Gravina Access Project Phase I Historic and Archaeological Sites Technical Memorandum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Petition to List the Alexander Archipelago Wolf in Southeast

BEFORE THE SECRETARY OF INTERIOR PETITION TO LIST THE ALEXANDER ARCHIPELAGO WOLF (CANIS LUPUS LIGONI) IN SOUTHEAST ALASKA AS THREATENED OR ENDANGERED UNDER THE U.S. ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT © ROBIN SILVER PETITIONERS CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY, ALASKA RAINFOREST DEFENDERS, AND DEFENDERS OF WILDLIFE JULY 15, 2020 NOTICE OF PETITION David Bernhardt, Secretary U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Margaret Everson, Principal Deputy Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Gary Frazer, Assistant Director for Endangered Species U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1840 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Greg Siekaniec, Alaska Regional Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1011 East Tudor Road Anchorage, AK 99503 [email protected] PETITIONERS Shaye Wolf, Ph.D. Larry Edwards Center for Biological Diversity Alaska Rainforest Defenders 1212 Broadway P.O. Box 6064 Oakland, California 94612 Sitka, Alaska 99835 (415) 385-5746 (907) 772-4403 [email protected] [email protected] Randi Spivak Patrick Lavin, J.D. Public Lands Program Director Defenders of Wildlife Center for Biological Diversity 441 W. 5th Avenue, Suite 302 (310) 779-4894 Anchorage, AK 99501 [email protected] (907) 276-9410 [email protected] _________________________ Date this 15 day of July 2020 2 Pursuant to Section 4(b) of the Endangered Species Act (“ESA”), 16 U.S.C. §1533(b), Section 553(3) of the Administrative Procedures Act, 5 U.S.C. § 553(e), and 50 C.F.R. § 424.14(a), the Center for Biological Diversity, Alaska Rainforest Defenders, and Defenders of Wildlife petition the Secretary of the Interior, through the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (“USFWS”), to list the Alexander Archipelago wolf (Canis lupus ligoni) in Southeast Alaska as a threatened or endangered species. -

Geologic Map of the Ketchikan and Prince Rupert Quadrangles, Southeastern Alaska

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP I-1807 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE KETCHIKAN AND PRINCE RUPERT QUADRANGLES, SOUTHEASTERN ALASKA By Henry C. Berg, Raymond L. Elliott, and Richard D. Koch INTRODUCTION This pamphlet and accompanying map sheet describe the geology of the Ketchikan and Prince Rupert quadrangles in southeastern Alaska (fig. 1). The report is chiefly the result of a reconnaissance investigation of the geology and mineral re sources of the quadrangles by the U.S. Geological Survey dur ing 1975-1977 (Berg, 1982; Berg and others, 1978 a, b), but it also incorporates the results of earlier work and of more re cent reconnaissance and topical geologic studies in the area (fig. 2). We gratefully acknowledge the dedicated pioneering photointerpretive studies by the late William H. (Hank) Con don, who compiled the first 1:250,000-scale reconnaissance geologic map (unpublished) of the Ketchikan quadrangle in the 1950's and who introduced the senior author to the study 130' area in 1956. 57'L__r-'-'~~~;:::::::,~~.::::r----, Classification and nomenclature in this report mainly fol low those of Turner (1981) for metamorphic rocks, Turner and Verhoogen (1960) for plutonic rocks, and Williams and others (1982) for sedimentary rocks and extrusive igneous rocks. Throughout this report we assign metamorphic ages to various rock units and emplacement ages to plutons largely on the basis of potassium-argon (K-Ar) and lead-uranium (Pb-U) (zircon) isotopic studies of rocks in the Ketchikan and Prince Rupert quadrangles (table 1) and in adjacent areas. Most of the isotopic studies were conducted in conjunction with recon naissance geologic and mineral resource investigations and re 0 100 200 KILOMETER sulted in the valuable preliminary data that we cite throughout our report. -

