Stockbridge Mohicans Past and Present

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Principal Indian Towns of Western Pennsylvania C

The Principal Indian Towns of Western Pennsylvania C. Hale Sipe One cannot travel far in Western Pennsylvania with- out passing the sites of Indian towns, Delaware, Shawnee and Seneca mostly, or being reminded of the Pennsylvania Indians by the beautiful names they gave to the mountains, streams and valleys where they roamed. In a future paper the writer will set forth the meaning of the names which the Indians gave to the mountains, valleys and streams of Western Pennsylvania; but the present paper is con- fined to a brief description of the principal Indian towns in the western part of the state. The writer has arranged these Indian towns in alphabetical order, as follows: Allaquippa's Town* This town, named for the Seneca, Queen Allaquippa, stood at the mouth of Chartier's Creek, where McKees Rocks now stands. In the Pennsylvania, Colonial Records, this stream is sometimes called "Allaquippa's River". The name "Allaquippa" means, as nearly as can be determined, "a hat", being likely a corruption of "alloquepi". This In- dian "Queen", who was visited by such noted characters as Conrad Weiser, Celoron and George Washington, had var- ious residences in the vicinity of the "Forks of the Ohio". In fact, there is good reason for thinking that at one time she lived right at the "Forks". When Washington met her while returning from his mission to the French, she was living where McKeesport now stands, having moved up from the Ohio to get farther away from the French. After Washington's surrender at Fort Necessity, July 4th, 1754, she and the other Indian inhabitants of the Ohio Val- ley friendly to the English, were taken to Aughwick, now Shirleysburg, where they were fed by the Colonial Author- ities of Pennsylvania. -

A-Brief-History-Of-The-Mohican-Nation

wig d r r ksc i i caln sr v a ar ; ny s' k , a u A Evict t:k A Mitfsorgo 4 oiwcan V 5to cLk rid;Mc-u n,5 3 ss l Y gew y » w a. 3 k lz x OWE u, 9g z ca , Z 1 9 A J i NEI x i c x Rat 44MMA Y t6 manY 1 YryS y Y s 4 INK S W6 a r sue`+ r1i 3 My personal thanks gc'lo thc, f'al ca ° iaag, t(")mcilal a r of the Stockbridge-IMtarasee historical C;orrunittee for their comments and suggestions to iatataraare tlac=laistcatic: aal aac c aracy of this brief' history of our people ta°a Raa la€' t "din as for her c<arefaal editing of this text to Jeff vcic.'of, the rlohican ?'yews, otar nation s newspaper 0 to Chad Miller c d tlac" Land Resource aM anaagenient Office for preparing the map Dorothy Davids, Chair Stockbridge -Munsee Historical Committee Tke Muk-con-oLke-ne- rfie People of the Waters that Are Never Still have a rich and illustrious history which has been retrained through oral tradition and the written word, Our many moves frorn the East to Wisconsin left Many Trails to retrace in search of our history. Maanv'rrails is air original design created and designed by Edwin Martin, a Mohican Indian, symbol- izing endurance, strength and hope. From a long suffering proud and deternuned people. e' aw rtaftv f h s is an aatathCutic basket painting by Stockbridge Mohican/ basket weavers. -

ABSTRACT Identifying with the Lowly: Jonathan Edwards, Charity, and The

ABSTRACT Identifying with the Lowly: Jonathan Edwards, Charity, and the Stockbridge Mission. Nicolas G. Peterson Director: Thomas S. Kidd Jonathan Edwards is commonly thought of as a cold but brilliant theologian, a fire- breathing railer, quick to use his genius with words to reprove, a man bookishly removed from the daily concerns of life. However, recent scholarship incorporating a larger corpus of his works, only now easily accessible, has revealed a more multifaceted man, a pastor who, in fact, preached and wrote volumes on Divine Love and its outworking in Christian charity. He laid both the philosophic and aesthetic groundwork to convince the Christian of the necessity of a charitable disposition and its required fruit. Throughout his first thirty years as a pastor, he returned often to the imperatives of charity. This thesis highlights the ways in which he specifically addressed the need for active charity to the neediest in the community, the poor and disenfranchised no matter their race. As he identified an increasingly pervasive lust for gain in the colonies and in Northampton he censured such selfish motives through his pastoring and preaching. After years of wrangling over such issues, his teaching tended to emphasize that the most practical way to tune our hearts to a joyful obedience of this duty is to reject selfish ambition and to identify with the lowly. Not only did Edwards teach these virtues often in both his New York and Northampton pulpits, but he personally and tirelessly worked for the cause of the poor. This thesis will show that Edwards’ choice to minister at Stockbridge after his dismissal at Northampton was consistent with his focus on charity throughout his life and exemplifies identifying with the lowly and despised of society. -

