A Film by André Téchiné

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Press Notes

Strand Releasing presents CECILE DE FRANCE - PATRICK BRUEL - LUDIVINE SAGNIER JULIE DEPARDIEU - MATHIEU AMALRIC A SECRET A FILM BY CLAUDE MILLER Based on the Philippe Grimbert novel "Un Secret" (Grasset & Fasquelle), English translation : "Memory, A Novel" (Simon and Schuster) Winner : 2008 César Award for Julie Depardieu (Best Actress in a Supporting Role) Grand Prix des Amériques, 2007 Montreal World Film Festival In French with English subtitles 35mm/1.85/Color/Dolby DTS/110 min NY/National Press Contact: LA/National Press Contact: Sophie Gluck / Sylvia Savadjian Michael Berlin / Marcus Hu Sophie Gluck & Associates Strand Releasing phone: 212.595.2432 phone: 310.836.7500 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Please download photos from our website: www.strandreleasing.com/pressroom/pressroom.asp 2 CAST Tania Cécile DE FRANCE Maxime Patrick BRUEL Hannah Ludivine SAGNIER Louise Julie DEPARDIEU 37-year-old François Mathieu AMALRIC Esther Nathalie BOUTEFEU Georges Yves VERHOEVEN Commander Beraud Yves JACQUES Joseph Sam GARBARSKI 7-year-old Simon Orlando NICOLETTI 7-year-old François Valentin VIGOURT 14-year-old François Quentin DUBUIS Robert Robert PLAGNOL Hannah's mother Myriam FUKS Hannah's father Michel ISRAEL Rebecca Justine JOUXTEL Paul Timothée LAISSARD Mathilde Annie SAVARIN Sly pupil Arthur MAZET Serge Klarsfeld Eric GODON Smuggler Philippe GRIMBERT 2 3 CREW Directed by Claude MILLER Screenplay, adaptation, dialogues by Claude MILLER and Natalie CARTER Based on the Philippe -

Feature Films

FEATURE FILMS NEW BERLINALE 2016 GENERATION CANNES 2016 OFFICIAL SELECTION MISS IMPOSSIBLE SPECIAL MENTION CHOUF by Karim Dridi SPECIAL SCREENING by Emilie Deleuze TIFF KIDS 2016 With: Sofian Khammes, Foued Nabba, Oussama Abdul Aal With: Léna Magnien, Patricia Mazuy, Philippe Duquesne, Catherine Hiegel, Alex Lutz Chouf: It means “look” in Arabic but it is also the name of the watchmen in the drug cartels of Marseille. Sofiane is 20. A brilliant Some would say Aurore lives a boring life. But when you are a 13 year- student, he comes back to spend his holiday in the Marseille ghetto old girl, and just like her have an uncompromising way of looking where he was born. His brother, a dealer, gets shot before his eyes. at boys, school, family or friends, life takes on the appearance of a Sofiane gives up on his studies and gets involved in the drug network, merry psychodrama. Especially with a new French teacher, the threat ready to avenge him. He quickly rises to the top and becomes the of being sent to boarding school, repeatedly falling in love and the boss’s right hand. Trapped by the system, Sofiane is dragged into a crazy idea of going on stage with a band... spiral of violence... AGAT FILMS & CIE / FRANCE / 90’ / HD / 2016 TESSALIT PRODUCTIONS - MIRAK FILMS / FRANCE / 106’ / HD / 2016 VENICE FILM FESTIVAL 2016 - LOCARNO 2016 HOME by Fien Troch ORIZZONTI - BEST DIRECTOR AWARD THE FALSE SECRETS OFFICIAL SELECTION TIFF PLATFORM 2016 by Luc Bondy With: Sebastian Van Dun, Mistral Guidotti, Loic Batog, Lena Sukjkerbuijk, Karlijn Sileghem With: Isabelle Huppert, Louis Garrel, Bulle Ogier, Yves Jacques Dorante, a penniless young man, takes on the position of steward at 17-year-old Kevin, sentenced for violent behavior, is just let out the house of Araminte, an attractive widow whom he secretly loves. -

Pression” Be a Fair Description?

