice extends only back to c. 2000. Fast ice trends may differ from previously identified changes in regional sea ice distributions. To investigate effects of climate and human activities on fast ice dynamics in McMurdo Sound, Ross Sea, the sea and fast ice seasonal events (1978–2015), ice thicknesses and temperatures (1986–2014), wind velocities (1973–2015) and dates that an icebreaker annually opens a channel to McMurdo Station (1956–2015) are reported. A significant relationship exists between sea ice concentration and fast ice extent in the Sound. While fast/sea ice retreat dates have not changed, fast/sea ice reaches a minimum later and begins to advance earlier, in partial agreement with changes in Ross Sea regional pack ice dynamics. -

Piece for the Nimrod

“Antarctic Sites outside the Antarctic - Memorials, Statues, Houses, Graves and the occasional Pub” Presented at the 6th ‘Shackleton Autumn School’ Athy, Co, Kildare, Ireland, Sunday 29 October 2006 onument, Hamilton, Ohio. HE ANTARCTIC is very far from where I grew up and have spent most of T my years. As a town planner I saw little prospect of having a job that would take me there and I couldn’t afford paying money to get there. So I travelled to Antarctica in a vicarious way, collecting ‘sites’ of mainly historic interest with some association to the seventh continent but not actually there. My collection resides in what I call my “Low-Latitude Antarctic Gazetteer” and began close to forty years ago with its first entry, Captain Scott’s house at 56 Oakley Street in London (one of several associated with him but the only one bearing the coveted ‘blue plaque’). The number of entries now totals 887. Fully 144 of these relate to a greater or lesser degree to Sir Ernest Shackleton (Scott comes in second at 122, Amundsen 37). Herewith are some of my Shackleton favorites (and a few others, too): SOME HOUSES Shackleton houses abound. The first and most important is Kilkea House, not far from Athy, Co. Kildare, where Ernest was born on the morning of 15 February 1874. The house still stands in a lovely rural setting. But by 1880 the family had moved to Dublin to 35 Marlborough Road, an attractive brick row house south of the city center and one of three Shackleton houses commemorated with plaques, this particular one being unveiled on May 20, 2000. -

Santa Cruz Sentinel Columns by Gary Griggs, Director, Institute of Marine Sciences, UC Santa Cruz

Our Ocean Backyard –– Santa Cruz Sentinel columns by Gary Griggs, Director, Institute of Marine Sciences, UC Santa Cruz. #179 March 7, 2015 Shackleton’s Second Antarctic Expedition Ernest Shackleton’s first Antarctic expedition didn’t go well, and he privately vowed to return to the Antarctic and outdo Robert Scott. Following his return to England and a period of convalescence, he found himself in public demand as the first major figure to return from Antarctica because the ship Discovery was still lodged in the ice. He was offered a series of temporary positions advising and assisting other polar expeditions, and also worked briefly as a journalist. Because of his visibility and personal qualities, he was soon offered a job with a wealthy industrialist, which involved interviewing and entertaining his business associates. Shackleton’s highest priority, however, was mounting another expedition to Antarctica, with the goal of getting to both the geographical South Pole as well as the South Magnetic Pole, which don’t happen to be in the same location. His employer, William Beardmore, was impressed enough to offer some financial support. Obtaining funding for an expedition was challenging, but through his friends and connections he was able to obtain the last of the necessary funds just two weeks before the expedition ship, Nimrod, was ready to depart. While Nimrod may seem like an odd name for a ship, it was originally a biblical word meaning mighty hunter, appropriate for a ship. In modern times, however, it has been used to describe someone who is not particular bright, synonymous with words like moron, doofus, lamebrain or numbskull. -

Shackleton's Nimrod..M Riga? Was in the Russian Empire at the Time, but Most of the Trade Ian R

172 CORRESPONDENCE not forcing ice. However, it is a fact that any icebreaker wintered (1997-98) in the ice of the Beaufort and Chukchi navigator will always prefer to stay out of ice if at all seas — that the overall cover and thickness of drift ice in possible, even if the open-water route may be longer, as the Arctic Ocean is decreasing. However, the process is there is less effort required and lower potential for damage gradual, and the openings in the ice at the North Pole in the to the vessel. summer of 2000 are part of a perfectly natural phenomenon All of these factors add up to prove that nothing that has always occurred at irregular intervals, and may be startlingly new has taken place at the North Pole in the repeated at any time or may not occur again for many years. space of one year. It has already been established by As always, this will depend on the interaction between scientific observation — such as Operation Sheba, when wind and ice — and will have nothing to do with sudden the Canadian Coast Guard icebreaker des Groseilliers melting. Shackleton's Nimrod..M Riga? was in the Russian Empire at the time, but most of the trade Ian R. Stone of the Baltic provinces was in the hands of Baltic German Laggan Juys, Larivane Close, Andreas, merchants resident in those countries. This may be the IsleofManIM7 4HD reason why the script on the bell is not Cyrillic. Received December 2000 I also approached Dr A. Tatham, keeper at the Royal Geographical Society, and he was kind enough to conduct Readers of Polar Record will be aware of the superb a speedy search of the Society' s records. -

