Proximal Biceps Tendon and Rotator Cuff Tears

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rotator Cuff and Subacromial Impingement Syndrome: Anatomy, Etiology, Screening, and Treatment

Rotator Cuff and Subacromial Impingement Syndrome: Anatomy, Etiology, Screening, and Treatment The glenohumeral joint is the most mobile joint in the human body, but this same characteristic also makes it the least stable joint.1-3 The rotator cuff is a group of muscles that are important in supporting the glenohumeral joint, essential in almost every type of shoulder movement.4 These muscles maintain dynamic joint stability which not only avoids mechanical obstruction but also increases the functional range of motion at the joint.1,2 However, dysfunction of these stabilizers often leads to a complex pattern of degeneration, rotator cuff tear arthropathy that often involves subacromial impingement.2,22 Rotator cuff tear arthropathy is strikingly prevalent and is the most common cause of shoulder pain and dysfunction.3,4 It appears to be age-dependent, affecting 9.7% of patients aged 20 years and younger and increasing to 62% of patients of 80 years and older ( P < .001); odds ratio, 15; 95% CI, 9.6-24; P < .001.4 Etiology for rotator cuff pathology varies but rotator cuff tears and tendinopathy are most common in athletes and the elderly.12 It can be the result of a traumatic event or activity-based deterioration such as from excessive use of arms overhead, but some argue that deterioration of these stabilizers is part of the natural aging process given the trend of increased deterioration even in individuals who do not regularly perform overhead activities.2,4 The factors affecting the rotator cuff and subsequent treatment are wide-ranging. The major objectives of this exposition are to describe rotator cuff anatomy, biomechanics, and subacromial impingement; expound upon diagnosis and assessment; and discuss surgical and conservative interventions. -

Monday: Back, Biceps, Forearms, Traps & Abs Wednesday

THE TOOLS YOU NEED TO BUILD THE BODY YOU WANT® Store Workouts Diet Plans Expert Guides Videos Tools BULLDOZER TRAINING 3 DAY WORKOUT SPLIT 3 day Bulldozer Training muscle building split. Combines rest-pause sets with progressive Main Goal: Build Muscle Time Per Workout: 30-45 Mins resistance. Workouts are shorter but more Training Level: Intermediate Equipment: Barbell, Bodyweight, intense. Program Duration: 8 Weeks Dumbbells, EZ Bar, Machines Link to Workout: https://www.muscleandstrength.com/ Days Per Week: 3 Days Author: Steve Shaw workouts/bulldozer-training-3-day-workout-split Monday: Back, Biceps, Forearms, Traps & Abs Exercise Mini Sets Rep Goal Rest Deadlift: Perform as many rest-paused singles as you (safely) can within 10 Mins. Use a weight you could easily perform a 10 rep set with. Rest as needed. When you can perform 15 reps, add weight the next time you deadlift. Barbell Row 5 25 30 / 30 / 45 / 45 Wide Grip Pull Up 5 35 30 / 30 / 30 / 30 Standing Dumbbell Curl 4 25 30 / 30 / 30 EZ Bar Preacher Curl 4 25 30 / 30 / 30 Seated Barbell Wrist Curl 4 35 30 / 30 / 30 Barbell Shrug 5 35 30 / 30 / 30 / 30 Preferred Abs Exercise(s): I recommend using at least one weighted exercise (e.g. Weighted Sit Ups or Cable Crunches). Rest Periods: 30 / 30 / 45 / 45 notates rest periods between each set. Take 30 Secs after the 1st set, 30 Secs after the 2nd set, 45 Secs after the 3rd set, etc. After the final set, rest, and move on to the next exercise. -

