Challenging the Convening Authority at Guantánamo Bay GTMO OBSERVER PROGRAM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Day Two of Military Judge Questioning 9/11 Accused About Self-Representation

Public amnesty international USA Guantánamo: Day two of military judge questioning 9/11 accused about self-representation 11 July 2008 AI Index: AMR 51/077/2008 On 10 July 2008, military commission judge US Marine Colonel Ralph Kohlmann held further proceedings to question the men accused of orchestrating the attacks of 11 September 2001 about their decision to represent themselves at their forthcoming death penalty trial in the US Naval Base in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. Amnesty International had an observer at the proceedings. The primary purpose of the hearings was to inquire of each of the accused individually about whether they had been intimidated before or during their arraignment on 5 June 2008 into making a choice to represent themselves, or whether this decision had been made knowingly and voluntarily. Judge Kohlmann had questioned two of the accused, ‘Ali ‘Abd al-‘Aziz ‘Ali (‘Ammar al Baluchi) and Mustafa al Hawsawi at individual sessions held on 9 July (see http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/info/AMR51/076/2008/en). He had scheduled sessions for the other three men, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, Walid bin Attash and Ramzi bin al-Shibh on 10 July. In the event, Ramzi bin al-Shibh refused to come to his session. It seems unlikely that the military judge will question him again on the matter of legal representation until the issue of Ramzi bin al-Shibh’s mental competency is addressed at a hearing scheduled to take place next month (see http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/info/AMR51/074/2008/en). Both Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and Walid bin Attash denied that they had been intimidated or that any intimidation had taken place. -

Observer Dispatch by Mary Ann Walker

Interrogating the Interrogator at Guantánamo Bay GTMO OBSERVER PROGRAM FEBRUARY 5, 2020 By: Mary Ann Walker As part of the Pacific Council’s Guantánamo Bay Observer Program, I traveled to Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, in January 2020 to attend the 9/11 military pre-trial hearing of alleged plotter and mastermind Khalid Sheik Mohammad and four others charged with assisting in the 9/11 attacks: Walid bin Attash, Ramzi bin al-Shibh, Ali Abdul Aziz Ali, and Mustafa al-Hawsawi. Pretrial hearings have been ongoing in Guantánamo Bay since 2008. The trial itself is scheduled to begin in January 2021, nearly 20 years after the 9/11 attacks. I was among 13 NGO observers from numerous organizations. Media outlets including Al Jazeera, The Guardian, the Los Angeles Times, and The New York Times were also present in order to cover this historic hearing along with many family members of the 9/11 victims. It was an eye-opening experience to be an observer. Defense attorney for Ali Abdul Aziz Ali, James Connell, met with the NGOs and media the evening we arrived on January 18. He explained the current status of pretrial hearings and what we could expect in the days to come. Chief Defense Counsel General John Baker met with the NGOs on Martin Luther King, Jr., Day to give background on the upcoming trial and military commissions. At the start of the meeting, Baker commended Pacific Council on International Policy for its excellent work on the three amendments to the FY2018 defense bill allowing for transparent and fair military commission trials in Guantánamo Bay, which includes the broadcast of the trials via the internet. -

The Oath a Film by Laura Poitras

The Oath A film by Laura Poitras POV www.pbs.org/pov DISCUSSION GUIDe The Oath POV Letter frOm the fiLmmakers New YorK , 2010 I was first interested in making a film about Guantanamo in 2003, when I was also beginning a film about the war in Iraq. I never imagined Guantanamo would still be open when I finished that film, but sadly it was — and still is today. originally, my idea for the Oath was to make a film about some - one released from Guantanamo and returning home. In May 2007, I traveled to Yemen looking to find that story and that’s when I met Abu Jandal, osama bin Laden’s former bodyguard, driving a taxicab in Sana’a, the capital of Yemen. I wasn’t look - ing to make a film about Al-Qaeda, but that changed when I met Abu Jandal. Themes of betrayal, guilt, loyalty, family and absence are not typically things that come to mind when we imagine a film about Al-Qaeda and Guantanamo. Despite the dangers of telling this story, it compelled me. Born in Saudi Arabia of Yemeni parents, Abu Jandal left home in 1993 to fight jihad in Bosnia. In 1996 he recruited Salim Ham - dan to join him for jihad in Tajikistan. while traveling through Laura Poitras, filmmaker of the Oath . Afghanistan, they were recruited by osama bin Laden. Abu Jan - Photo by Khalid Al Mahdi dal became bin Laden's personal bodyguard and “emir of Hos - pitality.” Salim Hamdan became bin Laden’s driver. Abu Jandal ends up driving a taxi and Hamdan ends up at Guantanamo. -

