Knowledge Reifying Force-Intention-Harm K(F+I+H): the Nature and Structure of Crime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Freedom, Sex & Power

W RECK: graduate journal of art history, visual art, and theory Volume 2, number 1 (2008) Freedom, Sex & Power:1 Film/Video Regulation in Ontario By Taryn Sirove, Ph.D. Candidate, Queen’s University P h o t o c o u r t e s y o f J o h n P o r t e r . Fig. 1. The Ontario Film and Video Appreciation Society (OFVAS) presenting its brief at public hearings on a new film classification law held at Queen’s Park, Toronto, Ontario, December 4-5, 1984. L-R: David Poole (CFMDC), Anna Gronau (The Funnel), Cyndra MacDowell (CARO). Photo by John Porter. “Ontario is getting out of the film censorship business,” announced the headline of the December 10, 2004 Toronto Star.2 This, after Glad Day Bookshop, a small retailer specializing in queer literature and videotapes, won a decisive legal battle against the Ontario Film Review Board (OFRB).3 Glad Day Bookshop appealed its previous conviction for illegally distributing the sexually-explicit video, Descent, by “renowned” American filmmaker, Steven Scarborough.4 The bookshop called upon the federal Charter of Rights and Freedoms to overturn a provincial regulation—the Theatres Act—which required that all videos and films be either approved by the OFRB, be partially censored, or altogether banned. Despite Glad Day Bookshop’s successful legal challenge to the Act and the OFRB, the Star headline was totally erroneous; as of today, the OFRB has retained its powers for the prior restraint and banning of film and video in Ontario. In this essay, I map a number of interventions and contests around the regulation of video and film from the 1980s until the present. -

Vancouver by Tina Gianoulis

Vancouver by Tina Gianoulis Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2006 glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Cosmopolitan Vancouver, nestled on Canada's west coast in a picturesque triangle between English Bay, Burrard Inlet, and the Fraser River, has developed in less than 200 years from a frontier outpost in an untamed land to one of the fastest-growing cities in North America. With a constant influx of immigrants and a vigorous and adaptable economy, Vancouver is a progressive city with a large and active queer community. That community began organizing in the 1960s, with the founding of Canada's first homophile organization, and has continued into the 2000s, as activists work to protect queer rights and develop queer culture. With its sheltered location, fertile farmland, and rich inland waterways, the southwestern corner of British Columbia's mainland attracted settlers from a variety of native cultures for over three thousand years. More than twenty tribes, including the Tsawwassen and Musqueam, comprised the Stó:lo Nation, the "People of the Water," who farmed and fished the Fraser River Valley before the arrival of European explorers in the late eighteenth century. From the first European trading post, established by the Hudson Bay Company in 1827, the small community soon grew into a boomtown with a thriving economy based on its lumber and mining industries, fisheries, and agriculture. By the late 1800s, the settlement had become a hub for a newly developing railroad network, and in 1886, the City of Vancouver was incorporated. The city grew rapidly, tripling its population within a few decades and spawning a construction boom in the early 1900s. -

Habermas, Legal Legitimacy, and Creative Cost Awards in Recent Canadian Jurisprudence

Dalhousie Law Journal Volume 30 Issue 1 Article 5 4-1-2007 Habermas, Legal Legitimacy, and Creative Cost Awards in Recent Canadian Jurisprudence Michael Fenrick Dalhousie University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.schulichlaw.dal.ca/dlj Part of the Courts Commons Recommended Citation Michael Fenrick, "Habermas, Legal Legitimacy, and Creative Cost Awards in Recent Canadian Jurisprudence" (2007) 30:1 Dal LJ 165. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Schulich Law Scholars. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dalhousie Law Journal by an authorized editor of Schulich Law Scholars. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Michael Fenrick* Habermas, Legal Legitimacy, and Creative Cost Awards in Recent Canadian Jurisprudence- Access to justice continues to be a live issue in Canadian courtrooms. While state-sponsored initiatives that promote access continue to flounder in Canada or in some cases, are cancelled altogether, the pressure is mounting to find creative solutions that facilitate greater participation in formal dispute resolution processes. The price of failing in this regard is very high. To truly flourish, both social cohesion and individual liberties require a more participatory and inclusive legal system than the one that currently precludes all but the wealthiest from accessing our courts. Drawing on the legal philosophy of Jargen Habermas, the author examines access problems from the perspective of the civil litigant who is facing the unmanageable financial burden of having her legal rights recognized and adjudicated in a Canadian courtroom. Specifically, this paper considers the role which creative costs orders can play in advancing the goal of fuller legal participation. -

