Chapter 3 Affected Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Alaska Boundary Dispute

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2014 A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939 Smith, Gordon W. University of Calgary Press "A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939", Gordon W. Smith; edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2014 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/50251 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca A HISTORICAL AND LEGAL STUDY OF SOVEREIGNTY IN THE CANADIAN NORTH: TERRESTRIAL SOVEREIGNTY, 1870–1939 By Gordon W. Smith, Edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer ISBN 978-1-55238-774-0 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at ucpress@ ucalgary.ca Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specificwork without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

Capital Project Summary Department of Transportation and Public Facilities FY2007 Governor Amended Reference No: 41919 4/28/06 2:59:44 PM Page: 1

Gravina Island Bridge FY2007 Request: $91,000,000 Reference No: 41919 AP/AL: Allocation Project Type: Construction Category: Transportation Location: Ketchikan Contact: John MacKinnon House District: Ketchikan Contact Phone: (907)465-6973 Estimated Project Dates: 07/01/2006 - 06/03/2011 Appropriation: Congressional Earmarks Brief Summary and Statement of Need: Improve surface access between Ketchikan and Gravina Island, including the Ketchikan International Airport. This project contributes to the Department's Mission by reducing injuries, fatalities and property damage, by improving the mobility of people and goods and by increasing private investment. Funding: FY2007 FY2008 FY2009 FY2010 FY2011 FY2012 Total Fed Rcpts $91,000,000 $91,000,000 Total: $91,000,000 $0 $0 $0 $0 $0 $91,000,000 State Match Required One-Time Project Phased - new Phased - underway On-Going 9% = Minimum State Match % Required Amendment Mental Health Bill Operating & Maintenance Costs: Amount Staff Project Development: 0 0 Ongoing Operating: 0 0 One-Time Startup: 0 Totals: 0 0 Additional Information / Prior Funding History: FY2005 - $215,000,000; FY2002 - $20,000,000; FY1999 - $20,200,000. Project Description/Justification: The Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities (DOT&PF), in cooperation with the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), proposes to start the final step toward constructing access from Revillagigedo (Revilla) Island to Gravina Island in Southeast Alaska. It is intended to provide a roadway link from Ketchikan to Gravina Island across the Ralph M. Bartholomew Veterans' Memorial Bridges over two channels of Tongass Narrows. Pennock Island in the Narrows is also now accessible. The proposed Gravina Island Highway begins as the Airport Access Road at the Ketchikan International Airport parking lot on Gravina Island and extends south around the end of the present day runway and up the hill to an intersection with Gravina Island Highway and Lewis Reef Road. -

Southeast Alaska Sea Cucumber Commercial Fishery Area Rotation

Alaska Department of Fish and Gam e Southeast Alaska Sea Cucumber Open Season Commercial Fishery Area Rotation (October 1 - March 31) Map IV.b. (southern Southeast) ! 2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 South Mitkof and North Zarembo Islands Wrangell Zimovia Strait and Anita Bay ! Stikine Strait and Chichagof Passage Bradfield Canal, Blake Channel and Eastern Passage µ Snow Pass Northern Ernest Sound North Behm Canal Clarence Strait West Behm Canal 101-85 Rudyerd Bay, Southern Ernest Sound East Behm Canal, Thorne Bay and Kasaan Peninsula and Walker Cove George Inlet, SanSan ChristovalChristoval West Behm Canal Cleveland Peninsula Bold Island, Channel,Channel, westernwestern 101-90, 95 San Alberto Bay, and Carroll Inlet San Alberto Bay, Kasaan Bay andand TrocaderoTrocadero BayBay and Skowl Arm Tongass Craig Narrows East Behm Canal ! and Smeaton Bay Clarence Strait ! Ketchikan Revillagigedo Channel, Cholmondeley Thorne Arm, and Sound East Behm Canal West Shore of Bucareli Bay and Gravina Island Port Real Marina Moira Sound Eastern shore Boca de of Dall Island Quadra and Soda Bay Lower Hetta Inlet, Clarence Percy Islands Nutkwa Inlet, Strait and Keete Inlet Long Island and upper Cordova Bay Clarence Strait and Dixon Entrance Tree Point Willard and Revillagigedo Channel Fillmore Inlets and Southern Clarence Strait Revillagigedo Channel and Felice Strait 25 12.5 0 25 50 Nautical Miles Last modified: 10/24/2018 Map Datum and Projection: NAD 83 Alaska 1 State Plane FIPS 5001 (meters) Mike Donnellan. -

