The Siege and Storming of Leicester May 1645 Jeff Richards New

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Contemporary Map of the Defences of Oxford in 1644

A Contemporary Map of the Defences of Oxford in 1644 By R. T. LATTEY, E. J. S. PARSONS AND I. G. PHILIP HE student of the history of Oxford during the Civil War has always been T handicapped in dealing with the fortifications of the City, by the lack of any good contemporary map or plan. Only two plans purporting to show the lines constructed during the years 1642- 6 were known. The first of these (FIG. 24), a copper-engraving in the 'Wood collection,! is sketchy and ill-drawn, and half the map is upside-down. The second (FIG. 25) is in the Latin edition of Wood's History and Antiquities of the University of Oxford, published in 1674,2 and bears the title' Ichnographia Oxonire una cum Propugnaculis et Munimentis quibus cingebatur Aimo 1648.' The authorship of this plan has been attributed both to Richard Rallingson3 and to Henry Sherburne.' We know that Richard Rallingson drew a' scheme or plot' of the fortifications early in 1643,5 and Wood in his Athenae Oxomenses 6 states that Henry Sherburne drew' an exact ichno graphy of the city of Oxon, while it was a garrison for his Majesty, with all the fortifications, trenches, bastions, etc., performed for the use of Sir Thomas Glemham 7 the governor thereof, who shewing it to the King, he approved much of it, and wrot in it the names of the bastions with his own hand. This ichnography, or another drawn by Richard Rallingson, was by the care of Dr. John Fell engraven on a copper plate and printed, purposely to he remitted into Hist. -

Cromwelliana 1993

Cromwelliana 1993 The Cromwell Association The Cromwell Association CROMWELLIANA 1993 President: Dr JOHN MORRILL, DPhil, FRHistS Vice Presidents: Baron FOOT of Buckland Monachorurn Right Hon MICHAEL FOOT, PC edited by Peter Gaunt Dr MAURICE ASHLEY, CBE, DPhil, DLitt Professor IV AN ROOTS, MA, FSA, FRHistS ********** Professor AUSTIN WOOLRYCH, MA, DLitt. FBA Dr GERALD AYLMER, MA, DPhil, FBA, FRHistS CONTENTS Miss HILARY PLAIT, BA Mr TREWIN COPPLESTONE, FRGS Chairman: Dr PEfER GAUNT, PhD, FRHistS Cromwell Day 1992. Oliver Cromwell and the Godly Reformation. By Dr Barry Coward. 2 Honorary Secretary: Miss PAT BARNES Cosswell Cottage, Northedge, Tupton, Chesterfield, S42 6A Y Oliver Cromwell and the Battle of Gainsborough, Honorary Treasurer. Mr JOHN WESTMACOIT July 1643. By John West. 9 1 Salisbury Close, Wokingham, Berkshire, RGI l 4AJ Oliver Cromwell and the English Experience of Manreuvre THE CROMWELL ASSOCIATION was founded in 1935 by the late Rt Hon Isaac Foot Warfare 1645-1651. Part One. By Jonathan R Moore. 15 and others to commemorate Oliver Cromwell, the great Puritan stateman, and to encourage the study of the history of his times, his achievements and influence. It is The Diagnosis of Oliver Cromwell's Fatal Illness. neither political nor sectarian, its aims being essentially historical. The Association By Dr C H Davidson. 27 seeks to advance its aims in a variety of ways which have included: a. the erection of commemorative tablets (e.g. at Naseby, Dunbar, Worcester, Revolution and Restoration: The Effect on the Lives of Preston, etc) (From time to time appeals are made for funds to pay for projects of Ordinary Women. -

Treatment of Prisoners of War in England During the English Civil Wars, 22 August, 1642 - 30 January, 1648/49

