Alexander Archipelago Wolf: a Conservation Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wilderness in Southeastern Alaska: a History

Wilderness in Southeastern Alaska: A History John Sisk Today, Southeastern Alaska (Southeast) is well known remoteness make it wild in the most definitive sense. as a place of great scenic beauty, abundant wildlife and The Tongass encompasses 109 inventoried roadless fisheries, and coastal wilderness. Vast expanses of areas covering 9.6 million acres (3.9 million hectares), wild, generally undeveloped rainforest and productive and Congress has designated 5.8 million acres (2.3 coastal ecosystems are the foundation of the region’s million hectares) of wilderness in the nation’s largest abundance (Fig 1). To many Southeast Alaskans, (16.8 million acre [6.8 million hectare]) national forest wilderness means undisturbed fish and wildlife habitat, (U.S. Forest Service [USFS] 2003). which in turn translates into food, employment, and The Wilderness Act of 1964 provides a legal business. These wilderness values are realized in definition for wilderness. As an indicator of wild subsistence, sport and commercial fisheries, and many character, the act has ensured the preservation of facets of tourism and outdoor recreation. To Americans federal lands displaying wilderness qualities important more broadly, wilderness takes on a less utilitarian to recreation, science, ecosystem integrity, spiritual value and is often described in terms of its aesthetic or values, opportunities for solitude, and wildlife needs. spiritual significance. Section 2(c) of the Wilderness Act captures the essence of wilderness by identifying specific qualities that make it unique. The provisions suggest wilderness is an area or region characterized by the following conditions (USFS 2002): Section 2(c)(1) …generally appears to have been affected primarily by the forces of nature, with the imprint of man’s work substantially unnoticeable; Section 2(c)(2) …has outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation; Section 2(c)(3) …has at least five thousand acres of land or is of sufficient FIG 1. -

Brown Bear (Ursus Arctos) John Schoen and Scott Gende Images by John Schoen

Brown Bear (Ursus arctos) John Schoen and Scott Gende images by John Schoen Two hundred years ago, brown (also known as grizzly) bears were abundant and widely distributed across western North America from the Mississippi River to the Pacific and from northern Mexico to the Arctic (Trevino and Jonkel 1986). Following settlement of the west, brown bear populations south of Canada declined significantly and now occupy only a fraction of their original range, where the brown bear has been listed as threatened since 1975 (Servheen 1989, 1990). Today, Alaska remains the last stronghold in North America for this adaptable, large omnivore (Miller and Schoen 1999) (Fig 1). Brown bears are indigenous to Southeastern Alaska (Southeast), and on the northern islands they occur in some of the highest-density FIG 1. Brown bears occur throughout much of southern populations on earth (Schoen and Beier 1990, Miller et coastal Alaska where they are closely associated with salmon spawning streams. Although brown bears and grizzly bears al. 1997). are the same species, northern and interior populations are The brown bear in Southeast is highly valued by commonly called grizzlies while southern coastal populations big game hunters, bear viewers, and general wildlife are referred to as brown bears. Because of the availability of abundant, high-quality food (e.g. salmon), brown bears enthusiasts. Hiking up a fish stream on the northern are generally much larger, occur at high densities, and have islands of Admiralty, Baranof, or Chichagof during late smaller home ranges than grizzly bears. summer reveals a network of deeply rutted bear trails winding through tunnels of devil’s club (Oplopanx (Klein 1965, MacDonald and Cook 1999) (Fig 2). -

