Forming and Maintaining Productive Client Relations with Al Qaeda Members and Their Supporters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Supreme Court of the United States

No. ________ In the Supreme Court of the United States KHALED A. F. AL ODAH, ET AL., PETITIONERS, v. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ET AL., RESPONDENTS. ON PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI DAVID J. CYNAMON THOMAS B. WILNER MATTHEW J. MACLEAN COUNSEL OF RECORD OSMAN HANDOO NEIL H. KOSLOWE PILLSBURY WINTHROP AMANDA E. SHAFER SHAW PITTMAN LLP SHERI L. SHEPHERD 2300 N Street, N.W. SHEARMAN & STERLING LLP Washington, DC 20037 801 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W. 202-663-8000 Washington, DC 20004 202-508-8000 GITANJALI GUTIERREZ J. WELLS DIXON GEORGE BRENT MICKUM IV SHAYANA KADIDAL SPRIGGS & HOLLINGSWORTH CENTER FOR 1350 “I” Street N.W. CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS Washington, DC 20005 666 Broadway, 7th Floor 202-898-5800 New York, NY 10012 212-614-6438 Counsel for Petitioners Additional Counsel Listed on Inside Cover JOSEPH MARGULIES JOHN J. GIBBONS MACARTHUR JUSTICE CENTER LAWRENCE S. LUSTBERG NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY GIBBONS P.C. LAW SCHOOL One Gateway Center 357 East Chicago Avenue Newark, NJ 07102 Chicago, IL 60611 973-596-4500 312-503-0890 MARK S. SULLIVAN BAHER AZMY CHRISTOPHER G. KARAGHEUZOFF SETON HALL LAW SCHOOL JOSHUA COLANGELO-BRYAN CENTER FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE DORSEY & WHITNEY LLP 833 McCarter Highway 250 Park Avenue Newark, NJ 07102 New York, NY 10177 973-642-8700 212-415-9200 DAVID H. REMES MARC D. FALKOFF COVINGTON & BURLING COLLEGE OF LAW 1201 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W. NORTHERN ILLINOIS Washington, DC 20004 UNIVERSITY 202-662-5212 DeKalb, IL 60115 815-753-0660 PAMELA CHEPIGA SCOTT SULLIVAN ANDREW MATHESON DEREK JINKS KAREN LEE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS SARAH HAVENS SCHOOL OF LAW ALLEN & OVERY LLP RULE OF LAW IN WARTIME 1221 Avenue of the Americas PROGRAM New York, NY 10020 727 E. -

Day Two of Military Judge Questioning 9/11 Accused About Self-Representation

Public amnesty international USA Guantánamo: Day two of military judge questioning 9/11 accused about self-representation 11 July 2008 AI Index: AMR 51/077/2008 On 10 July 2008, military commission judge US Marine Colonel Ralph Kohlmann held further proceedings to question the men accused of orchestrating the attacks of 11 September 2001 about their decision to represent themselves at their forthcoming death penalty trial in the US Naval Base in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. Amnesty International had an observer at the proceedings. The primary purpose of the hearings was to inquire of each of the accused individually about whether they had been intimidated before or during their arraignment on 5 June 2008 into making a choice to represent themselves, or whether this decision had been made knowingly and voluntarily. Judge Kohlmann had questioned two of the accused, ‘Ali ‘Abd al-‘Aziz ‘Ali (‘Ammar al Baluchi) and Mustafa al Hawsawi at individual sessions held on 9 July (see http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/info/AMR51/076/2008/en). He had scheduled sessions for the other three men, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, Walid bin Attash and Ramzi bin al-Shibh on 10 July. In the event, Ramzi bin al-Shibh refused to come to his session. It seems unlikely that the military judge will question him again on the matter of legal representation until the issue of Ramzi bin al-Shibh’s mental competency is addressed at a hearing scheduled to take place next month (see http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/info/AMR51/074/2008/en). Both Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and Walid bin Attash denied that they had been intimidated or that any intimidation had taken place. -

