FHT-6-240713-2.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Continuity in Color: the Persistence of Symbolic Meaning in Myths, Tales, and Tropes

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern University Honors Program Theses 2016 Continuity in Color: The eP rsistence of Symbolic Meaning in Myths, Tales, and Tropes McKinley May Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation May, McKinley, "Continuity in Color: The eP rsistence of Symbolic Meaning in Myths, Tales, and Tropes" (2016). University Honors Program Theses. 170. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses/170 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Program Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Continuity in Color: The Persistence of Symbolic Meaning in Myths, Tales, and Tropes An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of Literature and Philosophy. By McKinley May Under the mentorship of Joe Pellegrino ABSTRACT This paper examines the symbolism of the colors black, white, and red from ancient times to modern. It explores ancient myths, the Grimm canon of fairy tales, and modern film and television tropes in order to establish the continuity of certain symbolisms through time. In regards to the fairy tales, the examination focuses solely on the lesser-known stories, due to the large amounts of scholarship surrounding the “popular” tales. The continuity of interpretation of these three major colors (black, white, and red) establishes the link between the past and the present and demonstrates the influence of older myths and beliefs on modern understandings of the colors. -

Seawood Village Movies

Seawood Village Movies No. Film Name 1155 DVD 9 1184 DVD 21 1015 DVD 300 348 DVD 1408 172 DVD 2012 704 DVD 10 Years 1175 DVD 10,000 BC 1119 DVD 101 Dalmations 1117 DVD 12 Dogs of Christmas: Great Puppy Rescue 352 DVD 12 Rounds 843 DVD 127 Hours 446 DVD 13 Going on 30 474 DVD 17 Again 523 DVD 2 Days In New York 208 DVD 2 Fast 2 Furious 433 DVD 21 Jump Street 1145 DVD 27 Dresses 1079 DVD 3:10 to Yuma 1124 DVD 30 Days of Night 204 DVD 40 Year Old Virgin 1101 DVD 42: The Jackie Robinson Story 449 DVD 50 First Dates 117 DVD 6 Souls 1205 DVD 88 Minutes 177 DVD A Beautiful Mind 643 DVD A Bug's Life 255 DVD A Charlie Brown Christmas 227 DVD A Christmas Carol 581 DVD A Christmas Story 506 DVD A Good Day to Die Hard 212 DVD A Knights Tale 848 DVD A League of Their Own 856 DVD A Little Bit of Heaven 1053 DVD A Mighty Heart 961 DVD A Thousand Words 1139 DVD A Turtle's Tale: Sammy's Adventure 376 DVD Abduction 540 DVD About Schmidt 1108 DVD Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter 1160 DVD Across the Universe 812 DVD Act of Valor 819 DVD Adams Family & Adams Family Values 724 DVD Admission 519 DVD Adventureland 83 DVD Adventures in Zambezia 745 DVD Aeon Flux 585 DVD Aladdin & the King of Thieves 582 DVD Aladdin (Disney Special edition) 496 DVD Alex & Emma 79 DVD Alex Cross 947 DVD Ali 1004 DVD Alice in Wonderland 525 DVD Alice in Wonderland - Animated 838 DVD Aliens in the Attic 1034 DVD All About Steve 1103 DVD Alpha & Omega 2: A Howl-iday 785 DVD Alpha and Omega 970 DVD Alpha Dog 522 DVD Alvin & the Chipmunks the Sqeakuel 322 DVD Alvin & the Chipmunks: Chipwrecked -

El Llegat Dels Germans Grimm En El Segle Xxi: Del Paper a La Pantalla Emili Samper Prunera Universitat Rovira I Virgili [email protected]

