Viewing Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comic Strips and the American Family, 1930-1960 Dahnya Nicole Hernandez Pitzer College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pitzer Senior Theses Pitzer Student Scholarship 2014 Funny Pages: Comic Strips and the American Family, 1930-1960 Dahnya Nicole Hernandez Pitzer College Recommended Citation Hernandez, Dahnya Nicole, "Funny Pages: Comic Strips and the American Family, 1930-1960" (2014). Pitzer Senior Theses. Paper 60. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/pitzer_theses/60 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pitzer Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pitzer Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FUNNY PAGES COMIC STRIPS AND THE AMERICAN FAMILY, 1930-1960 BY DAHNYA HERNANDEZ-ROACH SUBMITTED TO PITZER COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE BACHELOR OF ARTS DEGREE FIRST READER: PROFESSOR BILL ANTHES SECOND READER: PROFESSOR MATTHEW DELMONT APRIL 25, 2014 0 Table of Contents Acknowledgements...........................................................................................................................................2 Introduction.........................................................................................................................................................3 Chapter One: Blondie.....................................................................................................................................18 Chapter Two: Little Orphan Annie............................................................................................................35 -

Dick Tracy.” MAX ALLAN COLLINS —Scoop the DICK COMPLETE DICK ® TRACY TRACY

$39.99 “The period covered in this volume is arguably one of the strongest in the Gould/Tracy canon, (Different in Canada) and undeniably the cartoonist’s best work since 1952's Crewy Lou continuity. “One of the best things to happen to the Brutality by both the good and bad guys is as strong and disturbing as ever…” comic market in the last few years was IDW’s decision to publish The Complete from the Introduction by Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy.” MAX ALLAN COLLINS —Scoop THE DICK COMPLETE DICK ® TRACY TRACY NEARLY 550 SEQUENTIAL COMICS OCTOBER 1954 In Volume Sixteen—reprinting strips from October 25, 1954 THROUGH through May 13, 1956—Chester Gould presents an amazing MAY 1956 Chester Gould (1900–1985) was born in Pawnee, Oklahoma. number of memorable characters: grotesques such as the He attended Oklahoma A&M (now Oklahoma State murderous Rughead and a 467-lb. killer named Oodles, University) before transferring to Northwestern University in health faddist George Ozone and his wild boys named Neki Chicago, from which he was graduated in 1923. He produced and Hokey, the despicable "Nothing" Yonson, and the amoral the minor comic strips Fillum Fables and The Radio Catts teenager Joe Period. He then introduces nightclub photog- before striking it big with Dick Tracy in 1931. Originally titled Plainclothes Tracy, the rechristened strip became one of turned policewoman Lizz, at a time when women on the the most successful and lauded comic strips of all time, as well force were still a rarity. Plus for the first time Gould brings as a media and merchandising sensation. -

AIR FORCE Magazine / July 2007 42

A Brush With the Air Force 42 AIR FORCE Magazine / July 2007 prototype for Corkin was Air Force Col. Milton Caniff was out front with “Terry and Philip Cochran, a noted World War II pilot and leader of air commandos in the Pirates,” but other cartoonists also found Burma. (See “The All-American Air- their calling in the wild blue yonder. man,” March 2000, p. 52.) He became a continuing character in “Terry.” In a famous “Terry and the Pirates” Sunday page from 1943, Corkin opened with, “Let’s take a walk, Terry,” and then delivered an inspirational talk about A Brush With the war and the Air Force as he and the newly fledged pilot Terry strolled around the flight line. The page was “read” into the Congressional Record and reported in the newspapers. Terry, Flip, and their colleagues had a great following among airmen, and the Air Force By John T. Correll the strip had considerable morale and public relations value. Gen. Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, Chief of the Army Air Forces, assigned an officer to as- sist Caniff with any technical details he needed. Caniff produced another strip, “Male Call,” without charge for camp and base newspapers. It featured Miss Lace, who was reminiscent of the Dragon Lady but less standoffish. It is difficult today to comprehend what a big deal the funnies used to be. Everybody read the comic strips. Characters were as well known as movie stars. The strips were printed much larger than present comic strips are. On Sunday, a popular strip might get a whole color page to itself. -

