Documentation, Object Recording, and the Role of Curators in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

W534 Bird Coffin. by Amber Furmage

1 Life Cycle of an Object W534 – Bird Coffin Introduction W534, a bird coffin, currently resides in the animal case of the House of Death, The Egypt Centre, Swansea. The coffin came to Swansea in 1971, having been donated by the Wellcome Trustees. The Egypt Centre have dated it from between the Late Dynastic to the Graeco-Roman Period.1 It was constructed from a yellowish wood of poor quality with a coarse grain. Description Dimensions The bird coffin measures 436mm length by 139mm width at its largest point. The ventral cavity2 measures 330mm length by 68mm width, reaching a depth of 67mm from where the panel would be fitted. The head is 104mm height, making up 23.85% of the entire body. The beak then measures 22mm, 21.15% of the size of the head. The holes in the legs are of uneven proportions, both being 17mm in length but the right hole being 16mm width compared to the 12mm width of the left hole.3 Table 1 – Dimensions of W534 – Measurements taken by Author Feature Length Width Width Height Depth (largest) (smallest) Body 436mm 139mm Tail 104mm Head 80mm 104mm Beak 27mm 22mm Left leg hole 17mm 12mm Right leg hole 17mm 16mm Ventral cavity 330mm 68mm 39mm 67mm 1 The Egypt Centre, 2005. 2 See Figure 1. 3 See Figure 2 and Figure 3. Amber Furmage 2 Brief Description The piece is a yellowish wood4 carved to into a zoomorphic shape and coated in paint. The paint varies between features, some being black and other sections being red.5 The lack of paint on the top of the head6 may simply be an abrasion, however, due to the circular nature of the deficient, is perhaps more likely to be an area that had been covered up prior to painting and is now missing this element. -

I General for Place Names See Also Maps and Their Keys

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-12098-2 - Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology Edited by Paul T. Nicholson and Ian Shaw Index More information Index I General For place names see also maps and their keys. AAS see atomic absorption specrophotometry Tomb E21 52 aerenchyma 229 Abbad region 161 Tomb W2 315 Aeschynomene elaphroxylon 336 Abdel ‘AI, 1. 51 Tomb 113 A’09 332 Afghanistan 39, 435, 436, 443 abesh 591 Umm el-Qa’ab, 63, 79, 363, 496, 577, 582, African black wood 338–9, 339 Abies 445 591, 594, 631, 637 African iron wood 338–9, 339 A. cilicica 348, 431–2, 443, 447 Tomb Q 62 agate 15, 21, 25, 26, 27 A. cilicica cilicica 431 Tomb U-j 582 Agatharchides 162 A. cilicica isaurica 431 Cemetery U 79 agathic acid 453 A. nordmanniana 431 Abyssinia 46 Agathis 453, 464 abietane 445, 454 acacia 91, 148, 305, 335–6, 335, 344, 367, 487, Agricultural Museum, Dokki (Cairo) 558, 559, abietic acid 445, 450, 453 489 564, 632, 634, 666 abrasive 329, 356 Acacia 335, 476–7, 488, 491, 586 agriculture 228, 247, 341, 344, 391, 505, Abrak 148 A. albida 335, 477 506, 510, 515, 517, 521, 526, 528, 569, Abri-Delgo Reach 323 A. arabica 477 583, 584, 609, 615, 616, 617, 628, 637, absorption spectrophotometry 500 A. arabica var. adansoniana 477 647, 656 Abu (Elephantine) 323 A. farnesiana 477 agrimi 327 Abu Aggag formation 54, 55 A. nilotica 279, 335, 354, 367, 477, 488 A Group 323 Abu Ghalib 541 A. nilotica leiocarpa 477 Ahmose (Amarna oªcial) 115 Abu Gurob 410 A. -