BA Oppgave.Pages

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! «…It’s nothing but torture» It’s time for a serious reaction to music torture ! Inger-Maren Helliksen Fjeldheim May 18th! 2018 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! "1 av "17 !Abstract For years music has been used as a method of torture in American run prisons such as Bagram and Guantanamo. The American government calls it harsh interrogation and claim the music torture is kinder and less severe as it does not inflict physical damage on the prisoner. ! It is not within our power to know whether death is worse a fate for humans than a life of trauma. !Before we know this for certain, we cannot to claim that one fate is better or worse than the other. Musicians have known for a long time that their music is used for torture, and yet there as been little to no reaction. As musicians and music lovers we cannot sit idly by while what is supposed to be a source of comfort and happiness, is used for such deplorable purpose. It is time for a serious reaction to music torture. ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! "2 av "17 Index ! Abstract 2 ! I Introduction 3 ! II Music and Torture- What it is and where it comes from 4 ! III The Use of a Song- Drowning Pool and their song Bodies 5 ! IV What happens in Guantanamo 8 ! V Discussion- Time to react 8 ! VII Bibliography 11 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! "3 av "17 Introduction Music as a phenomenon is universal to all humans and can be found in every human culture past and present.1 It has been used through history for pleasure, and for sorrow, in religion and everyday life alike. -

Observer Dispatch by Mary Ann Walker

Interrogating the Interrogator at Guantánamo Bay GTMO OBSERVER PROGRAM FEBRUARY 5, 2020 By: Mary Ann Walker As part of the Pacific Council’s Guantánamo Bay Observer Program, I traveled to Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, in January 2020 to attend the 9/11 military pre-trial hearing of alleged plotter and mastermind Khalid Sheik Mohammad and four others charged with assisting in the 9/11 attacks: Walid bin Attash, Ramzi bin al-Shibh, Ali Abdul Aziz Ali, and Mustafa al-Hawsawi. Pretrial hearings have been ongoing in Guantánamo Bay since 2008. The trial itself is scheduled to begin in January 2021, nearly 20 years after the 9/11 attacks. I was among 13 NGO observers from numerous organizations. Media outlets including Al Jazeera, The Guardian, the Los Angeles Times, and The New York Times were also present in order to cover this historic hearing along with many family members of the 9/11 victims. It was an eye-opening experience to be an observer. Defense attorney for Ali Abdul Aziz Ali, James Connell, met with the NGOs and media the evening we arrived on January 18. He explained the current status of pretrial hearings and what we could expect in the days to come. Chief Defense Counsel General John Baker met with the NGOs on Martin Luther King, Jr., Day to give background on the upcoming trial and military commissions. At the start of the meeting, Baker commended Pacific Council on International Policy for its excellent work on the three amendments to the FY2018 defense bill allowing for transparent and fair military commission trials in Guantánamo Bay, which includes the broadcast of the trials via the internet. -

A Review of the FBI's Involvement in and Observations of Detainee Interrogations in Guantanamo Bay, Mghanistan, and Iraq

Case 1:04-cv-04151-AKH Document 450-5 Filed 02/15/11 Page 1 of 21 EXHIBIT 4 Case 1:04-cv-04151-AKH Document 450-5 Filed 02/15/11 Page 2 of 21 U.S. Department ofJustice Office of the Inspector General A Review of the FBI's Involvement in and Observations of Detainee Interrogations in Guantanamo Bay, Mghanistan, and Iraq Oversight and Review Division Office of the Inspector General May 2008 UNCLASSIFIED Case 1:04-cv-04151-AKH Document 450-5 Filed 02/15/11 Page 3 of 21 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .i CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION 1 I. Introduction l II. The OIG Investigation 2 III. Prior Reports Regarding Detainee Mistreatment 3 IV. Methodology of OIG Review of Knowledge of FBI Agents Regarding Detainee Treatment · 5 A. The OIG June 2005 Survey 5 B. OIG Selection of FBI Personnel for.Interviews 7 C. OIG Treatment of Military Conduct 7 V. Organization of the OIG Report 8 CHAPTER TWO: FACTUAL BACKGROUND 11 I. The Changing Role of the FBI After September 11 11 II. FBI Headquarters Organizational Structure for Military Zones 12 A. Counterterrorism Division 13 1. International Terrorism Operations Sections 13 2. Counterterrorism Operations Response Section 14 B. Critical Incident Response Group 15 C. Office of General Counsel. 15 III. Other DOJ Entities Involved in Overseas Detainee Matters 16 IV. Inter-Agency Entities and Agreements Relating to Detainee Matters. 16 A. The Policy Coordinating Committee 16 B. Inter-Agency Memorandums of Understanding 18 V. Background Regarding the FBI's Role in the Military Zones 19 A. -

