Wilderness in Southeastern Alaska: a History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VGP) Version 2/5/2009

Vessel General Permit (VGP) Version 2/5/2009 United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) VESSEL GENERAL PERMIT FOR DISCHARGES INCIDENTAL TO THE NORMAL OPERATION OF VESSELS (VGP) AUTHORIZATION TO DISCHARGE UNDER THE NATIONAL POLLUTANT DISCHARGE ELIMINATION SYSTEM In compliance with the provisions of the Clean Water Act (CWA), as amended (33 U.S.C. 1251 et seq.), any owner or operator of a vessel being operated in a capacity as a means of transportation who: • Is eligible for permit coverage under Part 1.2; • If required by Part 1.5.1, submits a complete and accurate Notice of Intent (NOI) is authorized to discharge in accordance with the requirements of this permit. General effluent limits for all eligible vessels are given in Part 2. Further vessel class or type specific requirements are given in Part 5 for select vessels and apply in addition to any general effluent limits in Part 2. Specific requirements that apply in individual States and Indian Country Lands are found in Part 6. Definitions of permit-specific terms used in this permit are provided in Appendix A. This permit becomes effective on December 19, 2008 for all jurisdictions except Alaska and Hawaii. This permit and the authorization to discharge expire at midnight, December 19, 2013 i Vessel General Permit (VGP) Version 2/5/2009 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, 2008 William K. Honker, Acting Director Robert W. Varney, Water Quality Protection Division, EPA Region Regional Administrator, EPA Region 1 6 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, 2008 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, Barbara A. -

Brown Bear (Ursus Arctos) John Schoen and Scott Gende Images by John Schoen

Brown Bear (Ursus arctos) John Schoen and Scott Gende images by John Schoen Two hundred years ago, brown (also known as grizzly) bears were abundant and widely distributed across western North America from the Mississippi River to the Pacific and from northern Mexico to the Arctic (Trevino and Jonkel 1986). Following settlement of the west, brown bear populations south of Canada declined significantly and now occupy only a fraction of their original range, where the brown bear has been listed as threatened since 1975 (Servheen 1989, 1990). Today, Alaska remains the last stronghold in North America for this adaptable, large omnivore (Miller and Schoen 1999) (Fig 1). Brown bears are indigenous to Southeastern Alaska (Southeast), and on the northern islands they occur in some of the highest-density FIG 1. Brown bears occur throughout much of southern populations on earth (Schoen and Beier 1990, Miller et coastal Alaska where they are closely associated with salmon spawning streams. Although brown bears and grizzly bears al. 1997). are the same species, northern and interior populations are The brown bear in Southeast is highly valued by commonly called grizzlies while southern coastal populations big game hunters, bear viewers, and general wildlife are referred to as brown bears. Because of the availability of abundant, high-quality food (e.g. salmon), brown bears enthusiasts. Hiking up a fish stream on the northern are generally much larger, occur at high densities, and have islands of Admiralty, Baranof, or Chichagof during late smaller home ranges than grizzly bears. summer reveals a network of deeply rutted bear trails winding through tunnels of devil’s club (Oplopanx (Klein 1965, MacDonald and Cook 1999) (Fig 2). -

Public Law 96-487 (ANILCA)

APPENDlX - ANILCA 587 94 STAT. 2418 PUBLIC LAW 96-487-DEC. 2, 1980 16 usc 1132 (2) Andreafsky Wilderness of approximately one million note. three hundred thousand acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "Yukon Delta National Wildlife Refuge" dated April 1980; 16 usc 1132 {3) Arctic Wildlife Refuge Wilderness of approximately note. eight million acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "ArcticNational Wildlife Refuge" dated August 1980; (4) 16 usc 1132 Becharof Wilderness of approximately four hundred note. thousand acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "BecharofNational Wildlife Refuge" dated July 1980; 16 usc 1132 (5) Innoko Wilderness of approximately one million two note. hundred and forty thousand acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "Innoko National Wildlife Refuge", dated October 1978; 16 usc 1132 (6} Izembek Wilderness of approximately three hundred note. thousand acres as �enerally depicted on a map entitied 16 usc 1132 "Izembek Wilderness , dated October 1978; note. (7) Kenai Wilderness of approximately one million three hundred and fifty thousand acres as generaJly depicted on a map entitled "KenaiNational Wildlife Refuge", dated October 16 usc 1132 1978; note. (8) Koyukuk Wilderness of approximately four hundred thousand acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "KoxukukNational Wildlife Refuge", dated July 1980; 16 usc 1132 (9) Nunivak Wilderness of approximately six hundred note. thousand acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "Yukon DeltaNational Wildlife Refuge", dated July 1980; 16 usc 1132 {10} Togiak Wilderness of approximately two million two note. hundred and seventy thousand acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "Togiak National Wildlife Refuge", dated July 16 usc 1132 1980; note. -