Admiralty Island National Monument

ADMIRALTY ISLAND NATIONAL MONUMENT DESCRIPTION At a glance: Admiralty Island National Monument (NM) is located on Admiralty Island NM quick facts Admiralty Island, 15 miles southwest of Juneau in south- east Alaska, and is accessible only by water or air. The Date established: Dec. 1, 1978; Dec. 2, 1980 island is characterized by rugged coastline, remote old growth rainforest, towering mountains, and alpine tundra Established by: Presidential proclamation, President with permanent icefields. It hosts the largest concentration Jimmy Carter (1978); Congressional designation, Public of brown bears and nesting bald eagles in the world, as Law 96-487 (1980) well as harbor seals, porpoises and sea lions, humpback Forest Service region: 10, Alaska Region whales, and all five species of Pacific salmon in its waters. More than 90 percent of the monument is designated as State: Alaska the Kootznoowoo Wilderness, nearly 1 million acres. Ad- Associated national forest: Tongass miralty Island has been the home to the Tlingít people for approximately 10,000 years. The monument area continues Total Forest Service acres: 997,226 to provide subsistence for these Alaskan Natives. Angoon, Reasons designated: “archaeological, cultural, and Admiralty Island’s only permanent community, continues historical resources, ecological and scientific value” to be an important cultural base. (Presidential Proclamation, 1978) BACKGROUND The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANSCA) of 1971 honored the rights of Alaska Natives to select approxi- People and visitors mately 44 million acres of Federal land in Alaska and au- thorized the Secretary of the Interior to withdraw 80 mil- Nearest metropolitan area: no metro areas within lion acres of land to be studied for possible additions to 500 miles the National Park, Wildlife Refuge, Wild and Scenic Rivers, and National Forest systems. -

Northwest Coast Archaeology

ANTH 442/542 - Northwest Coast Archaeology COURSE DESCRIPTION This course examines the more than 12,000 year old archaeological record of the Northwest Coast of North America, the culture area extending from southeast Alaska to coastal British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and northern California. This region has fascinated anthropologists for almost 150 years because its indigenous peoples have developed distinctive cultures based on fishing, hunting, and gathering economies. We begin by establishing the ecological and ethnographic background for the region, and then study how these have shaped archaeologists' ideas about the past. We study the contents of sites and consider the relationship between data, interpretation, and theory. Throughout the term, we discuss the dynamics of contact and colonialism and how these have impacted understandings of the recent and more distant pasts of these societies. This course will prepare you to understand and evaluate Northwest Coast archaeological news within the context of different jurisdictions. You will also have the opportunity to visit some archaeological sites on the Oregon coast. I hope the course will prepare you for a lifetime of appreciating Northwest Coast archaeology. WHERE AND WHEN Class: 10-11:50 am, Monday & Wednesday in Room 204 Condon Hall. Instructor: Dr. Moss Office hours: after class until 12:30 pm, and on Friday, 1:30-3:00 pm or by appointment 327 Condon, 346-6076; [email protected] REQUIRED READING: Moss, Madonna L. 2011 Northwest Coast: Archaeology as Deep History. SAA Press, Washington, D.C. All journal articles/book chapters in the “Course Readings” Module on Canvas. Please note that all royalties from the sale of this book go to the Native American Scholarship Fund of the Society for American Archaeology. -

Food Habits of Brown Bears on Northern Admiralty Island In

FOOD HABITS OF BROWN BEARS ON NORTHERN ADMl,RALTY · I SLANP. , SOUTHEAST.~LASKA ·A THESIS. Presented -to ~he Faculty of the University of Alaska in Partial Fulfillment o·f the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENGE By Thomas M. McCarthy,· }).S. F.iirbanks; Alaska December-1989 FOOD HAB~TS OF BROWN BEARS ON NORTHERN ADMIRALTY ISLAND, SOUTHEAST ALASKA By Thomas Michael McCarthy RECOMMENDED: APPROVED: FOOD HAB.rrs ()F B~QWN BEARS ON NORTHERN A1)~~llAL'J:'Y ··IS.LANl;);. SOtrrliEA&T .'~S~· ·A THESIS Presented ·tro 'the Faculty of the University of Alaska in Partial Fulfillment o£ the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENGE By Thomas.M. McCarthy,· ~.s. Fairbanks, ·Alaska · D~cember·1989 ABSTRACT The food habits of brown bears on northern Admiralty Island in Southeast Alaska were studied through analysis of fecal samples collected in 1984 and 1985. The diets of two groups of bears were examined, those that used low elevation habitats and anadromous fish streams, and those that remained at higher elevations throughout the year. Selected forage items observed in the diets were analyzed for nutrient content. While most bears used the protein-rich salmon resource, bears at high elevations substituted deer, small mammals, and plant species and parts high in nitrogen. Both groups of bears appeared to seek a high energy diet during the fall pre-denning period. In the second phase of the study, captive brown bears were used in feeding trials to determine the digestibilities of 4 natural forages; sedge (Garex lyngbyaei), skunk cabbage (Lysichitum americanum), devil's club berries (Oplopanax horridus), and salmon (Oncorhynchus sp.). -

