THE STATUS and CONSERVATION of the ALEXANDER Archipelago WOLF in SOUTHEASTERN Alaska

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northwest Coast Archaeology

ANTH 442/542 - Northwest Coast Archaeology COURSE DESCRIPTION This course examines the more than 12,000 year old archaeological record of the Northwest Coast of North America, the culture area extending from southeast Alaska to coastal British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and northern California. This region has fascinated anthropologists for almost 150 years because its indigenous peoples have developed distinctive cultures based on fishing, hunting, and gathering economies. We begin by establishing the ecological and ethnographic background for the region, and then study how these have shaped archaeologists' ideas about the past. We study the contents of sites and consider the relationship between data, interpretation, and theory. Throughout the term, we discuss the dynamics of contact and colonialism and how these have impacted understandings of the recent and more distant pasts of these societies. This course will prepare you to understand and evaluate Northwest Coast archaeological news within the context of different jurisdictions. You will also have the opportunity to visit some archaeological sites on the Oregon coast. I hope the course will prepare you for a lifetime of appreciating Northwest Coast archaeology. WHERE AND WHEN Class: 10-11:50 am, Monday & Wednesday in Room 204 Condon Hall. Instructor: Dr. Moss Office hours: after class until 12:30 pm, and on Friday, 1:30-3:00 pm or by appointment 327 Condon, 346-6076; [email protected] REQUIRED READING: Moss, Madonna L. 2011 Northwest Coast: Archaeology as Deep History. SAA Press, Washington, D.C. All journal articles/book chapters in the “Course Readings” Module on Canvas. Please note that all royalties from the sale of this book go to the Native American Scholarship Fund of the Society for American Archaeology. -

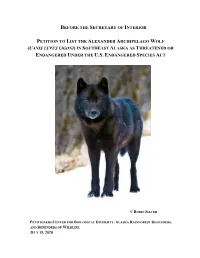

Petition to List the Alexander Archipelago Wolf in Southeast

BEFORE THE SECRETARY OF INTERIOR PETITION TO LIST THE ALEXANDER ARCHIPELAGO WOLF (CANIS LUPUS LIGONI) IN SOUTHEAST ALASKA AS THREATENED OR ENDANGERED UNDER THE U.S. ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT © ROBIN SILVER PETITIONERS CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY, ALASKA RAINFOREST DEFENDERS, AND DEFENDERS OF WILDLIFE JULY 15, 2020 NOTICE OF PETITION David Bernhardt, Secretary U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Margaret Everson, Principal Deputy Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Gary Frazer, Assistant Director for Endangered Species U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1840 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Greg Siekaniec, Alaska Regional Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1011 East Tudor Road Anchorage, AK 99503 [email protected] PETITIONERS Shaye Wolf, Ph.D. Larry Edwards Center for Biological Diversity Alaska Rainforest Defenders 1212 Broadway P.O. Box 6064 Oakland, California 94612 Sitka, Alaska 99835 (415) 385-5746 (907) 772-4403 [email protected] [email protected] Randi Spivak Patrick Lavin, J.D. Public Lands Program Director Defenders of Wildlife Center for Biological Diversity 441 W. 5th Avenue, Suite 302 (310) 779-4894 Anchorage, AK 99501 [email protected] (907) 276-9410 [email protected] _________________________ Date this 15 day of July 2020 2 Pursuant to Section 4(b) of the Endangered Species Act (“ESA”), 16 U.S.C. §1533(b), Section 553(3) of the Administrative Procedures Act, 5 U.S.C. § 553(e), and 50 C.F.R. § 424.14(a), the Center for Biological Diversity, Alaska Rainforest Defenders, and Defenders of Wildlife petition the Secretary of the Interior, through the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (“USFWS”), to list the Alexander Archipelago wolf (Canis lupus ligoni) in Southeast Alaska as a threatened or endangered species. -

Alaska Region New Employee Orientation Front Cover Shows Employees Working in Various Ways Around the Region