Bulletin of the United States Fish Commission

SALMON-TAGGING EXPERIMENTS IN ALASKA, 1924 AND 1925 1 .:I- By WILLIS H. RICH, Ph. D. Director, U. S. Biological Station, Seattle, Wash; .:I CONTENTS Page Introduction _ 109 Experiments in southeastern Alaska__hhu u __nn_h__u u u _ 116 Tagging record _ 116 Returns from experiments in Icy Strait__ n h_u u_..u u _ 119 Returns from experiments in Frederick Sound u huh _ 123 Returns from experiments in Chatham Strait; h u • _ 123 Returns from experiments in Sumner Strait, u_uuu .. u _ 128 Returns from experiments at Cape Muzon and Kaigani Point, ~ _ 135 Returns from experiments at Cape Chacon u n u h _ 137 Returns from experiments near Cape Fox and Duke Islandu _ 141 Variations in returns of tagged fish; h _u u n n h n __ h u_ 143 Conelusions _ 144 Experiments at Port Moller, 1925un__h_uu uu __ 145 INTRODUCTION The extensive salmon-tagging experiments conducted during 1922 and 1923 2 in the region of the Alaska Peninsula proved so productive of information, both of scientific interest and of practical application in the care of these fisheries, that it was considered desirable to undertake similar investigations in other districts; Accordingly, experiments were carried on in southeastern Alaska in 1924 and again in 1925. In 1925, also, at the request of one of the companies engaged in packing salmon in the Port Moller district, along the northern shore of the Alaska Penin sula, the work done there in 1922 was repeated. The results of these experiments form the basis for the following report. -

Southern Southeast Inside Commercial Sablefish Fishery and Survey Activities in Southeast Alaska, 2013

Fishery Management Report No. 14-39 Southern Southeast Inside Commercial Sablefish Fishery and Survey Activities in Southeast Alaska, 2013 by Jennifer Stahl, Kamala Carroll, and Kristen Green October 2014 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Divisions of Sport Fish and Commercial Fisheries Symbols and Abbreviations The following symbols and abbreviations, and others approved for the Système International d'Unités (SI), are used without definition in the following reports by the Divisions of Sport Fish and of Commercial Fisheries: Fishery Manuscripts, Fishery Data Series Reports, Fishery Management Reports, and Special Publications. All others, including deviations from definitions listed below, are noted in the text at first mention, as well as in the titles or footnotes of tables, and in figure or figure captions. Weights and measures (metric) General Mathematics, statistics centimeter cm Alaska Administrative all standard mathematical deciliter dL Code AAC signs, symbols and gram g all commonly accepted abbreviations hectare ha abbreviations e.g., Mr., Mrs., alternate hypothesis HA kilogram kg AM, PM, etc. base of natural logarithm e kilometer km all commonly accepted catch per unit effort CPUE liter L professional titles e.g., Dr., Ph.D., coefficient of variation CV meter m R.N., etc. common test statistics (F, t, χ2, etc.) milliliter mL at @ confidence interval CI millimeter mm compass directions: correlation coefficient east E (multiple) R Weights and measures (English) north N correlation coefficient cubic feet per second ft3/s south S (simple) r foot ft west W covariance cov gallon gal copyright degree (angular ) ° inch in corporate suffixes: degrees of freedom df mile mi Company Co. -

Journal of Marine Research, Sears Foundation for Marine Research

The Journal of Marine Research is an online peer-reviewed journal that publishes original research on a broad array of topics in physical, biological, and chemical oceanography. In publication since 1937, it is one of the oldest journals in American marine science and occupies a unique niche within the ocean sciences, with a rich tradition and distinguished history as part of the Sears Foundation for Marine Research at Yale University. Past and current issues are available at journalofmarineresearch.org. Yale University provides access to these materials for educational and research purposes only. Copyright or other proprietary rights to content contained in this document may be held by individuals or entities other than, or in addition to, Yale University. You are solely responsible for determining the ownership of the copyright, and for obtaining permission for your intended use. Yale University makes no warranty that your distribution, reproduction, or other use of these materials will not infringe the rights of third parties. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. Journal of Marine Research, Sears Foundation for Marine Research, Yale University PO Box 208118, New Haven, CT 06520-8118 USA (203) 432-3154 fax (203) 432-5872 [email protected] www.journalofmarineresearch.org RELATION OF POPULATION SIZE TO MARINE GROWTH AND TIME OF SPAWNING MIGRATION IN THE PINK SALMON ( Oncorhynchus gorbuscha) OF SOUTHEASTERN ALASKA F. -

