Identity, History and the Athabaskan Potlatch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tongass National Forest Roadless Rule Complaint

Katharine S. Glover (Alaska Bar No. 0606033) Eric P. Jorgensen (Alaska Bar No. 8904010) EARTHJUSTICE 325 Fourth Street Juneau, AK 99801 907.586.2751; [email protected]; [email protected] Nathaniel S.W. Lawrence (Wash. Bar No. 30847) (pro hac vice pending) NATURAL RESOURCES DEFENSE COUNCIL 3723 Holiday Drive, SE Olympia, WA 98501 360.534.9900; [email protected] Garett R. Rose (D.C. Bar No. 1023909) (pro hac vice pending) NATURAL RESOURCES DEFENSE COUNCIL 1152 15th St. NW Washington DC 20005 202.289.6868; [email protected] Attorneys for Plaintiffs Organized Village of Kake, et al. IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF ALASKA ORGANIZED VILLAGE OF KAKE; ORGANIZED VILLAGE OF ) SAXMAN; HOONAH INDIAN ASSOCIATION; KETCHIKAN ) INDIAN COMMUNITY; KLAWOCK COOPERATIVE ) ASSOCIATION; WOMEN’S EARTH AND CLIMATE ACTION ) Case No. 1:20-cv- NETWORK; THE BOAT COMPANY; UNCRUISE; ALASKA ) ________ LONGLINE FISHERMEN’S ASSOCIATION; SOUTHEAST ) ALASKA CONSERVATION COUNCIL; NATURAL RESOURCES ) DEFENSE COUNCIL; ALASKA RAINFOREST DEFENDERS; ) ALASKA WILDERNESS LEAGUE; SIERRA CLUB; DEFENDERS ) OF WILDLIFE; NATIONAL AUDUBON SOCIETY; CENTER FOR ) BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY; FRIENDS OF THE EARTH; THE ) WILDERNESS SOCIETY; GREENPEACE, INC.; NATIONAL ) WILDLIFE FEDERATION; and ENVIRONMENT AMERICA, ) ) Plaintiffs, ) v. ) ) SONNY PERDUE, in his official capacity as Secretary of ) Agriculture, UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF ) AGRICULTURE, STEPHEN CENSKY, or his successor, in his ) official capacity as Deputy Secretary of Agriculture; and UNITED ) STATES FOREST SERVICE, ) ) Defendants. ) COMPLAINT FOR DECLARATORY AND INJUNCTIVE RELIEF (5 U.S.C. §§ 701-706; 16 U.S.C. § 551; 16 U.S.C. § 1608; 42 U.S.C. § 4332; 16 U.S.C. § 3120) INTRODUCTION 1. This action challenges a rule, 36 C.F.R. -

Big Delta Quadrangle Delta Big 1:250,000 - 3645

Big Delta quadrangle Descriptions of the mineral occurrences shown on the accompanying figure follow. See U.S. Geological Survey (1996) for a description of the information content of each field in the records. The data presented here are maintained as part of a statewide database on mines, prospects and mineral occurrences throughout Alaska. o o o o o o o o Distribution of mineral occurrences in the Big Delta 1:250,000-scale quadrangle, Alaska This and related reports are accessible through the USGS World Wide Web site http://ardf.wr.usgs.gov. Comments or information regarding corrections or missing data, or requests for digital retrievals should be directed to Donald Grybeck, USGS, 4200 Unversity Dr., Anchorage, AK 99508-4667, email [email protected], telephone (907) 786-7424. This compilation is authored by: Cameron Rombach Alaska Division of Geological & Geophysical Surveys 794 University Ave., Suite 200 Fairbanks, AK 99709-3645 Alaska Resource Data File This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geologi- cal Survey editorial standards or with the North American Stratigraphic code. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. OPEN-FILE REPORT 99-354 Alaska Resource Data File BD001 Site name(s): Banner Creek Site type: Mines ARDF no.: BD001 Latitude: 64.316 Quadrangle: BD B-5 Longitude: 146.346 Location description and accuracy: Banner Creek drains southward into the Tanana River. The approximate center of min- ing activity on Banner Creek is in SW1/4SW1/4 section 10, T. -