Forest Service UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Alaska Region | September 2021 Alaska Region New Employee Orientation Front cover shows employees working in various ways around the region. Alaska Region New Employee Orientation R10-UN-017 September 2021 Juneau’s typically temperate, wet weather is influenced by the Japanese Current and results in about 300 days a year with rain or moisture. Average rainfall is 92 inches in the downtown area and 54 inches ten miles away at the airport. Summer temperatures range between 45 °F and 65 °F (7 °C and 18 °C), and in the winter between 25 °F and 35 °F (-4 °C and -2 °C). On average, the driest months of the year are April and May and the wettest is October, with the warmest being July and the coldest January and February. Table of Contents National Forest System Overview ............................................i Regional Office .................................................................. 26 Regional Forester’s Welcome ..................................................1 Regional Leadership Team ........................................... 26 Alaska Region Organization ....................................................2 Acquisitions Management ............................................ 26 Regional Leadership Team (RLT) ............................................3 Civil Rights ................................................................... 26 Common Place Names .............................................................4 Ecosystems Planning and Budget ................................ -

Development of a Macroinvertebrate Biological Assessment Index for Alexander Archipelago Streams – Final Report

Development of a Macroinvertebrate Biological Assessment Index for Alexander Archipelago Streams – Final Report by Daniel J. Rinella, Daniel L. Bogan, and Keiko Kishaba Environment and Natural Resources Institute University of Alaska Anchorage 707 A Street, Anchorage, AK 99501 and Benjamin Jessup Tetra Tech, Inc. 400 Red Rock Boulevard, Suite 200 Owings Mills, MD 21117 for Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation Division of Air & Water Quality 555 Cordova Street, Anchorage, AK 99501 2005 1 Acknowledgments The authors extend their gratitude to the federal, state, and local governments; agencies; tribes; volunteer professional biologists; watershed groups; and private citizens that have supported this project. We thank Kim Hastings of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for coordinating lodging and transportation in Juneau and for use of the research vessels Curlew and Surf Bird. We thank Neil Stichert, Joe McClung, and Deb Rudis, also of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, for field assistance. We thank the U.S. Forest Service for lodging and transportation across the Tongass National Forest; specifically, we thank Julianne Thompson, Emil Tucker, Ann Puffer, Tom Cady, Aaron Prussian, Jim Beard, Steve Paustian, Brandy Prefontaine, and Sue Farzan for coordinating support and for field assistance and Liz Cabrera for support with the Southeast Alaska GIS Library. We thank Jack Gustafson of the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Cathy Needham of the Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska and POWTEC, John Hudson of the USFS Forestry Science Lab, Mike Crotteau of the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation, and Bruce Johnson of the Alaska Department of Natural Resources for help with field data collection, logistics and local expertise. -

VIOLENCE, CAPTIVITY, and COLONIALISM on the NORTHWEST COAST, 1774-1846 by IAN S. URREA a THESIS Pres

“OUR PEOPLE SCATTERED:” VIOLENCE, CAPTIVITY, AND COLONIALISM ON THE NORTHWEST COAST, 1774-1846 by IAN S. URREA A THESIS Presented to the University of Oregon History Department and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts September 2019 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Ian S. Urrea Title: “Our People Scattered:” Violence, Captivity, and Colonialism on the Northwest Coast, 1774-1846 This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the History Department by: Jeffrey Ostler Chairperson Ryan Jones Member Brett Rushforth Member and Janet Woodruff-Borden Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2019 ii © 2019 Ian S. Urrea iii THESIS ABSTRACT Ian S. Urrea Master of Arts University of Oregon History Department September 2019 Title: “Our People Scattered:” Violence, Captivity, and Colonialism on the Northwest Coast, 1774-1846” This thesis interrogates the practice, economy, and sociopolitics of slavery and captivity among Indigenous peoples and Euro-American colonizers on the Northwest Coast of North America from 1774-1846. Through the use of secondary and primary source materials, including the private journals of fur traders, oral histories, and anthropological analyses, this project has found that with the advent of the maritime fur trade and its subsequent evolution into a land-based fur trading economy, prolonged interactions between Euro-American agents and Indigenous peoples fundamentally altered the economy and practice of Native slavery on the Northwest Coast. -