Southern Southeast Alaska Pink Salmon Tagging Investigations, 1981. Southeast Alaska Stock Separation Research Project, Annual R

SOUTHERN SOUTHEAST ALASKA PINK SALMON INVESTIGATIONS, 1981. Southeast Alaska Stock Separation Research Project Annual Report – 1982 By Steve H. Hoffman Regional Information Report1 1J92-20 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Commercial Fisheries Juneau, Alaska December 1992 1 The Regional Information Report Series was established in 1987 to provide an information access system for all unpublished divisional reports. These reports frequently serve diverse ad hoc informational purposes or archive basic uninterpreted data. To accommodate timely reporting of recently collected information, reports in this series undergo only limited internal review and may contain preliminary data; this information may be subsequently finalized and published in the formal literature. Consequently, these reports should not be cited without prior approval of the author or the Division of Commercial Fisheries. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ............................. LISTOFFIGURES ........................... LISTOFAPPENDICES ......................... ABSTRACT .............................. INTRODUCTION ............................ OBJECTIVES ............................. PREVIOUS TAGGING STUDIES ...................... METHODS ............................... TagsEmployed ........................ Tagging Operations ...................... TagRecovery ......................... DataAnalysis ......................... RESULTS ............................... Tagging ............................ Spawning Ground Tag Recovery ................. Commercial -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 112 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 112 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 157 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, MARCH 2, 2011 No. 30 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was For some reason, their moral sen- ican lives. Our surviving servicemen called to order by the Speaker pro tem- sibilities are not offended by a military and -women are coming home with dev- pore (Mr. YODER). conflict that has cost us hundreds of astating physical and psychological f billions of dollars and 1,500 of our brav- wounds. Yet the majority party, so en- est, bravest people without advancing thusiastic in its support for Afghani- DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO national security objectives or truly stan spending, wants to eliminate a TEMPORE diminishing the terrorist threat at the homeless veterans initiative. The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- same time. That’s their version of morality: fore the House the following commu- So how are my colleagues on the Send young Americans halfway around nication from the Speaker: other side of the aisle resolving their the world to be chewed up and trauma- WASHINGTON, DC, moral dilemma? By asking corporate tized. Then pull the plug on the sup- March 2, 2011. special interests to give up handouts port they need when they get home. I hereby appoint the Honorable KEVIN and tax breaks? By asking the wealthi- That’s what they call supporting the YODER to act as Speaker pro tempore on this est Americans to give back more to the troops. -

Gravina Freight Dock Facility Geotechnical Data Report

April 2020 Prepared by: P N D ENGINEERS, INC. G r a v i n a F r e i g h t D o c k F a c i l i t y G e o t e c h n i c a l I n ve s t i ga t i o n Geo t ec h n i ca l Da t a Re p or t F i n a l Re p or t Prepared for: April 2020 Gravina Freight Dock Facility Geotechnical Data Report TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Figures .................................................................................................................................................................. ii List of Tables ....................................................................................................................................................................... ii Appendices .......................................................................................................................................................................... iii 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................... 1 2. PROJECT BACKGROUND AND DESCRIPTION ....................................................................................... 1 2.1 Description ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 2.2 Site Geography .................................................................................................................................................. 2 2.3 Existing Site Conditions ................................................................................................................................. -

