Theory & Psychology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introductory Bibliography of Psychical Research

Appendix Introductory Bibliography of Psychical Research This annotated list is intended only to provide an entry into the vast lit- erature of serious psychical research. It is by no means complete or even comprehensive, and it reflects to some degree our personal preferences, although many if not most of our selections would probably also appear on similar lists compiled by other knowledgeable professionals. Many of the entries cited contain extensive bibliographies of their own. For additional references to some of the basic literature of the field, see http://www.pfly- ceum.org/106.html. Introductory and General Scientific Literature Broughton, Richard S. (1992). Parapsychology: The Controversial Science. New York: Ballantine. A good general introduction to the problems, findings, and implications of the science of parapsychology. Edge, Hoyt L., Morris, Robert L., Rush, Joseph H., & Palmer, John (1986). Founda- tions of Parapsychology: Exploring the Boundaries of Human Capability. Lon- don: Routledge & Kegan Paul. An advanced, textbook-style survey of methods and findings in modern parapsychology, emphasizing experimental studies. Krippner, Stanley (Ed.) (1977–1997). Advances in Parapsychological Research (8 vols.). An ongoing series reviewing recent research on a wide variety of top- ics of current interest to parapsychologists, including occasional bibliographic updates of the literature. Murphy, Michael (1992). The Future of the Body: Explorations into the Further Evolution of Human Nature. New York: Tarcher/Putnam. An extensive survey 645 646—Appendix and classification of phenomena bearing on the question of the evolution of human nature, as suggested in particular by latent, or as yet not fully real- ized, attributes and capacities for transcendence and transformation. -

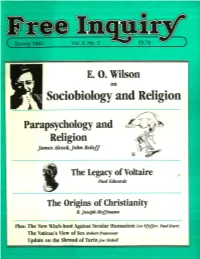

Update on the Shroud of Turin Joe Nickell SPRING 1985 ~In ISSN 0272-0701

LmAA_____., Fir ( Spring 1985 E. O. Wilson on Sociobiology and Religion Parapsychology and Religion James Alcock, John Beloff The Legacy of Voltaire Paul Edwards The Origins of Christianity R. Joseph Hoffmann Plus: The New Witch-hunt Against Secular Humanism Leo Pfeffer, Paul Kurtz The Vatican's View of Sex Robert Francoeur Update on the Shroud of Turin joe Nickell SPRING 1985 ~In ISSN 0272-0701 VOL. 5, NO. 2 Contents 3 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR 4 EDITORIALS 8 ON THE BARRICADES ARTICLES 10 Update on the Shroud of Turin Joe Nickell 11 The Vatican's View of Sex: The Inaccurate Conception Robert T. Francoeur 15 An Interview with E. O. Wilson on Sociobiology and Religion Jeffrey Saver RELIGION AND PARAPSYCHOLOGY 25 Parapsychology: The "Spiritual" Science James E. Alcock 36 Science, Religion and the Paranormal John Beloff 42 The Legacy of Voltaire (Part I) Paul Edwards 50 The Origins of Christianity: A Guide to Answering Fundamentalists R. Joseph Hoffmann BOOKS 57 Humanist Solutions Vern Bullough 58 Doomsday Environmentalism and Cancer Rodger Pirnie Doyle 59 IN THE NAME OF GOD 62 CLASSIFIED Editor: Paul Kurtz Associate Editors: Gordon Stein, Lee Nisbet, Steven L. Mitchell, Doris Doyle Managing Editor: Andrea Szalanski Contributing Editors: Lionel Abel, author, critic, SUNY at Buffalo; Paul Beattie, president, Fellowship of Religious Humanists; Jo-Ann Boydston, director, Dewey Center; Laurence Briskman, lecturer, Edinburgh University, Scotland; Vern Bullough, historian, State University of New York College at Buffalo; Albert Ellis, director, -