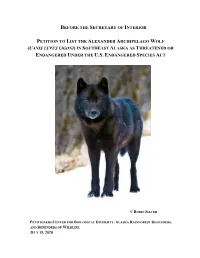

Petition to List the Alexander Archipelago Wolf in Southeast

BEFORE THE SECRETARY OF INTERIOR PETITION TO LIST THE ALEXANDER ARCHIPELAGO WOLF (CANIS LUPUS LIGONI) IN SOUTHEAST ALASKA AS THREATENED OR ENDANGERED UNDER THE U.S. ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT © ROBIN SILVER PETITIONERS CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY, ALASKA RAINFOREST DEFENDERS, AND DEFENDERS OF WILDLIFE JULY 15, 2020 NOTICE OF PETITION David Bernhardt, Secretary U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Margaret Everson, Principal Deputy Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Gary Frazer, Assistant Director for Endangered Species U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1840 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Greg Siekaniec, Alaska Regional Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1011 East Tudor Road Anchorage, AK 99503 [email protected] PETITIONERS Shaye Wolf, Ph.D. Larry Edwards Center for Biological Diversity Alaska Rainforest Defenders 1212 Broadway P.O. Box 6064 Oakland, California 94612 Sitka, Alaska 99835 (415) 385-5746 (907) 772-4403 [email protected] [email protected] Randi Spivak Patrick Lavin, J.D. Public Lands Program Director Defenders of Wildlife Center for Biological Diversity 441 W. 5th Avenue, Suite 302 (310) 779-4894 Anchorage, AK 99501 [email protected] (907) 276-9410 [email protected] _________________________ Date this 15 day of July 2020 2 Pursuant to Section 4(b) of the Endangered Species Act (“ESA”), 16 U.S.C. §1533(b), Section 553(3) of the Administrative Procedures Act, 5 U.S.C. § 553(e), and 50 C.F.R. § 424.14(a), the Center for Biological Diversity, Alaska Rainforest Defenders, and Defenders of Wildlife petition the Secretary of the Interior, through the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (“USFWS”), to list the Alexander Archipelago wolf (Canis lupus ligoni) in Southeast Alaska as a threatened or endangered species. -

Alaska Region New Employee Orientation Front Cover Shows Employees Working in Various Ways Around the Region

Forest Service UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Alaska Region | September 2021 Alaska Region New Employee Orientation Front cover shows employees working in various ways around the region. Alaska Region New Employee Orientation R10-UN-017 September 2021 Juneau’s typically temperate, wet weather is influenced by the Japanese Current and results in about 300 days a year with rain or moisture. Average rainfall is 92 inches in the downtown area and 54 inches ten miles away at the airport. Summer temperatures range between 45 °F and 65 °F (7 °C and 18 °C), and in the winter between 25 °F and 35 °F (-4 °C and -2 °C). On average, the driest months of the year are April and May and the wettest is October, with the warmest being July and the coldest January and February. Table of Contents National Forest System Overview ............................................i Regional Office .................................................................. 26 Regional Forester’s Welcome ..................................................1 Regional Leadership Team ........................................... 26 Alaska Region Organization ....................................................2 Acquisitions Management ............................................ 26 Regional Leadership Team (RLT) ............................................3 Civil Rights ................................................................... 26 Common Place Names .............................................................4 Ecosystems Planning and Budget ................................ -