Geopolitics and Environment in the Sea Otter Trade

UC Merced UC Merced Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Soft gold and the Pacific frontier: geopolitics and environment in the sea otter trade Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/03g4f31t Author Ravalli, Richard John Publication Date 2009 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California 1 Introduction Covering over one-third of the earth‘s surface, the Pacific Basin is one of the richest natural settings known to man. As the globe‘s largest and deepest body of water, it stretches roughly ten thousand miles north to south from the Bering Straight to the Antarctic Circle. Much of its continental rim from Asia to the Americas is marked by coastal mountains and active volcanoes. The Pacific Basin is home to over twenty-five thousand islands, various oceanic temperatures, and a rich assortment of plants and animals. Its human environment over time has produced an influential civilizations stretching from Southeast Asia to the Pre-Columbian Americas.1 An international agreement currently divides the Pacific at the Diomede Islands in the Bering Strait between Russia to the west and the United States to the east. This territorial demarcation symbolizes a broad array of contests and resolutions that have marked the region‘s modern history. Scholars of Pacific history often emphasize the lure of natural bounty for many of the first non-natives who ventured to Pacific waters. In particular, hunting and trading for fur bearing mammals receives a significant amount of attention, perhaps no species receiving more than the sea otter—originally distributed along the coast from northern Japan, the Kuril Islands and the Kamchatka peninsula, east toward the Aleutian Islands and the Alaskan coastline, and south to Baja California. -

Tongass Archaeology Notes

United States Department of Agriculture Tongass Archaeology Notes Pictographs In Southeast Alaska By Martin V. Stanford There are two types of rock art in southeast Alaska’s Alexander Archipelago; petroglyphs and pictographs. Petroglyphs were pecked, chiseled or ground into boulders, cobbles or outcrops of bedrock which are usually located in the intertidal areas near salmon streams, fish camps or old villages. Pictographs (Figs. 1-4) on the other hand were painted onto rock walls above the shorelines of the ocean, lakes or rivers and are distributed over a large area, with some painted in very remote locations. This pattern suggests Figure 1: The pictograph are of a sun sign top, below a canoe that most pictographs with nine people, a circular face with three eyes and to the right were painted in the skeletonized human figure. spring, summer, or fall, during gathering and trading seasons, rather than near their winter villages, when weather and sea conditions were at their most challenging. Some pictographs may have been painted in these remote locations by shamans during their quests to obtain spirit helpers (yeik or yek). Forest Service Tongass National Forest R10-RG-226 August 2017 Alaska Region Tongass Archaeology Notes Recent studies show that pictographs are more common than previously thought (Stanford 2011). As of 2016 one hundred and twenty five pictographs have been reported in the state of Alaska with one hundred and eleven of these located in southeast Alaska. Most pictographs were painted on overhanging rock walls or other rock walls that are protected in some way from rain or snow. -

Subsistence Harvests and Trade of Pacific Herring Spawn on Macrocystis Kelp in Hydaburg, Alaska

Technical Paper No. 225 Subsistence Harvests and Trade of Pacific Herring Spawn on Macrocystis Kelp in Hydaburg, Alaska by Anne-Marie Victor-Howe February 2008 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Subsistence Symbols and Abbreviations The following symbols and abbreviations, and others approved for the Système International d'Unités (SI), are used without definition in the following reports by the Division of Subsistence. All others, including deviations from definitions listed below, are noted in the text at first mention, as well as in the titles or footnotes of tables, and in figure or figure captions. Weights and measures (metric) General Measures (fisheries) centimeter cm Alaska Administrative fork length FL deciliter dL Code AAC mideye-to-fork MEF gram g all commonly accepted mideye-to-tail-fork METF hectare ha abbreviations e.g., Mr., standard length SL kilogram kg Mrs., AM, PM, etc. total length TL kilometer km all commonly accepted liter L professional titles e.g., Dr., Mathematics, statistics meter m Ph.D., all standard mathematical milliliter mL R.N., etc. signs, symbols and millimeter mm at @ abbreviations compass directions: alternate hypothesis HA Weights and measures (English) east E base of natural logarithm e cubic feet per second ft3/s north N catch per unit effort CPUE foot ft south S coefficient of variation CV gallon gal west W common test statistics (F, t, χ2, inch in copyright © etc.) mile mi corporate suffixes: confidence interval CI nautical mile nmi Company Co. correlation coefficient ounce oz Corporation Corp. (multiple) R pound lb Incorporated Inc. correlation coefficient quart qt Limited Ltd. -