El llegat dels germans Grimm en el segle xxi: del paper a la pantalla Emili Samper Prunera Universitat Rovira i Virgili [email protected] Resum Les rondalles que els germans Grimm van recollir als Kinder- und Hausmärchen han traspassat la frontera del paper amb nombroses adaptacions literàries, cinema- togràfiques o televisives. La pel·lícula The brothers Grimm (2005), de Terry Gilli- am, i la primera temporada de la sèrie Grimm (2011-2012), de la cadena NBC, són dos mostres recents d’obres audiovisuals que han agafat les rondalles dels Grimm com a base per elaborar la seva ficció. En aquest article s’analitza el tractament de les rondalles que apareixen en totes dues obres (tenint en compte un precedent de 1962, The wonderful world of the Brothers Grimm), així com el rol que adopten els mateixos germans Grimm, que passen de creadors a convertir-se ells mateixos en personatges de ficció. Es recorre, d’aquesta manera, el camí invers al que han realitzat els responsables d’aquestes adaptacions: de la pantalla (gran o petita) es torna al paper, mostrant quines són les rondalles dels Grimm que s’han adaptat i de quina manera s’ha dut a terme aquesta adaptació. Paraules clau Grimm, Kinder- und Hausmärchen, The brothers Grimm, Terry Gilliam, rondalla Summary The tales that the Grimm brothers collected in their Kinder- und Hausmärchen have gone beyond the confines of paper with numerous literary, cinematographic and TV adaptations. The film The Brothers Grimm (2005), by Terry Gilliam, and the first season of the series Grimm (2011–2012), produced by the NBC network, are two recent examples of audiovisual productions that have taken the Grimm brothers’ tales as a base on which to create their fiction. -

The Contestants the Contestants

The Contestants The Contestants CYPRUS GREECE Song: Gimme Song: S.A.G.A.P.O (I Love You) Performer: One Performer: Michalis Rakintzis Music: George Theofanous Music: Michalis Rakintzis Lyrics: George Theofanous Lyrics: Michalis Rakintzis One formed in 1999 with songwriter George Michalis Rakintzis is one of the most famous Theofanous, Constantinos Christoforou, male singers in Greece with 16 gold and Dimitris Koutsavlakis, Filippos Constantinos, platinum records to his name. This is his second Argyris Nastopoulos and Panos Tserpes. attempt to represent his country at the Eurovision Song Contest. The group’s first CD, One, went gold in Greece and platinum in Cyprus and their maxi-single, 2001-ONE went platinum. Their second album, SPAIN Moro Mou was also a big hit. Song: Europe’s Living A Celebration Performer: Rosa AUSTRIA Music: Xasqui Ten Lyrics:Toni Ten Song: Say A Word Performer: Manuel Ortega Spain’s song, performed by Rosa López, is a Music:Alexander Kahr celebration of the European Union and single Lyrics: Robert Pfluger currency. Rosa won the hearts of her nation after taking part in the reality TV show Twenty-two-year-old Manuel Ortega is popular Operacion Triunfo. She used to sing at in Austria and his picture adorns the cover of weddings and baptisms in the villages of the many teenage magazines. He was born in Linz Alpujarro region and is now set to become one and, at the age of 10, he became a member of of Spain’s most popular stars. the Florianer Sängerknaben, one of the oldest boys’ choirs in Austria. CROATIA His love for pop music brought him back to Linz where he joined a group named Sbaff and, Song: Everything I Want by the age of 15, he had performed at over 200 Performer:Vesna Pisarovic concerts. -

Pdf Liste Totale Des Chansons

40ú Comórtas Amhrán Eoraifíse 1995 Finale - Le samedi 13 mai 1995 à Dublin - Présenté par : Mary Kennedy Sama (Seule) 1 - Pologne par Justyna Steczkowska 15 points / 18e Auteur : Wojciech Waglewski / Compositeurs : Mateusz Pospiezalski, Wojciech Waglewski Dreamin' (Révant) 2 - Irlande par Eddie Friel 44 points / 14e Auteurs/Compositeurs : Richard Abott, Barry Woods Verliebt in dich (Amoureux de toi) 3 - Allemagne par Stone Und Stone 1 point / 23e Auteur/Compositeur : Cheyenne Stone Dvadeset i prvi vijek (Vingt-et-unième siècle) 4 - Bosnie-Herzégovine par Tavorin Popovic 14 points / 19e Auteurs/Compositeurs : Zlatan Fazlić, Sinan Alimanović Nocturne 5 - Norvège par Secret Garden 148 points / 1er Auteur : Petter Skavlan / Compositeur : Rolf Løvland Колыбельная для вулкана - Kolybelnaya dlya vulkana - (Berceuse pour un volcan) 6 - Russie par Philipp Kirkorov 17 points / 17e Auteur : Igor Bershadsky / Compositeur : Ilya Reznyk Núna (Maintenant) 7 - Islande par Bo Halldarsson 31 points / 15e Auteur : Jón Örn Marinósson / Compositeurs : Ed Welch, Björgvin Halldarsson Die welt dreht sich verkehrt (Le monde tourne sens dessus dessous) 8 - Autriche par Stella Jones 67 points / 13e Auteur/Compositeur : Micha Krausz Vuelve conmigo (Reviens vers moi) 9 - Espagne par Anabel Conde 119 points / 2e Auteur/Compositeur : José Maria Purón Sev ! (Aime !) 10 - Turquie par Arzu Ece 21 points / 16e Auteur : Zenep Talu Kursuncu / Compositeur : Melih Kibar Nostalgija (Nostalgie) 11 - Croatie par Magazin & Lidija Horvat 91 points / 6e Auteur : Vjekoslava Huljić -