Print: Bush's Plan to Erode Our Liberties

Print: Bush's Plan to Erode Our Liberties http://www.thenation.com/doc/20070625/huq/print Bush's Plan to Erode Our Liberties by AZIZ HUQ June 8, 2007 Early this week, judge advocates halted two prosecutions in the Guantánamo military commissions established under the 2006 Military Commissions Act (MCA). This is not the first setback the Administration's second-tier court system has hit; the Supreme Court invalidated an earlier iteration of the commissions in 2006. And it won't be the last. But while this week's setback likely will be speedily surmounted, it casts an unexpected light on the MCA's real purposes, and what's at stake when the Bush Administration plays politics with national security. Understanding the significance of this week's ruling means delving into a bit of procedural arcana. The devil in the MCA is, almost literally, in the details--and unless we attend closely to the rococo details of the statute, we'll miss the ways in which the Administration intends to slowly erode our liberties. At the beginning of this week, the military commissions' two judges--Army Col. Peter Brownback and Navy Capt. Keith Allred--dismissed charges filed against Omar Khadr and Salim Hamdan. The rulings focused on a question of categorization--basically, the judges found that Khadr and Hamdan had been wrongly classified. But how did this happen? The MCA, which created the military commissions, states that only an alien who is an "unlawful enemy combatant" can be tried in a military commission. It also defines "unlawful enemy combatants" in tremendously sweeping terms to include anyone who has "materially supported hostilities." Many civil libertarians, including myself, expressed grave concerns about the scope of this provision. -

Forming and Maintaining Productive Client Relations with Al Qaeda Members and Their Supporters

FCDJ Volume V FORMING AND MAINTAINING PRODUCTIVE CLIENT RELATIONS WITH AL QAEDA MEMBERS AND THEIR SUPPORTERS 1 TRAVIS J. OWENS 1 This article is written in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the California Western School of Law L.L.M. in Trial Advocacy. My thanks to Professor Justin Brooks for his contributions to my writing process and to a host of attorneys and interpreters who provided their practical insights on the substance of this article. The author is a graduate of the University of Cincinnati College of Law (J.D.) and the Naval Postgraduate School (M.A. in Security Studies: Middle East, North Africa and South Asia.). He is a Lieutenant Commander in the United States Navy Judge Advocate General’s Corps. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the Department of Defense or the United States Navy. 50 FCDJ Volume V I. INTRODUCTION As a Federal Defender, you have just been assigned to the case of Ahmed Warsame, a Somalian general detained for two months on a ship by the United States, questioned by intelligence services, and now indicted in federal district court. The indictment alleges, among other things, that Mr. Warsame materially supported “Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.” As a defense attorney, you have represented a multitude of difficult clients - sexual predators, drug dealers with diagnosed mental disorders, and foreign nationals who speak no English and have never been in an American jail. You are respected for how you can win in court and for having brought clients to the table for deals that people thought could never be made. -

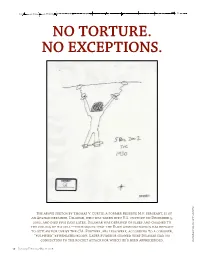

No Torture. No Exceptions

NO TORTURE. NO EXCEPTIONS. The above sketch by Thomas V. Curtis, a former Reserve M.P. sergeant, is of New York Times an Afghan detainee, Dilawar, who was taken into U.S. custody on December 5, 2002, and died five days later. Dilawar was deprived of sleep and chained to the ceiling of his cell—techniques that the Bush administration has refused to outlaw for use by the CIA. Further, his legs were, according to a coroner, “pulpified” by repeated blows. Later evidence showed that Dilawar had no connection to the rocket attack for which he’d been apprehended. A sketch by Thomas Curtis, V. a Reserve M.P./The 16 January/February/March 2008 Introduction n most issues of the Washington Monthly, we favor ar- long-term psychological effects also haunt patients—panic ticles that we hope will launch a debate. In this issue attacks, depression, and symptoms of post-traumatic-stress Iwe seek to end one. The unifying message of the ar- disorder. It has long been prosecuted as a crime of war. In our ticles that follow is, simply, Stop. In the wake of Septem- view, it still should be. ber 11, the United States became a nation that practiced Ideally, the election in November would put an end to torture. Astonishingly—despite the repudiation of tor- this debate, but we fear it won’t. John McCain, who for so ture by experts and the revelations of Guantanamo and long was one of the leading Republican opponents of the Abu Ghraib—we remain one. As we go to press, President White House’s policy on torture, voted in February against George W. -

