The Social Organization of the Tlingit and Its Integration Into Daily Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tongass National Forest Roadless Rule Complaint

Katharine S. Glover (Alaska Bar No. 0606033) Eric P. Jorgensen (Alaska Bar No. 8904010) EARTHJUSTICE 325 Fourth Street Juneau, AK 99801 907.586.2751; [email protected]; [email protected] Nathaniel S.W. Lawrence (Wash. Bar No. 30847) (pro hac vice pending) NATURAL RESOURCES DEFENSE COUNCIL 3723 Holiday Drive, SE Olympia, WA 98501 360.534.9900; [email protected] Garett R. Rose (D.C. Bar No. 1023909) (pro hac vice pending) NATURAL RESOURCES DEFENSE COUNCIL 1152 15th St. NW Washington DC 20005 202.289.6868; [email protected] Attorneys for Plaintiffs Organized Village of Kake, et al. IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF ALASKA ORGANIZED VILLAGE OF KAKE; ORGANIZED VILLAGE OF ) SAXMAN; HOONAH INDIAN ASSOCIATION; KETCHIKAN ) INDIAN COMMUNITY; KLAWOCK COOPERATIVE ) ASSOCIATION; WOMEN’S EARTH AND CLIMATE ACTION ) Case No. 1:20-cv- NETWORK; THE BOAT COMPANY; UNCRUISE; ALASKA ) ________ LONGLINE FISHERMEN’S ASSOCIATION; SOUTHEAST ) ALASKA CONSERVATION COUNCIL; NATURAL RESOURCES ) DEFENSE COUNCIL; ALASKA RAINFOREST DEFENDERS; ) ALASKA WILDERNESS LEAGUE; SIERRA CLUB; DEFENDERS ) OF WILDLIFE; NATIONAL AUDUBON SOCIETY; CENTER FOR ) BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY; FRIENDS OF THE EARTH; THE ) WILDERNESS SOCIETY; GREENPEACE, INC.; NATIONAL ) WILDLIFE FEDERATION; and ENVIRONMENT AMERICA, ) ) Plaintiffs, ) v. ) ) SONNY PERDUE, in his official capacity as Secretary of ) Agriculture, UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF ) AGRICULTURE, STEPHEN CENSKY, or his successor, in his ) official capacity as Deputy Secretary of Agriculture; and UNITED ) STATES FOREST SERVICE, ) ) Defendants. ) COMPLAINT FOR DECLARATORY AND INJUNCTIVE RELIEF (5 U.S.C. §§ 701-706; 16 U.S.C. § 551; 16 U.S.C. § 1608; 42 U.S.C. § 4332; 16 U.S.C. § 3120) INTRODUCTION 1. This action challenges a rule, 36 C.F.R. -

Social Organization and Educational Change: a Case Study

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 095 064 SO 007 696 AUTHOR Wolcott, Harry F. TITLE Social Organization and 'educational Change: A Case Study. INSTITUTION Oregon Univ., Eugene. Center for Educational Policy Management. PUB DATE Mar 74 NOTE 13p.; Paper presented at the American Educational Research Association Symposium on "Anthropological Perspectives in Educational Evaluation" (Chicago, Illinois, April 17, 1974) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$1.50 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Administrator Role; Anthropology; Case Studies; *Educational Anthropology; *Educational Change; *Ethnology; Power Structure; *School Systems; *Social Organizations; Social Structure; Sociocultural Patterns; Teacher Role IDENTIFIERS *Moiety ABSTRACT Efforts to analyze a case study of the implementation of Program Planning Budgeting System (PPBS) materials for a pilot study in a school district are discussed from a descriptive, ethnographic approach. Antagonism, anxiety, and accusations characterize the extreme we-they split among those interviewed. Anthropology describes such a society with two major divisions as a moiety, one of two mutually exclusive divisions of a group. The educator community studied exhibits the characteristics of a moiety form of social organization in its two divisions of teachers and technocrats, and their two totems, students and reports respectively. The moiety perspective challenges the hierarchical bureaucratic model of school organization by showing a reasonable distribution of power between moieties. Educator moieties exhibit reciprocal behaviors, such that each division is dependent on the other and cannot maintain a viable educational subculture alone. The traditional subdivision of moieties into phratries and/or clans extends the scope of the analogy, explaining, for example, most teachers seem to find more in common with teachers of the same levels as themselves. -