Mammals and Amphibians of Southeast Alaska

8 — Mammals and Amphibians of Southeast Alaska by S. O. MacDonald and Joseph A. Cook Special Publication Number 8 The Museum of Southwestern Biology University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico 2007 Haines, Fort Seward, and the Chilkat River on the Looking up the Taku River into British Columbia, 1929 northern mainland of Southeast Alaska, 1929 (courtesy (courtesy of the Alaska State Library, George A. Parks Collec- of the Alaska State Library, George A. Parks Collection, U.S. tion, U.S. Navy Alaska Aerial Survey Expedition, P240-135). Navy Alaska Aerial Survey Expedition, P240-107). ii Mammals and Amphibians of Southeast Alaska by S.O. MacDonald and Joseph A. Cook. © 2007 The Museum of Southwestern Biology, The University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131-0001. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Special Publication, Number 8 MAMMALS AND AMPHIBIANS OF SOUTHEAST ALASKA By: S.O. MacDonald and Joseph A. Cook. (Special Publication No. 8, The Museum of Southwestern Biology). ISBN 978-0-9794517-2-0 Citation: MacDonald, S.O. and J.A. Cook. 2007. Mammals and amphibians of Southeast Alaska. The Museum of Southwestern Biology, Special Publication 8:1-191. The Haida village at Old Kasaan, Prince of Wales Island Lituya Bay along the northern coast of Southeast Alaska (undated photograph courtesy of the Alaska State Library in 1916 (courtesy of the Alaska State Library Place File Place File Collection, Winter and Pond, Kasaan-04). Collection, T.M. Davis, LituyaBay-05). iii Dedicated to the Memory of Terry Wills (1943-2000) A life-long member of Southeast’s fauna and a compassionate friend to all. -

Chapter 3 Affected Environment

Gravina Access Project Draft Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement Chapter 3 Affected Environment This page intentionally left blank. Gravina Access Project Draft SEIS Affected Environment 3.0 AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT This chapter inventories and characterizes the economic, environmental, and cultural resources in the Gravina Access Project area that could be affected by the proposed project alternatives. This information is drawn from the data, documents, and plans published by a variety of local, state, and governmental agencies, and project-specific technical studies completed by HDR Alaska, Inc., and its affiliates on behalf of DOT&PF, as listed in the References section. All figures referenced in this chapter may be found at the end of the chapter. 3.1 Land Use 3.1.1 Current Land Use This section describes the current land ownership, land uses, and zoning within the project area on Revillagigedo, Pennock, and Gravina islands. General land ownership within the project area is presented below in Table 3.1 and shown in Figure 3.1; land uses are listed in Table 3.2 and shown in Figure 3.2; and project area zoning is summarized in Table 3.3 and shown in Figure 3.3. Native lands in Alaska are typically held by regional and village Native corporations formed by the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act and are considered to be privately owned. Native Village Corporations have been making selections from federal lands over several decades, and some of these selections are still underway in Southeast Alaska. Native Village Corporations have also purchased commercial properties and run businesses in many communities, including Ketchikan. -

Alexander Archipelago Wolf: a Conservation Assessment

United States Department of Agriculture The Alexander Archipelago Forest Service Wolf: A Conservation Pacific Northwest Research Station Assessment General Technical Report PNW-GTR-384 David K. Person, Matthew Kirchhoff, November 1996 Victor Van Ballenberghe, George C. Iverson, and Edward Grossman Authors DAVID K. PERSON is a graduate fellow, Alaska Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK 99775; MATTHEW KIRCHHOFF is a research wildlife biologist, Alaska Department of Fish and Game, P.O. Box 240020 Douglas, AK 99824; VICTOR VAN BALLENBERGHE is a research wildlife biologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, Forestry Sciences Laboratory, 3301 C Street, Suite 200, Anchorage, AK 99503-3954; GEORGE C. IVERSON is the regional ecology program leader, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Alaska Region, P.O. Box 21628, Juneau, AK 99801; and EDWARD GROSSMAN is a wildlife biologist with the U.S. Department of the Interior, Ecological Services, 3000 Vintage Boulevard Suite 205, Juneau, AK 99801. Conservation and Resource Assessments for the Tongass Land Management Plan Revision Charles G. Shaw III Technical Coordinator The Alexander Archipelago Wolf: A Conservation Assessment David K. Person Matthew Kirchhoff Victor Van Ballenberghe George C. Iverson Edward Grossman Published by: U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station Portland, Oregon General Technical Report PNW-GTR-384 November 1996 In cooperation with: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Alaska Department of Fish and Game Abstract Person, David K.; Kirchhoff, Matthew; Van Ballenberghe, Victor; Iverson, George C.; Grossman, Edward. 1996. The Alexander Archipelago wolf: a conservation assessment. -

KETCHIKAN, AK (907) 220-9201 3612 Tongass Avenue Ketchikan, AK 99901 [email protected]