Assessment of Invasive Species in Alaska and Its National Forests August 30, 2005

Assessment of Invasive Species in Alaska and its National Forests August 30, 2005 Compiled by Barbara Schrader and Paul Hennon Contributing Authors: USFS Alaska Regional Office: Michael Goldstein, Wildlife Ecologist; Don Martin, Fisheries Ecologist; Barbara Schrader, Vegetation Ecologist USFS Alaska Region, State and Private Forestry/Forest Health Protection: Paul Hennon, Pathologist; Ed Holsten, Entomologist (retired); Jim Kruse, Entomologist Executive Summary This document assesses the current status of invasive species in Alaska’s ecosystems, with emphasis on the State’s two national forests. Lists of invasive species were developed in several taxonomic groups including plants, terrestrial and aquatic organisms, tree pathogens and insects. Sixty-three plant species have been ranked according to their invasive characteristics. Spotted knapweed, Japanese knotweed, reed canarygrass, white sweetclover, ornamental jewelweed, Canada thistle, bird vetch, orange hawkweed, and garlic mustard were among the highest-ranked species. A number of non-native terrestrial fauna species have been introduced or transplanted in Alaska. At this time only rats are considered to be causing substantial ecological harm. The impacts of non-native slugs in estuaries are unknown, and concern exists about the expansion of introduced elk populations in southeast Alaska. Northern pike represents the most immediate concern among aquatic species, but several other species (Atlantic salmon, Chinese mitten crab, and New Zealand mudsnail) could invade Alaska in the future. No tree pathogen is currently damaging Alaska’s native tree species but several fungal species from Europe and Asia could cause considerable damage if introduced. Four introduced insects are currently established and causing defoliation and tree mortality to spruce, birch, and larch. -

Units Featuring Tlingit Language, Culture and History Tlingit People Continue to Have a Great Understanding of the Environment

Grade Levels K-2 Tlingit Cultural Significance Tlingit people have occupied Southeast Alaska for thousands of years. Their tribal land covers a wide coastal region from Yakutat to Ketchikan. Tlingit people traditionally subsist on the area’s wealth of natural resources. A way of life suited to the resources and demands of the environment was adopted. Hunting activities were determined by the seasonal availability of local resources. A series of elementary level thematic units featuring Tlingit language, culture and history Tlingit people continue to have a great understanding of the environment. The were developed in Juneau, Alaska in 2004-6. techniques used to gather food have changed but subsistence hunting and fishing The project was funded by two grants from continue to be important today. the U.S. Department of Education, awarded to the Sealaska Heritage Institute (Boosting Food is a central aspect of Tlingit culture and the sea is an abundant provider. The Academic Achievement: Tlingit Language Immersion Program, grant #92-0081844) sea offers a bounty of animal life and supplies many foods. The types of foods eaten and the Juneau School District (Building on and methods of preparation have remained much the same over the years. Excellence, grant #S356AD30001). In order to respect the lives of the animals that are harvested, all parts of the animal are utilized in some way. For example, parts of many different sea mammals are Lessons and units were written by a team used in the making of at.óow, tools, and weapons. of teachers and specialists led by Nancy Douglas, Elementary Cultural Curriculum Coordinator, Juneau School District. -