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1968 Treatment of prisoners of war in England during the English Civil Wars, 22 August, 1642 - 30 January, 1648/49 Gary Tristram Cummins The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Cummins, Gary Tristram, "Treatment of prisoners of war in England during the English Civil Wars, 22 August, 1642 - 30 January, 1648/49" (1968). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 3948. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/3948 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TRBATJ^MT OF PRISONERS OF WAR IN EM6LAND 0URIM6 THE ENGLISH CIVIL WARS 22 AUGUST 1642 - 30 JANUARY 1648/49 by ISARY TRISTRAM C»#IIN8 i.A, University oi Mmtam, 1964 Presented In partial fulftll»©nt of th« requirements for the d®gr®e of Master of Arts University of Montana 19fi8 Approved: .^.4.,.3dAAsdag!Ac. '»€&iat« December 12, 1968 Dste UMI Number EP34264 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk i ii UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF LAW, ARTS & SOCIAL SCIENCES SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES Doctor of Philosophy MILITARY INTELLIGENCE OPERATIONS IN THE FIRST ENGLISH CIVIL WAR 1642 – 1646 By John Edward Kirkham Ellis This thesis sets out to correct the current widely held perception that military intelligence operations played a minor part in determining the outcome of the English Civil War. In spite of the warnings of Sir Charles Firth and, more recently, Ronald Hutton, many historical assessments of the role played by intelligence-gathering continue to rely upon the pronouncements made by the great Royalist historian Sir Edward Hyde, earl of Clarendon, in his History of the Rebellion. Yet the overwhelming evidence of the contemporary sources shows clearly that intelligence information did, in fact, play a major part in deciding the outcome of the key battles that determined the outcome of the Civil War itself. -

And Nottingham in the English Civil War, 1643

Issue 01, June 2015 HIDDEN VOICES Inside this issue Holding the centre ground Special Civil War issue The strategic importance of the 4 North Midlands from 1642 - 1646 Hidden voices Newark and the civilian experience 12 of the British Civil Wars Treachery and conspiracy Nottinghamshire during the 21 English Civil War 1 PLUS A brief guide to the Civil War • Introducing the National Civil War Centre, Newark • Regional news & events and much more Visit www.eastmidlandshistory.org.uk or email [email protected] WELCOME & CONTENTS WELCOME HIDDEN VOICES Welcome to East Midlands History and Heritage, Contents the magazine that uniquely WELCOME & CONTENTS WELCOME So write Studying History caters for local history societies, schools and colleges, Holding the centre ground: the strategic importance of for us and Heritage at NTU heritage practitioners and 04 the North Midlands history professionals across 1642 - 1646 Let us have details of your news MA History: Teaching directly reflects the internationally recognised expertise of our staff in and events. medieval and early modern British and European history, modern and contemporary history, the region, putting them public history and global history. Case studies include: Crusades and Crusaders; Early Modern We’ll take your stories about your Religions and Cultures; Slavery, Race and Lynching; Memory, Genocide, Holocaust; Social History in contact with you and community’s history to a larger regional and ‘The Spatial Turn’. The course combines the coherence and support of a taught MA with the Introducing the National audience. We’d also welcome articles challenges of a research degree. you with them. Civil War Centre, Newark about our region’s past. -

The Metrology of the English Civil War Coinages of Charles I

THE METROLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR COINAGES OF CHARLES I EDWARD BESLY and MICHAEL COWELL ONE aspect of the coinages of the English Civil War of 1642-9 which nas never been systematically assessed is the extent to which the apparently largely inexperienced persons who produced many of them succeeded in providing what was required: coin of the realm of full weight and metallic standard. To one writer '. notwithstanding the King's distress for money, it is remarkable, he never debased the coin, or raised the value of it'; to another 'the poor representation of Charles's provincial coins has long been recognised as characteristic of Civil War hoards, and it may be that some of them laboured under a not unjustified suspicion of being slightly base'.1 To some extent, the relative rarity of royalist issues may now be seen as a function of small original output, but there are coins whose appearance is unprepossessing, whether in shape, design or metal. As part of a wider project on the Civil War issues,2 built initially on hoard evidence, the opportunity has been taken to examine various technical elements of minting in England at this time. This paper presents the results of a series of analyses of royalist and other coinages and a survey of the weights of surviving specimens. Minting technology itself has been discussed elsewhere and will not be dealt with here, nor will judgement be attempted on the artistic or other abilities of the engravers involved.3 Early in the seventeenth century, all English minting in precious metals took place at the Tower of London, a monopoly broken only in 1637 with the establishment of a small branch mint at Aberystwyth for the coining of newly-refined Welsh silver. -

