Equality (Samya)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Imperial and the Colonized Women's Viewing of the 'Other'

Gazing across the Divide in the Days of the Raj: The Imperial and the Colonized Women’s Viewing of the ‘Other’ Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Vorgelegt von Sukla Chatterjee Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Hans Harder Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Benjamin Zachariah Heidelberg, 01.04.2016 Abstract This project investigates the crucial moment of social transformation of the colonized Bengali society in the nineteenth century, when Bengali women and their bodies were being used as the site of interaction for colonial, social, political, and cultural forces, subsequently giving birth to the ‘new woman.’ What did the ‘new woman’ think about themselves, their colonial counterparts, and where did they see themselves in the newly reordered Bengali society, are some of the crucial questions this thesis answers. Both colonial and colonized women have been secondary stakeholders of colonialism and due to the power asymmetry, colonial woman have found themselves in a relatively advantageous position to form perspectives and generate voluminous discourse on the colonized women. The research uses that as the point of departure and tries to shed light on the other side of the divide, where Bengali women use the residual freedom and colonial reforms to hone their gaze and form their perspectives on their western counterparts. Each chapter of the thesis deals with a particular aspect of the colonized women’s literary representation of the ‘other’. The first chapter on Krishnabhabini Das’ travelogue, A Bengali Woman in England (1885), makes a comparative ethnographic analysis of Bengal and England, to provide the recipe for a utopian society, which Bengal should strive to become. -

2021 Banerjee Ankita 145189

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ The Santiniketan ashram as Rabindranath Tagore’s politics Banerjee, Ankita Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 24. Sep. 2021 THE SANTINIKETAN ashram As Rabindranath Tagore’s PoliTics Ankita Banerjee King’s College London 2020 This thesis is submitted to King’s College London for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy List of Illustrations Table 1: No of Essays written per year between 1892 and 1936. -

Nandan Gupta. `Prak-Bibar` Parbe Samaresh Basu. Nimai Bandyopadhyay

BOOK DESCRIPTION AUTHOR " Contemporary India ". Nandan Gupta. `Prak-Bibar` Parbe Samaresh Basu. Nimai Bandyopadhyay. 100 Great Lives. John Cannong. 100 Most important Indians Today. Sterling Special. 100 Most Important Indians Today. Sterling Special. 1787 The Grand Convention. Clinton Rossiter. 1952 Act of Provident Fund as Amended on 16th November 1995. Government of India. 1993 Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action. Indian Institute of Human Rights. 19e May ebong Assame Bangaliar Ostiter Sonkot. Bijit kumar Bhattacharjee. 19-er Basha Sohidera. Dilip kanti Laskar. 20 Tales From Shakespeare. Charles & Mary Lamb. 25 ways to Motivate People. Steve Chandler and Scott Richardson. 42-er Bharat Chara Andolane Srihatta-Cacharer abodan. Debashish Roy. 71 Judhe Pakisthan, Bharat O Bangaladesh. Deb Dullal Bangopadhyay. A Book of Education for Beginners. Bhatia and Bhatia. A River Sutra. Gita Mehta. A study of the philosophy of vivekananda. Tapash Shankar Dutta. A advaita concept of falsity-a critical study. Nirod Baron Chakravarty. A B C of Human Rights. Indian Institute of Human Rights. A Basic Grammar Of Moden Hindi. ----- A Book of English Essays. W E Williams. A Book of English Prose and Poetry. Macmillan India Ltd.. A book of English prose and poetry. Dutta & Bhattacharjee. A brief introduction to psychology. Clifford T Morgan. A bureaucrat`s diary. Prakash Krishen. A century of government and politics in North East India. V V Rao and Niru Hazarika. A Companion To Ethics. Peter Singer. A Companion to Indian Fiction in E nglish. Pier Paolo Piciucco. A Comparative Approach to American History. C Vann Woodward. A comparative study of Religion : A sufi and a Sanatani ( Ramakrishana). -

Spring 2014 Issn 1476-6760

Issue 74 Spring 2014 Issn 1476-6760 Sutapa Dutta on Identifying Mother India in Bankimchandra Chatterjee’s Novels Rene Kollar on Convents, the Bible, and English Anti- Catholicism in the Nineteenth Century Alyssa Velazquez on Tupperware: An Open Container During a Decade of Containment Plus Twenty-one book reviews Getting to know each other Committee News www.womenshistorynetwork.org First Call for Papers HOME FRONTS: GENDER, WAR AND CONFLICT Women’s History Network Annual Conference 5-7 September 2014 at the University of Worcester Offers of papers are invited which draw upon the perspectives of women’s and gender history to discuss practical and emotional survival on the Home Front during war and conflict. Contributions of papers on a range of topics are welcome and may, for example, explore one of the following areas: • Food, domesticity, marriage and the ordinariness of everyday life on the Home Front • The arts, leisure and entertainment during military conflict • Women’s working lives on the Home Front • Shifting relations of power around gender, class, ethnicity, religion or politics • Women’s individual or collective strategies and tactics for survival in wartime • Case studies illuminating the particularity of the Home Front in cities, small towns or rural areas • Outsiders on the Home Front including Image provided by - The Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology Service attitudes to prisoners of war, refugees, immigrants and travellers • Comparative Studies of the Home Front across time and geographical location • Representation, writing and remembering the Home Front Although the term Home Front was initially used during the First World War, and the conference coincides with the commemorations marking the centenary of the beginning of this conflict, we welcome papers which explore a range of Home Fronts and conflicts, across diverse historical periods and geographical areas. -