Leila Leiz • Stan Goldberg • the Gods of Mount Olympus

$8.95 in the USA ™ A TwoMorrows Publication No. 9, Summer 2015 Madman TM & © 2015 Michael Allred. Flaming Carrot Bob Burden. E-Man & Nova TM & © 2015 Joe T. Staton. Femme Noir TM & © 2015 Christopher Mills & Joe Staton. Staton. Femme Noir TM & © 2015 Christopher Mills Joe E-Man & Nova TM © 2015 Joe T. 0 3 1 82658 97073 4 also: LEILA LEIZ • STAN GOLDBERG • THE GODS OF MOUNT OLYMPUS • KATIE GREEN Summer 2015 • Voice of the Comics Medium • Number 9 TABLE OF CONTENTS Ye Ed’s Rant: The Tyranny of Time ................................................................................... 2 E-WOODY COMICS CHATTER CBC mascot by J.D. KING Remembering Seth Kushner: The late photographer/writer’s good friend and ©2015 J.D. King. collaborator Christopher Irving recalls the recently departed CBC contributor ................ 3 About Our Cover Katie Green: An interview with the Lighter Than My Shadow graphic novelist ............ 4 Aushenkerology: A personal ode to Cowboy Henk and the great European comics .... 6 Art by JOE STATON Color by MATT WEBB Incoming: The Therapeutic Value of “It” and Roy Thomas on Kull the Conqueror ....... 10 The Good Stuff: George Khoury talks with artist Leila Leiz about living the dream ..... 14 Hembeck’s Dateline: Our Man Fred chats up longtime pal Joe Staton ...................... 17 Stan Goldberg: Part one of Richard J. Arndt’s interview with the late cartoonist and Marvel colorist, a man remarkably appreciative for his long career in comics ....... 18 GODS OF MOUNT OLYMPUS SPECIAL SECTION Johnny Lee Achziger’s Olympian Achievement: CBC’s three-part examination of a little-known but breathtaking 1970s comics project starts with recollections of the guy who authored and helmed the tabloid-size (and ill-fated) series .......... -

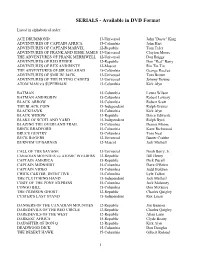

SERIALS - Available in DVD Format

SERIALS - Available in DVD Format Listed in alphabetical order: ACE DRUMMOND 13-Universal John "Dusty" King ADVENTURES OF CAPTAIN AFRICA 15-Columbia John Hart ADVENTURES OF CAPTAIN MARVEL 12-Republic Tom Tyler ADVENTURES OF FRANK AND JESSE JAMES 13-Universal Clayton Moore THE ADVENTURES OF FRANK MERRIWELL 12-Universal Don Briggs ADVENTURES OF RED RYDER 12-Republic Don "Red" Barry ADVENTURES OF REX AND RINTY 12-Mascot Rin Tin Tin THE ADVENTURES OF SIR GALAHAD 15-Columbia George Reeves ADVENTURES OF SMILIN' JACK 13-Universal Tom Brown ADVENTURES OF THE FLYING CADETS 13-Universal Johnny Downs ATOM MAN v/s SUPERMAN 15-Columbia Kirk Alyn BATMAN 15-Columbia Lewis Wilson BATMAN AND ROBIN 15-Columbia Robert Lowery BLACK ARROW 15-Columbia Robert Scott THE BLACK COIN 15-Independent Ralph Graves BLACKHAWK 15-Columbia Kirk Alyn BLACK WIDOW 13-Republic Bruce Edwards BLAKE OF SCOTLAND YARD 15-Independent Ralph Byrd BLAZING THE OVERLAND TRAIL 15-Columbia Dennis Moore BRICK BRADFORD 15-Columbia Kane Richmond BRUCE GENTRY 15-Columbia Tom Neal BUCK ROGERS 12-Universal Buster Crabbe BURN'EM UP BARNES 12-Mascot Jack Mulhall CALL OF THE SAVAGE 13-Universal Noah Berry, Jr. CANADIAN MOUNTIES v/s ATOMIC INVADERS 12-Republic Bill Henry CAPTAIN AMERICA 15-Republic Dick Pucell CAPTAIN MIDNIGHT 15-Columbia Dave O'Brien CAPTAIN VIDEO 15-Columbia Judd Holdren CHICK CARTER, DETECTIVE 15-Columbia Lyle Talbot THE CLUTCHING HAND 15-Independent Jack Mulhall CODY OF THE PONY EXPRESS 15-Columbia Jock Mahoney CONGO BILL 15-Columbia Don McGuire THE CRIMSON GHOST 12-Republic -