Native People in a Pacific World

Native People in a Pacific World: The Native Alaskan Encounter and Exchange with Native People of the Pacific Coast Gabe Chang-Deutsch 2,471 words Junior Research Paper The Unangan and Alutiiq peoples of Alaska worked in the fur trade in the early 1800s in Alaska, California and Hawaii. Their activities make us rethink the history of Native people and exploration, encounter and exchange. Most historical accounts focus on Native encounters with European people, but Native people also explored and met new Indigenous cultures. The early 1800s was a time of great global voyages and intermixing, from Captain Cook's Pacific voyages to the commercial fur trade in the eastern U.S to diverse workplaces in Atlantic world ports. The encounters and exchanges between and among Native people of the Pacific Coast are major part of this story. Relations between Native Alaskans, Native Californians and Hawaiians show how Native-to-Native encounters and exchanges were important in the creation of empire and the global economy. During the exploration of the Pacific coast in the early 1800s, Unangan and Alutiiq people created their own multicultural encounters and exchanges in the Pacific with Russian colonists, but most importantly with the indigenous people of Hawaii and California. By examining the religious and cultural exchanges with Russian fur traders in the Aleutian Islands, the creation of cosmopolitan domestic partnerships between different Native groups at Fort Ross and Native-to-Native artistic exchanges in Hawaii, we can see how Native-led events and ideas were integral to the growing importance of the Pacific and beginning an intercontinentally connected world. -

Tongass National Forest from the 2001 Roadless Area

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 10/29/2020 and available online at federalregister.gov/d/2020-23984, and on govinfo.gov [3411-15-P] DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Forest Service 36 CFR Part 294 RIN 0596-AD37 Special Areas; Roadless Area Conservation; National Forest System Lands in Alaska AGENCY: Forest Service, Agriculture Department (USDA). ACTION: Final rule and record of decision. SUMMARY: The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA or Department), is adopting a final rule to exempt the Tongass National Forest from the 2001 Roadless Area Conservation Rule (2001 Roadless Rule), which prohibits timber harvest and road construction/reconstruction with limited exceptions within designated inventoried roadless areas. In addition, the rule directs an administrative change to the timber suitability of lands deemed unsuitable, solely due to the application of the 2001 Roadless Rule, in the 2016 Tongass National Forest Land and Resource Management Plan (Tongass Forest Plan or Forest Plan), Appendix A. The rule does not authorize any ground-disturbing activities, nor does it increase the overall amount of timber harvested from the Tongass National Forest. DATES: This rule is effective [INSERT DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER]. FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Ken Tu, Interdisciplinary Team Leader, at 303-275-5156 or [email protected]. Individuals using telecommunication devices for the deaf (TDD) may call the Federal Information Relay Services at 1-800-877-8339 between 8 a.m. and 8 p.m. Eastern Time, Monday through Friday. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: The USDA Forest Service manages approximately 21.9 million acres of federal lands in Alaska, which are distributed across two national forests (Tongass and Chugach National Forests). -

Alaska Native

To conduct a simple search of the many GENERAL records of Alaska’ Native People in the National Archives Online Catalog use the search term Alaska Native. To search specific areas or villages see indexes and information below. Alaska Native Villages by Name A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Alaska is home to 229 federally recognized Alaska Native Villages located across a wide geographic area, whose records are as diverse as the people themselves. Customs, culture, artwork, and native language often differ dramatically from one community to another. Some are nestled within large communities while others are small and remote. Some are urbanized while others practice subsistence living. Still, there are fundamental relationships that have endured for thousands of years. One approach to understanding links between Alaska Native communities is to group them by language. This helps the student or researcher to locate related communities in a way not possible by other means. It also helps to define geographic areas in the huge expanse that is Alaska. For a map of Alaska Native language areas, see the generalized map of Alaska Native Language Areas produced by the University of Alaska at Fairbanks. Click on a specific language below to see Alaska federally recognized communities identified with each language. Alaska Native Language Groups (click to access associated Alaska Native Villages) Athabascan Eyak Tlingit Aleut Eskimo Haida Tsimshian Communities Ahtna Inupiaq with Mixed Deg Hit’an Nanamiut Language Dena’ina (Tanaina) -

