Sculptures in Granite

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southeast Alaska Sea Cucumber Commercial Fishery Area Rotation

Alaska Department of Fish and Gam e Southeast Alaska Sea Cucumber Open Season Commercial Fishery Area Rotation (October 1 - March 31) Map IV.b. (southern Southeast) ! 2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 South Mitkof and North Zarembo Islands Wrangell Zimovia Strait and Anita Bay ! Stikine Strait and Chichagof Passage Bradfield Canal, Blake Channel and Eastern Passage µ Snow Pass Northern Ernest Sound North Behm Canal Clarence Strait West Behm Canal 101-85 Rudyerd Bay, Southern Ernest Sound East Behm Canal, Thorne Bay and Kasaan Peninsula and Walker Cove George Inlet, SanSan ChristovalChristoval West Behm Canal Cleveland Peninsula Bold Island, Channel,Channel, westernwestern 101-90, 95 San Alberto Bay, and Carroll Inlet San Alberto Bay, Kasaan Bay andand TrocaderoTrocadero BayBay and Skowl Arm Tongass Craig Narrows East Behm Canal ! and Smeaton Bay Clarence Strait ! Ketchikan Revillagigedo Channel, Cholmondeley Thorne Arm, and Sound East Behm Canal West Shore of Bucareli Bay and Gravina Island Port Real Marina Moira Sound Eastern shore Boca de of Dall Island Quadra and Soda Bay Lower Hetta Inlet, Clarence Percy Islands Nutkwa Inlet, Strait and Keete Inlet Long Island and upper Cordova Bay Clarence Strait and Dixon Entrance Tree Point Willard and Revillagigedo Channel Fillmore Inlets and Southern Clarence Strait Revillagigedo Channel and Felice Strait 25 12.5 0 25 50 Nautical Miles Last modified: 10/24/2018 Map Datum and Projection: NAD 83 Alaska 1 State Plane FIPS 5001 (meters) Mike Donnellan. -

Holocene Tephras in Lake Cores from Northern British Columbia, Canada

935 Holocene tephras in lake cores from northern British Columbia, Canada Thomas R. Lakeman, John J. Clague, Brian Menounos, Gerald D. Osborn, Britta J.L. Jensen, and Duane G. Froese Abstract: Sediment cores recovered from alpine and subalpine lakes up to 250 km apart in northern British Columbia con- tain five previously unrecognized tephras. Two black phonolitic tephras, each 5–10 mm thick, occur within 2–4 cm of each other in basal sediments from seven lakes in the Finlay River – Dease Lake area. The upper and lower Finlay tephras are slightly older than 10 220 – 10 560 cal year B.P. and likely originate from two closely spaced eruptions of one or two large volcanoes in the northern Cordilleran volcanic province. The Finlay tephras occur at the transition between deglacial sediments and organic-rich postglacial mud in the lake cores and, therefore, closely delimit the termination of the Fraser Glaciation in northern British Columbia. Sediments in Bob Quinn Lake, which lies on the east edge of the northern Coast Mountains, contain two black tephras that differ in age and composition from the Finlay tephras. The lower Bob Quinn tephra is 3–4 mm thick, basaltic in composition, and is derived from an eruption in the Iskut River volcanic field about 9400 cal years ago. The upper Bob Quinn tephra is 12 mm thick, trachytic in composition, and probably 7000–8000 cal years old. A fifth tephra occurs as a cryptotephra near the top of two cores from the Finlay River area and is correlated to the east lobe of the White River tephra (ca. -