2018 Uncruise Adventures Brochure

October 2017 Adventure Cruises Define Your to April 2019 22 to 86 Guests Un-nessSM ALASKA | MEXICO | HAWAIIAN ISLANDS | COSTA RICA | PANAMÁ | GALÁPAGOS | COLUMBIA & SNAKE RIVERS | WASHINGTON | BRITISH COLUMBIA Contents Define Your Un-ness 3 Small Ships, BIG Adventures 5 Adventure 6 Place 8 Connection 10 Finding Our Un-ness 12 Unparalleled Value 14 Ready. Set. Go. 16 Theme Cruises 18 Wellness Cruises 20 Family Discoveries 22 Solo Travel 23 Groups & Charters 24 Sailing Calendar 26 COSTA RICA & PANAMÁ 28 MEXICO’S SEA OF CORTÉS 40 HAWAIIAN ISLANDS 48 GALÁPAGOS ISLANDS 56 COLUMBIA & SNAKE RIVERS 64 PACIFIC NORTHWEST 72 ALASKA 82 Life On Board 116 Wining & Dining 118 The Fleet 122 Small Ship Comparison 142 What’s Included 144 Reservation Information 145 Responsible Travel & Affiliations 146 Welcome Aboard 147 2 UnCruise.com Define Your Un-nessSM [uhn-nis] To break away from the masses. Challenge. Freely used to release, exemplify, or intensify a force or quality. To engage, connect, and explore unique places, oneself, and with others on a most uncommon adventure. Snapshot: I found my happy place. unique. 3 “Exceeded expectations. Thanks to the crew—you are fabulous. Only downside? My cheeks hurt from smiling. Awesome, fantastic!” -Nancy D; Silver Lake, NH (Alaska 2016) 4 UnCruise.com Snapshot: (L) Best to pack your Alaska tennis shoes. (R) Go with the flow. Small Ships, BIG Adventures A crew member shows you to your cabin. After a short time getting situated, gain your bearings with a spin around the ship. Then head to the lounge for a glass of bubbly and to meet your shipmates. -

Chuck River Wilderness Endicott River Wilderness Kootznoowoo

US DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FOREST SERVICE ALASKA REGION Klukwan Skagway TONGASS NATIONAL FOREST Ò 1:265,000 3 1.5 0 3 6 9 12 Miles 4.5 2.25 0 4.5 9 13.5 18 Kilometers [ Cities Congressionally Designated LUD II Areas and Monument Mainline Roads Wilderness/Monument Wilderness Other Road Canada Roaded Roadless National Park 2001 Roadless Areas National Wildlife Refuge Tongass 77 VCU AK Mental Health Trust Land Exchange Land Returned to NFS Non-Forest Service Land Selected by AK Mental Health Haines Development LUD* Tongass National Forest * Development LUDs include Timber Production, Modified Landscape, Scenic Viewshed, and Experimental Forest Map Disclaimer: The USDA Forest Service makes no warranty, expressed or implied, including the warranties of merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose, nor assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, reliability, completeness or utility of these geospatial data, or for the improper or incorrect use of these geospatial data. These geospatial data and related maps or graphics are not legal documents and are not intended to be used as such. The data and maps may not be used to determine title, ownership, legal descriptions or boundaries, legal jurisdiction, or restrictions that may be in place on either public or private land. Natural hazards may or may not be depicted on the data and maps, and land users should exercise due caution. The data are dynamic and may change over time. The user is responsible to verify the limitations of the geospatial data and to use the data accordingly and use constraints information. Map 2/6 Endicott River Wilderness Gustavus Pleasant/Lemusurier/Inian Islands Wilderness Elfin Cove Pelican Hoonah Juneau West Chichagof-Yakobi Wilderness Tenakee Springs Kootznoowoo Wilderness Angoon Tracy Arm-Fords Terror Wilderness Chuck River Wilderness Sitka Sources: Esri, GEBCO, NOAA, National Geographic, Garmin, HERE, Geonames.org, and other contributors, Esri, Garmin, GEBCO, NOAA NGDC, and other contributors. -