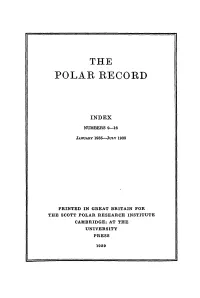

POL Volume 2 Issue 16 Back Matter

THE POLAR RECORD INDEX NUMBERS 9—16 JANUARY 1935—JULY 1938 PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN FOR THE SCOTT POLAR RESEARCH INSTITUTE CAMBRIDGE: AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS 1939 THE POLAR RECORD INDEX Nos. 9-16 JANUARY 1935—JULY 1938 The names of ships are in italics. Expedition titles are listed separately at Uie end Aagaard, Bjarne, II. 112 Alazei Mountains, 15. 5 Abruzzi, Duke of, 15. 2 Alazei Plateau, 12. 125 Adams, Cdr. .1. B., 9. 72 Alazei River, 14. 95, 15. 6 Adams, M. B., 16. 71 Albert I Peninsula, 13. 22 Adderley, J. A., 16. 97 Albert Harbour, 14. 136 Adelaer, Cape, 11. 32 Alberta, 9. 50 Adelaide Island, 11. 99, 12. 102, 103, 13. Aldan, 11. 7 84, 14. 147 Aldinger, Dr H., 12. 138 Adelaide Peninsula, 14. 139 Alert, 11. 3 Admiralty Inlet, 13. 49, 14. 134, 15. 38 Aleutian Islands, 9. 40-47, 11. 71, 12. Advent Bay, 10. 81, 82, 11. 18, 13. 21, 128, 13. 52, 53, 14. 173, 15. 49, 16. 15. 4, 16. 79, 81 118 Adytcha, River, 14. 109 Aleutian Mountains, 13. 53 Aegyr, 13. 30 Alexander, Cape, 11. GO, 15. 40 Aerial Surveys, see Flights Alexander I Land, 12. 103, KM, 13. 85, Aerodrome Bay, II. 59 80, 14. 147, 1-19-152 Aeroplanes, 9. 20-30, 04, (i5-(>8, 10. 102, Alcxamtrov, —, 13. 13 II. 60, 75, 79, 101, 12. 15«, 158, 13. Alexcyev, A. D., 9. 15, 14. 102, 15. Ki, 88, 14. 142, 158-103, 16. 92, 93, 94, 16. 92,93, see also unilcr Flights Alftiimyri, 15. -

Some Canadians in the Antarctic G

ARCTIC VOL. 39, NO. 4 (DECEMBER 1986)P. 368-369 Some Canadians in the Antarctic G. HATTERSLEY-SMITH’ (Received 18 February 1986; accepted in revised form Il Julv 1986) à nos jours. Mots clés: antarctique, expédition Traduit pour le journal par Nésida Loyer. As a country Canada has never been active in the Antarctic (except onthe one occasion mentioned atthe end of this note), but individual Canadians have made distinguished, in some cases heroic, contributions to Antarcticexploration andresearch. I have picked a number of such Canadians - the list is by no means exhaustive - who span the period from 1898 to the present time. Three of those chosen, although born inthe U.K., came to Canadaas young men andset forth on their expeditions from Canada; the rest were born in Canada. The Antarctic mainland was discoveredin 1820 in the north- ern part of what is now the British AntarcticTerritory. Sealers were active in this area in succeeding years, including New- foundland and Nova Scotia sealers in the period 1894-19 12. There were also several important exploratoryvoyages around other parts of the continent in the 19th century, but it was not until 1898 that an expedition wintered on the mainland. This was the Southern Cross Expedition, 1898-1900,to the Ross Sea area, and among those who wintered at Cape Adare was the expedition naturalist Hugh Blackwall Evans(1874-1975) (Fig. l), a pioneer in western Canada who had already taken parta in sealing expedition to Îles Kerguelen in1897-98. Following his return to Canada in 1901, he spentthe rest of his longlife on his farm near Vermilion, Alberta. -

Naming Antarctica

NASA Satellite map of Antarctica, 2006 - the world’s fifth largest continent Map of Antarctica, Courtesy of NASA, USA showing key UK and US research bases Courtesy of British Antarctic Survey Antarctica Naming Antarctica A belief in the existence of a vast unknown land in the far south of the globe dates The ancient Greeks knew about the Arctic landmass to The naming could be inspired by other members of the back almost 2500 years. The ancient Greeks called it Ant Arktos . The Europeans called the North. They named it Arktos - after the ‘Great Bear’ expedition party, or might simply be based on similarities it Terra Australis . star constellation. They believed it must be balanced with homeland features and locations. Further inspiration by an equally large Southern landmass - opposite the came from expressing the mood, feeling or function of The Antarctic mainland was first reported to have been sighted in around 1820. ‘Bear’ - the Ant Arktos . The newly identified continent a place - giving names like Inexpressible Island, During the 1840s, separate British, French and American expeditions sailed along the was first described as Antarctica in 1890. Desolation Island, Arrival Heights and Observation Hill. continuous coastline and proved it was a continent. Antarctica had no indigenous population and when explorers first reached the continent there were no The landmass of Antarctica totals 14 million square kilometres (nearly 5.5 million sq. miles) place names. Locations and geographical features - about sixty times bigger than Great Britain and almost one and a half times bigger than were given unique and distinctive names as they were the USA.