Gender, Ritual and Social Formation in West Papua

Gender, ritual Pouwer Jan and social formation Gender, ritual in West Papua and social formation A configurational analysis comparing Kamoro and Asmat Gender,in West Papua ritual and social Gender, ritual and social formation in West Papua in West ritual and social formation Gender, This study, based on a lifelong involvement with New Guinea, compares the formation in West Papua culture of the Kamoro (18,000 people) with that of their eastern neighbours, the Asmat (40,000), both living on the south coast of West Papua, Indonesia. The comparison, showing substantial differences as well as striking similarities, contributes to a deeper understanding of both cultures. Part I looks at Kamoro society and culture through the window of its ritual cycle, framed by gender. Part II widens the view, offering in a comparative fashion a more detailed analysis of the socio-political and cosmo-mythological setting of the Kamoro and the Asmat rituals. These are closely linked with their social formations: matrilineally oriented for the Kamoro, patrilineally for the Asmat. Next is a systematic comparison of the rituals. Kamoro culture revolves around cosmological connections, ritual and play, whereas the Asmat central focus is on warfare and headhunting. Because of this difference in cultural orientation, similar, even identical, ritual acts and myths differ in meaning. The comparison includes a cross-cultural, structural analysis of relevant myths. This publication is of interest to scholars and students in Oceanic studies and those drawn to the comparative study of cultures. Jan Pouwer (1924) started his career as a government anthropologist in West New Guinea in the 1950s and 1960s, with periods of intensive fieldwork, in particular among the Kamoro. -

Native People in a Pacific World

Native People in a Pacific World: The Native Alaskan Encounter and Exchange with Native People of the Pacific Coast Gabe Chang-Deutsch 2,471 words Junior Research Paper The Unangan and Alutiiq peoples of Alaska worked in the fur trade in the early 1800s in Alaska, California and Hawaii. Their activities make us rethink the history of Native people and exploration, encounter and exchange. Most historical accounts focus on Native encounters with European people, but Native people also explored and met new Indigenous cultures. The early 1800s was a time of great global voyages and intermixing, from Captain Cook's Pacific voyages to the commercial fur trade in the eastern U.S to diverse workplaces in Atlantic world ports. The encounters and exchanges between and among Native people of the Pacific Coast are major part of this story. Relations between Native Alaskans, Native Californians and Hawaiians show how Native-to-Native encounters and exchanges were important in the creation of empire and the global economy. During the exploration of the Pacific coast in the early 1800s, Unangan and Alutiiq people created their own multicultural encounters and exchanges in the Pacific with Russian colonists, but most importantly with the indigenous people of Hawaii and California. By examining the religious and cultural exchanges with Russian fur traders in the Aleutian Islands, the creation of cosmopolitan domestic partnerships between different Native groups at Fort Ross and Native-to-Native artistic exchanges in Hawaii, we can see how Native-led events and ideas were integral to the growing importance of the Pacific and beginning an intercontinentally connected world. -