Guilford Collegian

UBRARY ONLY FOR USE IN THE Guilford College Library Class 'Boo v ' 5 Accessio n \S4o3 Gift FOR USE IN THE LIBRARY ONLY Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill http://www.archive.org/details/guilfordcollegia05guil : ' .' •/ ;: ''"V W . r<V iL •<£$%• i - -—-: | tei T'H E - i?i%i^sr r i '' THE GUILFORD COLLEGIAN. OUR TRADE IN Improved New Lee and Patron Cooking Stoves AND NEW LEE AND RICHMOND RANGES Has increased to such an extent that we are now buying them in car load lots. THEY ARE WARRANTED TO BE FIRST QUALITY. Our prices are on the " Live and let live plan," and they account, in part, for the popularity of these Stoves. WMIPCILB!) H)ARP;WAfti <$®» GREENSBORO, N. C. SUMMER VACATION. ILIFF'S Every college man will need to take away in his crip this summer one or two of the latest college song books, which contain all the new and popular University airs We give here the complete list, and any volume will be c ent, postpaid, to any address on receipt of price. THE NEW HARVARD SONG ROOK— All the new Harvard songs of the last three years, with some old favorites. 92 pages. Price $1. 00 postpaid. _ College Songs.—Over 200,000 sold. Containing 91 songs- -all of the old favorites, as well as the new ones: "Don't Forget Dar's a Weddin' To-Night," "DiHe who couldn't Dance,'' "Good-by, my Little Lady," etc Paper, 50 cents. University Songs.—Contains songs of the older colleges — Harvard, Vale, Columbia, Princeton, Rrown, Dartmouth, Williams Bowdoin, Union, and Rutgers Cloth; $2.50. -

The Decline of Algonquian Tongues and the Challenge of Indian Identity in Southern New England

Losing the Language: The Decline of Algonquian Tongues and the Challenge of Indian Identity in Southern New England DA YID J. SIL VERMAN Princeton University In the late nineteenth century, a botanist named Edward S. Burgess visited the Indian community of Gay Head, Martha's Vineyard to interview native elders about their memories and thus "to preserve such traditions in relation to their locality." Among many colorful stories he recorded, several were about august Indians who on rare, long -since passed occasions would whisper to one another in the Massachusett language, a tongue that younger people could not interpret. Most poignant were accounts about the last minister to use Massachusett in the Gay Head Baptist Church. "While he went on preaching in Indian," Burgess was told, "there were but few of them could know what he meant. Sometimes he would preach in English. Then if he wanted to say something that was not for all to hear, he would talk to them very solemnly in the Indian tongue, and they would cry and he would cry." That so few understood what the minister said was reason enough for the tears. "He was asked why he preached in the Indian language, and he replied: 'Why to keep up my nation.' " 1 Clearly New England natives felt the decline of their ancestral lan guages intensely, and yet Burgess never asked how they became solely English speakers. Nor have modem scholars addressed this problem at any length. Nevertheless, investigating the process and impact of Algonquian language loss is essential for a fuller understanding Indian life during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and even beyond. -

Jonathan Edwards' Life: More Than a Sermon

Jonathan Edwards 1 Running Head: JONATHAN EDWARDS Jonathan Edwards' Life: More Than a Sermon Matthew Ryan Martin A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2003 Jonathan Edwards 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. Chairman of Thesis ~~Ha.rVeY man, Th.D. .. Committee Member Branson Woodard Jr., D.A. Committee Member JrJdy,/, ,.IS ndlin, Ph.D. ASSIstant Honors Program Director Jonathan Edwards 3 Abstract Jonathan Edwards, born, (1703-1758), was a great man. He is often known only for a sermon, "Sinners in the Aands of an Angry God." This is unfortunate because followers of Christ should know this man's life. This paper focuses on Jonathan Edwards as a godly family man and on his missiological work. An emphasis is not carefully analyzed by many. The research for this essay originated from the author's desire to know more about Mr. Edwards. The texts studied are The works ofJonathan Edwards, along with many scholarly books and essays. The main modern books used are from Perry Miller and Elizabeth Dodds. All in all, the following research adds clarity and context to Edwards' legacy and to its enduring value to Christians. Jonathan Edwards 4 Jonathan Edwards' Life: More Than a Sermon Introduction Even after growing up in the church as a child, the writer did not discover the name of Jonathan Edwards until the beginning of his high school freshman year. -