Who's Who in Ancient Egypt

Who’s Who IN ANCIENT EGYPT Available from Routledge worldwide: Who’s Who in Ancient Egypt Michael Rice Who’s Who in the Ancient Near East Gwendolyn Leick Who’s Who in Classical Mythology Michael Grant and John Hazel Who’s Who in World Politics Alan Palmer Who’s Who in Dickens Donald Hawes Who’s Who in Jewish History Joan Comay, new edition revised by Lavinia Cohn-Sherbok Who’s Who in Military History John Keegan and Andrew Wheatcroft Who’s Who in Nazi Germany Robert S.Wistrich Who’s Who in the New Testament Ronald Brownrigg Who’s Who in Non-Classical Mythology Egerton Sykes, new edition revised by Alan Kendall Who’s Who in the Old Testament Joan Comay Who’s Who in Russia since 1900 Martin McCauley Who’s Who in Shakespeare Peter Quennell and Hamish Johnson Who’s Who in World War Two Edited by John Keegan Who’s Who IN ANCIENT EGYPT Michael Rice 0 London and New York First published 1999 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2004. © 1999 Michael Rice The right of Michael Rice to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

119 Original Article the GOLDEN SHRINES of TUTANKHAMUN

id9070281 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com Egyptian Journal of Archaeological and Restoration Studies "EJARS" An International peer-reviewed journal published bi-annually Volume 2, Issue 2, December - 2012: pp: 119-130 www. ejars.sohag-univ.edu.eg Original article THE GOLDEN SHRINES OF TUTANKHAMUN AND THEIR INTENDED BURIAL PLACE Soliman, R. Lecturer, Tourism guidance dept., Faculty of Archaeology & Tourism guidance, Misr Univ. for Sciences & Technology, 6th October city, Egypt E-mail: [email protected] Received 3/5/2012 Accepted 12/10/2012 Abstract The most famous tomb at the Valley of the Kings, KV 62 housed so far the most intact discovery of royal funerary treasures belonging to the eighteenth dynasty boy-king Tutankhamun. The tomb has a simple architectural plan clearly prepared for a non- royal burial. However, the hastily death of Tutankhamun at a young age caused his interment in such unusually small tomb. The treasures discovered were immense in number, art finesse and especially in the amount of gold used. Of these treasures the largest shrine of four shrines laid in the burial chamber needed to be dismantled and reassembled in the tomb because of its immense size. Clearly the black marks on this shrine helped in the assembly and especially the orientation in relation to the burial chamber. These marks are totally incorrect and prove that Tutankhamun was definitely intended to be buried in another tomb. Keywords: KV62, WV23, Golden shrines, Tutankhamun, Burial chamber, Orientation. 1. Introduction Tutankhamun was only nine and the real cause of his death remains years old when he got to throne; at that enigmatic. -

Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun's Family

Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun's Family Zahi Hawass; Yehia Z. Gad; Somaia Ismail; et al. JAMA. 2010;303(7):638-647 (doi:10.1001/jama.2010.121) Online article and related content current as of October 14, 2010. http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/303/7/638 Supplementary material eSupplement http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/303/7/638/DC1 Correction Contact me if this article is corrected. Citations This article has been cited 7 times. Contact me when this article is cited. Topic collections Neurology; Neurogenetics; Movement Disorders; Rheumatology; Musculoskeletal Syndromes (Chronic Fatigue, Gulf War); Malaria; Genetics; Genetic Disorders; Humanities; History of Medicine; Infectious Diseases Contact me when new articles are published in these topic areas. Related Articles published in King Tutankhamun, Modern Medical Science, and the Expanding Boundaries of the same issue Historical Inquiry Howard Markel. JAMA. 2010;303(7):667. Related Letters King Tutankhamun’s Family and Demise Eline D. Lorenzen et al. JAMA. 2010;303(24):2471. Brenda J. Baker. JAMA. 2010;303(24):2471. James G. Gamble. JAMA. 2010;303(24):2472. Irwin M. Braverman et al. JAMA. 2010;303(24):2472. Christian Timmann et al. JAMA. 2010;303(24):2473. Subscribe Email Alerts http://jama.com/subscribe http://jamaarchives.com/alerts Permissions Reprints/E-prints [email protected] [email protected] http://pubs.ama-assn.org/misc/permissions.dtl Downloaded from www.jama.com by guest on October 14, 2010 ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun’s Family Zahi Hawass, PhD Context The New Kingdom in ancient Egypt, comprising the 18th, 19th, and 20th Yehia Z. -