Steve Mccutcheon Collection, B1990.014

REFERENCE CODE: AkAMH REPOSITORY NAME: Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center Bob and Evangeline Atwood Alaska Resource Center 625 C Street Anchorage, AK 99501 Phone: 907-929-9235 Fax: 907-929-9233 Email: [email protected] Guide prepared by: Sara Piasecki, Archivist TITLE: Steve McCutcheon Collection COLLECTION NUMBER: B1990.014 OVERVIEW OF THE COLLECTION Dates: circa 1890-1990 Extent: approximately 180 linear feet Language and Scripts: The collection is in English. Name of creator(s): Steve McCutcheon, P.S. Hunt, Sydney Laurence, Lomen Brothers, Don C. Knudsen, Dolores Roguszka, Phyllis Mithassel, Alyeska Pipeline Services Co., Frank Flavin, Jim Cacia, Randy Smith, Don Horter Administrative/Biographical History: Stephen Douglas McCutcheon was born in the small town of Cordova, AK, in 1911, just three years after the first city lots were sold at auction. In 1915, the family relocated to Anchorage, which was then just a tent city thrown up to house workers on the Alaska Railroad. McCutcheon began taking photographs as a young boy, but it wasn’t until he found himself in the small town of Curry, AK, working as a night roundhouse foreman for the railroad that he set out to teach himself the art and science of photography. As a Deputy U.S. Marshall in Valdez in 1940-1941, McCutcheon honed his skills as an evidential photographer; as assistant commissioner in the state’s new Dept. of Labor, McCutcheon documented the cannery industry in Unalaska. From 1942 to 1944, he worked as district manager for the federal Office of Price Administration in Fairbanks, taking photographs of trading stations, communities and residents of northern Alaska; he sent an album of these photos to Washington, D.C., “to show them,” he said, “that things that applied in the South 48 didn’t necessarily apply to Alaska.” 1 1 Emanuel, Richard P. -

Occurrence of Wildlife on the Coronation and Spani'sh Islands

ALASKA DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND G~lli JUNEAU, ALASKA STATE OF ALASKA Bill Sheffield, Governor DEPARTMENT OF FISH 1\ND GA1-1E Don Collinsworth, Commissioner DIVISION OF GAME Lewis Pamplin, Director OCCURRENCE OF WILDLIFE ON THE CORONATION AND SPANI'SH ISLANDS. ALASKA BY Charles R. Land E. L. Young, Jr. Petersburg Area Report No. 84-1 1984 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section SUMMARY. 1 OBJECTIVES 2 BACKGROUND 3 C') STUDY AREA 3 ~ <0 C\1 0 PROCEDURES 7 C\1 ~ 0 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION 8 0 1.{) 1.{) RECOMMENDATIONS. 16 """'C') C') ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 17 LITERATURE CITED 18 FIGURES. 19 TABLES 21 APPENDIX 26 SUMMARY During the period of February to August 1983, a project was initiated to determine the status of the wildlife populations of Coronation Island. Hunting and trapping seasons have been closed for many years and deer and furbearer populations were of primary concern. Our studies indicate that the deer population is high and opening the season is recommended. There appeared to be numerous mink and river otters, and again, opening the season is advised. Forty-eight species of birds were identified during the study. Fourteen species were identified as known or probable nesters. No evidence of wolves was found on the island, although there was a transplant in the 1960's. Terrestrial mammals observed included Sitka black-tailed deer, mink, river otter, Sitka deer mouse, Coronation Island vole, and vagrant shrew. Sea otters were commonly observed and harbor seals and Steller sea lions were numerous. Humpback whales were seen in Aats Bay and Egg Harbor as well as offshore. -