Musculoskeletal Diagnostic Imaging

Musculoskeletal Diagnostic Imaging Vivek Kalia, MD MPH October 02, 2019 Course: Sports Medicine for the Primary Care Physician Department of Radiology University of Michigan @VivekKaliaMD [email protected] Objectives • To review anatomy of joints which commonly present for evaluation in the primary care setting • To review basic clinical features of particular musculoskeletal conditions affecting these joints • To review key imaging features of particular musculoskeletal conditions affecting these joints Outline • Joints – Shoulder – Hip • Rotator Cuff Tendinosis / • Osteoarthritis Tendinitis • (Greater) Trochanteric bursitis • Rotator Cuff Tears • Hip Abductor (Gluteal Tendon) • Adhesive Capsulitis (Frozen Tears Shoulder) • Hamstrings Tendinosis / Tears – Elbow – Knee • Lateral Epicondylitis • Osteoarthritis • Medical Epicondylitis • Popliteal / Baker’s cyst – Hand/Wrist • Meniscus Tear • Rheumatoid Arthritis • Ligament Tear • Osteoarthritis • Cartilage Wear Outline • Joints – Ankle/Foot • Osteoarthritis • Plantar Fasciitis • Spine – Degenerative Disc Disease – Wedge Compression Deformity / Fracture Shoulder Shoulder Rotator Cuff Tendinosis / Tendinitis • Rotator cuff comprised of 4 muscles/tendons: – Supraspinatus – Infraspinatus – Teres minor – Subscapularis • Theory of rotator cuff degeneration / tearing with time: – Degenerative partial-thickness tears allow superior migration of the humeral head in turn causes abrasion of the rotator cuff tendons against the undersurface of the acromion full-thickness tears may progress to -

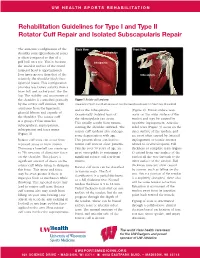

Rehabilitation Guidelines for Type I and Type II Rotator Cuff Repair and Isolated Subscapularis Repair

UW HEALTH SPORTS REHABILITATION Rehabilitation Guidelines for Type I and Type II Rotator Cuff Repair and Isolated Subscapularis Repair The anatomic configuration of the Back View Front View shoulder joint (glenohumeral joint) Supraspinatus is often compared to that of a golf ball on a tee. This is because Infraspinatus the articular surface of the round humeral head is approximately Teres four times greater than that of the Minor Subscapularis relatively flat shoulder blade face (glenoid fossa). This configuration provides less boney stability than a truer ball and socket joint, like the hip. The stability and movement of the shoulder is controlled primarily Figure 1 Rotator cuff anatomy by the rotator cuff muscles, with Image property of Primal Pictures, Ltd., primalpictures.com. Use of this image without authorization from Primal Pictures, Ltd. is prohibited. assistance from the ligaments, and/or the infraspinatus. (Figure 2). Bursal surface tears glenoid labrum and capsule of Occasionally isolated tears of occur on the outer surface of the the shoulder. The rotator cuff the subscapularis can occur. tendon and may be caused by is a group of four muscles: This usually results from trauma repetitive impingement. Articular subscapularis, supraspinatus, rotating the shoulder outward. The sided tears (Figure 3) occur on the infraspinatus and teres minor rotator cuff tendons also undergo inner surface of the tendon, and (Figure 1). some degeneration with age. are most often caused by internal Rotator cuff tears can occur from This process alone can lead to impingement or tensile stresses repeated stress or from trauma. rotator cuff tears in older patients. related to overhead sports. -

Arterial Supply to the Rotator Cuff Muscles

Int. J. Morphol., 32(1):136-140, 2014. Arterial Supply to the Rotator Cuff Muscles Suministro Arterial de los Músculos del Manguito Rotador N. Naidoo*; L. Lazarus*; B. Z. De Gama*; N. O. Ajayi* & K. S. Satyapal* NAIDOO, N.; LAZARUS, L.; DE GAMA, B. Z.; AJAYI, N. O. & SATYAPAL, K. S. Arterial supply to the rotator cuff muscles.Int. J. Morphol., 32(1):136-140, 2014. SUMMARY: The arterial supply to the rotator cuff muscles is generally provided by the subscapular, circumflex scapular, posterior circumflex humeral and suprascapular arteries. This study involved the bilateral dissection of the scapulohumeral region of 31 adult and 19 fetal cadaveric specimens. The subscapularis muscle was supplied by the subscapular, suprascapular and circumflex scapular arteries. The supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles were supplied by the suprascapular artery. The infraspinatus and teres minor muscles were found to be supplied by the circumflex scapular artery. In addition to the branches of these parent arteries, the rotator cuff muscles were found to be supplied by the dorsal scapular, lateral thoracic, thoracodorsal and posterior circumflex humeral arteries. The variations in the arterial supply to the rotator cuff muscles recorded in this study are unique and were not described in the literature reviewed. Due to the increased frequency of operative procedures in the scapulohumeral region, the knowledge of variations in the arterial supply to the rotator cuff muscles may be of practical importance to surgeons and radiologists. KEY WORDS: Arterial supply; Variations; Rotator cuff muscles; Parent arteries. INTRODUCTION (Abrassart et al.). In addition, the muscular parts of infraspinatus and teres minor muscles were supplied by the circumflex scapular artery while the tendinous parts of these The rotator cuff is a musculotendionous cuff formed muscles received branches from the posterior circumflex by the fusion of the tendons of four muscles – viz. -