Who Is Shaker Aamer? Crt Briefing, 9 February 2015

BRITAIN’S LAST GUANTÁNAMO DETAINEE: WHO IS SHAKER AAMER? CRT BRIEFING, 9 FEBRUARY 2015 INTRODUCTION It is UK government policy that Shaker Aamer, the last remaining British resident detained at Guantánamo Bay, be returned. In December 2014, newspaper stories emerged suggesting that this could soon be the case.1 At a meeting in Washington, DC, a month later, President Obama told Prime Minister David Cameron that the US would “prioritise” the case.2 Aamer, who was born in Saudi Arabia, was captured in Afghanistan in November 2001; he was sent to Guantánamo Bay in February 2002. The US government believes him to be a weapons-trained al- Qaeda fighter; Aamer’s supporters claim that he was in Afghanistan to carry out voluntary work for an Islamic charity.3 Aamer is thought to have been cleared for transfer to Saudi Arabia in June 2007 (although, as late as November 2007, Department of Defense documentation recommended that he continue to be 1 ‘Guantanamo to free last UK inmate’, The Sunday Times, 28 December 2014, available at: http://www.thesundaytimes.co.uk/sto/news/uk_news/National/article1500831.ece?CMP=OTH-gnws-standard-2014_12_27, last visited: 29 January 2015; see also: ‘Last British inmate at Guantanamo set to be freed in the new year in fresh push by Obama to empty prison’, Daily Mail, 28 December 2014, available at: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2888964/Last-British- inmate-Guantanamo-set-freed-new-year-fresh-push-Obama-prison.html, last visited: 29 January 2015. 2 ‘Barack Obama to “prioritise” case of Guantánamo detainee Shaker Aamer’, The Guardian, 16 January 2015, available at: http://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2015/jan/16/shaker-aamer-guantanamo-bay-prioritise-obama-case, last visited: 29 January 2015. -

Pakistan. Conference on Disappearances in Pakistan (Web

WEB UPDATES – TACTICAL CAMPAIGN AGAINST TORTURE Name/Team Edurne Rubio/ TCT ext. 5515 Date 25/09/2006 Section Features AIDOC ASA 33/037/2006 Title Wanted: al-Qa’ida suspects. $5000 reward. Summary for torture homepage More than 85% of detainees at Guantánamo Bay were arrested by the Afghan Northern Alliance and in Pakistan at a time when rewards of up to $5,000 were paid for every “terrorist” handed over to the USA. Family members, lawyers and other activists are gathering in Islamabad, Pakistan (29 to 31 September) to inform and encourage action against Pakistan’s increasing use of arbitrary arrest, secret detention, torture and the failure of Pakistani courts to offer protection.. Feature The road to Guantánamo starts in Pakistan. More than 85 percent of detainees unlawfully held at the US detention centre in Cuba were arrested by the Afghan Northern Alliance and in Pakistan at a time when rewards of up to US$5,000 were paid for every unidentified terror suspect handed over to the USA. Bounty hunters – including police officers and local people – took advantage of this routine practice that facilitated illegal detention and enforced disappearance, almost unheard in Pakistan before the US-led “war on terror”. The Pakistani courts have failed to offer protection. Hundreds of Pakistani and foreign nationals have been picked up in mass arrests in Pakistan since 2001, many have been “sold” to the USA as ‘terrorists’ simply on the word of their captor, and hundreds have been transferred to Guantánamo Bay, Bagram Airbase or secret detention centres run by the USA. -