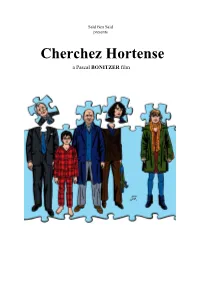

Saïd Ben Saïd presents Cherchez Hortense a Pascal BONITZER film Saïd Ben Saïd presents Cherchez Hortense A PASCAL BONITZER film Screenplay, adaptation and dialogues by AGNÈS DE SACY and PASCAL BONITZER with JEAN-PIERRE BACRI ISABELLE CARRÉ KRISTIN SCOTT THOMAS with the participation of CLAUDE RICH 1h40 – France – 2012 – SR/SRD – SCOPE INTERNATIONAL PR INTERNATIONAL SALES Magali Montet Saïd Ben Saïd Tel : +33 6 71 63 36 16 [email protected] [email protected] Delphine Mayele Tel : +33 6 60 89 85 41 [email protected] SYNOPSIS Damien is a professor of Chinese civilization who lives with his wife, Iva, a theater director, and their son Noé. Their love is mired in a mountain of routine and disenchantment. To help keep Zorica from getting deported, Iva gets Damien to promise he’ll go to his father, a state department official, for help. But Damien and his father have a distant and cool relationship. And this mission is a risky business which will send Damien spiraling downward and over the edge… INTERVIEW OF PASCAL BONITZER Like your other heroes (a philosophy professor, a critic, an editor), Damien is an intellectual. Why do you favor that kind of character? I know, that is seriously frowned upon. What can I tell you? I am who I am and my movies are also just a tiny bit about myself, though they’re not autobiographical. It’s not that I think I’m so interesting, but it is a way of obtaining a certain sincerity or authenticity, a certain psychological truth. Why do you make comedies? Comedy is the tone that comes naturally to me, that’s all. -

AFM 2014 +33 6 84 37 37 03 | [email protected]

PARIS OFFICE: 5, rue Darcet, 75017 Paris, France www.le-pacte.com Tel: +33 1 44 69 59 59 Fax: +33 1 44 69 59 42 COMPLETED VINCENT SCREENING AT AFM TO LIFE! WILD LIFE SUMMER NIGHTS TIMBUKTU IN PRODUCTION SALT OF THE EARTH VALLEY OF LOVE HIPPOCRATES THE BRAND NEW TESTAMENT THE KINDERGARTEN TEACHER QUEEN AND COUNTRY LIBRARY ATTENDING FROM NOVEMBER 5TH TO 11TH BOOTH NUMBER TBC Camille Neel | Head of Sales AFM 2014 +33 6 84 37 37 03 | [email protected] Wild Life Screening at AFM Click here for Promoreel Click here for press reviews SCREENING AT AFM BFI LONDON TOKYO FILM FESTIVAL FILM FESTIVAL Nov. 6th 1:00pm AMC Santa Monica 2 Official Selection Official Selection “Mathieu Kassovitz exudes total conviction in this story of a back-to-nature family torn apart when the mother decides to A FILM BY CEDRIC KAHN rejoin French society.” Variety Philippe Fournier, aka Paco, lives with his 6 and 7 year old sons, having decided not to give them back to their mother after she won custody of the children. As children and then adolescents, Okyesa and Tsali Fournier must live their lives in the shadows, assuming different identities, hunted by the police but always free and Original Title: Vie Sauvage on the move. From attics to farmhouses, caravans to communes, they live in harmony Cast: Mathieu Kassovitz, Céline Sallette with nature and their animals. They live with constant danger and fear, but also with Producer: Les Films du Lendemain the solidarity and bonds formed with friends met on the road, and the joys of living life off the grid. -

Téléchargez LE CATALOGUE 2021

DU 9 AU 13 JUIN 2021 3 ORGANISATION 5 ÉDITORIAUX 15 COMPÉTITION LONGS MÉTRAGES 33 COMPÉTITION COURTS MÉTRAGES 43 PANORAMA PRIX DU PUBLIC 55 LE MONDE ÉMOIS PRIX DU PUBLIC 63 JEUNESSE 67 PAR AMOUR SALLE DE JEUX DE LA MUSIQUE 71 CATLEYA LOUNGE BAR 75 CINÉ SWANN & PREMIERS RENDEZ-VOUS BRASSERIE VUE MER 83 RENCONTRES PROFESSIONNELLES 89 PROMENADE MARCEL PROUST - 14390 CABOURG INDEX 95 CASINO - ÉVÉNEMENTS REMERCIEMENTS RESTAURANT - BAR Entrée en salle de jeux réservée aux personnes majeures non interdites de jeux, sur présentation d’une pièce d’identité en cours de validité ou d’une carte Players Plus. Casino Partouche Cabourg, 300 000€, promenade Marcel Proust 14390 Cabourg, RCS 409268786 CAEN JOUER COMPORTE DES RISQUES : ISOLEMENT, ENDETTEMENT... APPELEZ LE 09 74 75 13 13 (APPEL NON SURTAXÉ) ORGAnIsATIOn FESTIVAL DU FILM DE CABOURG AssOCIATIOn LOI 1901 HÔTEL DE VILLE, PLACE BRUNO COQUATRIX, 14390 CABOURG PRÉsIDEnT DÉLÉGUÉE GÉnÉRALE RÉGIE AUDIOVIsUELLE Guillaume Laurant Suzel Pietri Hervé Drezen TRÉsORIER DIRECTRICE ARTIsTIQUE PROJECTIOnnIsTEs Olivier Pétré Marielle Pietri Sébastien Aubert Sylvain de Cressac sECRÉTAIRE REsPOnsABLE Sébastien Dumont Christophe Rivière DEs PARTEnARIATs Marco Redjil Sixte de Nanteuil MEMBREs BUREAU DE PRESSE Christine Citti REsPOnsABLE Alexandre Di Carlo Fabienne Henrot DEs JURYs ET TALEnTs Audrey Le Pennec Leslie Ricci Manuela Justine Brigitte Béliveau Jean-Louis Ripamonti REsPOnsABLE COMMUnICATIOn DIGITALE sECTIOn COURT MÉTRAGE Marie Grouin-Rigaux MEMBREs BIEnFAITRICEs COORDInATIOn CATALOGUE Emmanuelle Béart -

