Journal of History and Cultures: Issue 10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Ancient Egypt

THE ROLE OF THE CHANTRESS ($MW IN ANCIENT EGYPT SUZANNE LYNN ONSTINE A thesis submined in confonnity with the requirements for the degm of Ph.D. Graduate Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civiliations University of Toronto %) Copyright by Suzanne Lynn Onstine (200 1) . ~bsPdhorbasgmadr~ exclusive liceacc aiiowhg the ' Nationai hiof hada to reproduce, loan, distnia sdl copies of this thesis in miaof#m, pspa or elccmnic f-. L'atm criucrve la propri&C du droit d'autear qui protcge cette thtse. Ni la thèse Y des extraits substrrntiets deceMne&iveatetreimprimCs ouraitnmcrtrepoduitssanssoai aut&ntiom The Role of the Chmaes (fm~in Ancient Emt A doctorai dissertacion by Suzanne Lynn On*, submitted to the Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations, University of Toronto, 200 1. The specitic nanire of the tiUe Wytor "cimûes", which occurrPd fcom the Middle Kingdom onwatd is imsiigated thrwgh the use of a dalabase cataloging 861 woinen whheld the title. Sorting the &ta based on a variety of delails has yielded pattern regatding their cbnological and demographical distribution. The changes in rhe social status and numbers of wbmen wbo bore the Weindicale that the Egyptians perceivecl the role and ams of the titk âiffefcntiy thugh tirne. Infomiation an the tities of ihe chantressw' family memkrs bas ailowed the author to make iderences cawming llse social status of the mmen who heu the title "chanms". MiMid Kingdom tifle-holders wverc of modest backgrounds and were quite rare. Eighteenth DMasty women were of the highest ranking families. The number of wamen who held the titk was also comparatively smaii, Nimeenth Dynasty women came [rom more modesi backgrounds and were more nwnennis. -

Arnold Bennett, Marie Corelli and the Interior Lives of Single Middle-Class Women, England, 1880-1914

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities 11-2003 A Novel Approach to History: Arnold Bennett, Marie Corelli and the Interior Lives of Single Middle-Class Women, England, 1880-1914 Sharon Crozier-De Rosa University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Law Commons Recommended Citation Crozier-De Rosa, Sharon, "A Novel Approach to History: Arnold Bennett, Marie Corelli and the Interior Lives of Single Middle-Class Women, England, 1880-1914" (2003). Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers. 1593. https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers/1593 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] A Novel Approach to History: Arnold Bennett, Marie Corelli and the Interior Lives of Single Middle-Class Women, England, 1880-1914 Abstract There are many ‘gaps’ or ‘silences’1 in women’s history – especially in relation to their interior lives. Historians seeking to penetrate the thoughts and emotions of ‘ordinary’ single middle-class women living during the Late Victorian and Edwardian years have a challenging task. These women rarely left personal documents for historians to analyse. Novels, particularly popular or bestselling novels, represent one pathway into this realm. Popular novels are numbered among the few written sources that are available to help historians to fill in some of the absences in the conventional historical record. -

Akhenaten: Dweller in Truth

Assignment Prompt: Write a 1500-word argument (about 4-5 pages double-spaced) about how you know that something is true. Final Paper: Akhenaten: Dweller in Truth In Naguib Mahfouz’s Akhenaten: Dweller in Truth, fourteen different stories of the heretic king Akhenaten are told. Some praise the king and his beliefs, some condemn him as a plague to Egypt, but all of the stories are unique in their detail and perspective. From Akhenaten’s teacher Ay, to his doctor Bento, to his wife Nefertiti, each character presents new and different details about Akhenaten’s life. In order to determine the truth about Akhenaten, each character’s statements must be considered closely, keeping in mind the biases and ulterior motivations that may exist. The full history of Akhenaten can only be found after examining his life through all fourteen perspectives. Some characteristics of Akhenaten are described similarly by nearly all of the characters in the novel. The agreement serves as reason to deem these things matters of fact. The characters agreed that Akhenaten was an effeminate-looking man, that he developed a belief in the One and Only God, that he claimed to have heard the voice of the One God, and that he preached a policy of absolute non-violence when he became pharaoh. Because so many of the details of Akhenaten’s life are unclear in the novel, these basic truths can be used to determine the truthfulness of certain characters. For example, the High Priest of Amun described Akhenaten as “ a man of questionable birth, effeminate and grotesque (13).” Ay, on the other hand, describes Akhenaten as, “dark, tall, and slender, with small, feminine features (28).” Based on these descriptions, it is clear that the High Priest did not like Akhenaten and that Ay was more sympathetic. -