A Compendium of the Evidence for Psi1

European Journal of Parapsychology, 2003, 18, 33-52 A Compendium of the Evidence for Psi1 Adrian Parker Göran Brusewitz Department of Psychology, Swedish Society for Psychical Goteborg University Research Abstract: The article has the purpose of making readily available for scrutiny primary sources relating to studies that give evidence of psi-phenomena. Although the list is not offered as providing compelling evidence or “proof” of psi, it is meant to provide a strong case for a recruitment of resources. The effects are not marginal or non- replicable ones although it is clear that in many cases they appear to be dependent on certain experimenters and participants. The presentation includes sources relating to classical studies, meta-analyses of replication studies, the testing of high scoring subjects, and proof-orientated experiments, as well as the critical appraisal of this work. Where possible, web site addresses are given where this material is available and accessible. Theory driven research is needed especially concerning the nature of the experimenter effect. This compendium occurred as a result of what is perceived as a need to deal with the persistent claims concerning the lack of evidence for psi and thereby lack of justification for funding research and academic positions in parapsychology. It has been often asserted, sometimes with some measurable effect, that there is no evidence for psi, or if there is, it is so marginal and non-replicable and that resources should be instead allocated to the study of belief in the paranormal. The compendium presents evidence that appears to refute this assertion, The standard works summarizing this field, Wolman’s Handbook of Parapsychology and Kurtz´s The Skeptic’s Handbook of Parapsychology, are both long since out of date and out of print. -

GHOSTS MAKE NEWS! How Newspapers Report Psi Stories

Skeptical Inquirer • Vol. 14. No. 4 / Summer 1990 "V- v Satanic Myths and Urban Legends Thinking Critically and Creatively Piltdown, Paradigms & the Paranormal Survival Claims: Order Out of Chaos Quest for Auras / Biorhythms GHOSTS MAKE NEWS! How Newspapers Report Psi Stories Published by the Committee,for the Scientific investigation of Claims of the Paranormal THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER is the official journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal. Editor Kendrick Frazier. Editorial Board James E. Alcock, Martin Gardner, Ray Hyman, Philip J. Klass, Paul Kurtz, James Randi. Consulting Editors Isaac Asimov, William Sims Bainbridge, John R. Cole, Kenneth L. Feder, C. E. M. Hansel, E. C. Krupp, David F. Marks, Andrew Neher, James E. Oberg, Robert Sheaffer, Steven N. Shore. Managing Editor Doris Hawley Doyle. Business Manager Mary Rose Hays. Assistant Editor Andrea Szalanski. Art Valerie Ferenti-Cognetto. Chief Data Officer Richard Seymour. Computer Assistant Michael Cione. Typesetting Paul E. Loynes. Audio Technician Vance Vigrass. Librarian, Ranjit Sandhu. Staff Kimberly Gallo, Leland Harrington, Lynda Harwood (Asst. Public Relations Director), Sandra Lesniak, Alfreda Pidgeon, Kathy Reeves. Cartoonist Rob Pudim. The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Paul Kurtz, Chairman; philosopher, State University of New York at Buffalo. Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director. Barry Karr, Executive Director and Public Relations Director. Fellows of the Committee (partial list) James E. Alcock, psychologist, York Univ., Toronto; Eduardo Amaldi, physicist, University of Rome, Italy; Isaac Asimov, biochemist, author; Irving Biederman, psychologist, University of Minnesota; Susan Blackmore, psychologist, Brain Perception Laboratory, University of Bristol, England; Henri Broch, physicist, University of Nice, France; Mario Bunge, philosopher, McGill University; John R. -

Paranormal the SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Is the Official Journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal

the Skeptical Inquirer Vol. 13 No. 1 / Fall 1988 $6.00 Astrology & the Presidency Government & Gullibility NRC Examines Psi Claims The Intellectual Revolt Against Science Graphology: Write & Wrong Satan & Rock Music Published by the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER is the official journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal. Editor Kendrick Frazier. Editorial Board James E. Alcock, Martin Gardner, Ray Hyman, Philip J. Klass, Paul Kurtz, James Randi. Consulting Editors Isaac Asimov, William Sims Bainbridge, John R. Cole, Kenneth L. Feder, C. E. M. Hansel, E. C. Krupp, David F. Marks, Andrew Neher, James E. Oberg, Robert Sheaffer, Steven N. Shore. Managing Editor Doris Hawley Doyle. Public Relations Director Barry Karr. Business Manager Mary Rose Hays. Assistant Editor Andrea Szalanski. Production Lisa Mergler. Systems Programmer Richard Seymour. Typesetting Paul E. Loynes, Don Stoltman. Audio Technician Vance Vigrass. Librarian, Ranjit Sandhu. Staff Michael Cione, Crystal Folts, Leland Harrington, Laura Muench, Erin O'Hare, Alfreda Pidgeon, Kathy Reeves. Cartoonist Rob Pudim. The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Paul Kurtz, Chairman; philosopher, State University of New York at Buffalo. Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director. Mark Plummer, Executive Director. Fellows of the Committee James E. Alcock, psychologist, York Univ., Toronto; Eduardo Amaldi, physicist, University of Rome, Italy. Isaac Asimov, biochemist, author; Irving Biederman, psychologist, University of Minnesota; Susan Blackmore, psycholo gist, Brain Perception Laboratory, University of Bristol, England; Brand Blanshard, philosopher, Yale; Mario Bunge, philosopher, McGill University; Bette Chambers, A.H.A.; John R. Cole, anthropologist, Institute for the Study of Human Issues; F. -

Skeptical Responses to Psi Research

Skeptical Responses to Psi Research By Ted Goertzel and Ben Goertzel From Evidence for Psi: Thirteen Empirical Research Reports, edited by Damien Broderick and Ben Goertzel, McFarland and Company, 2015. Editors’ Note One of the peculiarities of psi research is that if any scientific work or publication on the topic gets attention at all outside the community of serious psi researchers, it is met by a barrage of derision from the community of self-styled psi “skeptics” (some of whom, it has been argued, might be better termed “denialists”). We consider it fairly likely that this edited volume will attract a familiar sort of negative attention from the psi skeptic community, and are certainly prepared to debate any of their critical responses to the evidence we have gathered here in a careful and public way. However, given the prominence of the “psi skeptic” phenomenon in the modern scientific and popular-media discussions of psi, we also deemed it worthwhile to include here an explicit analysis of the psi skeptic community itself and its weaknesses and motivations. Toward that end, we invited a brief chapter from a sociologist with expertise in both social movements and associated belief systems, and statistical data analysis—Ted Goertzel, who also happens to be the father of one of the editors. Ted has no historical connection with psi research, and brought to the project an attitude of healthy skepticism toward claims of the reality of psi phenomena. One of the thrusts of Ted’s research career has been the careful skeptical investigation of claims made by various parties based on statistical and other evidence, mostly related to social policy (the effect of capital punishment on homicide rates;1 the impact of welfare reform,2 etc.), but also including other topics such as UFO abductions.3 Ted’s initial chapter draft ultimately resulted in the jointly authored chapter you will find below. -

Paul Kurtz, CSICOP Grew and Inspired New Skep- Tical Groups, Both on the Local and the International Scenes

Jan Feb 13 2_SI new design masters 11/29/12 11:26 AM Page 12 The Modern Skeptical Movement Would Not Exist without Him RAY HYMAN result of these disagreements, Truzzi re- signed from CSICOP to pursue his own vision for a “skeptical” journal. Under the leadership of Paul Kurtz, CSICOP grew and inspired new skep- tical groups, both on the local and the international scenes. Paul was the right person at the right time. I believe that without Paul, we would not have had a successful skeptical movement. Al - though he was an academic and a philosopher, he defied the stereotypes for these occupations and was an ex- traordinary organizer, leader, and entre- preneur. Rarely, if ever, does one en- counter the collection of abilities in one The first meeting of the CSICOP Executive Council, in New York City in August 1977. Paul Kurtz is at head of person that Paul Kurtz possessed. Paul the table. was a scholar, philosopher, prolific au- The passing of Paul Kurtz represents a normal claims. Kurtz and Truzzi decided thor, editor, successful publisher, organ- major blow to the skeptical movement. that Paul and his colleagues should join izer, leader, and tireless advocate for the Without Paul Kurtz, the modern skep- SIR to form a national skeptical organi- truth. He was truly unique. tical movement, which began with the zation. Al though Truzzi did not consult —Ray Hyman is professor emeritus of founding of CSI (originally known as Gard ner, Randi, or me in making this psychology, University of Oregon, and a CSICOP), would not exist. -