Tongass National Forest from the 2001 Roadless Area

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 10/29/2020 and available online at federalregister.gov/d/2020-23984, and on govinfo.gov [3411-15-P] DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Forest Service 36 CFR Part 294 RIN 0596-AD37 Special Areas; Roadless Area Conservation; National Forest System Lands in Alaska AGENCY: Forest Service, Agriculture Department (USDA). ACTION: Final rule and record of decision. SUMMARY: The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA or Department), is adopting a final rule to exempt the Tongass National Forest from the 2001 Roadless Area Conservation Rule (2001 Roadless Rule), which prohibits timber harvest and road construction/reconstruction with limited exceptions within designated inventoried roadless areas. In addition, the rule directs an administrative change to the timber suitability of lands deemed unsuitable, solely due to the application of the 2001 Roadless Rule, in the 2016 Tongass National Forest Land and Resource Management Plan (Tongass Forest Plan or Forest Plan), Appendix A. The rule does not authorize any ground-disturbing activities, nor does it increase the overall amount of timber harvested from the Tongass National Forest. DATES: This rule is effective [INSERT DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER]. FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Ken Tu, Interdisciplinary Team Leader, at 303-275-5156 or [email protected]. Individuals using telecommunication devices for the deaf (TDD) may call the Federal Information Relay Services at 1-800-877-8339 between 8 a.m. and 8 p.m. Eastern Time, Monday through Friday. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: The USDA Forest Service manages approximately 21.9 million acres of federal lands in Alaska, which are distributed across two national forests (Tongass and Chugach National Forests). -

Northwest Coast Archaeology

ANTH 442/542 - Northwest Coast Archaeology COURSE DESCRIPTION This course examines the more than 12,000 year old archaeological record of the Northwest Coast of North America, the culture area extending from southeast Alaska to coastal British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and northern California. This region has fascinated anthropologists for almost 150 years because its indigenous peoples have developed distinctive cultures based on fishing, hunting, and gathering economies. We begin by establishing the ecological and ethnographic background for the region, and then study how these have shaped archaeologists' ideas about the past. We study the contents of sites and consider the relationship between data, interpretation, and theory. Throughout the term, we discuss the dynamics of contact and colonialism and how these have impacted understandings of the recent and more distant pasts of these societies. This course will prepare you to understand and evaluate Northwest Coast archaeological news within the context of different jurisdictions. You will also have the opportunity to visit some archaeological sites on the Oregon coast. I hope the course will prepare you for a lifetime of appreciating Northwest Coast archaeology. WHERE AND WHEN Class: 10-11:50 am, Monday & Wednesday in Room 204 Condon Hall. Instructor: Dr. Moss Office hours: after class until 12:30 pm, and on Friday, 1:30-3:00 pm or by appointment 327 Condon, 346-6076; [email protected] REQUIRED READING: Moss, Madonna L. 2011 Northwest Coast: Archaeology as Deep History. SAA Press, Washington, D.C. All journal articles/book chapters in the “Course Readings” Module on Canvas. Please note that all royalties from the sale of this book go to the Native American Scholarship Fund of the Society for American Archaeology. -

Alaska Native

To conduct a simple search of the many GENERAL records of Alaska’ Native People in the National Archives Online Catalog use the search term Alaska Native. To search specific areas or villages see indexes and information below. Alaska Native Villages by Name A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Alaska is home to 229 federally recognized Alaska Native Villages located across a wide geographic area, whose records are as diverse as the people themselves. Customs, culture, artwork, and native language often differ dramatically from one community to another. Some are nestled within large communities while others are small and remote. Some are urbanized while others practice subsistence living. Still, there are fundamental relationships that have endured for thousands of years. One approach to understanding links between Alaska Native communities is to group them by language. This helps the student or researcher to locate related communities in a way not possible by other means. It also helps to define geographic areas in the huge expanse that is Alaska. For a map of Alaska Native language areas, see the generalized map of Alaska Native Language Areas produced by the University of Alaska at Fairbanks. Click on a specific language below to see Alaska federally recognized communities identified with each language. Alaska Native Language Groups (click to access associated Alaska Native Villages) Athabascan Eyak Tlingit Aleut Eskimo Haida Tsimshian Communities Ahtna Inupiaq with Mixed Deg Hit’an Nanamiut Language Dena’ina (Tanaina) -