Primary and Secondary Consequences of Rotator Cuff

Hafizur Rahman Department of Mechanical Science and Engineering, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL 61801 Primary and Secondary e-mail: [email protected] Consequences of Rotator Cuff Eric Currier Department of Mechanical Science and Engineering, Injury on Joint Stabilizing University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL 61801 Tissues in the Shoulder e-mail: [email protected] Rotator cuff tears (RCTs) are one of the primary causes of shoulder pain and dysfunction Marshall Johnson in the upper extremity accounting over 4.5 million physician visits per year with 250,000 Department of Mechanical Engineering, rotator cuff repairs being performed annually in the U.S. While the tear is often consid- Georgia Institute of Technology, ered an injury to a specific tendon/tendons and consequently treated as such, there are Atlanta, GA 30332 secondary effects of RCTs that may have significant consequences for shoulder function. e-mail: [email protected] Specifically, RCTs have been shown to affect the joint cartilage, bone, the ligaments, as well as the remaining intact tendons of the shoulder joint. Injuries associated with the Rick Goding upper extremities account for the largest percent of workplace injuries. Unfortunately, Department of Orthopaedic, the variable success rate related to RCTs motivates the need for a better understanding Joint Preservation Institute of Iowa, of the biomechanical consequences associated with the shoulder injuries. Understanding West Des Moines, IA 50266 the timing of the injury and the secondary anatomic consequences that are likely to have e-mail: [email protected] occurred are also of great importance in treatment planning because the approach to the treatment algorithm is influenced by the functional and anatomic state of the rotator cuff Amy Wagoner Johnson and the shoulder complex in general. -

Impingement Syndrome and Tears of the Rotator Cuff

Impingement Syndrome and Tears of the Rotator Cuff Dr Keith Holt Impingement is a very common problem in which the tendons of the rotator cuff (predominantly supraspinatus) rub on the underside of the acromion (the bone at the point of the shoulder). This causes pain due to the repeated rubbing of those tendons and it is especially bad with certain positions of the arm. In particular it is difficult to put the arm behind the back and to use it in the elevated position. This makes it difficult to drive, change gears, hang clothes, comb one’s hair, and even to lie on the affected shoulder. The cause of this problem can be: How does the shoulder work? The shoulder, like the hip, is a ball and socket joint (like a tow 1) A muscle imbalance problem due to poor functioning bar). Unlike the hip however, the socket is very small and is of the rotator cuff tendons themselves; thus allowing the not big enough to hold the head of the humerus (the ball) arm to ride up and rub on the acromion, squashing the in place. This gives the joint a large range of motion but, as rotator cuff tendons in the process: or a consequence, it also means that it is potentially unstable. 2) A mechanical problem where the space for the tendon To function normally, muscles on both sides of the joint must is inadequate. One way this can occur is with an injury work together to hold the joint in place during movement. to the tendon itself which causes swelling of that tendon This means that when the deltoid muscle (see diagrams) lifts such that it becomes too large for the space at hand the arm out from the side of the body, the supraspinatus and [primary tendonitis (inflammation of the tendon) with other muscles of the rotator cuff must pull down on the top secondary impingement [rubbing of the tendon on the of the humerus. -