Year 7 Reading List

The Billericay School Year 7 Suggested Reading List While in Years 7, you should try to read a wide variety of types of books. Don’t just stick to one author, or one genre. Experiment with something new. That is one reason why this list is arranged in genre based sections. As well as reading books, don’t forget that newspapers and good magazines are also excellent reading material and will get you used to a range of reading experiences that will set you up well for GCSE and beyond. Not only will reading benefit you in your school subjects, but it will also broaden your knowledge and understanding of the world around you. It is recommended that you try to read at least one of the following texts each half term. The texts below are listed to complement what you will be learning during each half term. Please find the BAME authors and texts with BAME protagonists highlighted in pink and the LGBTQ+ authors and texts with LGBTQ+ representation are highlighted in orange. Year 7 Autumn 1 and 2 Gothic/Horror What’s the title? Who’s the author? What is it about? The Lie Tree Frances Hardinge The Lie Tree is set in the male- dominated Victorian scientific society, and tells the story of Faith Sunderly, a 14-year-old girl whose father is killed in mysterious circumstances after the family moves to the fictional island of Vane. Coraline Neil Gaiman While exploring her new home, a girl named Coraline discovers a secret door, behind which lies an alternate world that closely mirrors her own but, in many ways, is better. -

THE GETAWAY GIRL: a NOVEL and CRITICAL INTRODUCTION By

THE GETAWAY GIRL: A NOVEL AND CRITICAL INTRODUCTION By EMILY CHRISTINE HOFFMAN Bachelor of Arts in English University of Kansas Lawrence, Kansas 1999 Master of Arts in English University of Kansas Lawrence, Kansas 2002 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 2009 THE GETAWAY GIRL: A NOVEL AND CRITICAL INTRODUCTION Dissertation Approved: Jon Billman Dissertation Adviser Elizabeth Grubgeld Merrall Price Lesley Rimmel Ed Walkiewicz A. Gordon Emslie Dean of the Graduate College ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my appreciation to several people for their support, friendship, guidance, and instruction while I have been working toward my PhD. From the English department faculty, I would like to thank Dr. Robert Mayer, whose “Theories of the Novel” seminar has proven instrumental to both the development of The Getaway Girl and the accompanying critical introduction. Dr. Elizabeth Grubgeld wisely recommended I include Elizabeth Bowen’s The House in Paris as part of my modernism reading list. Without my knowledge of that novel, I am not sure how I would have approached The Getaway Girl’s major structural revisions. I have also appreciated the efforts of Dr. William Decker and Dr. Merrall Price, both of whom, in their role as Graduate Program Director, have generously acted as my advocate on multiple occasions. In addition, I appreciate Jon Billman’s willingness to take the daunting role of adviser for an out-of-state student he had never met. Thank you to all the members of my committee—Prof. -