Dossier: Martin Gardner

Dossier Adiós a Martin Gardner Ferrán Tarrasa Blanes l pasado 23 de mayo, la triste noticia de la muerte de sabe más sobre menos. Martin Gardner escribió con brillantez Martin Gardner me llegó a través de un correo electró- sobre matemáticas, lógica, filosofía, religión, literatura, relati- Enico en la lista de socios de ARP-SAPC, donde se vidad, mecánica cuántica, magia y, por supuesto, enlazaba un comentario que James Randi publicaba en su pseudociencia. blog. Martin Gardner había muerto el día anterior a la edad de A pesar de no recordar con claridad cuándo y cómo empecé 96 años. a leer a Martin Gardner, sí que recuerdo perfectamente cómo Para todos los miembros de la comunidad escéptica esa era devoraba con asombro sus artículos sobre temas tan vario- una noticia que nos llenaba de pesar. En mi caso, Martin pintos como códigos cifrados, las paradojas del infinito, ℵ0 y Gardner era el tercero de un grupo de autores, junto a los ya ℵ1, las curvas que llenan el espacio y los fractales, ð, e, desaparecidos Isaac Asimov y Carl Sagan, que, de muy joven, cicloides y braquistocronas, espirales, paseos aleatorios, me llevaron a admirar la ciencia y la razón y, al mismo números primos, topología, las coincidencias asombrosas que tiempo, me introdujeron en el escepticismo científico. no lo son tanto (lo asombroso sería que no hubiera coinciden- No recuerdo con claridad cuando compré (o más bien pedí cias asombrosas), los viajes a planilandia y a la cuarta que me compraran), mi primer libro de Martin Gardner, ni dimensión, magia e ilusionismo, o el arte de M. -

Critique of Serious Astrology / Science, Magic, & Metascience Velikovsky

the Skeptical Inquirer Critique of Serious Astrology / Science, Magic, & Metascience Velikovsky and China / Follow-ups on Ions, Hundredth Monkey VOL. XI NO. 3 / SPRING 1987 $5.00 Published by the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Skeptical Inquirer _ THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER is the official journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal. Editor Kendrick Frazier. Editorial Board James E. Alcock, Martin Gardner, Ray Hyman, Philip J. (Class, Paul Kurtz, James Randi. Consulting Editors Isaac Asimov, William Sims Bainbridge, John R. Cole, Kenneth L. Feder, C. E. M. Hansel, E. C. Krupp, Andrew Neher, James E. Oberg, Robert Sheaffer, Steven N. Shore. Managing Editor Doris Hawley Doyle. Public Relations Andrea Szalanski (director), Barry Karr. Production Editor Kelli Sechrist. Business Manager Mary Rose Hays. Systems Programmer Richard Seymour. Typesetting Paul E. Loynes. Audio Technician Vance Vigrass. Librarian, Peter Kalshoven. Staff Norman Forney, Mary Beth Gehrman, Diane Gerard, Erin O'Hare, Alfreda Pidgeon, Andrea Sammarco, Lori Van Amburgh. Cartoonist Rob Pudim. The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Paul Kurtz, Chairman; philosopher, State University of New York at Buffalo. Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director. Mark Plummer, Acting Executive Director. Fellows of the Committee James E. Alcock, psychologist, York Univ., Toronto; Eduardo Amaldi, physicist, University of Rome, Italy. Isaac Asimov, biochemist, author; Irving Biederman, psychologist, SUNY at Buffalo; Brand Blanshard, philosopher, Yale; Mario Bunge, philosopher, McGill University; Bette Chambers, A.H.A.; John R. Cole, anthropologist. Institute for the Study of Human Issues; F. H. C. Crick, biophysicist, Salk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla, Calif.; L. -