Hearing for Majid Khan

C05403115 o (b)(1) (b)(3) Verbatim Transcript of Combatant Status Review Tribnnal Hearing for ISN 10020 OPENING PRESIDENT: This hearing shall come to order. RECORDER: This Tribunal is being conducted at 08:42 on 15 April 2007 on board U.S. Naval Base Guantanarno Bay, Cuba. The following personnel are present: Colonel United States Air Force, President, Commander United States Navy, Member, Lieutenant Colonel United States Air Force, Member, Major United States Air Force, Personal Representative, Sergeant First Class United States Army, Reporter, Major_United States Air Force, Recorder. Lieutenant Colonel_is the Judge Advocate member ofthe Tribunal. OATH SESSION 1 RECORDER: All rise. PRESIDENT: The Recorder will be sworn. Do you, Major-swear or affirm that you will faithfully perform the duties as ~signed in this Tribunal, so help you God? RECORDER: I do. PRESIDENT: The Reporter will now be sworn. The Recorder will administer the oath. RECORDER: Do you, Sergeant First Class swear that you will faithfully discharge your duties as Reporter assigned in this Tribunal, so help you God? REPORTER: [ do. PRESIDENT: We'll take a briefrecess while the Detainee is brought into the room. RECORDER: The time is 08:43 on IS Apri12007. This Tribunal is now in recess. All rise. [All personnel depart the room.] CONVENING AUTHORITY RECORDER: [All personnel return into the room at 08:48.] All rise. PRESIDENT: This hearing will come to order. You may be seated. Good morning. DETAINEE: Good morning. How are you guys doing? ISN # 10020 Enclosure (3) Page1 of50 C05403115 PRESIDENT: Very good, fine, thank you. This Tribunal is convened by order ofthe Director, Combatant Status Review Tribunals under the provisions ofhis Order of 12 February 2007. -

The Value of Claiming Torture: an Analysis of Al-Qaeda's Tactical Lawfare Strategy and Efforts to Fight Back, 43 Case W

Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law Volume 43 | Issue 1 2010 The alueV of Claiming Torture: An Analysis of Al- Qaeda's Tactical Lawfare Strategy and Efforts to Fight Back Michael J. Lebowitz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael J. Lebowitz, The Value of Claiming Torture: An Analysis of Al-Qaeda's Tactical Lawfare Strategy and Efforts to Fight Back, 43 Case W. Res. J. Int'l L. 357 (2010) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil/vol43/iss1/22 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. File: Lebowitz 2 Created on: 1/9/2011 9:48:00 PM Last Printed: 4/5/2011 8:09:00 PM THE VALUE OF CLAIMING TORTURE: AN ANALYSIS OF AL-QAEDA’S TACTICAL LAWFARE STRATEGY AND EFFORTS TO FIGHT BACK Michael J. Lebowitz* I. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................... 357 II. CLAIMING TORTURE TO SHAPE THE BATTLEFIELD .............................. 361 A. Tactical Lawfare ........................................................................... 362 B. Faux Torture ................................................................................. 364 C. The Torture Benchmark ............................................................... -