Actresses on Bengali Stage—Nati Binodini and Moyna: the Present Re-Imagines the Past

Actresses on Bengali Stage—Nati Binodini and Moyna: the Present Re-imagines the Past Madhumita Roy and Debmalya Das. Visva Bharati, Santiniketan. India. Abstract The Bengal Renaissance ushered in the process of multifaceted modernization resulting in the major reshaping of the theatrical space both in terms of convention and praxis. Abandoning the convention of cross–dressing (where the earlier male actors were dressed as women to represent female characters), this new theatrical space began to accommodate the women actors for the representation of female characters. Parallel with the emergence of the “New Woman” in the upper middle class society of the nineteenth century, the women actors also constituted a segregated sphere of the emancipated women. Although “free” to encounter the public sphere, they were denied the degree of social acceptability/status that was otherwise available to the then upper middle class “New Women.” This paper tries to locate the experience of a female actor of nineteenth century: Binodini Dasi: as is rendered in her two short autobiographical writings and the re-imagination of that experience in the twentieth century play Tiner Taloar by Utpal Dutt. Dutt uses the historical material to explore the consolidation and redefinition of the feminine space in his contemporary theatre. [Keywords: theatre, actress, performance, prostitution, protest, commodification, liberty.] The Bengal Renaissance ushered in the process of multifaceted modernization resulting in the major reshaping of the theatrical space both in terms of convention and praxis. Abandoning the convention of cross–dressing (whereas the earlier male actors were dressed as women to represent female characters), this new theatrical space began to accommodate the women actors for the representation of female characters. -

Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay

Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay drishtiias.com/printpdf/bankim-chandra-chattopadhyay Why in News Indian Prime Minister paid homage to Rishi Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay on his Jayanti on 27th June. Key Points About: He was one of the greatest novelists and poets of India. He was born on 27th June 1838 in the village of Kanthapura in the town of North 24 Parganas, Naihati, present day West Bengal. He composed the song Vande Mataram in Sanskrit, which was a source of inspiration to the people in their freedom struggle. In 1857, there was a strong revolt against the rule of East India Company but Bankim Chandra Chatterjee continued his studies and passed his B.A. Examination in 1859. The Lieutenant Governor of Calcutta appointed Bankim Chandra Chatterjee as Deputy Collector in the same year. He was in Government service for thirty-two years and retired in 1891. He died on 8th April, 1894. 1/2 Contributions to India’s Freedom Struggle: His epic Novel Anandamath - set in the background of the Sanyasi Rebellion (1770-1820), when Bengal was facing a famine too - made Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay an influential figure on the Bengali renaissance. He kept the people of Bengal intellectually stimulated through his literary campaign. India got its national song, Vande Mataram, from Anandamath. He also founded a monthly literary magazine, Bangadarshan, in 1872, through which Bankim is credited with influencing the emergence of a Bengali identity and nationalism. Bankim Chandra wanted the magazine to work as the medium of communication between the educated and the uneducated classes. The magazine stopped publication in the late 1880s, but was resurrected in 1901 with Rabindranath Tagore as its editor. -