Alexander Archipelago Wolf: a Conservation Assessment

United States Department of Agriculture The Alexander Archipelago Forest Service Wolf: A Conservation Pacific Northwest Research Station Assessment General Technical Report PNW-GTR-384 David K. Person, Matthew Kirchhoff, November 1996 Victor Van Ballenberghe, George C. Iverson, and Edward Grossman Authors DAVID K. PERSON is a graduate fellow, Alaska Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK 99775; MATTHEW KIRCHHOFF is a research wildlife biologist, Alaska Department of Fish and Game, P.O. Box 240020 Douglas, AK 99824; VICTOR VAN BALLENBERGHE is a research wildlife biologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, Forestry Sciences Laboratory, 3301 C Street, Suite 200, Anchorage, AK 99503-3954; GEORGE C. IVERSON is the regional ecology program leader, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Alaska Region, P.O. Box 21628, Juneau, AK 99801; and EDWARD GROSSMAN is a wildlife biologist with the U.S. Department of the Interior, Ecological Services, 3000 Vintage Boulevard Suite 205, Juneau, AK 99801. Conservation and Resource Assessments for the Tongass Land Management Plan Revision Charles G. Shaw III Technical Coordinator The Alexander Archipelago Wolf: A Conservation Assessment David K. Person Matthew Kirchhoff Victor Van Ballenberghe George C. Iverson Edward Grossman Published by: U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station Portland, Oregon General Technical Report PNW-GTR-384 November 1996 In cooperation with: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Alaska Department of Fish and Game Abstract Person, David K.; Kirchhoff, Matthew; Van Ballenberghe, Victor; Iverson, George C.; Grossman, Edward. 1996. The Alexander Archipelago wolf: a conservation assessment. -

First Record of the European Golden-Plover (Pluvialis Apricaria) from the Pacific

NOTES FIRST RECORD OF THE EUROPEAN GOLDEN-PLOVER (PLUVIALIS APRICARIA) FROM THE PACIFIC ANDREW W. PISTON, P.O. Box 6553, Ketchikan,Alaska 99901 STEVEN C. HEINL, P.O. Box 23101, Ketchikan,Alaska 99901 The EuropeanGolden-Plover (Pluvialis apricaria) breedsfrom Icelandand the BritishIsles east to the baseof the Taimyr Peninsula,Russia, at about 102 ø 30' E (Vaurie1965). Virtuallythe entirepopulation migrates to or throughEurope to winter in the BritishIsles, western Europe, and throughoutthe MediterraneanBasin; small numberswinter east to the southernCaspian Sea and casuallyto easternIndia, and smallnumbers winter on the Atlanticcoast of Africa,casually south to Gambia(Vaurie 1965, Cramp 1983). At the westernperiphery of this range,the EuropeanGolden- Ploveris a regularvagrant to Greenland,where it is alsoa localbreeder in the northeast (Boertmann1994). It is a casualvisitant to Newfoundland(including Labrador) and Saint Pierre et Miquelon, with nearly all recordsin April and May (Tuck 1968, Mactavish1988, ABA 1996). There are reportsfrom New Brunswick(Am. Birds[AB] 42: 408, 1988), Nova Scotia(AB 43:56, 1989; AB 44:390 1990; Natl. Audubon Soc. Field Notes [NASFN]49:222, 1995), and Quebec(AB 42:1271, 1988). On 14 January2001 we collecteda EuropeanGolden-Plover near the Ketchikan airport, GravinaIsland, Alexander Archipelago, southeast Alaska (55 ø 17' N, 131 ø 46'W). In a searchof the literature,and contacts with shorebirdspecialists in Asiaand the Pacific,we foundno evidenceof the prior occurrenceof thisspecies in the Pacific basin. Pistondiscovered the bird on 13 January2001 and watchedit for approximately one houras it fed on a rockygravel-covered beach with a flockof 35 BlackTurnstones (Arenaria rnelanocephala),three Rock Sandpipers(Calidris ptilocnernis),and two Surfbirds(Aph riza virgata).