DVD LIST 05-01-14 Xlsx

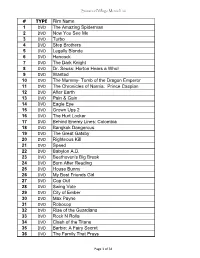

Seawood Village Movie List # TYPE Film Name 1 DVD The Amazing Spiderman 2 DVD Now You See Me 3 DVD Turbo 4 DVD Step Brothers 5 DVD Legally Blonde 6 DVD Hancock 7 DVD The Dark Knight 8 DVD Dr. Seuss: Horton Hears a Who! 9 DVD Wanted 10 DVD The Mummy- Tomb of the Dragon Emperor 11 DVD The Chronicles of Narnia: Prince Caspian 12 DVD After Earth 13 DVD Pain & Gain 14 DVD Eagle Eye 15 DVD Grown Ups 2 16 DVD The Hurt Locker 17 DVD Behind Enemy Lines: Colombia 18 DVD Bangkok Dangerous 19 DVD The Great Gatsby 20 DVD Righteous Kill 21 DVD Speed 22 DVD Babylon A.D. 23 DVD Beethoven's Big Break 24 DVD Burn After Reading 25 DVD House Bunny 26 DVD My Best Friends Girl 27 DVD Cop Out 28 DVD Swing Vote 29 DVD City of Ember 30 DVD Max Payne 31 DVD Robocop 32 DVD Rise of the Guardians 33 DVD Rock N Rolla 34 DVD Clash of the Titans 35 DVD Barbie: A Fairy Secret 36 DVD The Family That Preys Page 1 of 34 Seawood Village Movie List # TYPE Film Name 37 DVD Open Season 2 38 DVD Lakeview Terrace 39 DVD Fire Proof 40 DVD Space Buddies 41 DVD The Secret Life of Bees 42 DVD Madagascar: Escape 2 Africa 43 DVD Nights in Rodanthe 44 DVD Skyfall 45 DVD Changeling 46 DVD House at the End of the Street 47 DVD Australia 48 DVD Beverly Hills Chihuahua 49 DVD Life of Pi 50 DVD Role Models 51 DVD The Twilight Saga: Twilight 52 DVD Pinocchio 70th Anniversary Edition 53 DVD The Women 54 DVD Quantum of Solace 55 DVD Courageous 56 DVD The Wolfman 57 DVD Hugo 58 DVD Real Steel 59 DVD Change of Plans 60 DVD Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants 61 DVD Hansel & Gretel: Witch Hunters 62 DVD The Cold Light of Day 63 DVD Bride & Prejudice 64 DVD The Dilemma 65 DVD Flight 66 DVD E.T. -

DVD List As of 2/9/2013 2 Days in Paris 3 Idiots 4 Film Favorites(Secret

A LIST OF THE NEWEST DVDS IS LOCATED ON THE WALL NEXT TO THE DVD SHELVES DVD list as of 2/9/2013 2 Days in Paris 3 Idiots 4 Film Favorites(Secret Garden, The Witches, The Neverending Story, 5 Children & It) 5 Days of War 5th Quarter, The $5 A Day 8 Mile 9 10 Minute Solution-Quick Tummy Toners 10 Minute Solution-Dance off Fat Fast 10 Minute Solution-Hot Body Boot Camp 12 Men of Christmas 12 Rounds 13 Ghosts 15 Minutes 16 Blocks 17 Again 21 21 Jumpstreet (2012) 24-Season One 25 th Anniversary Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Concerts 28 Weeks Later 30 Day Shred 30 Minutes or Less 30 Years of National Geographic Specials 40-Year-Old-Virgin, The 50/50 50 First Dates 65 Energy Blasts 13 going on 30 27 Dresses 88 Minutes 102 Minutes That Changed America 127 Hours 300 3:10 to Yuma 500 Days of Summer 9/11 Commission Report 1408 2008 Beijing Opening Ceremony 2012 2016 Obama’s America A-Team, The ABCs- Little Steps Abandoned Abandoned, The Abduction About A Boy Accepted Accidental Husband, the Across the Universe Act of Will Adaptation Adjustment Bureau, The Adventures of Sharkboy & Lavagirl in 3-D Adventures of Teddy Ruxpin-Vol 1 Adventures of TinTin, The Adventureland Aeonflux After.Life Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-The Murder of Roger Ackroyd Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Sad Cypress Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-The Hollow Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Five Little Pigs Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Lord Edgeware Dies Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Evil Under the Sun Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Murder in Mespotamia Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Death on the Nile Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Taken at -