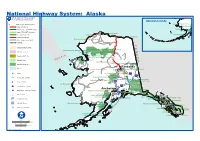

National Highway System: Alaska U.S

National Highway System: Alaska U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration Aleutian Islands Eisenhower Interstate System Lake Clark National Preserve Lake Clark Wilderness Other NHS Routes Non-Interstate STRAHNET Route Katmai National Preserve Katmai Wilderness Major STRAHNET Connector Lonely Distant Early Warning Station Intermodal Connector Wainwright Dew Station Aniakchak National Preserve Barter Island Long Range Radar Site Unbuilt NHS Routes Other Roads (not on NHS) Point Lay Distant Early Warning Station Railroad CC Census Urbanized Areas AA Noatak Wilderness Gates of the Arctic National Park Cape Krusenstern National Monument NN Indian Reservation Noatak National Preserve Gates of the Arctic Wilderness Kobuk Valley National Park AA Department of Defense Kobuk Valley Wilderness AA D II Gates of the Arctic National Preserve 65 D SSSS UU A National Forest RR Bering Land Bridge National Preserve A Indian Mountain Research Site Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve National Park Service College Fairbanks Water Campion Air Force Station Fairbanks Fortymile Wild And Scenic River Fort Wainwright Fort Greely (Scheduled to close) Airport A2 4 Denali National Park A1 Intercity Bus Terminal Denali National PreserveDenali Wilderness Wrangell-Saint Elias National Park and Preserve Tatalina Long Range Radar Site Wrangell-Saint Elias National Preserve Ferry Terminal A4 Cape Romanzof Long Range Radar Site Truck/Pipeline Terminal A1 Anchorage 4 Wrangell-Saint Elias Wilderness Multipurpose Passenger Facility Sparrevohn Long -

KMD Economic Feasibility

U. S. Department of the Interior SLM-Alaska Open File Report 68 Bureau of Land Management BLM/AK/ST-98/006+3090+930 February 1998 Alaska State Office 222 West 7th, #13 Anchorage, Alaska 99513 Economic Feasibility of Mining in the Chichagof and Baranof Islands Area, Southeast Alaska James R. Coldwell Author James R. Coldwell is a mining engineer in the Division of Lands, Minerals and Resources, working for the Juneau Mineral Resources Team, Bureau of Land Management, Juneau Alaska. Cover Photo Chichagof Mine, circa 1930, photograph by E. Andrews. From 1906-1942, the Chichagof Mine produced about 20,500 kg of gold from over 540,000 mt of ore. The mine closed in 1942 due to shortages of men and equipment created by World War II. Open File Reports Open File Reports identify the results of inventories or other investigations that are made available to the public outside the formal BLM-Alaska technical publication series. These reports can include preliminary or incomplete data and are not published and distributed in quantity. The reports are available at BLM offices in Alaska, and the USDI Resources Library in Anchorage, various libraries of the University of Alaska, and other selected locations. Copies are also available for inspection at the USDI Natural Resource Library in Washington, D.C. and at the BLM Service Center Library in Denver. Economic Feasibility of Mining in the Chichagof and Baranof Islands Area, Southeast Alaska James R. Coldwell Bureau of Land Management Alaska State Office Open File Report 68 Anchorage, Alaska 99513 February 1998 i CONTENTS Abstract.............................................................. 1 Introduction.......................................................... -

Straddling the Arctic Circle in the East Central Part of the State, Yukon Flats Is Alaska's Largest Interior Valley