Journal of Marine Research, Sears Foundation for Marine Research

The Journal of Marine Research is an online peer-reviewed journal that publishes original research on a broad array of topics in physical, biological, and chemical oceanography. In publication since 1937, it is one of the oldest journals in American marine science and occupies a unique niche within the ocean sciences, with a rich tradition and distinguished history as part of the Sears Foundation for Marine Research at Yale University. Past and current issues are available at journalofmarineresearch.org. Yale University provides access to these materials for educational and research purposes only. Copyright or other proprietary rights to content contained in this document may be held by individuals or entities other than, or in addition to, Yale University. You are solely responsible for determining the ownership of the copyright, and for obtaining permission for your intended use. Yale University makes no warranty that your distribution, reproduction, or other use of these materials will not infringe the rights of third parties. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. Journal of Marine Research, Sears Foundation for Marine Research, Yale University PO Box 208118, New Haven, CT 06520-8118 USA (203) 432-3154 fax (203) 432-5872 [email protected] www.journalofmarineresearch.org RELATION OF POPULATION SIZE TO MARINE GROWTH AND TIME OF SPAWNING MIGRATION IN THE PINK SALMON ( Oncorhynchus gorbuscha) OF SOUTHEASTERN ALASKA F. -

Geographic Names

GEOGRAPHIC NAMES CORRECT ORTHOGRAPHY OF GEOGRAPHIC NAMES ? REVISED TO JANUARY, 1911 WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1911 PREPARED FOR USE IN THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE BY THE UNITED STATES GEOGRAPHIC BOARD WASHINGTON, D. C, JANUARY, 1911 ) CORRECT ORTHOGRAPHY OF GEOGRAPHIC NAMES. The following list of geographic names includes all decisions on spelling rendered by the United States Geographic Board to and including December 7, 1910. Adopted forms are shown by bold-face type, rejected forms by italic, and revisions of previous decisions by an asterisk (*). Aalplaus ; see Alplaus. Acoma; township, McLeod County, Minn. Abagadasset; point, Kennebec River, Saga- (Not Aconia.) dahoc County, Me. (Not Abagadusset. AQores ; see Azores. Abatan; river, southwest part of Bohol, Acquasco; see Aquaseo. discharging into Maribojoc Bay. (Not Acquia; see Aquia. Abalan nor Abalon.) Acworth; railroad station and town, Cobb Aberjona; river, IVIiddlesex County, Mass. County, Ga. (Not Ackworth.) (Not Abbajona.) Adam; island, Chesapeake Bay, Dorchester Abino; point, in Canada, near east end of County, Md. (Not Adam's nor Adams.) Lake Erie. (Not Abineau nor Albino.) Adams; creek, Chatham County, Ga. (Not Aboite; railroad station, Allen County, Adams's.) Ind. (Not Aboit.) Adams; township. Warren County, Ind. AJjoo-shehr ; see Bushire. (Not J. Q. Adams.) Abookeer; AhouJcir; see Abukir. Adam's Creek; see Cunningham. Ahou Hamad; see Abu Hamed. Adams Fall; ledge in New Haven Harbor, Fall.) Abram ; creek in Grant and Mineral Coun- Conn. (Not Adam's ties, W. Va. (Not Abraham.) Adel; see Somali. Abram; see Shimmo. Adelina; town, Calvert County, Md. (Not Abruad ; see Riad. Adalina.) Absaroka; range of mountains in and near Aderhold; ferry over Chattahoochee River, Yellowstone National Park. -

Pleistocene Volcanism in the Anahim Volcanic Belt, West-Central British Columbia

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2014-10-24 A Second North American Hot-spot: Pleistocene Volcanism in the Anahim Volcanic Belt, west-central British Columbia Kuehn, Christian Kuehn, C. (2014). A Second North American Hot-spot: Pleistocene Volcanism in the Anahim Volcanic Belt, west-central British Columbia (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/25002 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/1936 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY A Second North American Hot-spot: Pleistocene Volcanism in the Anahim Volcanic Belt, west-central British Columbia by Christian Kuehn A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN GEOLOGY AND GEOPHYSICS CALGARY, ALBERTA OCTOBER, 2014 © Christian Kuehn 2014 Abstract Alkaline and peralkaline magmatism occurred along the Anahim Volcanic Belt (AVB), a 330 km long linear feature in west-central British Columbia. The belt includes three felsic shield volcanoes, the Rainbow, Ilgachuz and Itcha ranges as its most notable features, as well as regionally extensive cone fields, lava flows, dyke swarms and a pluton. Volcanic activity took place periodically from the Late Miocene to the Holocene. -