OUR TOWN DISCOVER KETCHIKAN ALASKA’S MOST VIBRANT COMMUNITY Official Publication of HISTORIC KETCHIKAN America’s Newest & Best Extended Stay Hotels NIGHTLY WEEKLY BEST MONTHLY RATES T PE Y L D F R I E N KETCHIKAN, AK (907) 220-9201 3612 Tongass Avenue Ketchikan, AK 99901 [email protected] myplacehotels.com • Toll Free (855)-200-5685 • Each franchise is independently owned and operated. Historic Ketchikan Inc. is pleased to present this book to our visitors, our prospective visitors and our residents as a record of a vibrant and progressive community. POPPEN GREGG OUR TOWN DISCOVER KETCHIKAN ALASKA PUBLISHED BY CO. KETCHIKAN KAYAK WHALE VIDEO: Historic Ketchikan Inc. The town and the Alaskan wilds: WITH SUPPORT FROM We think we have some of the best of both KETCHIKAN GATEWAY BOROUGH AND CITY OF KETCHIKAN here in Ketchikan—and we have the videos to prove it. Historic Ketchikan Inc. Historic Ketchikan Inc. This publication is a community profile with general factual information and residents’ opinions. It is designed to be informative and entertaining— Board of Directors P.O. Box 23364 a tribute to the spirit of a progressive community. It is not intended to be Terry Wanzer PRESIDENT Ketchikan, Alaska 99901 a primary historical reference. Ralph Beardsworth VICE PRESIDENT www.historicketchikan.org © 2018 Historic Ketchikan Inc. All rights reserved. This publication may not Deborah Hayden SECRETARY [email protected] be reproduced in any form except with written permission. Brief passages may be excerpted in reviews. Prior editions of Our Town were published in James Alguire TREASURER 907-225-5515 1994, 1998, 2003, 2008, 2011 and 2015. -

Bookletchart™ Revillagigedo Channel NOAA Chart 17434

BookletChart™ Revillagigedo Channel NOAA Chart 17434 A reduced-scale NOAA nautical chart for small boaters When possible, use the full-size NOAA chart for navigation. Included Area Published by the shelter for small boats. Anchorage is in 2 to 7 fathoms. Local magnetic disturbance.–Extreme magnetic disturbances, with National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration differences of as much as 50° have been observed SE of Duke Island. The National Ocean Service magnetic compass should not be relied upon within the area outlined in Office of Coast Survey magenta on the charts. East Island, marked by a light on its E side, is a small island, 2.5 miles S www.NauticalCharts.NOAA.gov of Duke Point, the easternmost point of Duke Island. Round East Island 888-990-NOAA with great care because of the outlying rocks to the W, the magnetic disturbance, and the uncertainty of the tidal currents. What are Nautical Charts? Hassler Reef is an extensive shoal area with depths of 3¼ to 10 fathoms about 7.8 miles W of Mount Lazaro. The reef is covered by heavy kelp Nautical charts are a fundamental tool of marine navigation. They show during the summer and has deep water close-to. Very irregular bottom water depths, obstructions, buoys, other aids to navigation, and much extends 3 miles to the S of Hassler Reef, and passage over that section is more. The information is shown in a way that promotes safe and not recommended. efficient navigation. Chart carriage is mandatory on the commercial A rocky shoal, covered 3 fathoms with breakers in its immediate vicinity, ships that carry America’s commerce. -