Policy Recommendations for Tlingit Language Revitalization Efforts

Indigenous Tongues: Policy Recommendations for Tlingit Language Revitalization Efforts A Policy Paper for the National Indian Health Board Authored by: Keixe Yaxti/Maka Monture Of the Yakutat Tlingit Tribe of Alaska & Six Nations Mohawk of Canada Image 1: “Dig your paddle Deep” by Maka Monture Contents Introduction 2 Background on Tlingit Language 2 Health in Indigenous Languages 2 How Language Efforts Can be Developed 3 Where The State is Now 3 Closing Statement 4 References 4 Appendix I: Supporting Document: Tlingit Human Diagram 5 Appendix II: Supporting Document: Yakutat Tlingit Tribe Resolution 6 Appendix III: Supporting Document: House Concurrent Resolution 19 8 1 Introduction There is a dire need for native language education for the preservation of the Southeastern Alaskan Tlingit language, and Alaskan Tlingit Tribes must prioritize language restoration as the a priority of the tribe for the purpose of revitalizing and perpetuating the aboriginal language of their ancestors. According to the Alaska Native Language Preservation and Advisory Council, not only are a majority of the 20 recognized Alaska Native languages in danger of being lost at the end of this century, direct action is needed at tribal levels in Alaska. The following policy paper states why Alaskan Tlingit Tribes and The Central Council of the Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska, a tribal government representing over 30,000 Tlingit and Haida Indians worldwide and a sovereign entity that has a government to government relationship with the United States, must take actions to declare a state of emergency for the Tlingit Language and allocate resources for saving the Tlingit language through education programs. -

Interpreting the Tongass National Forest

INTERPRETING THE TONGASS NATIONAL FOREST via the ALASKA MARINE HIGHWAY U. S. Department of Agriculture Alaska Region Forest Service INTERPRETING THE TONGASS NATIONAL FOREST By D. R. (Bob) Hakala Visitor Information Service Illustrations by Ann Pritchard Surveys and Maps U.S.D.A. Forest Service Juneau, Alaska TO OUR VISITORS The messages in this booklet have been heard by thousands of travelers to Southeast Alaska. They were prepared originally as tape recordings to be broadcast by means of message repeater systems on board the Alaska State ferries and commercial cruise vessels plying the Alaska waters of the Inside Passage. Public interest caused us to publish them in this form so they would be available to anyone on ships traveling through the Tongass country. The U.S.D.A. Forest Service, in cooperation with the State of Alaska, has developed the interpretive program for the Alaska Marine Highway (Inside Passage) because, as one of the messages says, "... most of the landward view is National Forest. The Forest Service and the State of Alaska share the objective of providing factual, meaning ful information which adds understanding and pride in Alaska and the National Forests within its boundaries." We hope these pages will enrich your recall of Alaska scenes and adventures. Charles Yates Regional Forester 1 CONTENTS 1. THE PASSAGE AHEAD 3 2. WELCOME-. 4 1. THE PASSAGE AHEAD 3. ALASKA DISCOVERY 5 4. INTERNATIONAL BOUNDARY 6 5. TONGASS ISLAND 8 6. INDIANS OF SOUTHEAST ALASKA 10 Every place you travel is rich with history, nature lore, cul 7. CLIMATE 12 ture — the grand story of man and earth. -