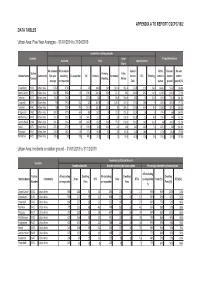

DSFRA IKEN Report Template

APPENDIX A TO REPORT CSCPC/19/2 DATA TABLES Urban Area: Five-Year Averages – 01/04/2014 to 31/04/2019 Incidents on station grounds Location False Pump Attendances Overview Fires Special Service Alarm All incidents All incidents Special All by On own On own Station Primary: False Station Name Community five-year excluding Co-responder All Primary Secondary Service RTC Flooding station's station station Number Dwelling Alarms average co-responder Calls pumps ground ground (%) Greenbank KV50 Urban Area 878.6 878.6 0 245 104.6 56.6 140.4 361.4 271.8 21.6 24.6 1424.8 974.2 68.4% Danes Castle KV32 Urban Area 832.6 830.8 1.8 198.8 126.4 56.6 72.4 385 248.4 29.2 14.8 1090.6 849.4 77.9% Torquay KV17 Urban Area 744.8 744.8 0 207.8 111 59 96.8 306.8 230 36 15.8 919.8 776.4 84.4% Crownhill KV49 Urban Area 742 741.8 0.2 227 100.6 43 126.4 337.4 177.4 28.6 9 878.4 680.6 77.5% Taunton KV61 Urban Area 734 733.4 0.6 227.8 132.8 56.6 95 284.6 221.6 65.4 8.4 1038.8 901.8 86.8% Bridgwater KV62 Urban Area 584.2 577.6 6.6 160 88.2 38 71.8 231.8 192.4 56 8 774.4 666 86.0% Middlemoor KV59 Urban Area 537.6 535.8 1.8 144.2 91.2 33 53 239.6 153.8 51 8.8 724.4 444 61.3% Camels Head KV48 Urban Area 491.6 491.2 0.4 162.8 85.2 50.4 77.6 178.6 150.2 16.6 11.8 638 390.2 61.2% Yeovil KV73 Urban Area 471.6 471.6 0 139.6 78.6 34.8 61 191 141 46.8 7.4 674.2 569 84.4% Plympton KV47 Urban Area 218.4 204.4 14 57.8 34.8 12 23 87.8 72.4 18.6 3 170.6 135.8 79.6% Plymstock KV51 Urban Area 185.8 185 0.8 48.4 27.4 12 21 76.8 60.6 12.6 2.6 165.4 123.8 74.8% Urban Area: Incidents on -

The Gazelle in Ancient Egyptian Art Image and Meaning

Uppsala Studies in Egyptology - 6 - Department of Archaeology and Ancient History Uppsala University For my parents Dorrit and Hindrik Åsa Strandberg The Gazelle in Ancient Egyptian Art Image and Meaning Uppsala 2009 Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in the Auditorium Minus of the Museum Gustavianum, Uppsala, Friday, October 2, 2009 at 09:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Abstract Strandberg, Åsa. 2009. The Gazelle in Ancient Egyptian Art. Image and Meaning. Uppsala Studies in Egyptology 6. 262 pages, 83 figures. Published by the Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, Uppsala University. xviii +262 pp. ISSN 1650-9838, ISBN 978-91-506-2091-7. This thesis establishes the basic images of the gazelle in ancient Egyptian art and their meaning. A chronological overview of the categories of material featuring gazelle images is presented as a background to an interpretation. An introduction and review of the characteristics of the gazelle in the wild are presented in Chapters 1-2. The images of gazelle in the Predynastic material are reviewed in Chapter 3, identifying the desert hunt as the main setting for gazelle imagery. Chapter 4 reviews the images of the gazelle in the desert hunt scenes from tombs and temples. The majority of the motifs characteristic for the gazelle are found in this context. Chapter 5 gives a typological analysis of the images of the gazelle from offering processions scenes. In this material the image of the nursing gazelle is given particular importance. Similar images are also found on objects, where symbolic connotations can be discerned (Chapter 6). -

