Ramapough/Ford the Impact and Survival of an Indigenous

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Principal Indian Towns of Western Pennsylvania C

The Principal Indian Towns of Western Pennsylvania C. Hale Sipe One cannot travel far in Western Pennsylvania with- out passing the sites of Indian towns, Delaware, Shawnee and Seneca mostly, or being reminded of the Pennsylvania Indians by the beautiful names they gave to the mountains, streams and valleys where they roamed. In a future paper the writer will set forth the meaning of the names which the Indians gave to the mountains, valleys and streams of Western Pennsylvania; but the present paper is con- fined to a brief description of the principal Indian towns in the western part of the state. The writer has arranged these Indian towns in alphabetical order, as follows: Allaquippa's Town* This town, named for the Seneca, Queen Allaquippa, stood at the mouth of Chartier's Creek, where McKees Rocks now stands. In the Pennsylvania, Colonial Records, this stream is sometimes called "Allaquippa's River". The name "Allaquippa" means, as nearly as can be determined, "a hat", being likely a corruption of "alloquepi". This In- dian "Queen", who was visited by such noted characters as Conrad Weiser, Celoron and George Washington, had var- ious residences in the vicinity of the "Forks of the Ohio". In fact, there is good reason for thinking that at one time she lived right at the "Forks". When Washington met her while returning from his mission to the French, she was living where McKeesport now stands, having moved up from the Ohio to get farther away from the French. After Washington's surrender at Fort Necessity, July 4th, 1754, she and the other Indian inhabitants of the Ohio Val- ley friendly to the English, were taken to Aughwick, now Shirleysburg, where they were fed by the Colonial Author- ities of Pennsylvania. -

A-Brief-History-Of-The-Mohican-Nation

wig d r r ksc i i caln sr v a ar ; ny s' k , a u A Evict t:k A Mitfsorgo 4 oiwcan V 5to cLk rid;Mc-u n,5 3 ss l Y gew y » w a. 3 k lz x OWE u, 9g z ca , Z 1 9 A J i NEI x i c x Rat 44MMA Y t6 manY 1 YryS y Y s 4 INK S W6 a r sue`+ r1i 3 My personal thanks gc'lo thc, f'al ca ° iaag, t(")mcilal a r of the Stockbridge-IMtarasee historical C;orrunittee for their comments and suggestions to iatataraare tlac=laistcatic: aal aac c aracy of this brief' history of our people ta°a Raa la€' t "din as for her c<arefaal editing of this text to Jeff vcic.'of, the rlohican ?'yews, otar nation s newspaper 0 to Chad Miller c d tlac" Land Resource aM anaagenient Office for preparing the map Dorothy Davids, Chair Stockbridge -Munsee Historical Committee Tke Muk-con-oLke-ne- rfie People of the Waters that Are Never Still have a rich and illustrious history which has been retrained through oral tradition and the written word, Our many moves frorn the East to Wisconsin left Many Trails to retrace in search of our history. Maanv'rrails is air original design created and designed by Edwin Martin, a Mohican Indian, symbol- izing endurance, strength and hope. From a long suffering proud and deternuned people. e' aw rtaftv f h s is an aatathCutic basket painting by Stockbridge Mohican/ basket weavers. -