Un Film De Benoît Delépine& Gustave Kervern

LES FILMS DU WORSO ET NO MONEY PRODUCTIONS PRÉSENTENT BLANCHE DENIS CORINNE GARDIN PODALYDÈS MASIERO DE LA COMÉDIE-FRANÇAISE UN FILM DE BENOÎT DELÉPINE & GUSTAVE KERVERN VINCENT LACOSTE BENOÎT POELVOORDE BOULI LANNERS VINCENT DEDIENNE PHILIPPE REBBOT ET MICHEL HOUELLEBECQ LES FILMS DU WORSO et NO MONEY PRODUCTIONS présentent BLANCHE GARDIN DENIS PODALYDÈS CORINNE MASIERO DE LA COMÉDIE-FRANÇAISE un film deBEN OÎT DELÉPINE et GUSTAVE KERVERN 2020 / France / Couleur / Durée : 1h46 SORTIE LE 16 OCTOBRE Matériel presse téléchargeable sur : www.metropolefilms.com DISTRIBUTION RELATIONS PRESSE Métropole Films STAR PR 5360, Boulevard St-Laurent Bonne Smith Montréal - QC - H2T 1S1 Tél. : +1 416 488 4436 Tél. : 514 223 5511 Fax : +1 416 488 8438 [email protected] [email protected] SYNOPSIS Dans un lotissement du nord de la France, trois voisins sont en prise avec les nouvelles technologies et les réseaux sociaux. Il y a Marie, victime de chantage avec une sextape, Bertrand, dont la fille est harcelée au lycée, et Christine, chauffeur VTC dépitée de voir que les notes de ses clients refusent de décoller. Ensemble, ils décident de partir en guerre contre les géants d’internet. Une bataille foutue d’avance, quoique… Dans la lignée de votre travail cinématographique, EFFACER L’HISTORIQUE est à la fois un “film ENTRETIEN période gilets jaunes” et une critique drôle et cinglante de l’ère numérique. Quelle était votre idée première ? Comment naissent les films chez vous ? BENOÎT DELÉPINE Benoit Delépine - C’est notre 10ème film avec Gustave, on forme un duo d’amis et de cinéastes, et en fait, on met nos vies dans nos films. -

Névrotik Hôtel

On pose la page groupée de la brochure, on l’agrandit aux marges (du 2e repère à la marge de droite), on la dégroupe N° de spectacle en corps 55 Mot lié de la taille du n° Invasion ! Transgenre 29 Type de spectacle corps 14 Théâtre Taille du titre du spectacle en fonction musical de la longueur du titre 23 > 26 Névrotik Hôtel Tarifs, horaires à passer en deuxième janvier page Comédie musicale de chambre Dates en corps 14 Spectacle Mise en scène Michel Fau créé au Festival Auteur, Metteur en scène de Figeac en corps 17 2016 Voilà un acteur capable, avec la même jubilation, de jouer Tartuffe et Tante Geneviève, Racine et une diva emperlousée, voix de tête et poitrine en obus. Michel Fau, comédien Accroche en corps 14 virtuose, nous livre ici sa dernière folie de théâtre et d’acteur. Repère infos Racle Névrotik Hôtel Comédie musicale de chambre Mise en scène Michel Fau Tarif B de 9 à 25 € - Grand Théâtre - Mer 19h, Jeu, Ven, Sam 20h On copie le texte La Castafiore redessinée par Dubout, c’était dans Le Récital Emphatique. des 2 ou 4 pages brochure Dans Névrotik Hôtel, voilà Michel Fau en diva, que la vie a abandonnée aux mains d’un jeune groom dans la solitude d’une chambre d’hôtel très rose… on ne garde que les infos néces- Alors, il/elle chante : la vie d’hier, les lendemains incertains. saires On rit, on s’émeut. Artiste protéiforme et surdoué : Michel Fau ou le génie du Date, Titre, Noisette, travestissement. Générique, Texte présentation de la Avec Michel Fau, Antoine Kahan Piano Mathieu El Fassi page 2, Veillées, bords de scène, Accordéon -