June 17 Newsletter

ESSEX EGYPTOLOGY GROUP Newsletter 108 June/July 2017 DATES FOR YOUR DIARY 4th June Hatshepsut’s temple at Deir el-Bahri: Sergio Alarcon Robledo 2nd July The stone village at Amarna: Anna Garnett 6th August Short talks, book auction and annual general meeting 3rd September Justice in ancient Egypt: Alexandre Loktionov 1st October Ancient Egyptian Furniture: from the earliest to those “wonderful things” of the New Kingdom: Dr Geoffrey Killen This month we welcome, from Madrid, Sergio Alarcón Robledo. Sergio is one of the architects working at the Polish-Egyptian Archaeological and Conservation Mission of the Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari. He has studied Architecture at the Technical University of Madrid, and the MPhil of Egyptology at the University of Cambridge. His work has mainly focused on the excavation and interpretation of architectural evidence from ancient Egypt. His fieldwork experience includes his work at Deir el-Bahari and some nearby New Kingdom and Third Intermediate Period tombs. This coming season he will also join the Middle Kingdom Theban Project and the Egypt Exploration Society’s Mission at Zawyet Sultan. The temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari, is one of the oldest known New Kingdom royal buildings, and is key for the interpretation of the Theban mortuary temples, as well as for a better understanding of how the royal identity was shaped in the beginning of the New Kingdom. His talk will give an overview of the temple showing both its importance in the development of New Kingdom traditions and explaining the main archaeological and restoration works which have been carried out since 1855. -

Come My Staff, I Lean Upon You: an Iconographic and Contextual Study of Sticks and Staves from 18Th Dynasty Egypt

The American University in Cairo School of Humanities and Social Sciences Come My Staff, I Lean Upon You: an Iconographic and Contextual Study of Sticks and Staves from 18th Dynasty Egypt A Thesis Submitted to The Department of Sociology, Anthropology, Psychology and Egyptology (SAPE) In partial fulfillment of the requirements for The Degree of Master of Arts By: Nicholas R. Brown Under the Supervision of Dr. Salima Ikram First Reader: Dr. Lisa Sabbahy Second Reader: Dr. Fayza Haikal December, 2015 DEDICATION “All men dream, but not equally. Those who dream by night in the dusty recesses of their minds, wake in the day to find that it was vanity: but the dreamers of the day are dangerous men, for they may act on their dreams with open eyes, to make them possible. This I did.” -T. E. Lawrence, Seven Pillars of Wisdom To my grandmother, Nana Joan. For first showing me the “Wonderful Things” of ancient Egypt. I love you dearly. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are many individuals and institutions to whom I would like to express my deepest gratitude and thankfulness. Without their help, encouragement, support, and patience I would not have been able to complete my degree nor this thesis. Firstly, to my advisor Dr. Salima Ikram: I am grateful for your suggesting the idea of studying sticks in ancient Egypt, and for the many lessons that you have taught and opportunities you have provided for me throughout this entire process. I am, hopefully, a better scholar (and speller!) because of your investment in my research. Thank you. To my readers Doctors Lisa Sabbahy and Fayza Haikal, thank you for taking the time to review, comment upon, and edit my thesis draft. -

ABSTRACT Carl Nicholas Reeves STUDIES in the ARCHAEOLOGY

ABSTRACT Carl Nicholas Reeves STUDIES IN THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE VALLEY OF THE KINGS, with particular reference to tomb robbery and the caching of the royal mummies This study considers the physical evidence for tomb robbery on the Theban west bank, and its resultant effects, during the New Kingdom and Third Intermediate Period. Each tomb and deposit known from the Valley of the Kings is examined in detail, with the aims of establishing the archaeological context of each find and, wherever possible, isolating and comparing the evidence for post-interment activity. The archaeological and documentary evidence pertaining to the royal caches from Deir el-Bahri, the tomb of Amenophis II and elsewhere is drawn together, and from an analysis of this material it is possible to suggest the routes by which the mummies arrived at their final destinations. Large-scale tomb robbery is shown to have been a relatively uncommon phenomenon, confined to periods of political and economic instability. The caching of the royal mummies may be seen as a direct consequence of the tomb robberies of the late New Kingdom and the subsequent abandonment of the necropolis by Ramesses XI. Associated with the evacuation of the Valley tombs may be discerned an official dismantling of the burials and a re-absorption into the economy of the precious commodities there interred. STUDIES IN THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE VALLEY OF THE KINGS, with particular reference to tomb robbery and the caching of the royal mummies (Volumes I—II) Volume I: Text by Carl Nicholas Reeves Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Oriental Studies University of Durham 1984 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. -