October 2008

1 Interstate Hiking Club Organized 1931 Affiliate of the NY-NJ Trail Conference Schedule of Hikes May 2008 through October 2008 Web Page: http:// www.MINDSPRING.COM/~INTERSTATEHIKING/ e-mail: [email protected] __________________________________________________________________________ Interstate Hiking Club C/O Charles Kientzler 711 Terhune Drive Wayne, NJ 07470-7111 First Class Mail 2 GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT THE INTERSTATE HIKING CLUB Who we are! The Interstate Hiking Club (IHC) is a medium-sized hiking club, organized in 1931. IHC has been affiliated with the NY/NJ Trail Conference, as a trail maintaining club, since 1931. Guests are welcome! An adult must accompany anyone under 18. No Pets allowed on IHC hikes. Where do we go? Most of our activities are centered in the NY/NJ area; some hikes, bicycle rides and canoe trips are farther away. The club occasionally sponsors trips in the Catskills and Pennsylvania. Our hikes are not usually accessible by public transportation. What do we do? Hikes, bicycle rides and canoe trips generally are scheduled for every Sunday, and some Fridays and Saturdays, as day-long outings. They are graded by difficulty of terrain, distance and pace. The Hiking grades are: Strenuous: More climbing, usually rugged walking, generally 9 miles or more. Moderate: Some climbing and rugged walking, but less than 9 miles. Easy: Generally easy, fairly level trails, slower pace, and 6 to 8 miles. The club also maintains trails in association with the NY/NJ Trail Conference. Two Sundays a year are devoted to this service work. In addition, in the past we have participated in the following: orienteering, snow-shoeing, cross-country skiing, swimming, canoeing, mountain biking, backpacking, and camp-outs in the Adirondacks and Maine. -

Here It Gradually Loses Elevation Approaching Lake Awosting

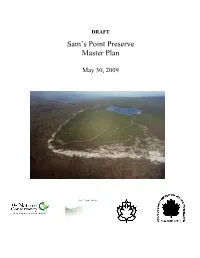

DRAFT Sam’s Point Preserve Master Plan May 30, 2009 Draft Master Plan Sam’s Point Preserve Cragsmoor, New York Prepared by: The Nature Conservancy Open Space Institute Sam’s Point Advisory Council Completed: (May 30, 2009) Contacts: Cara Lee, Shawangunk Ridge Program Director ([email protected] ) Heidi Wagner, Preserve Manager ([email protected] ) Gabriel Chapin, Forest and Fire Ecologist ([email protected] ) The Nature Conservancy Eastern New York Chapter Sam’s Point Preserve PO Box 86 Cragsmoor, NY 12420 Phone: 845-647-7989 or 845-255-9051 Fax: 845-255-9623 Paul Elconin ([email protected]) Open Space Institute 1350 Broadway, Suite 201 New York, NY 10018 Phone: 212-629-3981 Fax: 212-244-3441 ii Table of Contents Table of Contents ii List of Tables iii List of Figures and Maps iv List of Appendices v Acknowledgments vi Executive Summary vii Introduction A. The Northern Shawangunk Mountains 1 B. A Community Based Conservation Approach 4 C. History of Sam’s Point Preserve 4 D. Regional Context - Open Space Protection and Local Government 7 I. Natural Resource Information A. Geology and Soils 10 B. Vegetation and Natural Communities 11 C. Wildlife and Rare Species 15 II. Mission and Goals A. Mission Statement 18 B. Conservation Goals 19 C. Programmatic Goals 20 D. Land Protection Goals 20 III. Infrastructure A. Facilities Plan 26 B. Roads and Parking Areas 27 C. Trails 32 D. Signage, Kiosks and Access Points 35 E. Ice Caves Trail 36 iii IV. Ecological Management and Research A. Fire Management 38 B. Exotic and Invasive Species Control 42 C. -

Passaic County, New Jersey (All Jurisdictions)