Brian Lam's Speech for Little Sisters 2014 Gray Campbell Award

Gray Campbell Award presenter’s speech by Brian Lam for recipients Jim Deva & Janine Fuller, Little Sister’s Book & Art Emporium, 2014 In 1984, a young man of twenty-two moved to the big city of Vancouver for a summer job. Being shy and somewhat aloof, he didn’t make new friends easily, and while he loved the company of a good novel, he wasn’t able to find many books that told the kinds of stories in which he saw himself, making him feel less alone. But then he stumbled upon a bookstore located on the second floor of a converted house on Thurlow Street in the West End. Ascending the staircase, he saw announcements of meetings for various gay and lesbian groups, and typewritten notices from those looking for “like-minded” roommates, and handwritten posters asking for witnesses to the latest gay bashing down the street. And then once upstairs, in the narrow confines of crowded bookshelves, and in the covers of so many books of gay fiction, poetry, self-help, and history, he saw a reflection of himself looking back at him, and he finally felt like he had found a second home of sorts. That young man was me, and that bookstore was Little Sister’s. A year earlier in 1983, Jim Deva and Bruce Smyth, along with Barb Thomas, opened Little Sister’s Book and Art Emporium in that converted house on Thurlow Street. After moving to Vancouver from the prairies, Jim and Bruce worked in retail, and when they decided to go into business for themselves, they considered opening a clothing store or a shoe store, but finally settled on the idea of selling gay and lesbian art and books. -

Challenged Books and Magazines List Updated February 2012 2011

Challenged Books and Magazines List Updated February 2012 This selective list provides information on numerous books and some magazines and newspapers that have been challenged in the past decades. Each challenge sought to limit public access to these publications in schools, libraries and elsewhere. Some challenges were upheld; others were rejected. We have tried to update our research on unresolved challenges. Because some challenges are dismissed, the publications remain on library shelves or curriculum lists. We think it is worthwhile to include such instances because the effect of a controversy over publications can spread even though the would-be banners lose. A book or magazine with a controversial reputation can be quietly dropped from reading lists and curricula. This interference can be most insidious—quiet acquiescence to the scare tactics that would-be censors know how to employ. Because organizations and community groups that ask for book and magazine bans usually want to avoid public controversies, it is often difficult to discover why challenges are launched or what becomes of them. If you know of book or magazine or newspaper challenges or, better still, satisfactory resolutions anywhere in Canada, please use the accompanying case study form to give us details. 2011 Brunetti, Ivan, Lilli Carré, et al. Black Eye 1: Graphic Transmissions to Cause Ocular Hypertension. 2011—Officials of the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) seized five copies of this comic book anthology in Buffalo, New York, while artist Tom Neely and a colleague were travelling to the Toronto Comic Arts Festival. Objection—The customs officers found images of sex and violence in the book. -

Preserving Lesbian Oral History in Canada* ELISE CHENIER

Hidden from Historians: Preserving Lesbian Oral History in Canada* ELISE CHENIER RÉSUMÉ L’histoire lesbienne est une partie importante du passé canadien, mais certains documents de recherche les plus utiles sont en danger de disparition. Au cours des vingt dernières années, les activistes canadiens et les chercheurs ont mené des interviews d’histoire orale avec des lesbiennes au Canada. Cependant, seulement quel ques-uns ont fait don de leur recherche à un centre d’archives. À partir des résultats obtenus dans un sondage auprès des spécialistes en histoire orale, cet article montre qu’un manque de formation, une pénurie de ressources financières et une incapacité de mettre en place un plan pour faire don des documents de recherche à un centre d’archives sont trois obstacles importants qui empêchent la préservation de l’histoire orale lesbienne. L’article décrit aussi les Archive of Lesbian Oral History, des archives numériques internationales fondées par l’auteure. ABSTRACT Lesbian history is an important part of Canada’s past but some of the most valuable research material we have is in danger of disappearing. Over the past twenty years Canadian activists and researchers have conducted many oral history interviews with lesbians in Canada, yet only a handful have donated their research material to an archive. Drawing on the findings of a research questionnaire distributed to oral historians, this article shows that a lack of training, an absence of financial resources, and a failure to put in place a plan to donate research material to an archive are three of the most important barriers to preserving lesbian oral history in Canada. -

Challenged Books List 1 of 21

Freedom to Read Kit 2004 — Challenged Books List 1 of 21 Challenged Books List This selective list provides information on more than 100 books that have been challenged in the past 21 years. Each challenge sought to limit public access to the books in schools, libraries, or bookstores. Some challenges were upheld; others were rejected. We have tried to update our research on unresolved challenges. Because some challenges are dismissed, the books remain on library shelves or curriculum lists. We think it worthwhile to include such instances because the effect of a controversy over print material can spread, even though the would-be book-banners lose. A book with a controversial reputation tends to be quietly dropped from reading lists and curricula. This interference can be most insidious—quiet acquiescence to the kind of scare tactics that would-be censors know how to employ. Because organizations and community groups that ask for book and magazine bans generally want to avoid public controversies, it is often difficult to discover why challenges are launched or what becomes of them. If you know of book challenges or, better still, satisfactory resolutions anywhere in Canada, please use the accompanying case study form to give us details. Challenged Books Alma, Ann. Something to Tell. 2000—At the beginning of a Children’s Book Week tour of schools and libraries in Prince Edward Island, the author was told that she should not read from this book, one of her three titles for young readers. Cause of objection—The tour coordinator said P.E.I. students were not mature enough for the book, which tells the story of a girl who has been subjected to sexual touching by the headmistress of her school. -

An Oral History of Everywomans Books in Victoria, BC, 1975-1997

Books By Women, For Women, About Women: An Oral History of Everywomans Books in Victoria, B.C., 1975-1997 by Taylor Antoniazzi B.A., University of Victoria, 2013 M.A., University of Waterloo, 2016 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History ©Taylor Antoniazzi, 2020 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. Books By Women, For Women, About Women: An Oral History of Everywomans Books in Victoria, B.C., 1975-1997 by Taylor Antoniazzi B.A., University of Victoria, 2013 M.A., University of Waterloo, 2016 Supervisory Committee Dr. Lynne Marks, Supervisor Department of History Dr. Annalee Lepp, Departmental Member Department of Gender Studies ii Abstract Everywomans Books was a non-profit feminist bookstore established in Victoria, B.C. in 1975. The store closed in 1997 due to financial problems, but it was the last remaining non-profit feminist bookstore run by an all-volunteer collective in Canada. From the beginning, the collective pursued its vision to create a comfortable, safe space for women to access vital information that was hard to find anywhere else. Though creating and maintaining the bookstore was a thoroughly feminist endeavour, the bookstore itself was not a centre of political activity in the community. Its animus was to provide the literature that would raise women’s consciousness, impel their identity formation, foster bold, independent thinking and jolt women into political action. -

Customs, Censorship and the Charter: the Little Sisters Case

TSpace Research Repository tspace.library.utoronto.ca Customs, Censorship and the Charter: The Little Sisters Case Brenda Cossman and Bruce Ryder Version Published PDF Citation Brenda Cossman & Bruce Ryder, "Customs, Censorship and the (published version) Charter: The Little Sisters Case" (1996) 7:4 Constitutional Forum 103. Publisher’s Statement Brenda Cossman & Bruce Ryder, "Customs, Censorship and the Charter: The Little Sisters Case" (1996) 7:4 Constitutional Forum 103. © [1996]. The final version of this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.21991/c9k37x How to cite TSpace items Always cite the published version, so the author(s) will receive recognition through services that track citation counts, e.g. Scopus. If you need to cite the page number of the author manuscript from TSpace because you cannot access the published version, then cite the TSpace version in addition to the published version using the permanent URI (handle) found on the record page. This article was made openly accessible by U of T Faculty. Please tell us how this access benefits you. Your story matters. CUST'OMS CENSORSHIP AND THE CHARTER: THE LITtLE SISTERS CASE Brenda·.Cossman and Bruce Ryder INTRODUCTION Little Sisters Book and Art Emporium is Sisters and Customs by affirming the importance to Vancouver's only bookstore specializing in gay and the life of the nation of both homosexual literature lesbian literature; it also has served as a focus of and the existing legislative regime of border censor social and political activities of the local gay and ship. lesbian communities since its inception in 1983. Canada Customs is the arm ofthe federal government It took Justice Smith a full thirteen months to empowered to prohibit the entry of obscene imported ponder the evidence presented at trial and to prepare publications into the country, a power originally his decision. -

Censor, Resist, Repeat: a History of Censorship of Gay and Lesbian Sexual Representation in Canada

Cossman Proof 1 (Do Not Delete) 2/18/2014 11:25 AM Censor, Resist, Repeat: A History of Censorship of Gay and Lesbian Sexual Representation in Canada BRENDA COSSMAN* I. INTRODUCTION Canada has a long and illustrious history of censorship. Since 1867, it would seem that a defining characteristic of Canadian national identity has been to censor, particularly at our borders, to make sure that material that would “deprave and corrupt” was not permitted entry into our country. The censorship of gay and lesbian1 materials is of a slightly more recent vintage, largely paralleling the rise of the gay and lesbian liberation movement in the 1970s. This is not to say that gay and lesbian themed material was not censored before the 1970s. It was. But the heyday of gay and lesbian censorship follows the emergence of the gay and lesbian liberation movement in the 1970s and 1980s. In this essay, I review this history of censorship, focusing on both customs censorship and criminal obscenity prosecutions. I argue that despite many legal defeats, the censorship of gay and lesbian sexual representations in Canada failed; indeed it failed precisely by its own internal contradictory nature. Censorship controversies, I argue, represent a site of public contestation over legitimate and illegitimate speech, and more specifically, that censorship controversies over sexual speech represent a contestation over sexual normativity. Relying on the new censorship studies literature, I argue that each moment of censorship mobilized resistance, making the story of censorship one of resistance and of redrawing the borders of legitimate sexual speech. By the 2000s, gay and lesbian sexual representations had crossed those borders, and their non-heterosexuality alone was no longer sufficient to cast them as non- normative and censorable. -

Mapping Lesbian and Bisexual Women's Erotic Agency and Identity

Worried About the Misfiring: Mapping Lesbian and Bisexual Women’s Erotic Agency and Identity Under Canadian Obscenity Laws by Morghan Watson Supervised by Dr. Rachel Hope Cleves A Graduating Essay Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements, in the Honours Programme. For the Degree of Bachelor of Arts In the Department Of History The University of Victoria April 3, 2018 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents. .1 Acknowledgements. .. .2 Introduction. .. .3 Literature Review A History of Homophobia and Sex Criminalization The Feminist ‘Sex Wars’ Section One: The Butler Decision. .13 Linking Radical Feminism to the Butler Decision R. v. Butler (1992) Section Two: Glad Day Bookstore - A Case of Bad Attitude. 19 R v. Scythes (1993) Reading Sadomasochism: Consent in a Post-Butler Canada Section Three: Little Sister’s Book and Art Emporium - Identity and Erotica. .29 Little Sister’s Book and Art Emporium v. Canada (1996 & 2000) The Importance of Erotica in Identity and Community Conclusion. .41 References. 43 Academic Sources Legal Sources 2 Acknowledgements I would first and foremost like to acknowledge that the learning and research I have done at the University of Victoria has occured on the traditional, unceded territories of the Lekwungen-speaking peoples. I also wish to acknowledge the Songhees, Esquimalt and WSÁNEĆ peoples who have an historical and ongoing relationship with this territory, which has been drastically shaped by continued colonial occupation, which I participate in, and benefit from. I owe many thanks to Dr. Rachel Cleves, who donated her time and energy to mentor me through this project. I found reading the material for my thesis both important and challenging, and I am grateful to have studied it under Dr. -

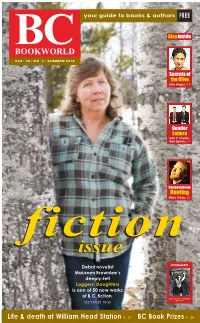

Summer 2014 Volume 28

your guide to books & authors FREE BC Also inside BOOKWORLD VOL. 28 • NO. 2 • SUMMER 2014 Secrets of the Olive Julie Angus, P.5 Gender Failure Ivan E. Coyote, Rae Spoon, P.7 Compassionate Hunting Miles Olson, P.9 fictionfiction issueissue Debut novelist DOGGED Maureen Brownlee’s deeply-felt Loggers’ Daughters is one of 50 new works PHOTO KEIL of B.C. fiction. PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40010086 SEE PAGES 13-33 LAURA Life & death at William Head Station P. 11 • BC Book Prizes P. 20 2 BC BOOKWORLD SUMMER 2014 NEWS BCTOP* SELLERS The Market Gardener (New Society Publishers $24.95) by Jean-Martin Fortier • A Timeless Place: The Ontario Cottage (UBC Press $32.95) by Julia Harrison • Allen Carr’s Easy Way to Stop Smoking (Sandhill Book Marketing $19.95) by Allen Carr • This Day in Vancouver (Anvil Press $38) by Jesse Donaldson SUN VANCOUVER / REEFER MADNESS PHOTO PERRIN IS GOVERNMENTAL WARD EN YEARS AGO, CANADA’S PUBLIC SAFETY Marijuana plants marijuana grow ops that challenges claims made by the RCMP in East Vancouver, minister Anne McLellan an and media regarding organized crime, violence and public safety. from Killer Weed: That justice department report is corroborated by scholarly nounced that the federal government was Marijuana Grow Ops, research — but the justice department study was never re- T Media and Justice committed to eradi-cating marijuana growing op- leased. Boyd and Carter obtained a copy of the unreleased study from a reporter who received it following a Freedom of Infor- erations and that people who smoke marijuana are stupid. mation request.