Auke Lake Watershed Assessment Auke Lake Watershed in Juneau, Alaska

Auke Lake Watershed Assessment Auke Lake Watershed in Juneau, Alaska Prepared by the Juneau Watershed Partnership April 2009 The Juneau Watershed Partnership (JWP) is a nonprofit organization whose mission is to promote watershed integrity in the City and Borough of Juneau through education, research, and communication while encouraging sustainable use and development. Statement of Need and Purpose Situated approximately 12 miles north of Juneau, Alaska, Auke Lake is an anadromous system supporting coho, sockeye, pink and chum salmon, as well as cutthroat trout, rainbow trout and Dolly Varden char (Bethers, 1996). The Auke Lake watershed is a popular recreational area for Juneau residents, serves as a backdrop for the University of Alaska-Southeast campus, is a growing residential area, and hosts a NOAA/NMFS research facility on its outlet. The purpose of this watershed assessment is to compile existing data into a single document, in order to identify data gaps and provide recommendations for further studies. This document also provides the City and Borough of Juneau (CBJ) and the public with an overview of the current condition of the Auke Lake watershed, and outlines management recommendations to ensure the sustainability of fish habitat and recreational and aesthetic values. The results of this assessment should be used to guide watershed management of this valuable lake system. The intention is that this report will be utilized by CBJ staff, the CBJ Planning Commission, Wetlands Review Board, the City Assembly, as well as Juneau residents and local, state and federal agencies involved in conservation and land management decisions within the Auke Lake watershed. -

Development of a Macroinvertebrate Biological Assessment Index for Alexander Archipelago Streams – Final Report

Development of a Macroinvertebrate Biological Assessment Index for Alexander Archipelago Streams – Final Report by Daniel J. Rinella, Daniel L. Bogan, and Keiko Kishaba Environment and Natural Resources Institute University of Alaska Anchorage 707 A Street, Anchorage, AK 99501 and Benjamin Jessup Tetra Tech, Inc. 400 Red Rock Boulevard, Suite 200 Owings Mills, MD 21117 for Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation Division of Air & Water Quality 555 Cordova Street, Anchorage, AK 99501 2005 1 Acknowledgments The authors extend their gratitude to the federal, state, and local governments; agencies; tribes; volunteer professional biologists; watershed groups; and private citizens that have supported this project. We thank Kim Hastings of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for coordinating lodging and transportation in Juneau and for use of the research vessels Curlew and Surf Bird. We thank Neil Stichert, Joe McClung, and Deb Rudis, also of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, for field assistance. We thank the U.S. Forest Service for lodging and transportation across the Tongass National Forest; specifically, we thank Julianne Thompson, Emil Tucker, Ann Puffer, Tom Cady, Aaron Prussian, Jim Beard, Steve Paustian, Brandy Prefontaine, and Sue Farzan for coordinating support and for field assistance and Liz Cabrera for support with the Southeast Alaska GIS Library. We thank Jack Gustafson of the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Cathy Needham of the Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska and POWTEC, John Hudson of the USFS Forestry Science Lab, Mike Crotteau of the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation, and Bruce Johnson of the Alaska Department of Natural Resources for help with field data collection, logistics and local expertise. -

VIOLENCE, CAPTIVITY, and COLONIALISM on the NORTHWEST COAST, 1774-1846 by IAN S. URREA a THESIS Pres

“OUR PEOPLE SCATTERED:” VIOLENCE, CAPTIVITY, AND COLONIALISM ON THE NORTHWEST COAST, 1774-1846 by IAN S. URREA A THESIS Presented to the University of Oregon History Department and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts September 2019 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Ian S. Urrea Title: “Our People Scattered:” Violence, Captivity, and Colonialism on the Northwest Coast, 1774-1846 This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the History Department by: Jeffrey Ostler Chairperson Ryan Jones Member Brett Rushforth Member and Janet Woodruff-Borden Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2019 ii © 2019 Ian S. Urrea iii THESIS ABSTRACT Ian S. Urrea Master of Arts University of Oregon History Department September 2019 Title: “Our People Scattered:” Violence, Captivity, and Colonialism on the Northwest Coast, 1774-1846” This thesis interrogates the practice, economy, and sociopolitics of slavery and captivity among Indigenous peoples and Euro-American colonizers on the Northwest Coast of North America from 1774-1846. Through the use of secondary and primary source materials, including the private journals of fur traders, oral histories, and anthropological analyses, this project has found that with the advent of the maritime fur trade and its subsequent evolution into a land-based fur trading economy, prolonged interactions between Euro-American agents and Indigenous peoples fundamentally altered the economy and practice of Native slavery on the Northwest Coast. -