VOLUME 1 OF 5 PASSAIC COUNTY, NEW JERSEY (ALL JURISDICTIONS) COMMUNITY NAME COMMUNITY NUMBER BLOOMINGDALE, BOROUGH OF 345284 CLIFTON, CITY OF 340398 HALEDON, BOROUGH OF 340399 HAWTHORNE, BOROUGH OF 340400 LITTLE FALLS, TOWNSHIP OF 340401 NORTH HALEDON, BOROUGH OF 340402 PASSAIC, CITY OF 340403 PATERSON, CITY OF 340404 POMPTON LAKES, BOROUGH OF 345528 PROSPECT PARK, BOROUGH OF 340406 RINGWOOD, BOROUGH OF 340407 TOTOWA, BOROUGH OF 340408 WANAQUE, BOROUGH OF 340409 WAYNE, TOWNSHIP OF 345327 WEST MILFORD, TOWNSHIP OF 340411 WOODLAND PARK, BOROUGH OF 340412 Preliminary: January 9, 2015 FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY NUMBER 34031CV001B Version Number 2.1.1.1 The Borough of Woodland Park was formerly known as the Borough of West Paterson. NOTICE TO FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY USERS Communities participating in the National Flood Insurance Program have established repositories of flood hazard data for floodplain management and flood insurance purposes. This Flood Insurance Study (FIS) may not contain all data available within the repository. It is advisable to contact the community repository for any additional data. Part or all of this FIS may be revised and republished at any time. In addition, part of this FIS may be revised by the Letter of Map Revision process, which does not involve republication or redistribution of the FIS. It is, therefore, the responsibility of the user to consult with community officials and to check the community repository to obtain the most current FIS components. Initial Countywide FIS Effective Date: September 28, 2007 Revised Countywide FIS Date: This preliminary FIS report does not include unrevised Floodway Data Tables or unrevised Flood Profiles. -

Army Corps of Engineers Response Document Draft

3.0 ORANGE COUNTY Orange County has experienced numerous water resource problems along the main stem and the associated tributaries of the Moodna Creek and the Ramapo River that are typically affected by flooding during heavy rain events over the past several years including streambank erosion, agradation, sedimentation, deposition, blockages, environmental degradation, water quality and especially flooding. However, since October 2005, the flooding issues have severely increased and flooding continues during storm events that may or may not be considered significant. Areas affected as a result of creek flows are documented in the attached trip reports (Appendix D). Throughout the Orange County watershed, site visits confirmed opportunities to stabilize the eroding or threatened banks restore the riparian habitat while controlling sediment transport and improving water quality, and balance the flow regime. If the local municipalities choose to request Federal involvement, there are several options, depending on their budget, desired timeframe and intended results. The most viable options include a specifically authorized watershed study or program, or an emergency streambank protection project (Section 14 of the Continuing Authorities Program), or pursing a Continuing Authorities Program study for Flood Risk Management or Aquatic Ecosystem Restoration (Section 205 and Section 206 of the Continuing Authorities Program, respectively). Limited Federal involvement could also be provided in the form of the Planning Assistance to States or Support for Others programs provide assistance and limited funds outside of traditional Corps authorities. A watershed study focusing on restoration of the Moodna Creek, Otter Creek, Ramapo River and their associated tributaries could address various problems using a systematic approach. -

Connecting with Nature Is Easier Than Ever Before with the New NYNJTC.Org

MAINTAINING 2,144 MILES OF TRAILS IN NY AND NJ NYNJTC.ORG WINTER 2017 TRAIL WALKER NEW YORK-NEW JERSEY TRAIL CONFERENCE • CONNECTING PEOPLE WITH NATURE SINCE 1920 VOLUNTEER AWARDS Connecting with Nature AARON STEVE Is Easier Than Ever Before with the New NYNJTC.org The New York-New Jersey everyone is encouraged to Celebrating Trail Conference is proud to share their thoughts on their announce the launch of the favorite spots with fellow hik- Extraordinary newly redesigned nynjtc.org ers at the bottom of each park, and the migration of our lega- hike, and destination page. Service to cy databases to a customer relationahip management Easy Tools to Give Back Local Trails (CRM) system fully integrat- ed with our website. The up- Because trails are built, main- The hard work and dedication dated website is the digital tained, and protected by the of Trail Conference volunteers version of walking through same outdoor-loving people is unparalleled. Yet their work the door at our Darlington who enjoy them, we’ve made goes unnoticed by the ma- Schoolhouse headquarters— finding opportunities to give jority of people who benefit all the information you need back as simple as finding a from their service—which, to prepare for your next ad- hike on the new nynjtc.org. when you think about it, isn’t venture on the trails is right at Through the Take Action pan- necessarily a bad thing. your fingertips. The website is el in the menu, discover ways When done right, with skill fully integrated with our new to volunteer, attend an event, and passion, trail construction CRM system to provide our accessibility using this power- to the most popular plac- learn about our programs, do- and maintenance—as well as members and volunteers a bet- ful tool as your guide. -