Policy Recommendations for Tlingit Language Revitalization Efforts

Indigenous Tongues: Policy Recommendations for Tlingit Language Revitalization Efforts A Policy Paper for the National Indian Health Board Authored by: Keixe Yaxti/Maka Monture Of the Yakutat Tlingit Tribe of Alaska & Six Nations Mohawk of Canada Image 1: “Dig your paddle Deep” by Maka Monture Contents Introduction 2 Background on Tlingit Language 2 Health in Indigenous Languages 2 How Language Efforts Can be Developed 3 Where The State is Now 3 Closing Statement 4 References 4 Appendix I: Supporting Document: Tlingit Human Diagram 5 Appendix II: Supporting Document: Yakutat Tlingit Tribe Resolution 6 Appendix III: Supporting Document: House Concurrent Resolution 19 8 1 Introduction There is a dire need for native language education for the preservation of the Southeastern Alaskan Tlingit language, and Alaskan Tlingit Tribes must prioritize language restoration as the a priority of the tribe for the purpose of revitalizing and perpetuating the aboriginal language of their ancestors. According to the Alaska Native Language Preservation and Advisory Council, not only are a majority of the 20 recognized Alaska Native languages in danger of being lost at the end of this century, direct action is needed at tribal levels in Alaska. The following policy paper states why Alaskan Tlingit Tribes and The Central Council of the Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska, a tribal government representing over 30,000 Tlingit and Haida Indians worldwide and a sovereign entity that has a government to government relationship with the United States, must take actions to declare a state of emergency for the Tlingit Language and allocate resources for saving the Tlingit language through education programs. -

Interpreting the Tongass National Forest

INTERPRETING THE TONGASS NATIONAL FOREST via the ALASKA MARINE HIGHWAY U. S. Department of Agriculture Alaska Region Forest Service INTERPRETING THE TONGASS NATIONAL FOREST By D. R. (Bob) Hakala Visitor Information Service Illustrations by Ann Pritchard Surveys and Maps U.S.D.A. Forest Service Juneau, Alaska TO OUR VISITORS The messages in this booklet have been heard by thousands of travelers to Southeast Alaska. They were prepared originally as tape recordings to be broadcast by means of message repeater systems on board the Alaska State ferries and commercial cruise vessels plying the Alaska waters of the Inside Passage. Public interest caused us to publish them in this form so they would be available to anyone on ships traveling through the Tongass country. The U.S.D.A. Forest Service, in cooperation with the State of Alaska, has developed the interpretive program for the Alaska Marine Highway (Inside Passage) because, as one of the messages says, "... most of the landward view is National Forest. The Forest Service and the State of Alaska share the objective of providing factual, meaning ful information which adds understanding and pride in Alaska and the National Forests within its boundaries." We hope these pages will enrich your recall of Alaska scenes and adventures. Charles Yates Regional Forester 1 CONTENTS 1. THE PASSAGE AHEAD 3 2. WELCOME-. 4 1. THE PASSAGE AHEAD 3. ALASKA DISCOVERY 5 4. INTERNATIONAL BOUNDARY 6 5. TONGASS ISLAND 8 6. INDIANS OF SOUTHEAST ALASKA 10 Every place you travel is rich with history, nature lore, cul 7. CLIMATE 12 ture — the grand story of man and earth. -

1. Description 1.1 Name of Society, Language, and Language Family: Ahtna, Na Dene, Athapaskan 1.2 ISO Code (3 Letter Code from E

1. Description 1.1 Name of society, language, and language family: Ahtna, Na Dene, Athapaskan 1.2 ISO code (3 letter code from ethnologue.com): ath 1.3 Location (latitude/longitude): 61.312452,-142.470703 1.4 Brief history: Russians first made contact with the Ahtna in 1783. They attempted to set up Copper fort, near Taral, in Ahtna territory, but the Ahtna were hostile towards them, massacring a group of explorers led by Ruff Serebrennikov in 1848, which led to the closing of the fort. When the fort was reopened for a short while, only a little trade between the Ahtna and the Russians occurred. Smallpox killed many Ahtna from 1837-1839. After the US purchased Alaska the Ahtna traded directly with the Alaska Commercial Company at Nuchek and indirectly with other posts in the Yukon. The first major encounter with whites happened at the beginning of the 20th century when word of gold in the area brought masses of people north. This introduced luxuries and tuberculosis to the Ahtna People. By 1930, all Ahtna had been baptized into the Russian Orthodox religion. (De Laguna, Frederica & McClellan, Catherine) 1.5 Influence of missionaries/schools/governments/powerful neighbors: Contact with whites led to epidemics that devastated the Ahtna population. By the mid- 20th century, all Ahtna had been converted or baptized into the Russian Orthodox faith. (De Laguna, Frederica & McClellan, Catherine) 1.6 Ecology The climate of the Copper River valley where the Ahtna lived is transitional between maritime and continental. Snow covered the inhabited area from mid-November through mid-April. -