List of Shows Master Collection

Classic TV Shows 1950sTvShowOpenings\ AdventureStory\ AllInTheFamily\ AManCalledShenandoah\ AManCalledSloane\ Andromeda\ ATouchOfFrost\ BenCasey\ BeverlyHillbillies\ Bewitched\ Bickersons\ BigTown\ BigValley\ BingCrosbyShow\ BlackSaddle\ Blade\ Bonanza\ BorisKarloffsThriller\ BostonBlackie\ Branded\ BrideAndGroom\ BritishDetectiveMiniSeries\ BritishShows\ BroadcastHouse\ BroadwayOpenHouse\ BrokenArrow\ BuffaloBillJr\ BulldogDrummond\ BurkesLaw\ BurnsAndAllenShow\ ByPopularDemand\ CamelNewsCaravan\ CanadianTV\ CandidCamera\ Cannonball\ CaptainGallantOfTheForeignLegion\ CaptainMidnight\ captainVideo\ CaptainZ-Ro\ Car54WhereAreYou\ Cartoons\ Casablanca\ CaseyJones\ CavalcadeOfAmerica\ CavalcadeOfStars\ ChanceOfALifetime\ CheckMate\ ChesterfieldSoundOff\ ChesterfieldSupperClub\ Chopsticks\ ChroniclesOfNarnia\ CimmarronStrip\ CircusMixedNuts\ CiscoKid\ CityBeneathTheSea\ Climax\ Code3\ CokeTime\ ColgateSummerComedyHour\ ColonelMarchOfScotlandYard-British\ Combat\ Commercials50sAnd60s\ CoronationStreet\ Counterpoint\ Counterspy\ CourtOfLastResort\ CowboyG-Men\ CowboyInAfrica\ Crossroads\ DaddyO\ DadsArmy\ DangerMan-S1\ DangerManSeason2-3\ DangerousAssignment\ DanielBoone\ DarkShadows\ DateWithTheAngles\ DavyCrockett\ DeathValleyDays\ Decoy\ DemonWithAGlassHand\ DennisOKeefeShow\ DennisTheMenace\ DiagnosisUnknown\ DickTracy\ DickVanDykeShow\ DingDongSchool\ DobieGillis\ DorothyCollins\ DoYouTrustYourWife\ Dragnet\ DrHudsonsSecretJournal\ DrIQ\ DrSyn\ DuffysTavern\ DuPontCavalcadeTheater\ DupontTheater\ DustysTrail\ EdgarWallaceMysteries\ ElfegoBaca\ -

![1939-03-22 [P A-13]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9546/1939-03-22-p-a-13-2339546.webp)

1939-03-22 [P A-13]

Capitals Radio Program TODAY'S PROGRAM. MARCH 22, 1939. P.M. i . WMAL, 630k. , WRC, 950k. WOL, 1,230k. i WJSV, 1,460k. 3:66 Blinci Renard (Mary Marlin, serial (News—Sports Aladdin's Kitchen 3:15 Variety Program !Ma Perkins, serial Wakeman'j " " " " Sports 3:30 Pepper Young, serial i The Grab Bag " " _3:45_Between Book Ends Guiding Light, serial 4:00 Club Matinee : Backstage Wife Wakeman'j Sports IThe Grab Bag 4:15 Tune Types Stella Dallas, serial 4:30 Evening Star Flashes Vic and Sade, serial ** " 4:45 President Lebrun _J Girl Alone, serial_** _Local Jtews_ 5:00 (Jimmy Allen, serial (Dick Tracy, serial Mark Love, basso (The Grab Bag 5:15 !Terry and Pirates (Your Family, serial -Jimmy Scribner 5:30 ,0on Winslow, serial (Jack Armstrong ;Cocktail Capers (Melody Madcaps _5:4SjTom_Mix _Orphan Annie, serial (Musical Mystery 'Mighty Show, serial 6:00 Our Schools j News—Paradise (Sports Resume (News—Music 6:t5 News—Music Buccaneers (Sucker School iHowia Wing 6:30 Intermezzo Rhythm Makers i Walter Compton, news Le Brun in London 6:45 Lowell Thomas, news _"_Variety Program_:Sophie Tucker 7:00 (Easy Aces, serial Amos and Andy Fulton Lewis, jr. (Music-Without~End 7:15 (Mr. Keen, drama (Edwin C. Hill, news Rose d'Amore, piano Lum and Abner 7.30 Revelers, songs iTropical Moods Lone serial (Ask-lt-Besket " Ranger, 7:45 Serenade _Sir Willmott_ Lewis_| _| " 8:00 House One Man's Family Orch. Busters, drama (Open" " " iHeidelberg Gang 0:13 Orrin Tucker's Orch. 8:30 Hobby Orch. Hew York Fair Whiteman's " Lobby Tommy Dorsey's Pgm. -