THE INDIANS of LENAPEHOKING (The Lenape Or Delaware Indians)

THE INDIANS OF LENAPEHOKING (The Lenape or Delaware Indians) By HERBERT C.KRAFT NCE JOHN T. KRAFT < fi Seventeenth Century Indian Bands in Lenapehoking tN SCALE: 0 2 5 W A P P I N Q E R • ' miles CONNECTICUT •"A. MINISS ININK fy -N " \ PROTO-MUNP R O T 0 - M U S E*fevj| ANDS; Kraft, Herbert rrcrcr The Tndians nf PENNSYLVANIA KRA hoking OKEHOCKING >l ^J? / / DELAWARE DEMCO NO . 32 •234 \ RINGVyOOP PUBLIC LIBRARY, NJ N7 3 6047 09045385 2 THE INDIANS OF LENAPEHOKING by HERBERT C. KRAFT and JOHN T. KRAFT ILLUSTRATIONS BY JOHN T. KRAFT 1985 Seton Hall University Museum South Orange, New Jersey 07079 145 SKYLAND3 ROAD RINGWOOD, NEW JERSEY 07456 THE INDIANS OF LENAPEHOKING: Copyright(c)1985 by Herbert C. Kraft and John T. Kraft, Archaeological Research Center, Seton Hall University Museum, South Orange, Mew Jersey. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book--neither text, maps, nor illustrations--may be reproduced in any way, including but not limited to photocopy, photograph, or other record without the prior agreement and written permission of the authors and publishers, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address Dr. Herbert C. Kraft, Archaeological Research Center, Seton Hall University Museum, South Orange, Mew Jersey, 07079 Library of Congress Catalog Number: 85-072237 ISBN: 0-935137-00-9 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The research, text, illustrations, and printing of this book were made possible by a generous Humanities Grant received from the New Jersey Department of Higher Education in 1984. -

LENAPE VILLAGES of DELAWARE COUNTY By: Chris Flook

LENAPE VILLAGES OF DELAWARE COUNTY By: Chris Flook After the signing of the Treaty of Greenville in 1795, many bands of Lenape (Delaware) Native Americans found themselves without a place to live. During the previous 200 years, the Lenape had been pushed west from their ancestral homelands in what we now call the Hudson and Delaware river valleys first into the Pennsylvania Colony in the mid1700s and then into the Ohio Country around the time of the American Revolution. After the Revolution, many Natives living in what the new American government quickly carved out to be the Northwest Territory, were alarmed of the growing encroachment from white settlers. In response, numerous Native groups across the territory formed the pantribal Western Confederacy in an attempt to block white settlement and to retain Native territory. The Western Confederacy consisted of warriors from approximately forty different tribes, although in many cases, an entire tribe wasn’t involved, demonstrating the complexity and decentralized nature of Native American political alliances at this time. Several war chiefs led the Western Confederacy’s military efforts including the Miami chief Mihšihkinaahkwa (Little Turtle), the Shawnee chief Weyapiersenwah (Blue Jacket), the Ottawa chief Egushawa, and the Lenape chief Buckongahelas. The Western Confederacy delivered a series of stunning victories over American forces in 1790 and 1791 including the defeat of Colonel Hardin’s forces at the Battle of Heller’s Corner on October 19, 1790; Hartshorn’s Defeat on the following day; and the Battle of Pumpkin Fields on October 21. On November 4 1791, the forces of the territorial governor General Arthur St. -