Alaska Region New Employee Orientation Front Cover Shows Employees Working in Various Ways Around the Region

Forest Service UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Alaska Region | September 2021 Alaska Region New Employee Orientation Front cover shows employees working in various ways around the region. Alaska Region New Employee Orientation R10-UN-017 September 2021 Juneau’s typically temperate, wet weather is influenced by the Japanese Current and results in about 300 days a year with rain or moisture. Average rainfall is 92 inches in the downtown area and 54 inches ten miles away at the airport. Summer temperatures range between 45 °F and 65 °F (7 °C and 18 °C), and in the winter between 25 °F and 35 °F (-4 °C and -2 °C). On average, the driest months of the year are April and May and the wettest is October, with the warmest being July and the coldest January and February. Table of Contents National Forest System Overview ............................................i Regional Office .................................................................. 26 Regional Forester’s Welcome ..................................................1 Regional Leadership Team ........................................... 26 Alaska Region Organization ....................................................2 Acquisitions Management ............................................ 26 Regional Leadership Team (RLT) ............................................3 Civil Rights ................................................................... 26 Common Place Names .............................................................4 Ecosystems Planning and Budget ................................ -

Ketchikan and Prince Rupert Quadrangles, Southeastern Alaska

The Alaska Mineral Resource Assessment Program: Guide to Information about the Geology and Mineral Resources of the Ketchikan and Prince Rupert Quadrangles, Southeastern Alaska By Henry C. Berg GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 855 United States Department of the Interior JAMES G. WATT, Secretary Geological Survey Dallas L. Peck, Director Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Berg, Henry Clayr 1929- The Alaska Mineral;peswrcer Assessment Program: Guide to information about the geoiogy and mineral resources of the Ketchikan h&.~fince'l?upert quadrangles, southeastern Alaska. 3 (Geological Survey circular ; 8551 Bibliography: p. 21-24 Supt. of Docs. no.: I19.4/2:855 1. Mines and mineral resources--Alaska. 2. Geology-- Alaska. I. Title. 11. Series: United States. Geological Survey. Circular 855. QE75.CS no. 855 622 s 82-600083 CTN24. A41 t557.98'21 AACR2 Free on application to Branch of Distribution, U.S. Geological Sumey 604 South Pickett Street, Alexandria, VA 22304 CONTENTS Page Abstract ............................................................................................ 1 Descriptionsof component mapsand reportsofthe Ketchikan Introduction ...................................................................................... 1 and Prince Rupert quadrangles AMRAP folio Purpose and scope .................................................................. 1 and of subsequent related investigations-Continued Geography and access ............................................................ 1 Tectonostratigraphic terranes and structural -

Ketchikan, Alaska, US

Ketchikan, Alaska, US - Tuesday, August 20, 2019: Built out over the water and climbing weathered stairways, Ketchikan clings to the shores of Tongass Narrows and drapes the mountains with a cheerful air. Besides the main attractions - Creek Street, the Tongass Historical Museum, Totem Bight State Park and Saxman Village, try a flightseeing trip to breathtaking Misty Fjords National Monument--a transformational adventure not to be missed. These deep water fjords left by retreating glaciers left granite cliffs towering thousands of feet above the sea and countless waterfalls cascading into placid waters. The souvenir photos you'll take from the pontoons of the plane are worth the trip alone. Adventure Kart Expedition Forest, Behm Canal and Alaska's fabled Inside flight by floatplane, headed to a remote site in personal item per passenger. Ample storage is Passage. the Tongass National Forest noted for its available to guests at no additional charge. All salmon-rich streams and abundant wildlife. aircraft are equipped with state of the art Departs: 9:45 AM You'll stop along the way to soak up the The aircraft is equipped with a digital stereo avionics and digital stereo sound systems. Approximately 3¼ Hours Adult $199.95; Child $149.95 grandeur and beauty of this lush land. sound system and headsets for each Rain ponchos and bottled water are available. individual guest to enjoy the narration. Each Dress warmly in layers. Wear a hat or beanie; Enjoy a snack and beverage; then drivers and participant is guaranteed a window seat and bring gloves and a scarf. This tour is not passengers have the opportunity to switch the pilot will identify points of interest en recommended for guests with physical positions for the return trip. -