Geologic Map of the Ketchikan and Prince Rupert Quadrangles, Southeastern Alaska

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP I-1807 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE KETCHIKAN AND PRINCE RUPERT QUADRANGLES, SOUTHEASTERN ALASKA By Henry C. Berg, Raymond L. Elliott, and Richard D. Koch INTRODUCTION This pamphlet and accompanying map sheet describe the geology of the Ketchikan and Prince Rupert quadrangles in southeastern Alaska (fig. 1). The report is chiefly the result of a reconnaissance investigation of the geology and mineral re sources of the quadrangles by the U.S. Geological Survey dur ing 1975-1977 (Berg, 1982; Berg and others, 1978 a, b), but it also incorporates the results of earlier work and of more re cent reconnaissance and topical geologic studies in the area (fig. 2). We gratefully acknowledge the dedicated pioneering photointerpretive studies by the late William H. (Hank) Con don, who compiled the first 1:250,000-scale reconnaissance geologic map (unpublished) of the Ketchikan quadrangle in the 1950's and who introduced the senior author to the study 130' area in 1956. 57'L__r-'-'~~~;:::::::,~~.::::r----, Classification and nomenclature in this report mainly fol low those of Turner (1981) for metamorphic rocks, Turner and Verhoogen (1960) for plutonic rocks, and Williams and others (1982) for sedimentary rocks and extrusive igneous rocks. Throughout this report we assign metamorphic ages to various rock units and emplacement ages to plutons largely on the basis of potassium-argon (K-Ar) and lead-uranium (Pb-U) (zircon) isotopic studies of rocks in the Ketchikan and Prince Rupert quadrangles (table 1) and in adjacent areas. Most of the isotopic studies were conducted in conjunction with recon naissance geologic and mineral resource investigations and re 0 100 200 KILOMETER sulted in the valuable preliminary data that we cite throughout our report. -

Chapter 3: Brown Bear Management Report. Brown Bear Management

SPECIES Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Wildlife Conservation 907-465-4190 –PO Box 115526 MANAGEMENT REPORT Juneau, AK 99811-5526 CHAPTER 3: BROWN BEAR MANAGEMENT REPORT From: 1 July 2012 To: 30 June 2014 LOCATION 2 GAME MANAGEMENT UNIT: Unit 4 (5,820 mi ) GEOGRAPHIC DESCRIPTION: Admiralty, Baranof, Chichagof, and adjacent islands BACKGROUND Brown bears in Southeast Alaska inhabit all areas in Game Management Unit 4 (including Admiralty, Baranof, Chichagof, Kruzof, Yakobi, and Catherine islands). The population has been isolated from mainland brown/grizzly bear populations for more than 40,000 years and is genetically distinct from other bears (Heaton et al. 1996; Talbot and Shields 1996). Extensive brown bear research has been conducted on Admiralty and Chichagof islands from the early 1980s through 2004 (Schoen and Beier 1990; Titus and Beier 1993; Flynn et al. 2007). Management of Unit 4 brown bears has a colorful and controversial past. In the early part of the twentieth century, there were advocates for both complete elimination of and for more reasonable conservation of brown bears. Market hunting for hides and the calls for elimination of bears were gradually overcome by support for greater protection of the valuable bear resource. As a result, the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G) developed more restrictive harvest regulations for brown bears in Unit 4 (ADF&G 1998). Brown bear sealing requirements were established in Alaska in 1961. Since 1989, hunters have also been required to obtain registration permits before hunting brown bears in Unit 4 (ADF&G 1998). Prior to 1989, hunters were only required to obtain a hunting license and metal-locking big game tag.