Highlights YNLC Moved Into Summer Activities Following Yukon College Graduation and the Close of School Language Programs in June

YNLC ACTIVITIES REPO R T COVE R I N G THE PE R IOD JU ly – DE C EMBE R 2009 Highlights YNLC moved into summer activities following Yukon College graduation and the close of school language programs in June. In July, staff linguist Doug Hitch presented recent YNLC research on the Kohklux maps at the International Conference on the History of Cartography in Copenhagen, Denmark. In July and August, YNLC Director John Ritter attended meetings at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. YNLC's Linda Harvey and Mary Jane Allison attended the six-week summer session at UAF, continuing coursework toward academic degrees offered collaboratively with Yukon College and YNLC. Two Alaskan visitors from the Upper Kuskokwim region came to YNLC in August for technical training for web-based language projects. With the start of school programs in the fall, the Centre also resumed its training schedule which continued to the Christmas break. Eleven instructors from three Yukon language groups participated in the September Native Language Certificate/Diploma training session spearheaded by YNLC coordinators Linda Harvey and Jo-Anne Johnson. In late November, YNLC held one of its largest-ever Tukudh (Gwich’in) literacy sessions, with thirty-one participants from Yukon, NWT, and Alaska. Successful Tlingit and Hän literacy sessions were also held this fall. Cooperative work with the Yukon Geographical Place Names Board continued in the fall and included a place-name survey of the Kusawa Lake and Mendenhall River area. Looking north at Na/khu\ç, traditional rafting-across point on Kusawa Lake. The Southern Tutchone name for the lake, Na/khu\ç MaÜn, comes from this feature. -

Seasonal Habitats of Arctic Grayling in the Upper Goodpaster River Gold Mining District

Regional Operational Plan SF.3F.2014.06 Operational Plan: Seasonal Habitats of Arctic Grayling in the Upper Goodpaster River Gold Mining District by Andrew D. Gryska March 2015 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Divisions of Sport Fish and Commercial Fisheries Symbols and Abbreviations The following symbols and abbreviations, and others approved for the Système International d'Unités (SI), are used without definition in the following reports by the Divisions of Sport Fish and of Commercial Fisheries: Fishery Manuscripts, Fishery Data Series Reports, Fishery Management Reports, and Special Publications. All others, including deviations from definitions listed below, are noted in the text at first mention, as well as in the titles or footnotes of tables, and in figure or figure captions. Weights and measures (metric) General Mathematics, statistics centimeter cm Alaska Administrative all standard mathematical deciliter dL Code AAC signs, symbols and gram g all commonly accepted abbreviations hectare ha abbreviations e.g., Mr., Mrs., alternate hypothesis HA kilogram kg AM, PM, etc. base of natural logarithm e kilometer km all commonly accepted catch per unit effort CPUE liter L professional titles e.g., Dr., Ph.D., coefficient of variation CV meter m R.N., etc. common test statistics (F, t, χ2, etc.) milliliter mL at @ confidence interval CI millimeter mm compass directions: correlation coefficient east E (multiple) R Weights and measures (English) north N correlation coefficient cubic feet per second ft3/s south S (simple) r foot ft west W covariance cov gallon gal copyright degree (angular ) ° inch in corporate suffixes: degrees of freedom df mile mi Company Co. -