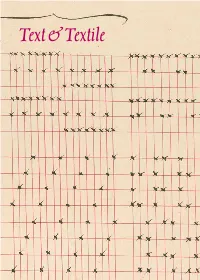

Text &Textile Text & Textile

1 TextText && TextileTextile 2 1 Text & Textile Kathryn James Curator of Early Modern Books & Manuscripts and the Osborn Collection, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library Melina Moe Research Affiliate, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library Katie Trumpener Emily Sanford Professor of Comparative Literature and English, Yale University 3 May–12 August 2018 Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library Yale University 4 Contents 7 Acknowledgments 9 Introduction Kathryn James 13 Tight Braids, Tough Fabrics, Delicate Webs, & the Finest Thread Melina Moe 31 Threads of Life: Textile Rituals & Independent Embroidery Katie Trumpener 51 A Thin Thread Kathryn James 63 Notes 67 Exhibition Checklist Fig. 1. Fabric sample (detail) from Die Indigosole auf dem Gebiete der Zeugdruckerei (Germany: IG Farben, between 1930 and 1939[?]). 2017 +304 6 Acknowledgments Then Pelle went to his other grandmother and said, Our thanks go to our colleagues in Yale “Granny dear, could you please spin this wool into University Library’s Special Collections yarn for me?” Conservation Department, who bring such Elsa Beskow, Pelle’s New Suit (1912) expertise and care to their work and from whom we learn so much. Particular thanks Like Pelle’s new suit, this exhibition is the work are due to Marie-France Lemay, Frances of many people. We would like to acknowl- Osugi, and Paula Zyats. We would like to edge the contributions of the many institu- thank the staff of the Beinecke’s Access tions and individuals who made Text and Textile Services Department and Digital Services possible. The Yale University Art Gallery, Yale Unit, and in particular Bob Halloran, Rebecca Center for British Art, and Manuscripts and Hirsch, and John Monahan, who so graciously Archives Department of the Yale University undertook the tremendous amount of work Library generously allowed us to borrow from that this exhibition required. -

Kinsella Feb 13

MORPHEUS: A BILDUNGSROMAN A PARTIALLY BACK-ENGINEERED AND RECONSTRUCTED NOVEL MORPHEUS: A BILDUNGSROMAN A PARTIALLY BACK-ENGINEERED AND RECONSTRUCTED NOVEL JOHN KINSELLA B L A Z E V O X [ B O O K S ] Buffalo, New York Morpheus: a Bildungsroman by John Kinsella Copyright © 2013 Published by BlazeVOX [books] All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without the publisher’s written permission, except for brief quotations in reviews. Printed in the United States of America Interior design and typesetting by Geoffrey Gatza First Edition ISBN: 978-1-60964-125-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2012950114 BlazeVOX [books] 131 Euclid Ave Kenmore, NY 14217 [email protected] publisher of weird little books BlazeVOX [ books ] blazevox.org 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 B l a z e V O X trip, trip to a dream dragon hide your wings in a ghost tower sails crackling at ev’ry plate we break cracked by scattered needles from Syd Barrett’s “Octopus” Table of Contents Introduction: Forging the Unimaginable: The Paradoxes of Morpheus by Nicholas Birns ........................................................ 11 Author’s Preface to Morpheus: a Bildungsroman ...................................................... 19 Pre-Paradigm .................................................................................................. 27 from Metamorphosis Book XI (lines 592-676); Ovid ......................................... 31 Building, Night ...................................................................................................... -

Sixth Form Iconic Reads

…… ……… SIXTH FORM …ICONIC…… READS…… Author Title Synopis Adams, Douglas The hitchhikers guide to the galaxy Ground breaking at the time. The answer is 42. Albom, Mitch The five people you meet in heaven The meaning of life - and life after death. Amis, Martin Money A dark tale of twentieth century consumerism. Angelou, Maya I know why the caged bird sings Autobiographical account of growing up in black America. Austen, Jane Pride and prejudice If you only read one classic, let it be this one. Banks, Iain The wasp factory A macabre, gothic horror story. Boyd, William Brazzaville beach If you are uncertain about chimpanzees, don’t read this book. Bradbury, Ray Fahrenheit 451 Books are burned by a special task force. Hauntingly prophetic. Bronte, Charlotte Jane Eyre Story of female rebellion and search for identity. Bronte, Emily Wuthering Heights A tragic, slightly morbid love story. Brookmyre, ChristopherPandaemonium An earthly battle between science and the supernatural, philosophy and faith, civilisation and savagery. The bookies are offering evens. Brooks, Kevin The bunker diary Unnerving exploration of your worst nightmare. Bukowski, Charles Post office Hank Chinaski, anti-hero, loser, he couldn’t care less about anything. Burgess, Anthony A clockwork orange Alarming vision of high technology, violence and authoritarianism. Calvino, Italo If on a winter’s night a traveller 10 different novels intertwine at the beginning of each book. Camus, Albert The outsider A beach murder leads to an execution. Meursault dies for truth. Capote, Truman In cold blood Al has to solve a crime, the evidence – 2 footprints and 4 bodies. Chandler, Raymond The big sleep Old man Sternwood, crippled and wheelchair bound is being given the squeeze by a blackmailer and wants Marlowe to make the problem go away.