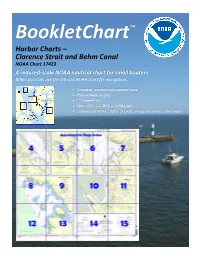

Bookletchart™ Harbor Charts – Clarence Strait and Behm Canal NOAA Chart 17423

BookletChart™ Harbor Charts – Clarence Strait and Behm Canal NOAA Chart 17423 A reduced-scale NOAA nautical chart for small boaters When possible, use the full-size NOAA chart for navigation. Included Area Published by the Revillagigedo Island. (See 334.1275, chapter 2, for limits/regulations.) Currents.–The flood current enters Behm Canal at each end and meets National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration somewhere in the vicinity of Burroughs Bay. In general the currents are National Ocean Service not very strong, ordinarily from 1 to 1.4 knots. Tide rips generally occur Office of Coast Survey on the ebb at the mouths of the various tributaries. During the ebb a strong W set is noticed in Behm Canal at the entrance to Naha Bay. (See www.NauticalCharts.NOAA.gov the Tidal Current Tables for daily predictions in Behm Canal.) In the early 888-990-NOAA summer, milky colored water extends from Burroughs Bay to the W end of Gedney Island and up into Yes Bay. This is the result of the glacial silt What are Nautical Charts? carried down by the rivers emptying into Burroughs Bay. The cove E of Roe Point, on the E shore, is a fair anchorage for small Nautical charts are a fundamental tool of marine navigation. They show craft in 5 to 10 fathoms, soft bottom. water depths, obstructions, buoys, other aids to navigation, and much Indian Point marks the N entrance to Naha Bay. The country N of the more. The information is shown in a way that promotes safe and point is heavily wooded. -

Geologic Map of the Ketchikan and Prince Rupert Quadrangles, Southeastern Alaska

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP I-1807 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE KETCHIKAN AND PRINCE RUPERT QUADRANGLES, SOUTHEASTERN ALASKA By Henry C. Berg, Raymond L. Elliott, and Richard D. Koch INTRODUCTION This pamphlet and accompanying map sheet describe the geology of the Ketchikan and Prince Rupert quadrangles in southeastern Alaska (fig. 1). The report is chiefly the result of a reconnaissance investigation of the geology and mineral re sources of the quadrangles by the U.S. Geological Survey dur ing 1975-1977 (Berg, 1982; Berg and others, 1978 a, b), but it also incorporates the results of earlier work and of more re cent reconnaissance and topical geologic studies in the area (fig. 2). We gratefully acknowledge the dedicated pioneering photointerpretive studies by the late William H. (Hank) Con don, who compiled the first 1:250,000-scale reconnaissance geologic map (unpublished) of the Ketchikan quadrangle in the 1950's and who introduced the senior author to the study 130' area in 1956. 57'L__r-'-'~~~;:::::::,~~.::::r----, Classification and nomenclature in this report mainly fol low those of Turner (1981) for metamorphic rocks, Turner and Verhoogen (1960) for plutonic rocks, and Williams and others (1982) for sedimentary rocks and extrusive igneous rocks. Throughout this report we assign metamorphic ages to various rock units and emplacement ages to plutons largely on the basis of potassium-argon (K-Ar) and lead-uranium (Pb-U) (zircon) isotopic studies of rocks in the Ketchikan and Prince Rupert quadrangles (table 1) and in adjacent areas. Most of the isotopic studies were conducted in conjunction with recon naissance geologic and mineral resource investigations and re 0 100 200 KILOMETER sulted in the valuable preliminary data that we cite throughout our report. -