Download the PDF File

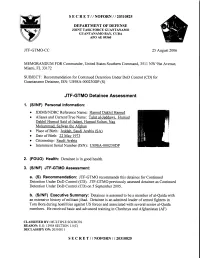

S E C RE T //NOFORN I I 20310825 DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE JOINT TASK FORCE GUANTANAMO GUANTANAMO BAY, CI,IBA APO AE 09360 JTF-GTMO-CC 25 August2006 MEMORANDUM FOR Commander,United StatesSouthern Command, 3511 NW 9lst Avenue. Miami. FL33172 SUBJECT: Recommendationfor Continued Detention Under DoD Control (CD) for GuantanamoDetainee, ISN: US9SA-000230DP(S) JTF-GTMODetainee Assessment 1. (S/NF) PersonalInformation: o JDIMSAIDRC ReferenceName: Hamud Dakhil Hamud o Aliases and Current/True Name: Talut al-Jeddawi. Humud Dakhil Humud Said al-Jadani.Hamud Sultan.Nag Mohammad. Safwan the Afghan o Placeof Birth: Jeddah.Saudi Arabia (SA) o Dateof Birth: 22May 1973 o Citizenship: SaudiArabia o InternmentSerial Number (ISN): US9SA-000230DP 2. (FOUO) Health: Detaineeis in goodhealth. 3. (S//NF) JTF-GTMOAssessment: a. (S) Recommendation: JTF-GTMOrecommends this detaineefor Continued DetentionUnder DoD Control(CD). JTF-GTMOpreviously assessed detainee as Continued DetentionUnder DoD Control(CD) on 5 September2005. b. (S/NF) Executive Summary: Detaineeis assessedto be a memberof al-Qaidawith an extensivehistory of militantjihad. Detaineeis an admittedleader of armedfighters in ToraBora duringhostilities against US forcesand associated with severalsenior al-Qaida members.He receivedbasic and advanced training in Chechnyaand Afghanistan (AF) CLASSIFIEDBY: MULTIPLESOURCES REASON:E.O. 12958 SECTION 1.5(C) DECLASSIFYON: 203108 1 I S E C RE T // NOFORNI I 20310825 S E C R E T // NOFORNI I 20310825 JTF-GTMO-CC SUBJECT:Recommendation for ContinuedDetention Under DoD Control(CD) for GuantanamoDetainee, ISN: US9SA-000230DP (S) includingtraining on smallarns, explosives,mortars, and anti-aircraft weaponry. JTF- GTMO determinedthis detaineeto be: o A HIGH risk, as he is likely to posea threatto the US, its interestsand allies. -

Katznelson.Pdf

THE RULE OF LAW ORAL HISTORY PROJECT The Reminiscences of Zachary P. Katznelson Columbia Center for Oral History Columbia University 2013 PREFACE The following oral history is the result of a recorded interview with Zachary P. Katznelson conducted by Ronald J. Grele on March 7 and March 13, 2013. This interview is part of the Rule of Law Oral History Project. The reader is asked to bear in mind that s/he is reading a verbatim transcript of the spoken word, rather than written prose. 3PM Session One Interviewee: Zachary P. Katznelson Location: New York, NY Interviewer: Ronald J. Grele Date: March 7, 2013 Q: I guess where I'd like to start is to talk about where you were born, and where you grew up, and where you went to school, and when you were a kid. Katznelson: When I was a kid? Q: Oh, could you hook that up to your sweater? That's why I wasn't getting the light. Okay. Katznelson: That better? Q: Yes. Katznelson: Okay. So I was born in New York City in 1973, and I grew up in Manhattan and in Chicago for a number of years. We moved to Chicago when I was just a baby and moved back to New York when I was nine. My father [Ira Katznelson] is a professor; he's now at Columbia [University]—was at Columbia when I was born, and was at the University of Chicago for a while. So I grew up in both places. I definitely consider myself a New Yorker. Most of my family's from New York—most of my family who is still alive is in New York, so this is really home. -