Straddling the Arctic Circle in the east central part of the State, Yukon Flats is Alaska's largest Interior valley. The Yukon River, fifth largest in North America and 2,300 miles long from its source in Canada to its mouth in the Bering Sea, bisects the broad, level flood- plain of Yukon Flats for 290 miles. More than 40,000 shallow lakes and ponds averaging 23 acres each dot the floodplain and more than 25,000 miles of streams traverse the lowland regions. Upland terrain, where lakes are few or absent, is the source of drainage systems im- portant to the perpetuation of the adequate processes and wetland ecology of the Flats. More than 10 major streams, including the Porcupine River with its headwaters in Canada, cross the floodplain before discharging into the Yukon River. Extensive flooding of low- land areas plays a dominant role in the ecology of the river as it is the primary source of water for the many lakes and ponds of the Yukon Flats basin. Summer temperatures are higher than at any other place of com- parable latitude in North America, with temperatures frequently reaching into the 80's. Conversely, the protective mountains which make possible the high summer temperatures create a giant natural frost pocket where winter temperatures approach the coldest of any inhabited area. While the growing season is short, averaging about 80 days, long hours of sunlight produce a rich growth of aquatic vegeta- tion in the lakes and ponds. Soils are underlain with permafrost rang- ing from less than a foot to several feet, which contributes to pond permanence as percolation is slight and loss of water is primarily due to transpiration and evaporation. -

Draft Small Vessel General Permit

ILLINOIS DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES, COASTAL MANAGEMENT PROGRAM PUBLIC NOTICE The United States Environmental Protection Agency, Region 5, 77 W. Jackson Boulevard, Chicago, Illinois has requested a determination from the Illinois Department of Natural Resources if their Vessel General Permit (VGP) and Small Vessel General Permit (sVGP) are consistent with the enforceable policies of the Illinois Coastal Management Program (ICMP). VGP regulates discharges incidental to the normal operation of commercial vessels and non-recreational vessels greater than or equal to 79 ft. in length. sVGP regulates discharges incidental to the normal operation of commercial vessels and non- recreational vessels less than 79 ft. in length. VGP and sVGP can be viewed in their entirety at the ICMP web site http://www.dnr.illinois.gov/cmp/Pages/CMPFederalConsistencyRegister.aspx Inquiries concerning this request may be directed to Jim Casey of the Department’s Chicago Office at (312) 793-5947 or [email protected]. You are invited to send written comments regarding this consistency request to the Michael A. Bilandic Building, 160 N. LaSalle Street, Suite S-703, Chicago, Illinois 60601. All comments claiming the proposed actions would not meet federal consistency must cite the state law or laws and how they would be violated. All comments must be received by July 19, 2012. Proposed Small Vessel General Permit (sVGP) United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) SMALL VESSEL GENERAL PERMIT FOR DISCHARGES INCIDENTAL TO THE NORMAL OPERATION OF VESSELS LESS THAN 79 FEET (sVGP) AUTHORIZATION TO DISCHARGE UNDER THE NATIONAL POLLUTANT DISCHARGE ELIMINATION SYSTEM In compliance with the provisions of the Clean Water Act, as amended (33 U.S.C. -

2008 ANNUAL REPORT SARAH PALIN, Governor

STATE OF ALASKA CITIZENS' ADVISORY COMMISSION ON FEDERAL AREAS 2008 ANNUAL REPORT SARAH PALIN, Governor 3700AIRPORT WAY CITIZENS' ADVISORY COMMISSION FAIRBANKS, ALASKA 99709 ON FEDERAL AREAS PHONE: (907) 374-3737 FAX: (907)451-2751 Dear Reader: This is the 2008 Annual Report of the Citizens' Advisory Commission on Federal Areas to the Governor and the Alaska State Legislature. The annual report is required by AS 41.37.220(f). INTRODUCTION The Citizens' Advisory Commission on Federal Areas was originally established by the State of Alaska in 1981 to provide assistance to the citizens of Alaska affected by the management of federal lands within the state. In 2007 the Alaska State Legislature reestablished the Commission. 2008 marked the first year of operation for the Commission since funding was eliminated in 1999. Following the 1980 passage of the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA), the Alaska Legislature identified the need for an organization that could provide assistance to Alaska's citizens affected by that legislation. ANILCA placed approximately 104 million acres of federal public lands in Alaska into conservation system units. This, combined with existing units, created a system of national parks, national preserves, national monuments, national wildlife refuges and national forests in the state encompassing more than 150 million acres. The resulting changes in land status fundamentally altered many Alaskans' traditional uses of these federal lands. In the 28 years since the passage of ANILCA, changes have continued. The Federal Subsistence Board rather than the State of Alaska has assumed primary responsibility for regulating subsistence hunting and fishing activities on federal lands.