Estimates of Crustal Assimilation in Quaternary Lavas from the Northern Cordillera, British Columbia

275 The Canadian Mineralogist Vol. 39, pp. 275-297 (2000) ESTIMATES OF CRUSTAL ASSIMILATION IN QUATERNARY LAVAS FROM THE NORTHERN CORDILLERA, BRITISH COLUMBIA JAMES K. RUSSELL§ Igneous Petrology Laboratory, Earth & Ocean Sciences, The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia V6T 1Z4, Canada STEINUNN HAUKSDÓTTIR National Energy Authority, Grensasvegur 9, Reykjavik, IS-108, Iceland ABSTRACT The region between the Iskut and Unuk rivers and immediately south of Hoodoo Mountain in northwestern British Columbia is host to eight distinct occurrences of Quaternary volcanic rocks comprising alkali olivine basalt and minor hawaiite. The centers range in age from 70, 000 to ~150 years B.P. This volcanic field, called herein the Iskut volcanic field, lies along the southern boundary of the Northern Cordilleran volcanic province (NCVP) and includes sites identified as: Iskut River, Tom MacKay Creek, Snippaker Creek, Cone Glacier, Cinder Mountain, King Creek, Second Canyon and Lava Fork. The lavas are olivine- and plagioclase-phyric, contain rare corroded grains of augite, and commonly entrain crustal xenoliths and xenocrysts. Many crustally derived xenoliths are partially fused. Petrological modeling shows that the major-element compositional variations of lavas within the individual centers cannot be accounted for by simple sorting of the olivine and plagioclase phenocrysts or even cryptic fractionation of higher-pressure pyroxene. Textural and mineralogical features combined with whole-rock chemical data suggest that assimilation of the underlying Cordilleran crust has affected the evolution of the relevant magmas. Mass-balance models are used to test the extent to which the within-center chemical variations are consistent with coupled crystallization and assimilation. On the basis of our analysis of four centers, the average ratio of assimilation to crystallization for the Iskut volcanic field is 1:2, suggesting that assimilation has played a greater role in the origins of NCVP lavas than recognized previously. -

ALASKA ALASKA Our Lifestyle, Your Reward

keTCHIKAN ALASKA ALASKA Our lifestyle, your reward. TRIP PLANNER 2016 TOURS THE ARTS SHOPPING SPORTFISHING NATIVE CULTURE ACCOMMODATIONS www.visit-ketchikan.com Our lifestyle, your reward Whether you’re planning your first visit to our unique corner of Alaska or coming back to enjoy more, we offer a hearty welcome to Ketchikan, where Alaska begins. This Trip Planner provides you with resources to make the most of your time in our region. If you don’t find what you’re looking for, just call our Visitor Information Center. We’ll help you plan the best possible Ketchikan experience. That’s what we’re here for. WHERE IN THE WORLD IS KETCHIKAN? You’ll reach our island community by sea or by air. We’re about 700 miles northwest of Seattle. The spectacular sea route takes you through the famed Inside Passage waterway of the North Pacific Ocean. Ketchikan is a popular destination for sportfishers, adventurers, cruise travelers and everyone who wants to break away from everyday life to experience a one-of-a-kind lifestyle. Here in the heart of Tongass National Forest, there’s plenty of beautiful country and shore to explore. Whether you visit us for a day or stay for an extended, independent adventure, our town is yours to discover and yours to love. 2 CONTENTS Planning Your Stay ............4-7 Accommodations ............8-10 Dining, Entertainment & Activities ................. 11 One-Stop Tour Center .......12-13 Can’t-Miss Attractions ........14-18 Meeting Planning & Facilities ... 19 Nature & Wildlife ...........20-21 Misty Fjords & Tongass National Forest ..... 22 Native Culture .............24-25 Arts & Culture ..............26-27 Sightseeing – Tours & Activities ...........