Book Reviews and Book Notes

BOOK REVIEWS AND BOOK NOTES EDITED BY RUSSELL J. FERGUSON University of Pittsburgh Thoinas Jefferson's Farm Book, with Conmmentary and Relevant Excerpts frons Other Writings. Edited by Edwin Morris Betts. (Published for the American Philosophical Society, by Princeton University Press, 1953. Pp. 506. $15.00.) In the new appraisal of American history that is occurring today-that of playing up the scientific-technological forces and playing down the politico- military-a volume such as the one before us assumes very special impor- tance. Here at long last we are able to sit down and read year by year (sometimes even day by day, and month by month) the Farm Book of the nation's most scientific farmer of the late 18th and early 19th century. The first entry was made in January, 1774; the last in May, 1826, a little more than a month before Jefferson died. One feels as he reads this Farmll Book that he is actually talking, walking, and riding with Jefferson as he lays out his plans each season for his farms around Monticello and nearby Poplar Forest. And what a wealth of information he gives us! We learn, for example, that as early as September, 1773, young Thomas (he was 30 years old) was "deeded" a number of slaves by his mother (his father Peter had died), and since, as the editor points out, "Slaves were the backbone of Jefferson's plantation," even this early entry is prophetic. It should be noted at the outset that Jefferson was always looking forward to the day when he could free his slaves, and help bring-about the complete abolition of slavery. -

Water Resources of the New Jersey Part of the Ramapo River Basin

Water Resources of the New Jersey Part of the Ramapo River Basin GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1974 Prepared in cooperation with the New Jersey Department of Conservation and Economic Development, Division of Water Policy and Supply Water Resources of the New Jersey Part of the Ramapo River Basin By JOHN VECCHIOLI and E. G. MILLER GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1974 Prepared in cooperation with the New Jersey Department of Conservation and Economic Development, Division of Water Policy and Supply UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1973 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 72-600358 For sale bv the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price $2.20 Stock Number 2401-02417 CONTENTS Page Abstract.................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction............................................................................................ ............ 2 Purpose and scope of report.............................................................. 2 Acknowledgments.......................................................................................... 3 Previous studies............................................................................................. 3 Geography...................................................................................................... 4 Geology -

Implications for the Calapooya Divide, Oregon

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Karen Joyce Starr for the degree of Master of Arts in Interdiscinlinary Studies in Anthr000loay. Geogranhv, and _Agricultural and Resource Economics presented on October 1, 1982 Title: THE CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE OF MOUNTAIN REGIONS; IMPLICATIONS FOR THE QALAPOOYA DIVIDE. OREGON Abstract approved: Redacted for Privacy Thomas C. Hogg Altitudinal variations in upland regions of the earthcreate variable climatic zones and conditions. Plant andanimal communities must adapt to these conditions, andwhen theyreach their tolerance limits for environmental conditions at the upper levels of a zone, they cease to exist inthe environment. Humans also utilize mountains for a variety of reasons. The cultural traits which result from the adaptationof groups of people to mountainenvironments are unique from those of the surrounding lowlanders. Adaptation to upland areas is most often expressed in a transhumant or agro-pastoral lifestyle attuned to the climatic variations and demands of the mountain environment. This distribution of cultural traits suggests thatmountains are considered unique culture areas, apart from but sharing sometraits in common with neighboring lowland areas. The Cultural Significance of Mountain Regions Implications for the Calapooya Divide, Oregon by Karen Joyce Starr A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies Completed October 1, 1982 Commencement June 1983 APPROVED: Redacted for Privacy Professor of Anthropology in charge of major Redacted for Privacy Chairman of Department of Anthropology Redacted for Privacy AssociateiDrofssor of Geography in charge of minor Redacted for Privacy Profe4or of Agricultural and Resource Economics in charge of minor Redacted for Privacy Dean of Graduat chool Date thesis is presented October 1.