Dossier Pédagogique

dossier pédagogique › Théâtre de l’Odéon 2O › 3O sept. O7 Illusions comiques texte et mise en scène OLIVIER PY y a r e t n o F n i a l A © › Rencontre à l’issue de la représentation du mardi 25 septembre O7 en présence d’Olivier Py et de l’équipe artistique › Service des relations avec le public scolaires et universitaires, associations d’étudiants réservation : O1 44 85 4O 39 – [email protected] actions pédagogiques : O1 44 85 4O 39 – [email protected] dossier également disponible sur http://www.theatre-odeon.fr. › Tarifs : 3O€ - 22€ - 12€ - 7.5€ (séries 1, 2, 3, 4) tarif scolaire : 11€ - 6€ (séries 2, 3) › Horaires : du mardi au samedi à 2Oh, le dimanche à 15h (relâche le lundi) › Odéon-Théâtre de l’Europe Théâtre de l’Odéon Place de l’Odéon Paris 6e Métro Odéon - RER Luxembourg Illusions comiques texte et mise en scène Olivier Py décor, costumes Pierre-André Weitz musique Stéphane Leach lumière Olivier Py, assisté de Bertrand Killy avec Olivier Balazuc, Michel Fau, Clovis Fouin, Philippe Girard, Mireille Herbstmeyer, Olivier Py et les musiciens Mathieu El Fassi, Pierre-André Weitz production : Centre dramatique national/Orléans-Loiret-Centre, le Théâtre du Rond-Point- Paris avec le soutien de la Fondation BNP Paribas, de la région Centre et du Fonds d’insertion pour jeunes artistes dramatiques créé le 29 mars 2OO6 au Centre dramatique national à Orléans Le texte de la pièce est édité chez Actes Sud-Papiers Durée 2h5O avec entracte Certaines parties de ce dossier sont tirées du dossier pédagogique réalisé par l’équipe des rela- tions avec le public du Théâtre National de Strasbourg. -

![Combattants Punks / Le Grand Soir De Gustave Kervern Et Benoît Delépine, France, 2012, 92 Min]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4064/combattants-punks-le-grand-soir-de-gustave-kervern-et-beno%C3%AEt-del%C3%A9pine-france-2012-92-min-1194064.webp)

Combattants Punks / Le Grand Soir De Gustave Kervern Et Benoît Delépine, France, 2012, 92 Min]

Document généré le 30 sept. 2021 00:48 Ciné-Bulles Combattants punks Le Grand Soir de Gustave Kervern et Benoît Delépine, France, 2012, 92 min Stéphane Defoy Volume 30, numéro 4, automne 2012 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/67506ac Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) Association des cinémas parallèles du Québec ISSN 0820-8921 (imprimé) 1923-3221 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer ce compte rendu Defoy, S. (2012). Compte rendu de [Combattants punks / Le Grand Soir de Gustave Kervern et Benoît Delépine, France, 2012, 92 min]. Ciné-Bulles, 30(4), 59–59. Tous droits réservés © Association des cinémas parallèles du Québec, 2012 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ en rond, comme si Kervern et Delépine ES avaient manqué d’inspiration. La conclu- U sion est faible et le récit multiplie les retour- nements de situation peu con vain cants. Il y a néanmoins quelques scènes mémorables, CRITIQ comme celle où les frères parlent simulta- nément de deux sujets à leur père, qui les dévisage, hagard et incapable de placer un mot. Le passage où celui-ci tente de persua- der les deux hommes qu’il n’est pas leur père dans l’espoir de se débarrasser d’eux est un autre moment de pur délice d’hu- mour absurde. -