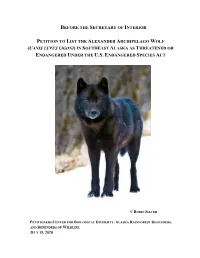

Petition to List the Alexander Archipelago Wolf in Southeast

BEFORE THE SECRETARY OF INTERIOR PETITION TO LIST THE ALEXANDER ARCHIPELAGO WOLF (CANIS LUPUS LIGONI) IN SOUTHEAST ALASKA AS THREATENED OR ENDANGERED UNDER THE U.S. ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT © ROBIN SILVER PETITIONERS CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY, ALASKA RAINFOREST DEFENDERS, AND DEFENDERS OF WILDLIFE JULY 15, 2020 NOTICE OF PETITION David Bernhardt, Secretary U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Margaret Everson, Principal Deputy Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Gary Frazer, Assistant Director for Endangered Species U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1840 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Greg Siekaniec, Alaska Regional Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1011 East Tudor Road Anchorage, AK 99503 [email protected] PETITIONERS Shaye Wolf, Ph.D. Larry Edwards Center for Biological Diversity Alaska Rainforest Defenders 1212 Broadway P.O. Box 6064 Oakland, California 94612 Sitka, Alaska 99835 (415) 385-5746 (907) 772-4403 [email protected] [email protected] Randi Spivak Patrick Lavin, J.D. Public Lands Program Director Defenders of Wildlife Center for Biological Diversity 441 W. 5th Avenue, Suite 302 (310) 779-4894 Anchorage, AK 99501 [email protected] (907) 276-9410 [email protected] _________________________ Date this 15 day of July 2020 2 Pursuant to Section 4(b) of the Endangered Species Act (“ESA”), 16 U.S.C. §1533(b), Section 553(3) of the Administrative Procedures Act, 5 U.S.C. § 553(e), and 50 C.F.R. § 424.14(a), the Center for Biological Diversity, Alaska Rainforest Defenders, and Defenders of Wildlife petition the Secretary of the Interior, through the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (“USFWS”), to list the Alexander Archipelago wolf (Canis lupus ligoni) in Southeast Alaska as a threatened or endangered species. -

Alaska Region New Employee Orientation Front Cover Shows Employees Working in Various Ways Around the Region

Forest Service UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Alaska Region | September 2021 Alaska Region New Employee Orientation Front cover shows employees working in various ways around the region. Alaska Region New Employee Orientation R10-UN-017 September 2021 Juneau’s typically temperate, wet weather is influenced by the Japanese Current and results in about 300 days a year with rain or moisture. Average rainfall is 92 inches in the downtown area and 54 inches ten miles away at the airport. Summer temperatures range between 45 °F and 65 °F (7 °C and 18 °C), and in the winter between 25 °F and 35 °F (-4 °C and -2 °C). On average, the driest months of the year are April and May and the wettest is October, with the warmest being July and the coldest January and February. Table of Contents National Forest System Overview ............................................i Regional Office .................................................................. 26 Regional Forester’s Welcome ..................................................1 Regional Leadership Team ........................................... 26 Alaska Region Organization ....................................................2 Acquisitions Management ............................................ 26 Regional Leadership Team (RLT) ............................................3 Civil Rights ................................................................... 26 Common Place Names .............................................................4 Ecosystems Planning and Budget ................................ -

Development of a Macroinvertebrate Biological Assessment Index for Alexander Archipelago Streams – Final Report

Development of a Macroinvertebrate Biological Assessment Index for Alexander Archipelago Streams – Final Report by Daniel J. Rinella, Daniel L. Bogan, and Keiko Kishaba Environment and Natural Resources Institute University of Alaska Anchorage 707 A Street, Anchorage, AK 99501 and Benjamin Jessup Tetra Tech, Inc. 400 Red Rock Boulevard, Suite 200 Owings Mills, MD 21117 for Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation Division of Air & Water Quality 555 Cordova Street, Anchorage, AK 99501 2005 1 Acknowledgments The authors extend their gratitude to the federal, state, and local governments; agencies; tribes; volunteer professional biologists; watershed groups; and private citizens that have supported this project. We thank Kim Hastings of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for coordinating lodging and transportation in Juneau and for use of the research vessels Curlew and Surf Bird. We thank Neil Stichert, Joe McClung, and Deb Rudis, also of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, for field assistance. We thank the U.S. Forest Service for lodging and transportation across the Tongass National Forest; specifically, we thank Julianne Thompson, Emil Tucker, Ann Puffer, Tom Cady, Aaron Prussian, Jim Beard, Steve Paustian, Brandy Prefontaine, and Sue Farzan for coordinating support and for field assistance and Liz Cabrera for support with the Southeast Alaska GIS Library. We thank Jack Gustafson of the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Cathy Needham of the Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska and POWTEC, John Hudson of the USFS Forestry Science Lab, Mike Crotteau of the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation, and Bruce Johnson of the Alaska Department of Natural Resources for help with field data collection, logistics and local expertise.