Moazzam Begg

REPORT ONE THOUSAND DAYS AND NIGHTS OF TORTURE The Systematic Torture and Abuse of Moazzam Begg a British Citizen by the United States of America November 24, 2004 (Sexual Abuse I Mental Health Redacted) 000268 - -- --- --- TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Death, Torture by threats of .............................................. -1- a. Threats of summaryjudicial execution -1- b. Witnessing the murder of other prisoners -2- 1. The First Murder: Two MP's beat aY oung Afghan to death -2- 11. The SecondMurder:Aparticularly SadisticMPbeats anotherAfghan to death. .. -3- 2. Physical Torture (Torture in the First Degree) . .. -4- a. BeatingsofMr.Begg. ... ... ... .. ... .. .. -4- 1. Beating the Prisoner with Truncheons . .. -4- 11. Stomping on the Prisoner's the Feet -4- lll. Beating Mr. Begg about the head. .. -4- iv. Beating Mr. Begg about the ears (Telefono) -5- b. Kicking Mr. Begg -5- c. Cold / Hypothermia used as Physical Torture -5- d. Guns used to Threaten Mr. Begg's life -5- 1. Direct threats with guns . .. -5- 11. Direct threats with tasers -6- e. Stress & Duress Physical Abuse -6- 1. Duress Positions . .. -6- 11. The "Marching Position" -6- lll. The "Torture Position" -7- -1- 000269 - -- - ---- -- - - -- - -- f. Physical abuse by Shackling -7- 1. Shackling Generally . .. -7- 11. Suspension by Shackling .............................. -7- (1) TheAmerianvariationonthe ReverseStrappado. .. -7- (2) The American version of Strappado -8- 3. Torture by Rape & Sexual Abuse -8- 4. Threats of Rendition (Outsourcing Torture) -8- 5. Threats of Torture and Abuse (Second Degree Torture) -10- a. Threats against Mr. Begg's wife and children. .. -10- 1. ThreatsagainstMr.Begg'swife Sally. .. -10- 11. Threats against Mr. Begg's children -11- b. -

The Virtues and Vices of Advocacy Strategies in the War on Terror

Roger Williams University DOCS@RWU Law Faculty Scholarship Law Faculty Scholarship 4-2009 The etD ainees' Dilemma: The irV tues and Vices of Advocacy Strategies in the War on Terror Peter Margulies Roger Williams University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://docs.rwu.edu/law_fac_fs Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, International Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation Peter Margulies, The eD tainees' Dilemma: The irV tues and Vices of Advocacy Strategies in the War on Terror, 57 Buff. L. Rev. 347, 432 (2009) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Faculty Scholarship at DOCS@RWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of DOCS@RWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. +(,121/,1( Citation: 57 Buff. L. Rev. 347 2009 Provided by: Roger Williams University School of Law Library Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline Thu Nov 17 10:09:44 2016 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: Copyright Information BUFFALO LAW REVIEW VOLUME 57 APRIL 2009 NUMBER 2 The Detainees' Dilemma: The Virtues and Vices of Advocacy Strategies in the War on Terror PETER MARGULIESt INTRODUCTION For detainees in the war on terror, advocacy outside of court is often the main event.' Analysis of advocacy through the prism of Supreme Court decisions 2 resembles surveying t Professor of Law, Roger Williams University School of Law; e-mail: [email protected]. -

Hearing for Majid Khan

C05403115 o (b)(1) (b)(3) Verbatim Transcript of Combatant Status Review Tribnnal Hearing for ISN 10020 OPENING PRESIDENT: This hearing shall come to order. RECORDER: This Tribunal is being conducted at 08:42 on 15 April 2007 on board U.S. Naval Base Guantanarno Bay, Cuba. The following personnel are present: Colonel United States Air Force, President, Commander United States Navy, Member, Lieutenant Colonel United States Air Force, Member, Major United States Air Force, Personal Representative, Sergeant First Class United States Army, Reporter, Major_United States Air Force, Recorder. Lieutenant Colonel_is the Judge Advocate member ofthe Tribunal. OATH SESSION 1 RECORDER: All rise. PRESIDENT: The Recorder will be sworn. Do you, Major-swear or affirm that you will faithfully perform the duties as ~signed in this Tribunal, so help you God? RECORDER: I do. PRESIDENT: The Reporter will now be sworn. The Recorder will administer the oath. RECORDER: Do you, Sergeant First Class swear that you will faithfully discharge your duties as Reporter assigned in this Tribunal, so help you God? REPORTER: [ do. PRESIDENT: We'll take a briefrecess while the Detainee is brought into the room. RECORDER: The time is 08:43 on IS Apri12007. This Tribunal is now in recess. All rise. [All personnel depart the room.] CONVENING AUTHORITY RECORDER: [All personnel return into the room at 08:48.] All rise. PRESIDENT: This hearing will come to order. You may be seated. Good morning. DETAINEE: Good morning. How are you guys doing? ISN # 10020 Enclosure (3) Page1 of50 C05403115 PRESIDENT: Very good, fine, thank you. This Tribunal is convened by order ofthe Director, Combatant Status Review Tribunals under the provisions ofhis Order of 12 February 2007.