A Chronology of Edwards' Life and Writings

A CHRONOLOGY OF EDWARDS’ LIFE AND WRITINGS Compiled by Kenneth P. Minkema This chronology of Edwards's life and times is based on the dating of his early writings established by Thomas A. Schafer, Wallace E. Anderson, and Wilson H. Kimnach, supplemented by volume introductions in The Works of Jonathan Edwards, by primary sources dating from Edwards' lifetime, and by secondary materials such as biographies. Attributed dates for literary productions indicate the earliest or approximate points at which Edwards probably started them. "Miscellanies" entries are listed approximately in numerical groupings by year rather than chronologically; for more exact dating and order, readers should consult relevant volumes in the Edwards Works. Entries not preceded by a month indicates that the event in question occurred sometime during the calendar year under which it listed. Lack of a pronoun in a chronology entry indicates that it regards Edwards. 1703 October 5: born at East Windsor, Connecticut 1710 January 9: Sarah Pierpont born at New Haven, Connecticut 1711 August-September: Father Timothy serves as chaplain in Queen Anne's War; returns home early due to illness 1712 March-May: Awakening at East Windsor; builds prayer booth in swamp 1714 August: Queen Anne dies; King George I crowned November 22: Rev. James Pierpont, Sarah Pierpont's father, dies 1716 September: begins undergraduate studies at Connecticut Collegiate School, Wethersfield 2 1718 February 17: travels from East Windsor to Wethersfield following school “vacancy” October: moves to -

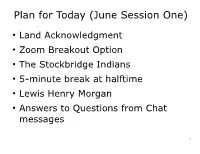

June Session One Presentation

Plan for Today (June Session One) ● Land Acknowledgment ● Zoom Breakout Option ● The Stockbridge Indians ● 5-minute break at halftime ● Lewis Henry Morgan ● Answers to Questions from Chat messages 1 “Part 2” Fridays in June Greater detail on Algonkian culture and values ● Less emphasis on history, more emphasis on values, many of which persist to the present day ● Stories and Myths – Possible Guest Appearance(s) – Joseph Campbell's The Power of Myth ● Current/Recent Fiction 2 “Part 3” Fall OLLI Course Deeper dive into philosophy ● Cross-pollination (Interplay of European values and customs with those of the Native Americans) ● Comparison of the Theories of Balance ● Impact of the Little Ice Age ● Enlightenment Philosophers' misapprehension of prelapsarian “Primitives” ● Lessons learned and Opportunities lost ● Dealing with climate change, income inequality, and intellectual property ● Steady State Economics; Mutual Aid; DIY-bio 3 (biohacking) and much more Sources for Today (in addition to the two books recommended) ● Grace Bidwell Wilcox (1891-1968) ● Richard Bidwell Wilcox “John Trusler's Conversations with the Wappinger Chiefs on Civilization” c. 1810 ● Patrick Frazier The Mohicans of Stockbridge ● Daniel Noah Moses The Promise of Progress: The Life and Work of Lewis Henry Morgan 4 5 Indigenous Cultures Part 2 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus ● People arrived in the Americas earlier than had been thought ● There were many more people in the Americas than in previous estimates ● American cultures were far more sophisticated -

HISTORY of MONTGOMERY COUNTY. Ments Extended From

'20 HISTORY OF MONTGOMERY COUNTY. ments extended from New Amsterdam (New York) on the south, to Albany on the north, mainly along the Hudson river, but there are well defined evidences of their early occupation of what is now western Ver- mont, and also part of Massachusetts; and at the same time they also advanced their outposts along the Mohawk valley toward the region of old Tryon county. CHAPTER III. The Indian Occupation — The Iroquois Confederacy,— The Five and Six Nations of Indians — Location and Names — Character and Power of the League — Social and Domestic Habits—The Mohawks — Treatment of the Jesuit Missionaries — Discourag- ing Efforts at Civilization—Names of Missionaries—Alliance with the English—Down- lall of the Confederacy. Q FTER the establishment of the Dutch in the New Netherlands the / \ region now embraced within the state of New York was held by three powers — one native and two foreign. The main colonies of the French (one of the powers referred to) were in the Canadas, but through the zeal of the Jesuit missionaries their line of possessions had been extended south and west of the St. Lawrence river, and some attempts at colonization had been made, but as yet with only partial success. In the southern and eastern portion of the province granted pom to the Duke of York were the English, who with steady yet sure ad- ual vances were pressing settlement and civilization westward and gradually nearing the French possessions. The French and English were at this time, and also for many years afterwards, conflicting powers, each study- ing for the mastery on both sides of the Atlantic; and with each suc- ceeding outbreak of war in the mother countries, so there were renewed hostilities between their American colonies. -