Downloads/Why-Is-There-A-Skeptical-Movement.Pdf, 66

URI GELLER AND THE RECEPTION OF PARAPSYCHOLOGY IN THE 1970S by JACOB OLDER GREEN B.A. The University of Chicago, 2009 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (History) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) July, 2018 © Jacob Older Green, 2018 The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, the thesis entitled: URI GELLER AND THE RECEPTION OF PARAPSYCHOLOGY IN THE 1970S submitted by Jacob Older Green in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Examining Committee: Joy Dixon, History Supervisor Robert Brain, History Supervisory Committee Member Alexei Kojevnikov Additional Examiner ii Abstract This paper investigates the controversy following the publication of work by scientists working at the Stanford Research Institute that claimed to show that the extraordinary mental powers of 1970s super psychic Uri Geller were real. The thesis argues that the controversy around Geller represented a shift in how skeptical scientists treated parapsychology. Instead of engaging with parapsychology and treating it as an incipient, if unpromising scientific discipline, which had been the norm since the pioneering work of J.B. Rhine in the 1930s, parapsychology's critics portrayed the discipline as a pseudoscience, little more than an attempt by credulous scientists to confirm their superstitious belief in occult psychic powers. The controversy around Geller also led to the creation of The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal (CSICOP), one of the first skeptical organizations specializing in investigating supposed instances of paranormal phenomena. -

A Skeptical Eye on Psi

A Skeptical Eye on Psi Eric{Jan Wagenmakers1, Ruud Wetzels1, Denny Borsboom1, Rogier Kievit2, & Han L. J. van der Maas1 1 University of Amsterdam 2 Cambridge University \I assume that the reader is familiar with the idea of extra-sensory per- ception, and the meaning of the four items of it, viz. telepathy, clairvoyance, precognition and psycho-kinesis. These disturbing phenomena seem to deny all our usual scientific ideas. How we should like to discredit them! Unfortunately the statistical evidence, at least for telepathy, is overwhelming." (Turing, 1950, p. 453). Research on extra-sensory perception or psi is contentious and highly polarized. On the one hand, its proponents believe that evidence for psi is overwhelming, and they support their case with a seemingly impressive series of experiments and meta-analyses. On the other hand, psi skeptics believe that the phenomenon does not exist, and the claimed statistical support is entirely spurious. We are firmly in the camp of the skeptics. However, the main goal of this chapter is not to single out and critique individual experiments on psi. Instead, we wish to highlight the many positive consequences that psi research has had on more traditional empirical research, an influence that we hope and expect will continue in the future. In the first section below, we assume that psi does not exist. Under this assump- tion, the entire field is spurious, and the literature on psi is a perfect reflection of what happens when a large group of researchers fool themselves into believing that an imagi- nary phenomenon is real. Thus, each and every effect is a fluke; all meta-analyses reflect bias, deception, or even outright fraud; none of the experiments are replicable; no practical application is ever successful. -

Should We Accept Arguments from Skeptics to Ignore the Psi Data? a Comment on Reber and Alcock’S “Searching for the Impossible”

Journal of Scientifi c Exploration,Vol. 33, No. 4, pp. 623–642, 2019 0892-3310/19 COMMENTARY Should We Accept Arguments from Skeptics to Ignore the Psi Data? A Comment on Reber and Alcock’s “Searching for the Impossible” GEORGE R. WILLIAMS [email protected] Submitted October 4, 2019; Accepted October 10, 2019; Published December 30, 2019 DOI: https://doi.org/10.31275/2019/1681 Copyright: Creative Commons CC-BY-NC Abstract—Reber and Alcock have recently made a sharp attack on the entire psi literature, and in particular a recent overview by Cardeña of the meta-analyses across various categories of psi. They claim the data are in- herently fl awed because of their disconnect with our current understand- ing of the world. As a result, they ignore the data and identify key scientifi c principles that they argue clash with psi. In this Commentary, I argue that these key principles are diffi cult to apply in areas where our understanding remains poor, especially quantum mechanics and consciousness. I also ex- plore how the psi data may fi t within these two domains. Introduction Recently, the journal American Psychologist published a paper by Etzel Cardeña that summarized the meta-analyses on various modes of psi and provided as well historical and theoretical background (Cardeña, 2018). Cardeña’s paper is most notable with its comprehensive approach. The presented meta-analyses give us perhaps the best bird’s-eye view of psi research to date. The combined studies include various modes or categories of psi, as well as different experimental designs for each one.