2021-2022 Alaska Hunting Regulations

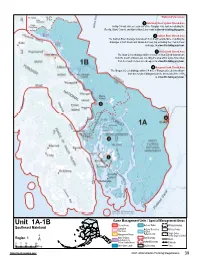

State restricted areas: 1 Ketchikan Road System Closed Area A strip 1/4 mile wide on each side of the Tongass Hwy system including the Revilla, Ward, Connel, and Harriet Hunt Lake roads is closed to taking big game. 2 Salmon River Closed Area The Salmon River drainage downstream from the Riverside Mine, including the drainages of Fish Creek and Skookum Creek, but excluding the Thumb Creek drainage, is closed to taking any bear. 3 Anan Creek Closed Area The Anan Creek drainage within one mile of Anan Creek downstream from the mouth of Anan Lake including the area within a one-mile radius from the mouth of Anan Creek Lagoon is closed to taking any bear. 4 Margaret Creek Closed Area The Margaret Creek drainage within 1/4 mile of Margaret Creek downstream from the mouth of Margaret Lake to the mouth of the creek is closed to taking any bear. 26 Game Management Units / Special Management Areas 23 Unit 1A-1B 24 25 Closed Areas National Parks Military Boundary Southeast Mainland 22 20 Controlled 21 National Preserves Military Closure 12 Use Areas & Other 13 18 19 16 14 Tangle Lakes 11 Federal Lands 6 Management Areas 5 Archaeological District 15 7 1 17 State Refuges, Unit Boundary Region 1 4 ± 9 3 Roads 1 Sanctuaries, & 8 2 Subunit Boundary 0 5 10 20 Critical Habitat Areas Railroads Miles 10 Other State Lands City Boundary Trails U:\WC\regbook_MPS\MXD_2013\P.mxd 4/3/2013 skt http://hunt.alaska.gov 2021-2022 Alaska Hunting Regulations 39 State Restricted Areas: 1 Juneau Road System Closed Area: The area between the coast and a line 1/4 mile inland of the following road systems: Glacier Hwy from mile 0 to the northern bank at Peterson Creek, Douglas Hwy from the Douglas city limits to the northeast bank of Fish Creek, Mendenhall Loop Road and Thane Road; is closed to taking big game. -

2018-06 Ketchikan Consolidation Application

PETITION FOR CONSOLIDATION OF THE KETCHIKAN GATEWAY BOROUGH AND THE CITY OF KETCHIKAN TO THE MUNICIPALITY OF KETCHIKAN, A HOME RULE BOROUGH1 To: The State Of Alaska, Local Boundary Commission: The Petitioner hereby requests that the Local Boundary Commission grant this petition for consolidation resulting in the dissolution of the home rule city and general law borough described herein and the incorporation of a home rule borough under the provisions of Article X, Sections 1, 3, and 5 of Alaska’s constitution; AS 29.06.090 - AS 29.06.170; 3 AAC 110.240 - 3 AAC 110.250; 3 AAC 110.400 - 3 AAC 110.660; and 3 AAC 110.900 - 3 AAC 110.990. 1. CONSOLIDATION PROPOSAL. The Petitioner, the City of Ketchikan, a political subdivision of the State of Alaska, hereby petitions to dissolve the municipalities named below and to incorporate, through consolidation, the home rule borough named below and described in this petition: Municipalities to be Dissolved by Consolidation: Name: City of Ketchikan (hereafter “City”). Class: home rule. Name: Ketchikan Gateway Borough (hereafter “Borough”). Class: second class borough. Home Rule Borough to be Incorporated by Consolidation: Name: Municipality of Ketchikan (hereafter “Municipality”). Class: home rule. 2. POPULATION. The populations of the municipalities proposed for consolidation are estimated to be as follows: City of Ketchikan: 8,3202 Ketchikan Gateway Borough (including City) 13,9613 3. REASONS FOR CONSOLIDATION. A summary of the principal reasons for the consolidation proposal is provided as Exhibit A. 1This petition, including the Charter, transition plan, proposed taxes and budget are subject to amendment by the Petitioner in accordance with 3 AAC 110.540 or, after submittal, by the Local Boundary Commission. -

Gravina Access Project

Gravina Access Project Construction Impacts Technical Memorandum Draft Agreement 36893013 DOT&PF Project 67698 Federal Project ACHP-0922 (5) Prepared for: State of Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities 6860 Glacier Highway Juneau, Alaska 99801 Prepared by: HDR Alaska, Inc. 712 West 12th Street Juneau, AK 99801 December 2001 Construction Impacts Executive Summary The purpose of this Memorandum is to discuss the potential temporary impacts of constructing additional access to Gravina Island. The Memorandum considers the specific impacts of bridge and bridge-approach construction for Alternatives C3(a), C3(b), C4, D1, and F3; ferry terminal construction for Alternatives G2, G3, and G4; and roadway construction for all alternatives. Long-term impacts, such as the impact of bridge construction and subsequent closure or restriction of operations in the East and West Channels on the tourism economy, effects of piers and other in-water structures, and impacts to aviation, including floatplanes, are not considered. The evaluation is divided into 11 areas of potential impact: land use, social and economic environment, physical environment, biological resources, historic and archaeological resources, visual environment, transportation, hazardous waste sites, utilities, and energy. All of the alternatives will require the use of staging areas for equipment and materials. Impacts to these areas are expected to be temporary. The land will be returned to its previous use when construction is finished and revegetated with native plants and soils as needed. In addition, land for right-of-way and for roadways, bridges, and terminals will need to be acquired. Any habitat or wetlands on this land will be lost, though the alternative alignments were selected to avoid impacts to wetlands and streams to the extent practicable. -