CURRICULUM VITAE for JAMES KARI September, 2018

1 CURRICULUM VITAE FOR JAMES KARI September, 2018 BIOGRAPHICAL James M. Kari Business address: Dena=inaq= Titaztunt 1089 Bruhn Rd. Fairbanks, AK 99709 E-mail: [email protected] Federal DUNS number: 189991792, Alaska Business License No. 982354 EDUCATION Ph.D., University of New Mexico (Curriculum & Instruction and Linguistics), 1973 Doctoral dissertation: Navajo Verb Prefix Phonology (diss. advisors: Stanley Newman, Bruce Rigsby, Robert Young, Ken Hale; 1976 Garland Press book, regularly used as text on Navajo linguistics at several universities) M.A.T., Reed College (Teaching English), 1969 U. S. Peace Corps, Teacher of English as a Foreign Language, Bafra Lisesi, Bafra, Turkey, 1966-68 B.A., University of California at Los Angeles (English), 1966 Professional certification: general secondary teaching credential (English) in California and Oregon Languages: Field work: Navajo (1970), Dena'ina (1972), Ahtna (1973), Deg Hit=an (Ingalik) (1974), Holikachuk (1975), Babine-Witsu Wit'en (1975), Koyukon (1977), Lower Tanana (1980), Tanacross (1983), Upper Tanana (1985), Middle Tanana (1990) Speaking: Dena’ina, Ahtna, Lower Tanana; some Turkish EMPLOYMENT Research consultant on Dene languages and resource materials, business name Dena’inaq’ Titaztunt, 1997 Professor of Linguistics, Emeritus, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, 1997 Professor of Linguistics, Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, 1993-97 Associate Professor of Linguistics, Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska, 1982-1993 Assistant Professor -

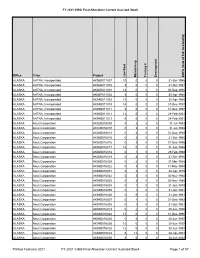

FY 2021 Final Summary

FY 2021 IHBG Final Allocation Current Assisted Stock Office Tribe Project Low RentLow Mutual Help Turnkey II Development (Date DOFA of Full Availability) ALASKA AHTNA, Incorporated AK06B011007 10 0 0 0 31-Oct-1986 ALASKA AHTNA, Incorporated AK06B011008 3 0 0 0 31-Oct-1987 ALASKA AHTNA, Incorporated AK06B011009 14 0 0 0 30-Sep-1990 ALASKA AHTNA, Incorporated AK06P011004 8 0 0 0 30-Apr-1980 ALASKA AHTNA, Incorporated AK94B011003 12 0 0 0 30-Apr-1980 ALASKA AHTNA, Incorporated AK94B011010 14 0 0 0 31-Dec-1997 ALASKA AHTNA, Incorporated AK94B011011 6 0 0 0 31-Dec-1997 ALASKA AHTNA, Incorporated AK94B011012 12 0 0 0 28-Feb-2001 ALASKA AHTNA, Incorporated AK94B011013 6 0 0 0 28-Feb-2001 ALASKA Aleut Corporation AK02B016009 0 2 0 0 31-Jul-1983 ALASKA Aleut Corporation AK02B016010 0 3 0 0 31-Jul-1986 ALASKA Aleut Corporation AK06B016012 0 4 0 0 31-Dec-1985 ALASKA Aleut Corporation AK06B016015 0 3 0 0 31-Oct-1985 ALASKA Aleut Corporation AK06B016016 0 3 0 0 31-Dec-1985 ALASKA Aleut Corporation AK06B016017 14 0 0 0 31-Jan-1986 ALASKA Aleut Corporation AK06B016018 0 1 0 0 29-Feb-1988 ALASKA Aleut Corporation AK06B016019 0 8 0 0 31-Oct-1990 ALASKA Aleut Corporation AK06B016020 0 2 0 0 31-Mar-1988 ALASKA Aleut Corporation AK06B016022 0 3 0 0 31-May-1994 ALASKA Aleut Corporation AK94B016001 0 2 0 0 30-Apr-1979 ALASKA Aleut Corporation AK94B016002 0 3 0 0 30-Nov-1980 ALASKA Aleut Corporation AK94B016003 0 2 0 0 30-Nov-1980 ALASKA Aleut Corporation AK94B016004 0 1 0 0 31-Jan-1979 ALASKA Aleut Corporation AK94B016005 0 1 0 0 31-Oct-1981 ALASKA Aleut Corporation