True and False Confessions: the Efficacy of Torture and Brutal

Chapter 7 True and False Confessions The Efficacy of Torture and Brutal Interrogations Central to the debate on the use of “enhanced” interrogation techniques is the question of whether those techniques are effective in gaining intelligence. If the techniques are the only way to get actionable intelligence that prevents terrorist attacks, their use presents a moral dilemma for some. On the other hand, if brutality does not produce useful intelligence — that is, it is not better at getting information than other methods — the debate is moot. This chapter focuses on the effectiveness of the CIA’s enhanced interrogation technique program. There are far fewer people who defend brutal interrogations by the military. Most of the military’s mistreatment of captives was not authorized in detail at high levels, and some was entirely unauthorized. Many military captives were either foot soldiers or were entirely innocent, and had no valuable intelligence to reveal. Many of the perpetrators of abuse in the military were young interrogators with limited training and experience, or were not interrogators at all. The officials who authorized the CIA’s interrogation program have consistently maintained that it produced useful intelligence, led to the capture of terrorist suspects, disrupted terrorist attacks, and saved American lives. Vice President Dick Cheney, in a 2009 speech, stated that the enhanced interrogation of captives “prevented the violent death of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of innocent people.” President George W. Bush similarly stated in his memoirs that “[t]he CIA interrogation program saved lives,” and “helped break up plots to attack military and diplomatic facilities abroad, Heathrow Airport and Canary Wharf in London, and multiple targets in the United States.” John Brennan, President Obama’s recent nominee for CIA director, said, of the CIA’s program in a televised interview in 2007, “[t]here [has] been a lot of information that has come out from these interrogation procedures. -

Waterboarding: Political and Sacred Torture Stephen F

chapter 9 Waterboarding: Political and Sacred Torture Stephen F. Eisenman The Scene of Politics After the release of photographs of tortured prisoners at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq in May 2003, a Gallup Poll indicated that 54 percent of Americans were “bothered a great deal” by the revelations. A year later the number had declined to 40 percent. In December 2005 an AP/IPSOS poll revealed that 61 percent of Americans agreed that torture was justifi ed, at least on some occasions.1 A May 2006 report by the UN High Commission for Human Rights about US torture at Guantánamo Bay was widely reported in newspapers, radio, and television, but produced no major outcries, public protests, or congressional investigations. Soon thereafter, President Bush— invoking the fi ctional “ticking bomb” scenario—successfully argued to Congress that the CIA should be allowed to use so-called “alternative interrogation procedures” and be given immunity from criminal prosecu- tion for prisoner abuse and war crimes. Despite the efforts of a few sena- tors, notably Patrick Leahy of Vermont, Sheldon Whitehouse of Rhode Island, and Joe Biden of Delaware, that immunity was granted. The US public and its representatives, it would seem, were not bothered by the fact 129 This content downloaded from 198.91.37.2 on Thu, 30 Jun 2016 01:27:50 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms CCarlson-Partarlson-Part IIII.inddII.indd 112929 77/2/2012/2/2012 44:54:33:54:33 PPMM 130 Stephen F. Eisenman that the US government permitted and even encouraged its agents to torture people held in their custody. -

Human Rights Watch All Rights Reserved

HUMAN RIGHTS Delivered Into Enemy Hands US-Led Abuse and Rendition of Opponents to Gaddafi’s Libya WATCH Delivered Into Enemy Hands US-Led Abuse and Rendition of Opponents to Gaddafi’s Libya Copyright © 2012 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-940-2 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org SEPTEMBER 2012 ISBN: 1-56432-940-2 Delivered Into Enemy Hands US-Led Abuse and Rendition of Opponents to Gaddafi’s Libya Summary ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Key Recommendations.................................................................................................................... -

Closing the Guantanamo Detention Center: Legal Issues

Closing the Guantanamo Detention Center: Legal Issues Michael John Garcia Legislative Attorney Jennifer K. Elsea Legislative Attorney R. Chuck Mason Legislative Attorney Edward C. Liu Legislative Attorney May 30, 2013 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R40139 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Closing the Guantanamo Detention Center: Legal Issues Summary Following the terrorist attacks of 9/11, Congress passed the Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF), which granted the President the authority “to use all necessary and appropriate force against those ... [who] planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks” against the United States. Many persons subsequently captured during military operations in Afghanistan and elsewhere were transferred to the U.S. Naval Station at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, for detention and possible prosecution. Although nearly 800 persons have been held at Guantanamo since early 2002, the substantial majority of Guantanamo detainees have been transferred to another country for continued detention or release. Those detainees who remain fall into three categories: (1) persons placed in non-penal, preventive detention to stop them from rejoining hostilities; (2) persons who face or are expected to face criminal charges; and (3) persons who have been cleared for transfer or release, whom the United States continues to detain pending transfer. Although the Supreme Court ruled in Boumediene v. Bush that Guantanamo detainees may seek habeas corpus review of the legality of their detention, several legal issues remain unsettled. In January 2009, President Obama issued an Executive Order to facilitate the closure of the Guantanamo detention facility within a year.