TONGASS NATIONAL FOREST 2020 VISITOR GUIDE TABLE of CONTENTS GETTING the MOST out Welcome to the of YOUR VISIT

TONGASS NATIONAL FOREST 2020 VISITOR GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS GETTING THE MOST OUT Welcome to the OF YOUR VISIT...............................3 TONGASS FISHERIES....................4 SALMON FACTS............................5 Tongass National CABINS & CAMPGROUNDS......... 5 KIDS, FISHING AND A CHILDREN’S FOREST.................6 Forest! FOREST MAP...............................8-9 At nearly 17 million acres, this is the largest National TONGASS FACTS...........................9 ANNUAL RAINFALL.......................9 Forest in the Unites States, and the largest contiguous BEAR VIEWING............................10 temperate rainforest in the world. The Tongass BEAR ENCOUNTERS....................11 National Forest is a public treasure. It is a land of SAWMILL CREEK beauty, mystery, and untold natural riches. Since time CAMPGROUND...........................12 immemorial, this forest has nourished and sustained SUSTAINABLE rich and unique human cultures. RECREATION .........................13-14 LEARN MORE...............................15 It continues to sustain Alaskan communities and CONTACT US................ Back Cover culture today by creating jobs and bringing revenue through tourism, recreation, watersheds, fisheries and timber. The Tongass NF sees more than 2.8 million visitors annually, generating more than $380 million in spending and over 5,000 jobs!* All of this while protecting and maintaining some of the most diverse and beautiful ecosystems in the country. The Tongass has something for everyone. Explore, renew, and refresh among the islands and along the coastline here in the Tongass, and take home exciting memories of adventures in Alaska. We hope you enjoy your time in the Last Frontier and will choose to return often. M. Earl Stewart FOREST SUPERVISOR, TONGASS NATIONAL FOREST 2 PETERSBURG, MITKOF ISLAND Getting the Most The Petersburg Ranger District maintains several scenic recreation sites, including a newly refurbished, accessible picnic/day-use area and Swan Observatory. -

UAS Campus Master Plan 2012

TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY . 1 4.0 FUTURE CAMPUS . .67 Figure 1.1 Juneau Auke Lake Campus Core . .1.4 Figure 2.26 Ketchikan Upper Campus Building Condition . 2.26 Introduction . 1 Introduction . 67 Figure 1.1 Juneau Technology Education Center . .1.4 Figure 2.27 Ketchikan Lower Campus Building Condition . 2.26 UAS Mission & Core Themes . 1 Campus Based Academic Specialties . 68 Figure 1.1 Ketchikan Upper Campus . .1.5 Figure 2.28 Ketchikan Upper Campus Green Space . 2.27 Looking Forward: The UAS Campus Master Plan 2012 . 2 Alignment of Campus Master Plan with UAS Core Themes . 70 Figure 1.1 Ketchikan Lower Campus . .1.5 Figure 2.29 Ketchikan Lower Campus Green Space . 2.27 Compliance with UA Board of Regents’ Master Planning Policy 3 Campus Kwáan . 72 Figure 1.1 Sitka Campus . .1.5 Figure 2.30 Ketchikan Upper Campus . Circulation and Parking . 2.28 Alignment Of Campus Master Plan With UAS Core Themes . 4 Juneau . 74 Figure 2.1 Juneau Large Scale Context . .2.2 Figure 2.31 Ketchikan Lower Campus . 2.0 EXISTING CAMPUS CONDITIONS . 7 Technology Education Center . 80 Figure 2.3 Juneau Auke Lake Land Use Diagram . .2.4 Circulation and Parking . 2.28 Introduction . 7 Sitka . 82 Figure 2.2 Juneau Downtown Land Use Diagram . .2.4 Juneau . 8 Ketchikan . 85 Figure 2.4 Juneau Auke Lake Property Aquisition Plan . .2.5 Technical Education Center . 22 5.0 IMPLEMENTATION . .89 Figure 2.5 Juneau Auke Lake Building Use . .2.7 Bill Ray Center . 24 Introduction .