The Shop Around the Corner Being 17 Cameraperson Seasons

Tuesday–Saturday: 11 am-10 pm 11 am-10 Tuesday–Saturday: pm Brunch: 10:30 am-3 Sunday (405) 235-6262 MUSEUM CAFE $5 (12 & under): Children $7 (13-18): Teen $7 ID): (with Students College $5 Members: FILM ADMISSION pm 12-5 Sunday: 10 am-5 pm Tuesday-Saturday: MUSEUM HOURS per person $3 (15 or more): Tours School per person $7 (15 or more): Tours $10 (6-18): Children $10 ID): (with Students College Free Members: MUSEUM ADMISSION (405) 236-3100 DRIVE COUCH 415 I I www.okcmoa.com Adults: $9 Adults: I I OKLAHOMA CITY, OK 73102 OKLAHOMA CITY, I Adults: $12 Adults: I www.okcmoa.com/cafe Closed Mondays and major holidays Mondays Closed I Children (5 & under): Free (5 & under): Children I Seniors (62+): $7 (62+): Seniors I Seniors (62+): $10 (62+): Seniors I I I Military (with ID): $5 ID): (with Military I Monday: 11 am-3 pm 11 am-3 Monday: Thursday: 10 am-9 pm Thursday: Museum Cafe Tea: 3-5 pm (Tues.-Fri.) Tea: Cafe Museum PRESENTED IN 35MM! I Senior Tours (15 or more): $6.50 per person (15 or more): Tours Senior Thursday, December 22 | 8 pm I BOTTLE ROCKET Wednesday, December 21 | 7:30 pm RUSHMORE Wednesday, December 28 | 7:30 pm after 5 pm AFTER 5: $5 ART Distinguished by its impeccably detailed compositions, deadpan wit, and meandering narrative, Bottle Rocket inaugurated the feature film careers of Captain of the fencing team, founder of the astronomy society, and writer-director of the epic Vietnam War drama, Heaven and Hell, fifteen-year-old Wes Anderson, Owen Wilson, and Luke Wilson, while laying the foundation for the development of Anderson’s now iconic film style. -

Gilles Lellouche INTERNATIONAL PRODUCTION NOTES

A FILM BY Gilles Lellouche INTERNATIONAL PRODUCTION NOTES CONTACTS INTERNATIONAL MARKETING INTERNATIONAL PUBLICITY Lucie MICHAUT Alexandre BOURG [email protected] [email protected] SYNOPSIS A group of 40-something guys, all on the verge of a mid-life crisis, decide to form their local pool’s first ever synchronized swimming team – for men. Braving the skepticism and ridicule of those around them and trained by a fallen champion trying to pull herself together, the group set out on an unlikely adventure, and on the way will rediscover a little self-esteem and a lot about themselves and each other. After Narco and The Players, Sink or Swim is the first film you’ve made as a solo director. Did you have difficulty launching a solo project, or was it just a question of timing? A little of both! Most of all, I needed to find a subject that really spoke to me and would enable me to make a film even more personal than Narco. As for The Players, that was a group project. I really enjoyed making both of those films, but neither was intimately linked to who I am. All of this took some time because after Narco, my “actors’ films” were the center of attention. How long has it taken to bring Sink or Swim to life? Five years. In fact, it was eight years ago that I began writing a script that already contained a few of the ideas in Sink or Swim. I wanted to examine the weariness – or perhaps the somewhat latent depression – that I sensed in people of my generation or even more generally in France. -

PRESS KIT § the Jury President § Presentation § an Exceptional Event § the Jury § the 2017 Nominees § Our Partners

MONDAY JANUARY 30TH, 2017 – PARIS LE LIDO PRESS KIT § The Jury President § Presentation § An exceptional event § The Jury § The 2017 Nominees § Our Partners January 2017 It is a great pleasure for us to have Ms Catherine Deneuve as this year's Jury President "This ceremony highlights the significance of French and international creations. Actors, performers, authors are going to be rewarded. As the President of the 2017 Jury, I'm happy to take part in this prestigious event and let the best ones win!!!” %CVJGTKPG&GPGWXG That France offers another way of experiencing culture in the world is your doing, dear artists. May you be honoured for it! “I used to make short films before photography swept me away. As a musician and film producer, I have only the highest esteem for each artistic universe. Creativity, boldness and excellence are the fruits which our Nation lovingly grows, hearkening back to Voltaire and establishing itself as the nation of freedom and expression of the arts. What a delight it is to revel in passions brought alive – may originality keep indifference forever at bay Celebrating such disciplines as literature, theatre, cinema and fashion, is also a way of acknowledging the power of attraction which France, the Nation of Lights, continues to enjoy. Actors, authors, directors, and many other unofficial ambassadors of all things "made in France", will take to the glittering legendary stage of the Lido, for a single evening dedicated to today's most promising talents and those who have earned the public's regard. Over the years, The Globes du Cristal have become an institution.