Ancient Egyptian Chronology.Pdf

Ancient Egyptian Chronology HANDBOOK OF ORIENTAL STUDIES SECTION ONE THE NEAR AND MIDDLE EAST Ancient Near East Editor-in-Chief W. H. van Soldt Editors G. Beckman • C. Leitz • B. A. Levine P. Michalowski • P. Miglus Middle East R. S. O’Fahey • C. H. M. Versteegh VOLUME EIGHTY-THREE Ancient Egyptian Chronology Edited by Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, and David A. Warburton BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2006 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ancient Egyptian chronology / edited by Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, and David A. Warburton; with the assistance of Marianne Eaton-Krauss. p. cm. — (Handbook of Oriental studies. Section 1, The Near and Middle East ; v. 83) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-90-04-11385-5 ISBN-10: 90-04-11385-1 1. Egypt—History—To 332 B.C.—Chronology. 2. Chronology, Egyptian. 3. Egypt—Antiquities. I. Hornung, Erik. II. Krauss, Rolf. III. Warburton, David. IV. Eaton-Krauss, Marianne. DT83.A6564 2006 932.002'02—dc22 2006049915 ISSN 0169-9423 ISBN-10 90 04 11385 1 ISBN-13 978 90 04 11385 5 © Copyright 2006 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

Y6 Reading Comprehension (Answers)

When the railways arrived people travelled faster and The start of the railway age is further. The journey from accepted as 1825 when the London to Edinburgh took Stockton-Darlington line was 30 hours less than by coach. opened, first for coal wagons and then passengers. Improved transport meant raw materials such as coal and iron could be delivered faster and more cheaply. Farm machinery, for example, cost less, which led to cheaper food. Because the prices of food and other goods came down, The delivery of newspapers from demand for them increased. London and mail up and down the This meant more people were country was more efficient. More employed on the land and in interest was taken in what was factories. happening nationally and in the laws being passed by government. Rail tracks and stations, and railway engineering towns, such as Crewe, York and Doncaster, changed the landscape. People used this cheaper mode of travel to enjoy leisure time. As a result, seaside towns welcomed day trippers. The success of Stephenson’s steam engine, ‘Rocket’ in 1829 By 1900, Britain had 22,000 (it could go 30mph), led to miles of rail track constructed ‘Railway Mania’ and many new by men known as ‘navvies’. railway lines were built. In 1841, Isambard Kingdom Brunel completed the line from London to Bristol. Since it was called the Great Western Railway – GWR – people referred to it as ‘God’s Wonderful Railway’. © Copyright HeadStart Primary Ltd 2016 20 © Copyright HeadStart Primary Ltd 2016 21 General Characteristics Other Physical Features Spiders, scorpions, mites and ticks are all Unlike vertebrates, spiders do not have part of a large group of animals called a skeleton inside their bodies. -

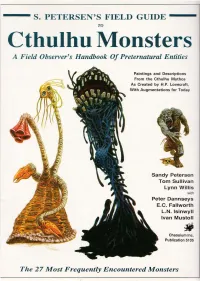

Cthulhu Monsters a Field Observer's Handbook of Preternatural Entities

--- S. PETERSEN'S FIELD GUIDE TO Cthulhu Monsters A Field Observer's Handbook Of Preternatural Entities Paintings and Descriptions From the Cthulhu Mythos As Created by H.P. Lovecraft, With Augmentations for Today Sandy Petersen Tom Sullivan Lynn Willis with Peter Dannseys E.C. Fallworth L.N. Isinwyll Ivan Mustoll Chaosium Inc. Publication 5105 The 27 Most Frequently Encountered Monsters Howard Phillips Lovecraft 1890 - 1937 t PETERSEN'S Field Guide To Cthulhu :Monsters A Field Observer's Handbook Of Preternatural Entities Sandy Petersen conception and text TOIn Sullivan 27 original paintings, most other drawings Lynn ~illis project, additional text, editorial, layout, production Chaosiurn Inc. 1988 The FIELD GUIDe is p «blished by Chaosium IIIC . • PETERSEN'S FIELD GUIDE TO CfHUU/U MONSTERS is copyrighl e1988 try Chaosium IIIC.; all rights reserved. _ Similarities between characters in lhe FIELD GUIDE and persons living or dead are strictly coincidental . • Brian Lumley first created the ChJhoniwu . • H.P. Lovecraft's works are copyright e 1963, 1964, 1965 by August Derleth and are quoted for purposes of ilIustraJion_ • IflCide ntal monster silhouelles are by Lisa A. Free or Tom SU/livQII, and are copyright try them. Ron Leming drew the illustraJion of H.P. Lovecraft QIId tlu! sketclu!s on p. 25. _ Except in this p«blicaJion and relaJed advertising, artwork. origillalto the FIELD GUIDE remains the property of the artist; all rights reserved . • Tire reproductwn of material within this book. for the purposes of personal. or corporaJe profit, try photographic, electronic, or other methods of retrieval, is prohibited . • Address questions WId commel11s cOlICerning this book. -