Hollywood Extravaganza Auction VI

Welcome to Hollywood Live Auction’s Holiday Extravaganza Live Auction event weekend. We have assembled an incredible collection of rare iconic movie props and costumes featuring items from fi lm, television and music icons including John Wayne, Marilyn Monroe, Christopher Reeve, Michael Jackson, Don HollywoodJohnson and Kirk Douglas. Extravaganza Auction VI From John Wayne’s Pittsburgh costume, Michael Jackson’s deed and signed check to Th e Neverland Ranch, signed Billie Jean lyrics and signed, stage worn Fedora from the HIStory Tour, James Brown’s stage worn jumpsuit, Marilyn Monroe’sDay 2 gold high heels, Christopher Reeve’s Superman costume, Steve McQueen’s Enemy of the People costume, Robert Redford’s Th e Natural costume, Kirk Douglas’ Top Secret Aff air costume, Johnny Depp’s Blow costume, Don Johnson and Philip Michael Th omas’ Miami Vice costumes, and many more! Also from the new Immortals starring Mickey Rourke, bring home some of the most detailed costumes and props from the fi lm! If you are new to our live auction events and would like to participate, please register online at HollywoodLiveAuctions.com to watch and bid live. If you would prefer to be a phone bidder and be assisted by one of staff members, please call us to register at (866) 761-7767. We hope you enjoy Hollywood Live Auctions’ Holiday Extravaganza event and we look forward to seeing you on March 24th – 25th for Hollywood Live Auctions’ Auction Extravaganza V. Special thanks to everyone at Premiere Props for their continued dedication in producing these great events. Have fun and enjoy the weekend! Sincerely, Dan Levin Executive VP Marketing CALL TO BID @ 1-888-761-PROP (7767) 109 Lot 502. -

Calling Dick Tracy! Or, Cellphone Use, Progress, and a Racial Paradigm Judith A

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Communication Studies Faculty Publications Communication Studies 2008 Calling Dick Tracy! Or, Cellphone Use, Progress, and a Racial Paradigm Judith A. Nicholson Wilfrid Laurier University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholars.wlu.ca/coms_faculty Recommended Citation Nicholson, Judith A., "Calling Dick Tracy! Or, Cellphone Use, Progress, and a Racial Paradigm" (2008). Communication Studies Faculty Publications. 17. http://scholars.wlu.ca/coms_faculty/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication Studies at Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Studies Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Calling Dick Tracy! or, Cellphone Use, Progress, and a Racial Paradigm1 Judith A. Nicholson Wilfrid Laurier University Abstract: The hero and phone-watch from Dick Tracy are evoked regularly in news and studies of cellphone use. This paper argues that the racial paradigm of White law enforcer and Dark law-breaker in the comic strip resonates in con- temporary evocations and in discussions of cellphone use and crime. Representations of mobile communication and racialized criminality in Dick Tracy were inspired by the 1930s “war on crime” that intersected with wireless innovations and with lynching. This paper interprets that repeated evocation of the comic strip is a “perverse nostalgia” for an old-fashioned form of law and order premised on racialized violence and viewing. Keywords: Cultural analysis Résumé : Les études et nouvelles sur l’utilisation du téléphone cellulaire font souvent référence au détective de bande dessinée Dick Tracy et à sa montre téléphonique. -

Teatro REXI Cuenta Y Cuatro Años, Y Que Último Estilo Y Ma- Juntamente Con El Finado Dr