Rotator Cuff Tears

OrthoInfo Basics Rotator Cuff Tears What is a rotator cuff? One of the Your rotator cuff helps you lift your arm, rotate it, and reach up over your head. most common middle-age It is made up of muscles and tendons in your shoulder. These struc- tures cover the head of your upper arm bone (humerus). This “cuff” complaints is holds the upper arm bone in the shoulder socket. shoulder pain. Rotator cuff tears come in all shapes and sizes. They typically occur A frequent in the tendon. source of that Partial tears. Many tears do not completely sever the soft tissue. Full thickness tears. A full or "complete" tear will split the soft pain is a torn tissue into two, sometimes detaching the tendon from the bone. rotator cuff. Rotator Cuff Bursa A torn rotator cuff will Tendon Clavicle (Collarbone) Humerus weaken your shoulder. (Upper Arm) This means that many Normal shoulder anatomy. daily activities, like combing your hair or Scapula getting dressed, may (Shoulder Blade) become painful and difficult to do. Rotator Cuff Tendon A complete tear of the rotator cuff tendon. 1 OrthoInfo Basics — Rotator Cuff Tears What causes rotator cuff tears? There are two main causes of rotator cuff repeating the same shoulder motions again and tears: injury and wear. again. Injury. If you fall down on your outstretched This explains why rotator cuff tears are most arm or lift something too heavy with a jerking common in people over 40 who participate in motion, you could tear your rotator cuff. This activities that have repetitive overhead type of tear can occur with other shoulder motions. -

Rotator Cuff 101 Every Year, More Than Two Million American Adults Seek Medical Care for Rotator Cuff Disease

BONE & JOINT BRIEFINGS Rotator Cuff 101 Every year, more than two million American adults seek medical care for rotator cuff disease. he rotator cuff is a series of 4 muscles It’s important to recognize that most people who surrounding the ball and socket joint of have shoulder pain don’t have a rotator cuff tear; the shoulder and plays a crucial role in there are many other causes. Pain from a rotator cuff optimizing shoulder function. The shoulder tear is usually experienced on the lateral aspect of the joint is inherently unstable, as the major arm, almost midway between the shoulder and the Tmuscles that move the shoulder around—the deltoid, elbow. It’s usually worse with overhead activity and the pectoralis, the back muscles—have a tendency worse at night. If this sort of pain is accompanied by to move the ball out of the center of the socket. The weakness, it probably should be checked right away. rotator cuff, almost as a counterforce against the If there’s no weakness involved, just aches and major muscles, helps to provide a stable fulcrum and pain, then ice, anti-inflammatory medication and a to optimize shoulder mechanics. couple of weeks of lighter activity could be all one As you might imagine, the muscles of the rotator needs. However, if the pain continues for more than a Christopher Gorczynski, MD cuff are subjected to quite a bit of stress. Friction couple of weeks, it deserves to be evaluated. Because and heavy usage (through sports or other repetitive the rotator cuff is under tension, tears generally get activity) can cause the tendons of the rotator cuff bigger over time and partial tears can become full- Those of us who are 30, to thicken or become inflamed and get “pinched” thickness tears. -

Pronator Teres Tear at the Myotendinous Junction in the Recreational Golfer: a Case Report

International Journal of Orthopaedics Online Submissions: http: //www.ghrnet.org/index.php/ijo Int. J. of Orth. 2021 April 28; 8(2): 1457-1462 doi: 10.17554/j.issn.2311-5106.2021.08.405 ISSN 2311-5106 (Print), ISSN 2313-1462 (Online) CASE REPORT Pronator Teres Tear at the Myotendinous Junction in the Recreational Golfer: A Case Report Alvarho J. Guzman1, BA; Stewart A. Bryant1, MD; Shane M. Rayos Del Sol1, BS, MS; Brandon Gardner1, MD, PhD; Moyukh O. Chakrabarti1, MBBS; Patrick J. McGahan1, MD; James L. Chen1, MD 1 Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Advanced Orthopedics & was expected to make a complete return to pre-injury level athletic Sports Medicine, San Francisco, CA, the United States. activity with conservative management. With this article, we consider biceps rupture on the differential diagnoses associated with pronator Conflict-of-interest statement: The author(s) declare(s) that there teres musculotendinous injuries, emphasize the significance of club is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper. type in relation to golfing injuries, and propose a potential pronator teres rupture non-operative rehabilitation protocol. Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external Key words: Pronator teres; Golf; Biceps; Ecchymosis; Rehabilitation reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Com- protocol mons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non- © 2021 The Author(s). Published by ACT Publishing Group Ltd. All commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, rights reserved. -