THE INDIANS of LENAPEHOKING (The Lenape Or Delaware Indians)

THE INDIANS OF LENAPEHOKING (The Lenape or Delaware Indians) By HERBERT C.KRAFT NCE JOHN T. KRAFT < fi Seventeenth Century Indian Bands in Lenapehoking tN SCALE: 0 2 5 W A P P I N Q E R • ' miles CONNECTICUT •"A. MINISS ININK fy -N " \ PROTO-MUNP R O T 0 - M U S E*fevj| ANDS; Kraft, Herbert rrcrcr The Tndians nf PENNSYLVANIA KRA hoking OKEHOCKING >l ^J? / / DELAWARE DEMCO NO . 32 •234 \ RINGVyOOP PUBLIC LIBRARY, NJ N7 3 6047 09045385 2 THE INDIANS OF LENAPEHOKING by HERBERT C. KRAFT and JOHN T. KRAFT ILLUSTRATIONS BY JOHN T. KRAFT 1985 Seton Hall University Museum South Orange, New Jersey 07079 145 SKYLAND3 ROAD RINGWOOD, NEW JERSEY 07456 THE INDIANS OF LENAPEHOKING: Copyright(c)1985 by Herbert C. Kraft and John T. Kraft, Archaeological Research Center, Seton Hall University Museum, South Orange, Mew Jersey. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book--neither text, maps, nor illustrations--may be reproduced in any way, including but not limited to photocopy, photograph, or other record without the prior agreement and written permission of the authors and publishers, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address Dr. Herbert C. Kraft, Archaeological Research Center, Seton Hall University Museum, South Orange, Mew Jersey, 07079 Library of Congress Catalog Number: 85-072237 ISBN: 0-935137-00-9 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The research, text, illustrations, and printing of this book were made possible by a generous Humanities Grant received from the New Jersey Department of Higher Education in 1984. -

LENAPE VILLAGES of DELAWARE COUNTY By: Chris Flook

LENAPE VILLAGES OF DELAWARE COUNTY By: Chris Flook After the signing of the Treaty of Greenville in 1795, many bands of Lenape (Delaware) Native Americans found themselves without a place to live. During the previous 200 years, the Lenape had been pushed west from their ancestral homelands in what we now call the Hudson and Delaware river valleys first into the Pennsylvania Colony in the mid1700s and then into the Ohio Country around the time of the American Revolution. After the Revolution, many Natives living in what the new American government quickly carved out to be the Northwest Territory, were alarmed of the growing encroachment from white settlers. In response, numerous Native groups across the territory formed the pantribal Western Confederacy in an attempt to block white settlement and to retain Native territory. The Western Confederacy consisted of warriors from approximately forty different tribes, although in many cases, an entire tribe wasn’t involved, demonstrating the complexity and decentralized nature of Native American political alliances at this time. Several war chiefs led the Western Confederacy’s military efforts including the Miami chief Mihšihkinaahkwa (Little Turtle), the Shawnee chief Weyapiersenwah (Blue Jacket), the Ottawa chief Egushawa, and the Lenape chief Buckongahelas. The Western Confederacy delivered a series of stunning victories over American forces in 1790 and 1791 including the defeat of Colonel Hardin’s forces at the Battle of Heller’s Corner on October 19, 1790; Hartshorn’s Defeat on the following day; and the Battle of Pumpkin Fields on October 21. On November 4 1791, the forces of the territorial governor General Arthur St. -

Ramapough/Ford the Impact and Survival of an Indigenous

Antioch University AURA - Antioch University Repository and Archive Student & Alumni Scholarship, including Dissertations & Theses Dissertations & Theses 2015 Ramapough/Ford The mpI act and Survival of an Indigenous Community in the Shadow of Ford Motor Company’s Toxic Legacy Chuck Stead Antioch University - New England Follow this and additional works at: http://aura.antioch.edu/etds Part of the American Studies Commons, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, Environmental Health Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, Toxicology Commons, United States History Commons, and the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Stead, Chuck, "Ramapough/Ford The mpI act and Survival of an Indigenous Community in the Shadow of Ford Motor Company’s Toxic Legacy" (2015). Dissertations & Theses. 200. http://aura.antioch.edu/etds/200 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student & Alumni Scholarship, including Dissertations & Theses at AURA - Antioch University Repository and Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations & Theses by an authorized administrator of AURA - Antioch University Repository and Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Department of Environmental Studies DISSERTATION COMMITTEE PAGE The undersigned have examined the dissertation entitled: Ramapough/Ford: The Impact and Survival of an Indigenous Community in the Shadow of Ford Motor Company’s Toxic Legacy presented by Chuck