W534 Bird Coffin. by Amber Furmage

1 Life Cycle of an Object W534 – Bird Coffin Introduction W534, a bird coffin, currently resides in the animal case of the House of Death, The Egypt Centre, Swansea. The coffin came to Swansea in 1971, having been donated by the Wellcome Trustees. The Egypt Centre have dated it from between the Late Dynastic to the Graeco-Roman Period.1 It was constructed from a yellowish wood of poor quality with a coarse grain. Description Dimensions The bird coffin measures 436mm length by 139mm width at its largest point. The ventral cavity2 measures 330mm length by 68mm width, reaching a depth of 67mm from where the panel would be fitted. The head is 104mm height, making up 23.85% of the entire body. The beak then measures 22mm, 21.15% of the size of the head. The holes in the legs are of uneven proportions, both being 17mm in length but the right hole being 16mm width compared to the 12mm width of the left hole.3 Table 1 – Dimensions of W534 – Measurements taken by Author Feature Length Width Width Height Depth (largest) (smallest) Body 436mm 139mm Tail 104mm Head 80mm 104mm Beak 27mm 22mm Left leg hole 17mm 12mm Right leg hole 17mm 16mm Ventral cavity 330mm 68mm 39mm 67mm 1 The Egypt Centre, 2005. 2 See Figure 1. 3 See Figure 2 and Figure 3. Amber Furmage 2 Brief Description The piece is a yellowish wood4 carved to into a zoomorphic shape and coated in paint. The paint varies between features, some being black and other sections being red.5 The lack of paint on the top of the head6 may simply be an abrasion, however, due to the circular nature of the deficient, is perhaps more likely to be an area that had been covered up prior to painting and is now missing this element. -

The H. P. Lovecraft Tarot

The H. P. Lovecraft Tarot This interesting tarot deck was originally published in 1997 in a limited run and sold our fairly quickly, making it one of the most sought-after tarot decks on the market. This is one of the rare cases where you will actually hear these words: "Due to popular demand." This deck is the second printing from 2000, it is a blue deck, the 1st prinitng was red. Collectors take note! Each card in the deck is done in a dark, blue (1st printing) then red (2nd printing). Monochromatic decks appeal to me very much! The image is centered in the card and on the average has a lot of good detail which is easy enough to see. The border is also in the dark blue colour, but there is not enough contrast in this printing to clearly make out the text on the borders. You can see that it is there though, but you have to hold the cards fairly close to the light and angle them around a bit until you have made out each word. In the top center of the border is an eye. Pentacles are on the sides and the title at the bottom; the four corners have the suit icon itself on each card. Fortunately the little booklet has a legend in the back which shows the suit icons more clearly. In this deck, the figures of the Major Arcana are taken from various works of Lovecraft himself. The booklet that comes with this deck stresses that the Major Arcana cards have more power and influence over a reading than the Minor Arcana. -

Selected Proceedings from the 2003 Annual Conference of the International Leadership Association, November 6-8, Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico

Selected Proceedings from the 2003 annual conference of the International Leadership Association, November 6-8, Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico Origins of Leadership: Akhenaten, Ancient Leadership and Sacred Texts Leon F. “Skip” Rowland, Doctoral Candidate Leon F. “Skip” Rowland, “Origins of Leadership: Akhenaten, Ancient Leadership and Sacred Texts” presented at the International Leadership Association conference November 6-8 2003 in Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico. Available online at: http://www.ila-net.org/Publications/Proceedings/2003/lrowland.pdf - 1 - Introduction This paper presents an ancient international leader who used sacred texts to effect cultural change in all the major social institutions of ancient Egypt. The purpose of this paper is to help shape the future of leadership by presenting a form new to traditional leadership studies: that of an ancient Egyptian leader. This new face, Amenhotep IV, later known as Akhenaten, who founded a new place, Akhetaten, provided a new context for our study of international leadership. Guiding Questions Who was Akhenaten? What was the context of the times in which Akhenaten lived? What was Akhenaten’s religious heresy? What are sacred texts? What do they teach? How did Akhenaten use sacred texts to change Egyptian culture? What can researchers, practitioners, and educators learn from a study of Akhenaten? Methodology I conducted a cross-disciplinary literature review from anthropology, history, Egyptology, religion and spirituality, political science, social psychology, psychohistory, and leadership studies on the subject of Akhenaten and the Amarna Period of Ancient Egypt. I also reviewed the literature to understand the concept of “sacred texts” both in Egyptian culture and Western culture and consulted books of ancient literature to uncover the “sacred texts” of Egypt that would have conceivably been known to a Pharaoh during the 14th century B.C.E., after 1500 years of the written record – for example, the Instructions of Ptah-Hotep from around 2300 B.C.E. -