Mechanical Engineering in Ancient Egypt

Available online at www.ijarmate.com International Journal of Advanced Research in Management, Architecture, Technology and Engineering (IJARMATE) Vol. 2, Issue 4, April 2016. Mechanical Engineering in Ancient Egypt, Part XII: Stone Cutting Galal Ali Hassaan Emeritus Professor, Department of Mechanical design & Production, Faculty of Engineering, Cairo University, Egypt [email protected] Amenhotep III [3]. Lavigne (2006) stated that the ancient Abstract — This paper presents the 12 th part of a series of Egyptians had very high level of knowledge about working research papers aiming at studying the development of out and geometry. The purpose of her study was to understand mechanical engineering in ancient Egypt. It presents the the technical methods used throughout the Egyptian history techniques and technology used by ancient Egyptians to cut hard stones and produce very complex artifacts. The ancient giving more care to collect more information about tools and Egyptians used stone saws, drills and lathe turning and invented tool marks [4]. instrumentation to generate flat surfaces with accuracy better Storemyr et. al. (2007) presented the quarry landscapes than 0.005 mm and measure dimensions from 1.3 mm to 10 km. project for addressing the importance of ancient quarry landscapes and raising the awareness for the urgent need for Index Terms — Mechanical engineering in ancient Egypt, protecting such sites. Their work analyzed the condition and stone cutting, stone sawing. drilling and turning, stone surface legal status of the known ancient quarries in Egypt and the flattening, filleting of stone mating surfaces, dimensions measurement. threats facing them [5]. Loggia (2009) analyzed 17 tombs at Saqqara from the first dynasty and 25 tomb from Helwan from I. -

La Tombe De Youya Et Touyou (KV 46) James Edward Quibell

La tombe de Youya et Touyou (KV 46) James Edward Quibell Theodore Monroe Davis Tombe de Youya et Touyou (KV46) Entrée de la tombe (photographie de Howard Carter) Plan I/ La tombe a) l’architecture b) le mobilier funéraire et son emplacement c) les momies II/ Qui étaient Youya et Touyou ? a) les parents de Tiyi b) leurs nombreux titres c) leur origine et leur famille III/ L’activité de la tombe a) une tombe inachevée? b) la datation de l’enterrement c) les pillages La tombe L’architecture KV 55 Sceau de la nécropole thébaine: le chacal sur 9 captifs, faïence, Basse Epoque, N2217 Tombe de Youya et Touyou (KV 46) L’architecture ème Tombe de Youya et Touyou (KV 46) KV 21 (anonyme, 18 dynastie) Le mobilier funéraire et son emplacement Cercueil extérieur de Youya à patins, CG51001, bois doré, 3,64x1,61x2,16m Premier cercueil anthropoïde de Youya, CG51002, Deuxième et troisième cercueils anthropoïdes bois doré de Youya, CG51003 et CG51004, bois dore Cercueil extérieur à patins de Touyou, bois doré, CG51005 Premier cercueil anthropoïde de Touyou, bois doré, CG51006 Masque funéraire de Touyou, lin stuqué et doré, incrustations, CG51009 Masque funéraire de Youya, lin stuqué et Premier et deuxième cercueils doré, incrustations, anthropoïdes de Touyou, bois doré, CG51008 CG51006 et CG51007 Coffre à canopes de Touyou, CG51013 Coffre à canopes de Youya, CG51012 Coffres à chaouabtis et serviteurs funéraires Serviteur funéraire de de Youya, MET Touyou, JE 95361, bois doré Figurine magique du mur Nord de la Statuette magique de Youya avec 2 tombe de Thoutmosis