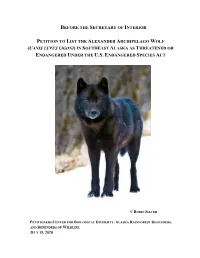

Petition to List the Alexander Archipelago Wolf in Southeast

BEFORE THE SECRETARY OF INTERIOR PETITION TO LIST THE ALEXANDER ARCHIPELAGO WOLF (CANIS LUPUS LIGONI) IN SOUTHEAST ALASKA AS THREATENED OR ENDANGERED UNDER THE U.S. ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT © ROBIN SILVER PETITIONERS CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY, ALASKA RAINFOREST DEFENDERS, AND DEFENDERS OF WILDLIFE JULY 15, 2020 NOTICE OF PETITION David Bernhardt, Secretary U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Margaret Everson, Principal Deputy Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Gary Frazer, Assistant Director for Endangered Species U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1840 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Greg Siekaniec, Alaska Regional Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1011 East Tudor Road Anchorage, AK 99503 [email protected] PETITIONERS Shaye Wolf, Ph.D. Larry Edwards Center for Biological Diversity Alaska Rainforest Defenders 1212 Broadway P.O. Box 6064 Oakland, California 94612 Sitka, Alaska 99835 (415) 385-5746 (907) 772-4403 [email protected] [email protected] Randi Spivak Patrick Lavin, J.D. Public Lands Program Director Defenders of Wildlife Center for Biological Diversity 441 W. 5th Avenue, Suite 302 (310) 779-4894 Anchorage, AK 99501 [email protected] (907) 276-9410 [email protected] _________________________ Date this 15 day of July 2020 2 Pursuant to Section 4(b) of the Endangered Species Act (“ESA”), 16 U.S.C. §1533(b), Section 553(3) of the Administrative Procedures Act, 5 U.S.C. § 553(e), and 50 C.F.R. § 424.14(a), the Center for Biological Diversity, Alaska Rainforest Defenders, and Defenders of Wildlife petition the Secretary of the Interior, through the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (“USFWS”), to list the Alexander Archipelago wolf (Canis lupus ligoni) in Southeast Alaska as a threatened or endangered species. -

The Building Blocks of Government”, Chapter 7 from the Book a Primer on Politics (Index.Html) (V

This is “The Building Blocks of Government”, chapter 7 from the book A Primer on Politics (index.html) (v. 0.0). This book is licensed under a Creative Commons by-nc-sa 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/ 3.0/) license. See the license for more details, but that basically means you can share this book as long as you credit the author (but see below), don't make money from it, and do make it available to everyone else under the same terms. This content was accessible as of December 29, 2012, and it was downloaded then by Andy Schmitz (http://lardbucket.org) in an effort to preserve the availability of this book. Normally, the author and publisher would be credited here. However, the publisher has asked for the customary Creative Commons attribution to the original publisher, authors, title, and book URI to be removed. Additionally, per the publisher's request, their name has been removed in some passages. More information is available on this project's attribution page (http://2012books.lardbucket.org/attribution.html?utm_source=header). For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page (http://2012books.lardbucket.org/). You can browse or download additional books there. i Chapter 7 The Building Blocks of Government PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final. We may sometimes think of government as a monolithic force, acting in concert to achieve its ends like a well-trained team. In fact, government is a lot of people divided into a lot of different parts. -

Ketchikan and Prince Rupert Quadrangles, Southeastern Alaska

The Alaska Mineral Resource Assessment Program: Guide to Information about the Geology and Mineral Resources of the Ketchikan and Prince Rupert Quadrangles, Southeastern Alaska By Henry C. Berg GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 855 United States Department of the Interior JAMES G. WATT, Secretary Geological Survey Dallas L. Peck, Director Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Berg, Henry Clayr 1929- The Alaska Mineral;peswrcer Assessment Program: Guide to information about the geoiogy and mineral resources of the Ketchikan h&.~fince'l?upert quadrangles, southeastern Alaska. 3 (Geological Survey circular ; 8551 Bibliography: p. 21-24 Supt. of Docs. no.: I19.4/2:855 1. Mines and mineral resources--Alaska. 2. Geology-- Alaska. I. Title. 11. Series: United States. Geological Survey. Circular 855. QE75.CS no. 855 622 s 82-600083 CTN24. A41 t557.98'21 AACR2 Free on application to Branch of Distribution, U.S. Geological Sumey 604 South Pickett Street, Alexandria, VA 22304 CONTENTS Page Abstract ............................................................................................ 1 Descriptionsof component mapsand reportsofthe Ketchikan Introduction ...................................................................................... 1 and Prince Rupert quadrangles AMRAP folio Purpose and scope .................................................................. 1 and of subsequent related investigations-Continued Geography and access ............................................................ 1 Tectonostratigraphic terranes and structural