1600S in Marston

1600s in Marston Below are documents showing life in Marston in the 1600s. The Manor House The earliest history of the house now known as the Manor House is quite uncertain, but at least one book speaks of its 16th century character. This would have described the one house which is now in two — the Manor House and Cromwell’s House. What seems definite is that, in the times of James I, a young man called Unton Croke came down from his family home at Studley Priory and married a Marston heiress. He made her house “grander”, although a later writer called it “a heavy stone building, erected without much attention to elegance or regularity”. Croke was shrewd enough to support the Parliamentary cause during the Civil War, so that his house was the headquarters of General Fairfax during the siege of Oxford, was visited by Oliver Cromwell, and may have been used for the signing of the treaty following the siege. Unkton Croke was a lawyer and seems to have prospered during the Protectorate to such an extent that, after the Restoration, he was obliged, and able, to put up a bond of £4000 for the good behaviour of his Round-head son. If you look at the memorial to father and son on the northern side of the chancel in the church, you will see the change in fortune between the two generations. The Croke family interest had ended by 1690, when the house was lived in by Thomas Rowney, another wealthy lawyer who, early in the 18th century, gave the land for the building of the Radcliffe Infirmary. -

TACW Playbook-3

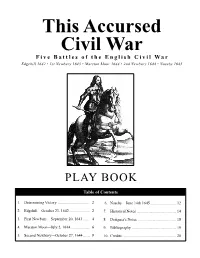

This Accursed Civil War 1 This Accursed Civil War Five Battles of the English Civil War Edgehill 1642 • 1st Newbury 1643 • Marston Moor 1644 • 2nd Newbury 1644 • Naseby 1645 PLAY BOOK Table of Contents 1. Determining Victory ................................. 2 6. Naseby—June 14th 1645 .......................... 12 2. Edgehill—October 23, 1642 ..................... 2 7. Historical Notes ........................................ 14 3. First Newbury—September 20, 1643 ....... 4 8. Designer's Notes ....................................... 18 4. Marston Moor—July 2, 1644.................... 6 9. Bibliography ............................................. 19 5. Second Newbury—October 27, 1644 ....... 8 10. Credits ....................................................... 20 © 2002 GMT Games 2 This Accursed Civil War Determining Victory Parliament. The King had a clear advantage in numbers and quality of horse. The reverse was the case for Parliament. This Royalists earn VPs for Parliament losses and vice versa. Vic- pattern would continue for some time. tory is determined by subtracting the Royalist VP total from the Parliament VP total. The Victory Points (VPs) are calculated Prelude for the following items: Charles I had raised his standard in Nottingham on August 22nd. Victory The King found his support in the North, Wales and Cornwall; Event Points the Parliament in the South and East. The army of Parliament Eliminated Cavalry Unit ............................................. 10 was at Northampton. The King struck out towards Shrewsbury to gain needed support. Essex moved on Worcester, trying to Per Cavalry Casualty Point place his army between the King and London, as the King's on Map at End ............................................................. 2 army grew at Shrewsbury. By the 12th of October the King felt Eliminated Two-Hex Infantry Unit ............................. 10 he was sufficiently strong to move on London and crush the Eliminated One-Hex Heavy Infantry Unit ................. -

Oxford Army List for 1642-1646

Oxford Army List for 1642-1646 By F. J. VARLEY HIS is an attempt to collect as many names as possible of the officers who are known to have served in Oxford with the regular garrison or the T auxiliary regiments during the period of the Royalist occupation. No complete list is in existence, and any list must be compiled from such material as exists in burial-registers, monumental inscriptions, dispatches, orders, news sheets, diaries, and miscellaneous references in printed or !\'lS. authorities noted in my The Siege of O:iford and supplement.' I have excluded, as far as possible, officers of the various field armies who visited Oxford from time to time, but I have not attempted to ascertain whether any of the large number who died and were buried in Oxford may not have belonged to other armies, an almost impossible task, and have a sumed that they all belonged to the regular garrison. There are many names in the list about which little, if anything, is known. I bave attempted to give a brief account of those officers who figured in the siege or in the operations and skirmishes around Oxford, or in the various relief-expeditions which were dispatched from Oxford. An asterisk is placed against the name of an officer who died, and the place of burial, where known, is added. For the sake of brevity I have not given the date of burial, etc., as these can be recovered from the registers. Officers of the auxiliary regiments are indicated by the letter A before their names. -