119 Original Article the GOLDEN SHRINES of TUTANKHAMUN

id9070281 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com Egyptian Journal of Archaeological and Restoration Studies "EJARS" An International peer-reviewed journal published bi-annually Volume 2, Issue 2, December - 2012: pp: 119-130 www. ejars.sohag-univ.edu.eg Original article THE GOLDEN SHRINES OF TUTANKHAMUN AND THEIR INTENDED BURIAL PLACE Soliman, R. Lecturer, Tourism guidance dept., Faculty of Archaeology & Tourism guidance, Misr Univ. for Sciences & Technology, 6th October city, Egypt E-mail: [email protected] Received 3/5/2012 Accepted 12/10/2012 Abstract The most famous tomb at the Valley of the Kings, KV 62 housed so far the most intact discovery of royal funerary treasures belonging to the eighteenth dynasty boy-king Tutankhamun. The tomb has a simple architectural plan clearly prepared for a non- royal burial. However, the hastily death of Tutankhamun at a young age caused his interment in such unusually small tomb. The treasures discovered were immense in number, art finesse and especially in the amount of gold used. Of these treasures the largest shrine of four shrines laid in the burial chamber needed to be dismantled and reassembled in the tomb because of its immense size. Clearly the black marks on this shrine helped in the assembly and especially the orientation in relation to the burial chamber. These marks are totally incorrect and prove that Tutankhamun was definitely intended to be buried in another tomb. Keywords: KV62, WV23, Golden shrines, Tutankhamun, Burial chamber, Orientation. 1. Introduction Tutankhamun was only nine and the real cause of his death remains years old when he got to throne; at that enigmatic. -

The Curse of the Pharaohs Free

FREE THE CURSE OF THE PHARAOHS PDF Elizabeth Peters | 320 pages | 29 Jun 2006 | Little, Brown Book Group | 9781845293871 | English | London, United Kingdom Assassin's Creed® Origins - The Curse Of The Pharaohs on Steam It's in Thebes, Egypt, and the esteemed archaeologist, Howard Carter, alongside his financial backer, Lord Carnarvon, holds a flickering match up to the darkness. They're underneath the Egyptian sand, at the mouth of the tomb of the Boy Pharaoh Tutankhamen. Hot air, trapped for s of years, escapes the ancient doorway. As my eyes grew accustomed to the light, details of the room within emerged slowly from the mist, strange animals, statues, and gold - everywhere the glint of gold. For the moment - an eternity it must have seemed to the others standing by - I was struck dumb with amazement, and when Lord Carnarvon, unable to stand the suspense any longer, inquired anxiously, 'Can you The Curse of the Pharaohs anything? After years and years of searching, the pair had found the final resting place of the famous child king, uncovering the most well-preserved tomb in Egypt's Valley of the Kings. As legend has it, there is an ancient curse associated with the The Curse of the Pharaohs and tombs of the Egyptian pharaohs. Disturbing these embalmed remains has been said to bring bad luck, illness and death. Shortly after unearthing King Tut's tomb, Carnarvon was found dead. A mosquito bite on his face had become infected, leading to deadly blood poisoning. And he would not be the only death, illness or unlucky occurrence associated with this expedition. -

DIALOGUES with the DEAD Comp

Comp. by: PG0844 Stage : Proof ChapterID: 0001734582 Date:13/10/12 Time:13:59:20 Filepath:d:/womat-filecopy/0001734582.3D1 OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRST PROOF, 13/10/2012, SPi DIALOGUES WITH THE DEAD Comp. by: PG0844 Stage : Proof ChapterID: 0001734582 Date:13/10/12 Time:13:59:20 Filepath:d:/womat-filecopy/0001734582.3D2 OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRST PROOF, 13/10/2012, SPi Comp. by: PG0844 Stage : Proof ChapterID: 0001734582 Date:13/10/12 Time:13:59:20 Filepath:d:/womat-filecopy/0001734582.3D3 OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRST PROOF, 13/10/2012, SPi Dialogues with the Dead Egyptology in British Culture and Religion 1822–1922 DAVID GANGE 1 Comp. by: PG0844 Stage : Proof ChapterID: 0001734582 Date:13/10/12 Time:13:59:20 Filepath:d:/womat-filecopy/0001734582.3D4 OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRST PROOF, 13/10/2012, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University press in the UK and in certain other countries # David Gange 2013 The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2013 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization.