Backfires: White, Black and Grey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart Is to Be Used As a Guide Only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** Green Beige Purple V

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart is to be used as a guide only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** RAL 1000 Green Beige RAL 4007 Purple Violet RAL 7008 Khaki Grey RAL 4008 RAL 7009 RAL 1001 Beige Signal Violet Green Grey Tarpaulin RAL 1002 Sand Yellow RAL 4009 Pastel Violet RAL 7010 Grey RAL 1003 Signal Yellow RAL 5000 Violet Blue RAL 7011 Iron Grey RAL 1004 Golden Yellow RAL 5001 Green Blue RAL 7012 Basalt Grey Ultramarine RAL 1005 Honey Yellow RAL 5002 RAL 7013 Brown Grey Blue RAL 1006 Maize Yellow RAL 5003 Saphire Blue RAL 7015 Slate Grey Anthracite RAL 1007 Chrome Yellow RAL 5004 Black Blue RAL 7016 Grey RAL 1011 Brown Beige RAL 5005 Signal Blue RAL 7021 Black Grey RAL 1012 Lemon Yellow RAL 5007 Brillant Blue RAL 7022 Umbra Grey Concrete RAL 1013 Oyster White RAL 5008 Grey Blue RAL 7023 Grey Graphite RAL 1014 Ivory RAL 5009 Azure Blue RAL 7024 Grey Granite RAL 1015 Light Ivory RAL 5010 Gentian Blue RAL 7026 Grey RAL 1016 Sulfer Yellow RAL 5011 Steel Blue RAL 7030 Stone Grey RAL 1017 Saffron Yellow RAL 5012 Light Blue RAL 7031 Blue Grey RAL 1018 Zinc Yellow RAL 5013 Cobolt Blue RAL 7032 Pebble Grey Cement RAL 1019 Grey Beige RAL 5014 Pigieon Blue RAL 7033 Grey RAL 1020 Olive Yellow RAL 5015 Sky Blue RAL 7034 Yellow Grey RAL 1021 Rape Yellow RAL 5017 Traffic Blue RAL 7035 Light Grey Platinum RAL 1023 Traffic Yellow RAL 5018 Turquiose Blue RAL 7036 Grey RAL 1024 Ochre Yellow RAL 5019 Capri Blue RAL 7037 Dusty Grey RAL 1027 Curry RAL 5020 Ocean Blue RAL 7038 Agate Grey RAL 1028 Melon Yellow RAL 5021 Water Blue RAL 7039 Quartz Grey -

The Ethics of Intelligence Collection Ross W. Bellaby

What’s the Harm? The Ethics of Intelligence Collection Ross W. Bellaby Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Department of International Politics Aberystwyth University June 13th, 2011 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed ...................................................................... (Ross W. Bellaby) Date ........................................................................ STATEMENT 1 This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Where *correction services have been used, the extent and nature of the correction is clearly marked in a footnote(s). Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed ..................................................................... (Ross W. Bellaby) Date ........................................................................ [*this refers to the extent to which the text has been corrected by others] STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ..................................................................... (Ross W. Bellaby) Date ........................................................................ I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying -

Green, Grey Or Green-Grey? Decoding Infrastructure Integration and Implementation for Residential Street Retrofits

Lincoln University Digital Thesis Copyright Statement The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: you will use the copy only for the purposes of research or private study you will recognise the author's right to be identified as the author of the thesis and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate you will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from the thesis. Green, Grey or Green-Grey? Decoding infrastructure integration and implementation for residential street retrofits. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Landscape Architecture at L I N C O L N U N I V E R S I T Y New Zealand by K S E N I A I. A L E K S A N D R O V A Lincoln University 2016 A B S T R A C T New-world countries are often characterized by large areas of sprawling post-war suburban development. The streets of these suburbs are often criticized for being unattractive transport corridors that prioritize cars at the cost of the pedestrian environment and ecological health of their neighbourhoods. Green infrastructure (LID) street retrofits, as well as grey infrastructure-dominated traffic calming schemes have been used as partial solutions to the adverse effects of post-war street design. There is, however, a lack of implementation of these measures, along with some confusion as to what is defined as green and grey infrastructure at the street scale. -

Coming to Grips with Life in the Disinformation Age

Coming to Grips with Life in the Disinformation Age “The Information Age” is the term given to post-World War II contemporary society, particularly from the Sixties, onward, when we were coming to the realization that our ability to publish information of all kinds, fact and fiction, was increasing at an exponential rate so as to make librarians worry that they would soon run out of storage space. Their storage worries were temporarily allayed by the advent of the common use of microform analog photography of printed materials, and eventually further by digital technology and nanotechnology. It is noted that in this era, similar to other past eras of great growth in communications technology such as written language, the printing press, analog recording, and telecommunication, dramatic changes occurred as well in human thinking and socialness. More ready archiving negatively impacted our disposition to remember things by rote, including, in recent times, our own phone numbers. Moreover, many opportunities for routine socializing were lost, particularly those involving public speech and readings, live music and theater, live visits to neighbors and friends, etc. The recognition that there had been a significant tradeoff from which there seemed to be no turning back evoked discussion of how to come to grips with “life in the Information Age”. Perhaps we could discover new social and intellectual opportunities from our technological advances to replace the old ones lost, ways made available by new technology. Today we are facing a new challenge, also brought on largely by new technology: that of coming to grips with life in the “Disinformation Age”. -

Cryptography

Cryptography From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search "Secret code" redirects here. For the Aya Kamiki album, see Secret Code. German Lorenz cipher machine, used in World War II to encrypt very-high-level general staff messages Cryptography (or cryptology; from Greek κρυπτός, kryptos, "hidden, secret"; and γράφ, gráph, "writing", or -λογία, -logia, respectively)[1] is the practice and study of hiding information. Modern cryptography intersects the disciplines of mathematics, computer science, and engineering. Applications of cryptography include ATM cards, computer passwords, and electronic commerce. Cryptology prior to the modern age was almost synonymous with encryption, the conversion of information from a readable state to nonsense. The sender retained the ability to decrypt the information and therefore avoid unwanted persons being able to read it. Since WWI and the advent of the computer, the methods used to carry out cryptology have become increasingly complex and its application more widespread. Alongside the advancement in cryptology-related technology, the practice has raised a number of legal issues, some of which remain unresolved. Contents [hide] • 1 Terminology • 2 History of cryptography and cryptanalysis o 2.1 Classic cryptography o 2.2 The computer era • 3 Modern cryptography o 3.1 Symmetric-key cryptography o 3.2 Public-key cryptography o 3.3 Cryptanalysis o 3.4 Cryptographic primitives o 3.5 Cryptosystems • 4 Legal issues o 4.1 Prohibitions o 4.2 Export controls o 4.3 NSA involvement o 4.4 Digital rights management • 5 See also • 6 References • 7 Further reading • 8 External links [edit] Terminology Until modern times cryptography referred almost exclusively to encryption, which is the process of converting ordinary information (plaintext) into unintelligible gibberish (i.e., ciphertext).[2] Decryption is the reverse, in other words, moving from the unintelligible ciphertext back to plaintext. -

148 Colour Chart

148 colour chart IVORY PRIMROSE BUTTERCUP SOFT LIME TULIP YELLOW LEMON YELLOW CANARY SUNFLOWER ALMOND BLUSH SAFFRON Y418 Y919 Y417 Y828 Y337 Y747 Y657 Y367 Y156 O819 O729 O739 VANILLA PASTEL YELLOW MUSTARD OATMEAL APRICOT HONEYCOMB GOLD AMBER PUMPKIN GINGER BRIGHT ORANGE MANDARIN O929 O949 O948 O628 O538 O547 O555 O567 O467 O136 O177 O277 ORANGE SPICE BURNT ORANGE SATIN DUSKY PINK PUTTY SUNKISSED PINK CORAL SOFT PEACH PEACH MANGO PASTEL PINK R866 O346 R946 Y129 O518 O618 O228 R937 O138 O148 O248 R738 COCKTAIL PINK SALMON PINK ANTIQUE PINK LIPSTICK RED RED BERRY RED RUBY POPPY CRIMSON CARDINAL RED BURGUNDY MAROON R438 R547 R346 R576 R666 R665 R455 R565 R445 R244 R424 M544 PALE PINK BABY PINK ROSE PINK CERISE HOT PINK MAGENTA CARMINE DUSKY ROSE BLOSSOM PINK CARNATION FUCHSIA PINK SLATE R519 R228 M727 M647 R365 M865 R156 R327 M428 M328 M137 V715 AMETHYST PURPLE MULBERRY PLUM AUBERGINE LAVENDER ORCHID LILAC BLUEBELL VIOLET PRUSSIAN BLUE PEARL V626 V546 V865 V735 V524 V518 V528 V327 V127 V245 V464 B528 CORNFLOWER COBALT BLUE CHINA BLUE MIDNIGHT BLUE INDIGO BLUE ROYAL BLUE TRUE BLUE AZURE SKY BLUE CYAN PASTEL BLUE POWDER BLUE B617 B637 B736 B624 V234 V264 B555 B346 B137 C847 C719 B119 ARCTIC BLUE DENIM BLUE AEGEAN FRENCH NAVY COOL AQUA DUCK EGG TURQUOISE MARINE PETROL BLUE HOLLY PINE EMERALD B138 C917 B146 B445 C429 C528 C247 C446 C824 G724 G635 G657 GREEN LUSH GREEN PASTEL GREEN SOFT GREEN MINT GREEN GRASS FOREST GREEN TEA GREEN GREY GREEN MEADOW GREEN APPLE LEAF GREEN G847 G756 G829 G817 G637 G457 G356 G619 G917 G339 G338 G258 BRIGHT GREEN -

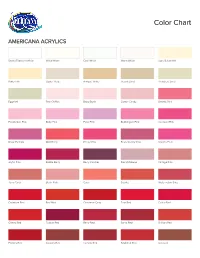

Color Chart Colorchart

Color Chart AMERICANA ACRYLICS Snow (Titanium) White White Wash Cool White Warm White Light Buttermilk Buttermilk Oyster Beige Antique White Desert Sand Bleached Sand Eggshell Pink Chiffon Baby Blush Cotton Candy Electric Pink Poodleskirt Pink Baby Pink Petal Pink Bubblegum Pink Carousel Pink Royal Fuchsia Wild Berry Peony Pink Boysenberry Pink Dragon Fruit Joyful Pink Razzle Berry Berry Cobbler French Mauve Vintage Pink Terra Coral Blush Pink Coral Scarlet Watermelon Slice Cadmium Red Red Alert Cinnamon Drop True Red Calico Red Cherry Red Tuscan Red Berry Red Santa Red Brilliant Red Primary Red Country Red Tomato Red Naphthol Red Oxblood Burgundy Wine Heritage Brick Alizarin Crimson Deep Burgundy Napa Red Rookwood Red Antique Maroon Mulberry Cranberry Wine Natural Buff Sugared Peach White Peach Warm Beige Coral Cloud Cactus Flower Melon Coral Blush Bright Salmon Peaches 'n Cream Coral Shell Tangerine Bright Orange Jack-O'-Lantern Orange Spiced Pumpkin Tangelo Orange Orange Flame Canyon Orange Warm Sunset Cadmium Orange Dried Clay Persimmon Burnt Orange Georgia Clay Banana Cream Sand Pineapple Sunny Day Lemon Yellow Summer Squash Bright Yellow Cadmium Yellow Yellow Light Golden Yellow Primary Yellow Saffron Yellow Moon Yellow Marigold Golden Straw Yellow Ochre Camel True Ochre Antique Gold Antique Gold Deep Citron Green Margarita Chartreuse Yellow Olive Green Yellow Green Matcha Green Wasabi Green Celery Shoot Antique Green Light Sage Light Lime Pistachio Mint Irish Moss Sweet Mint Sage Mint Mint Julep Green Jadeite Glass Green Tree Jade -

S:\FULLCO~1\HEARIN~1\Committee Print 2018\Henry\Jan. 9 Report

Embargoed for Media Publication / Coverage until 6:00AM EST Wednesday, January 10. 1 115TH CONGRESS " ! S. PRT. 2d Session COMMITTEE PRINT 115–21 PUTIN’S ASYMMETRIC ASSAULT ON DEMOCRACY IN RUSSIA AND EUROPE: IMPLICATIONS FOR U.S. NATIONAL SECURITY A MINORITY STAFF REPORT PREPARED FOR THE USE OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JANUARY 10, 2018 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Relations Available via World Wide Web: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/index.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 28–110 PDF WASHINGTON : 2018 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Mar 15 2010 04:06 Jan 09, 2018 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5012 Sfmt 5012 S:\FULL COMMITTEE\HEARING FILES\COMMITTEE PRINT 2018\HENRY\JAN. 9 REPORT FOREI-42327 with DISTILLER seneagle Embargoed for Media Publication / Coverage until 6:00AM EST Wednesday, January 10. COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS BOB CORKER, Tennessee, Chairman JAMES E. RISCH, Idaho BENJAMIN L. CARDIN, Maryland MARCO RUBIO, Florida ROBERT MENENDEZ, New Jersey RON JOHNSON, Wisconsin JEANNE SHAHEEN, New Hampshire JEFF FLAKE, Arizona CHRISTOPHER A. COONS, Delaware CORY GARDNER, Colorado TOM UDALL, New Mexico TODD YOUNG, Indiana CHRISTOPHER MURPHY, Connecticut JOHN BARRASSO, Wyoming TIM KAINE, Virginia JOHNNY ISAKSON, Georgia EDWARD J. MARKEY, Massachusetts ROB PORTMAN, Ohio JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon RAND PAUL, Kentucky CORY A. BOOKER, New Jersey TODD WOMACK, Staff Director JESSICA LEWIS, Democratic Staff Director JOHN DUTTON, Chief Clerk (II) VerDate Mar 15 2010 04:06 Jan 09, 2018 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 S:\FULL COMMITTEE\HEARING FILES\COMMITTEE PRINT 2018\HENRY\JAN. -

The Glamorization of Espionage in the International Spy Museum

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2015 Counter to Intelligence: The Glamorization of Espionage in the International Spy Museum Melanie R. Wiggins College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the American Film Studies Commons, American Material Culture Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, Other American Studies Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Wiggins, Melanie R., "Counter to Intelligence: The Glamorization of Espionage in the International Spy Museum" (2015). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 133. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/133 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Counter to Intelligence: The Glamorization of Espionage in the International Spy Museum A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in American Studies from The College of William and Mary by Melanie Rose Wiggins Accepted for____________________________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) _________________________________________________________ Alan Braddock, Director _________________________________________________________ Charlie McGovern _________________________________________________________ -

International Spy Museum

International Spy Museum Searchable Master Script, includes all sections and areas Area Location, ID, Description Labels, captions, and other explanatory text Area 1 – Museum Lobby M1.0.0.0 ΚΑΤΆΣΚΟΠΟΣ SPY SPION SPIJUN İSPİYON SZPIEG SPIA SPION ESPION ESPÍA ШПИОН Language of Espionage, printed on SCHPION MAJASUSI windows around entrance doors P1.1.0.0 Visitor Mission Statement For Your Eyes Only For Your Eyes Only Entry beyond this point is on a need-to-know basis. Who needs to know? All who would understand the world. All who would glimpse the unseen hands that touch our lives. You will learn the secrets of tradecraft – the tools and techniques that influence battles and sway governments. You will uncover extraordinary stories hidden behind the headlines. You will meet men and women living by their wits, lurking in the shadows of world affairs. More important, however, are the people you will not meet. The most successful spies are the unknown spies who remain undetected. Our task is to judge their craft, not their politics – their skill, not their loyalty. Our mission is to understand these daring professionals and their fallen comrades, to recognize their ingenuity and imagination. Our goal is to see past their maze of mirrors and deception to understand their world of intrigue. Intelligence facts written on glass How old is spying? First record of spying: 1800 BC, clay tablet from Hammurabi regarding his spies. panel on left side of lobby First manual on spy tactics written: Over 2,000 years ago, Sun Tzu’s The Art of War. 6 video screens behind glass panel with facts and images. -

Flags and Symbols � � � Gilbert Baker Designed the Rainbow flag for the 1978 San Francisco’S Gay Freedom Celebration

Flags and Symbols ! ! ! Gilbert Baker designed the rainbow flag for the 1978 San Francisco’s Gay Freedom Celebration. In the original eight-color version, pink stood for sexuality, red for life, orange for healing, yellow for the sun, green for nature, turquoise for art, indigo for harmony and violet for the soul.! " Rainbow Flag First unveiled on 12/5/98 the bisexual pride flag was designed by Michael Page. This rectangular flag consists of a broad magenta stripe at the top (representing same-gender attraction,) a broad stripe in blue at the bottoms (representing opposite- gender attractions), and a narrower deep lavender " band occupying the central fifth (which represents Bisexual Flag attraction toward both genders). The pansexual pride flag holds the colors pink, yellow and blue. The pink band symbolizes women, the blue men, and the yellow those of a non-binary gender, such as a gender bigender or gender fluid Pansexual Flag In August, 2010, after a process of getting the word out beyond the Asexual Visibility and Education Network (AVEN) and to non-English speaking areas, a flag was chosen following a vote. The black stripe represents asexuality, the grey stripe the grey-are between sexual and asexual, the white " stripe sexuality, and the purple stripe community. Asexual Flag The Transgender Pride flag was designed by Monica Helms. It was first shown at a pride parade in Phoenix, Arizona, USA in 2000. The flag represents the transgender community and consists of five horizontal stripes. Two light blue which is the traditional color for baby boys, two pink " for girls, with a white stripe in the center for those Transgender Flag who are transitioning, who feel they have a neutral gender or no gender, and those who are intersex. -

Propaganda As Communication Strategy: Historic and Contemporary Perspective

Academy of Marketing Studies Journal Volume 24, Issue 4, 2020 PROPAGANDA AS COMMUNICATION STRATEGY: HISTORIC AND CONTEMPORARY PERSPECTIVE Mohit Malhan, FPM Scholar, Indian Institute of Management, Lucknow Dr. Prem Prakash Dewani, Associate Professor, Indian Institute of Management, Lucknow ABSTRACT In a world entrapped in their own homes during the Covid-19 crisis, digital communication has taken a centre stage in most people’s lives. Where before the pandemic we were facing a barrage of fake news, the digitally entrenched pandemic world has deeply exacerbated the problem. The purpose of choosing this topic is that the topic is new and challenging. In today’s context, individuals are bound to face the propaganda, designed by firms as a communication strategy. The study is exploratory is nature. The study is done using secondary data from published sources. In our study, we try and study a particular type of communication strategy, propaganda, which employs questionable techniques, through a comprehensive literature review. We try and understand the history and use of propaganda and how its research developed from its nascent stages and collaborated with various communications theories. We then take a look at the its contemporary usages and tools employed. It is pertinent to study the impact of propaganda on individual and the society. We explain that how individual/firms/society can use propaganda to build a communication strategy. Further, we theories and elaborate on the need for further research on this widely prevalent form of communication. Keywords: Propaganda, Internet, Communication, Persuasion, Politics, Social Network. INTRODUCTION Propaganda has been in operation in the world for a long time now.