Sir Samuel Luke

Oxfordshire Record Society JOURNAL OF SIR SAMUEL LUKE Scoutmaster to the Earl Of Essex 1642 – 1644 Transcribed and Edited with an Introduction by I. G. Philip M.A. Secretary of the Bodleian Library Oxford JOURNAL OF SIR SAMUEL LUKE ii JOURNAL OF SIR SAMUEL LUKE This paper was originally published in 3 parts by the Oxfordshire Record Society between 1950 and 1953 Sir Samuel Luke, eldest son of Sir Oliver Luke, of Woodend, Bedfordshire, is probably best known as the supposed original of Butler's Hudibras, and is referred to in the key to Hudibras attributed to Roger L'Estrange as "a self-conceited commander under Oliver Cromwell" But Luke, whose reputation has suffered from this attribution, was neither a foolish nor an ineffectual figure.1 He represented Bedford borough in the Short Parliament of 1640 and in the Long Parliament, and then when Civil War broke out, as a member of the Presbyterian party, he joined the Parliamentary forces. From 30th July 1642 he was captain of a troop of horse and fought with his troop at Edgehill. Then on 4th January 1643 he was commissioned by the Earl of Essex to raise a troop of dragoons in Bedfordshire. With this troop Luke accompanied Essex from Windsor to Reading, was present at the siege of Reading, 15th-25th April,2 and then moved to the region of Thame where Essex established his headquarters in June. Here, at Chinnor, on 18th June Luke's troop was routed by Prince Rupert, but Luke himself, who was absent from the Chinnor fight, fought with Hampden at Chalgrove field on the same day, and distinguished himself by his courage. -

Coquet Island 1

Northamptonshire 114 NOR1~AMPTON modern - the restoration work to the Great S for Parlia- Hall, the east and west ranges, Walker's House NORTHUMBERLAND Northampton (SP7S~O~ ecur~e county town and the Laundry - and modern - the square ment throughout the Civil :a~~us and rallying south tower, the roof and most of the interior. The county was held for the King without challen . occurred tn January and February 1644 as t ge 1642-43 and the fir . frequently served asdah~en ezy at Northampton The castle is open on Sundays and certain du~ing point. Essex gathere is ~rm robably here throwing back the Earl of Newcastle's arm dh e Scottish Parliamentarians sthreal fighting · s tember 1642 and it was P . · weekdays during the summer. their departure southwards in March the /,an. capturing most of the stronghoWrc ed through, ~~at etromwell and the Cambridgeshi[e ~;;;d encouraged by the short-lived presence ofnfvr. s cause in Northumberland made ~ [.;;_route. \'\'1th cnt 101ncd him. Cromwell cert~1n y . Titch.marsh (U02t800 ~ Sir Gilb~rt Pickering, compatriots reappeared after Marston Moor ondtroRse's l~co ttish Royalists. Their Pa1efl.recovery, ~1rough the rown on several oc<..as1ons later in a close associate and distant relanve of Oliver an oya ism · N h r 1ame11tary ende . romwe II passed t h rough the county in d in ort untberland was 11 . / Cromwell was born, brought up and lived at d C 1648 an 1650-51 on h. e,,ect1ve y the "·ar. M rs way to and from Scotland. The only real fighting here took place in ~y the late Tudor manor house in Titchmarsh. -

HISTORY of ENGLAND, Week 25 Civil War

HISTORY OF ENGLAND, Week 25 Civil War Institute for the Study of Western Civilization SaturdayMay 9, 2020 King Charles I 1600-1649 SaturdayMay 9, 2020 2003 SaturdayMay 9, 2020 to kill a king trailer SaturdayMay 9, 2020 King Charles I 1600-1649 SaturdayMay 9, 2020 THE FATHER James Stuart King James I King: 1603-1625 SaturdayMay 9, 2020 What did father teach son about politics? SaturdayMay 9, 2020 Basilikon Doron Royal Gift Theory of monarchy 1598 The True Law of Free Monarchies. In 1597–98, James wrote The True Law of Free Monarchies and Basilikon Doron (Royal Gift), in which he argues a theological basis for monarchy. In the True Law, he sets out the divine right of kings, explaining that kings are higher beings than other men for Biblical reasons, though "the highest bench is the sliddriest to sit upon".[59] The document proposes an absolutist theory of monarchy, by which a king may impose new laws by royal WHAT prerogative but must also pay heed to JAMES tradition and to God, who would "stirre up such scourges as pleaseth him, for TAUGHT punishment of wicked kings".[60] CHARLES SaturdayMay 9, 2020 Basilikon Doron Theory of monarchy Royal Gift The True Law of Free Monarchies. 1598 In 1597–98, Basilikon Doron was written as a book of instruction for four-year-old Prince Henry and provides a more practical guide to kingship. The work is considered to be well written and perhaps the best example of James's prose. James's advice concerning parliaments, which he understood as merely the king's "head court", foreshadows his difficulties with the English Commons: "Hold no Parliaments," he tells Henry, "but for the necesitie of new Lawes, which would be but seldome".