Guidelines for Returning to Weightlifting Following Shoulder Surgery

Guidelines for Returning to Weightlifting Following Shoulder Surgery Before initiating any type of weight training, you must have full range of motion of the shoulder and normal strength of the rotator cuff and scapular muscle groups. Your motion and strength should be tested by COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY your surgeon before beginning any weightlifting regimen. CENTER FOR SHOULDER, ELBOW AND SPORTS The following illustrates the approximate time table for beginning MEDICINE weight training following your particular surgery: Rotator Cuff Repair: 6 months Christopher S. Ahmad, MD Bankart Repair: 3 months Office (212) 305-5561 Labrum Repair: 4-6 months Fax (212) 305-4040 Arthroscopic Subacromial Decompression: 4-6 months Louis U. Bigliani, MD When beginning a weight training program, you should start with low Office (212) 305-5564 weights and with 3 sets of 15-20 repetitions. The high repetition sets Fax (212) 305-0999 will ensure that the weights you are using are not too heavy. NEVER perform any weightlifting exercise to the point of muscle failure. Edwin Cadet, MD Muscle failure occurs when the muscle is no longer able to provide the Office (212) 305-4626 energy necessary to contract and move the joints involved in the Fax (212) 305-4040 particular exercise. When muscle failure occurs, the risk for joint, muscle and tendon injuries is greatly increased. William N. Levine, MD Office (212) 305-0762 Exercises to AVOID: Fax (212) 305-4040 1. Triceps Dips 2. Chest Flies Appointment Scheduling 3. Pull-downs behind the neck (212) 305-4565 4. Wide grip bench press 5. Triceps press overhead Mailing Address: th 6. -

Chapter 5 the Shoulder Joint

The Shoulder Joint • Shoulder joint is attached to axial skeleton via the clavicle at SC joint • Scapula movement usually occurs with movement of humerus Chapter 5 – Humeral flexion & abduction require scapula The Shoulder Joint elevation, rotation upward, & abduction – Humeral adduction & extension results in scapula depression, rotation downward, & adduction Manual of Structural Kinesiology – Scapula abduction occurs with humeral internal R.T. Floyd, EdD, ATC, CSCS rotation & horizontal adduction – Scapula adduction occurs with humeral external rotation & horizontal abduction © McGraw-Hill Higher Education. All rights reserved. 5-1 © McGraw-Hill Higher Education. All rights reserved. 5-2 The Shoulder Joint Bones • Wide range of motion of the shoulder joint in • Scapula, clavicle, & humerus serve as many different planes requires a significant attachments for shoulder joint muscles amount of laxity – Scapular landmarks • Common to have instability problems • supraspinatus fossa – Rotator cuff impingement • infraspinatus fossa – Subluxations & dislocations • subscapular fossa • spine of the scapula • The price of mobility is reduced stability • glenoid cavity • The more mobile a joint is, the less stable it • coracoid process is & the more stable it is, the less mobile • acromion process • inferior angle © McGraw-Hill Higher Education. All rights reserved. 5-3 © McGraw-Hill Higher Education. All rights reserved. From Seeley RR, Stephens TD, Tate P: Anatomy and physiology , ed 7, 5-4 New York, 2006, McGraw-Hill Bones Bones • Scapula, clavicle, & humerus serve as • Key bony landmarks attachments for shoulder joint muscles – Acromion process – Humeral landmarks – Glenoid fossa • Head – Lateral border • Greater tubercle – Inferior angle • Lesser tubercle – Medial border • Intertubercular groove • Deltoid tuberosity – Superior angle – Spine of the scapula © McGraw-Hill Higher Education.