Viernes 13 de Octubre de 1939 “EL MENSAJERO” Pagina Tres JOVEN MUERTA DOS CARTAS ABIERTAS AL VOLCARSE EL PLEGARIA Por Antonio R. Redondo voto de gracias, me suscri- Yo conocí a una niña que ( Lo primero que encuentro bo todo el santo día de Dios lo AUTOMOVIL A Mis Hijos) al abrir mi correspondencia Su atenta servidora pasaba con hojas de higuera Mildred Hellen Robinson, Yo, le pido reverente, al Ser Omnipotente, de hoy es la siguiente carta, MANUELA BRINGAS. pegadas a la cara, para pro- joven de 22 años, murió en con toda el alma, con todo el corazón, copia que . textual: vocar la irritación del cutis, ¡ Sacatón a consecuencia de sea con mis hijos, por piedad: Clemente , y aparecer como una amapo- 1 lesiones recibidas al volcarse y que derrame sobre éllos, su Santa Bendición. Pues, verá usted mi seño- la al sentarse a la ventana. 1 Phoenix, Sept. 7, 1939 el automóvil que arreaba en rita Manuela—porque supon- Por supuesto que luego que el camino de Chandler-Cool- Que ilumine la senda que caminan Sr. A. R. Redondo, go será usted una señorita — llegaba la noche todo se le idge y Casa Grande. por el mundo, y que siempre hagan el bien, Los Angeles. ponerse que desprecien me ha puesto usted en un a- ¦ iba en fieltros de a- Según investigaciones he- las que fulminan prieto; porque descolgárseme gua helada. y al fin de la jornada, perdónalos también. Muy señor mío: chas por Charles H. Muders- ¦ r " con esa carlita, a mí que no pasado escribí De otra muchacha sé que bach, policía de caminos, el : ¿£i En Febrero soy doctor ni cosa que se le ¡ A todos les consagro, mimos y caricias, a Ud. -

The Drink Tank

There seems to be a universal rule araound these parts; when things seem to be going well, a computer crashes. CorFlu ended, everything went pretty well, then my computer crashed. All the art I gathered. All the issues I’d been working on. Every back issue of my zines, including the dining guides for various cons. Gone. All gone. Everything, gone. Not even recoverable on the drive for some reason. Something truly terrible hap- pened that must have blanked everything off the drive. I mean NOTHING is left. When I had it read, it was blank. Not there were sig- nificant sectors gone or corrupted, but there was nothin’ there! I mean nothin’. It sucks. So, this one has been delayed twice, first by prep for CorFlu, which went really well and I had such a blast that you can read about in the up-coming issue of Claims Department, and then by the crash. Is sorrow. OK, this issue is the Flash Gordon issue. I just got another article from Taral that I’ll run next week, after I’ve hopefully put together some more art and the like, and that’ll be an- other article in the 52 Weeks project. Which one? Well, you’ll figure it out shortly. That’s a cover by Mo Starkey, by the way. She did most of the Art gathering for this one! I love it when Mo does the covers. She’s a great one, she is. And I’ll probably be over CorFlu in the next month. I’m still pooped. -

A Holmes and Doyle Bibliography

A Holmes and Doyle Bibliography Volume 7 Audio/Visual Materials Alphabetical Listing Compiled by Timothy J. Johnson Minneapolis High Coffee Press 2018 A Holmes & Doyle Bibliography Vol. 7, Audio/Visual Materials, Alphabetical Listing INTRODUCTION This bibliography is a work in progress. It attempts to update Ronald B. De Waal’s comprehensive bibliography, The Universal Sherlock Holmes, but does not claim to be exhaustive in content. New works are continually discovered and added to this bibliography. Readers and researchers are invited to suggest additional content. This volume contains an alphabetical listing of audio-visual materials. Coverage of this material begins around 1994, the final year covered by De Waal's bibliography, but may not yet be totally up-to-date (given the ongoing nature of this bibliography). It is hoped that other titles will be added at a later date. The first volume in this supplement focuses on monographic and serial titles, arranged alphabetically by author or main entry. The second volume presents the exact same information arranged by subject. The third volume focuses on the periodical literature of Doyle and Holmes, listing individual articles alphabetically. The fourth volume includes "core" or "primary" citations from the periodical literature. The fifth volume includes "passing" or "secondary" references to Doyle or Holmes in the periodical literature. The sixth volume organizes the periodical literature according to De Waal's original categories. As the bibliography expands, additional annotations will be provided in order to give the researcher a better idea on the exact Holmesian or Doylean reference contained in each article. The compiler wishes to thank Peter E.