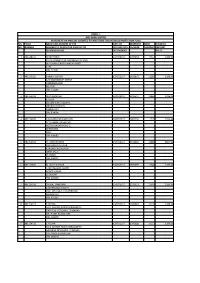

Srl Folio Name and Address of the Date of Warrant Micr Dividend No

FORM - I AXIS BANK LIMITED STATEMENT OF AMOUNT CREDITED TO INVESTORS' EDUCATION & PROTECTION FUND SRL FOLIO NAME AND ADDRESS OF THE DATE OF WARRANT MICR DIVIDEND NO. NUMBER MEMBER TO WHOM THE AMOUNT OF DECLARATION NUMBER NUMBER AMOUNT DIVIDEND IS DUE OF DIVIDEND (RS./-) 1 ABL148191 MANTA DEVI 13/07/2017 1905264 5713 1200.00 G V M CONVENT SR SECONDARY SCHOOL JAI PURWA GANDHI NAGAR BASTI (U P) PIN: 272001 2 ABL150181 SHIBANI GHOSH 13/07/2017 1911863 12285 1200.00 C/O BAIDYANATH GHOSH DEBENDRAGANJ BOLPUR PIN: 731204 3 ABL152443 ALKA PRAKASH 13/07/2017 1912547 12969 1296.00 E-355/II, SECTOR-2,HEC COLONY, DHURWA,RANCHI, JHARKHAND PIN: 834004 4 ABL153076 NIJANAND PATWARDHAN 13/07/2017 1901776 2225 2244.00 B-7,SUMAN SUDHA CHS, PESTOMSAGAR ROAD-5, CHEMBURA NULL PIN: 400089 5 ABL153592 R. JANAKIRAMAN 13/07/2017 1912663 13085 8604.00 192 GROUND FLOOR KARUMUTHU NILYAM ANNA SALAI CHENNAI PIN: 600002 6 ABL153845 M JAVED AKHTAR 13/07/2017 1905099 5548 1200.00 1/30 VISHWAS KHAND GOMTI NAGAR LUCKNOW PIN: 226010 7 ABL154335 PROBAL SANATANI 13/07/2017 1912521 12943 1200.00 SUBARNOSILA LALDIH POST GHATSILA E SINGHBHUM JHARKHAND PIN: 832303 8 ABL154713 C ROOPA 13/07/2017 1909687 10116 1200.00 NO 2 304 3RD FLOOR SHRAVANTHI GARDENS 15TH MAIN J P NAGAR 5TH PHASE BANGALORE PIN: 560078 9 ABL154716 C ROOPA 13/07/2017 1909688 10117 1200.00 NO 2 304 3RD FLOOR SHRAVANTHI GARDENS 15TH MAIN J P NAGAR 5TH PHASE BANGALORE PIN: 560078 AXIS BANK LIMITED STATEMENT OF AMOUNT CREDITED TO INVESTORS' EDUCATION & PROTECTION FUND SRL FOLIO NAME AND ADDRESS OF THE DATE OF WARRANT MICR DIVIDEND NO. -

Scott of Bengal”: Examining the European Legacy in the Historical Novels of Bankimchandra Chatterjee

“Scott of Bengal”: Examining the European Legacy in the Historical Novels of Bankimchandra Chatterjee Nilanjana Dutta A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department English and Comparative Literature Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by: Sucheta Mazumdar John McGowan Eric Downing Srinivas Aravamudan Tony Stewart ABSTRACT Nilanjana Dutta: “Scott of Bengal”: Examining the European Legacy in the Historical Novels of Bankimchandra Chatterjee (Under the direction of Sucheta Mazumdar) It is generally agreed that the novel is of European origin and that it was imported into non-European countries through colonial contact. While acknowledging this European precedence, it is important to also acknowledge the unique ways in which non- European authors indigenized the form to respond to the needs of their contemporary readers who were their intended audience. The works of the nineteenth-century Indian novelist Bankimchandra Chatterjee are a case in point. This dissertation focuses on the role the historical novels of Bankim performed in determining Indian identities at a particular juncture in Indian colonial history. A comparative study with selected novels of Sir Walter Scott, the premier historical novelist of Europe, helps illustrate the singularity of Bankim’s task; Scott and Bankim occupied quite different worlds and their works serve as metaphors of this difference. As the first successful novelist of India, Bankim took on the task of invoking history to create a national identity for a people who, he felt, did not have one. This identity had to be imagined through complex negotiations of race, religion, and gender, each of which required constant redefining. -

Bankim Chandra Vande Mataram Sujalam Sujhalam

Bankim Chandra Vande Mataram Sujalam Sujhalam Malayajasheetalam Sasyashyamalam Mataram II There is hardly an Indian who is not familiar with this National Song. Possibly, most of us do not know who composed this song. Bankim ChandraChatterjee wrote many novels. One of them is 'Anandamatha'. This novel contains a thrilling account of a struggle for freedom. Vande Mataram' appears as a part of this novel. Bankim Chandra Chatterjee was born on 27th June 1838 in the village Kantalpara of the Twenty-four Paraganas District of Bengal. He belonged to a family of Brahmins. The family was well known for the performance of yagas (sacrifices). Bankim Chandra's father Yadav Chandra Chattopadhyaya was in government service. In the very year of his son's birth he went to Midnapur as Deputy Collector. Bankim Chandra's mother was a Pious, good and affectionate lady. Page 1 of 20 Bankim Chandra The word 'Bankim Chandra' means in Bengali 'the moon on the second day of the bright fortnight'. The moon in the bright half of the month grows and fills out day by day. Bankim Chandra's parents probably wished that the honor of their family should grow from strength to strength through this child, and therefore called him Bankim Chandra. Bankim Chandra's education began in Midnapur. Even as a boy he was exceptionally brilliant. He learnt the entire alphabet in one day. Elders wondered at this marvel. For long time Bankim Chandra's intelligence was the talk of the town. Whenever they came across a very intelligent student, teachers of Midnapur would exclaim, "Ah, there is another Bankim Chandra in the making". -

Unit 1 the Contexts of Bankim

UNIT 1 THE CONTEXTS OF BANKIM Structure Objectives Introduction Bankim's Literary Context Bankim's Life and Views Bankim's Early Concerns 1.4.1 Eankirn's Later Themes Bankim's Age and Social Ethos Bankim's Other Works Let Us Sum Up Questions Glossary 1.0 OBJECTIVES Over tliis unit and the next one, we will try to locate Bankim within his contexts. It f must be understood here that no writer can write in a vacuum, that each writer is shaped by a whole.range of factors: the age she/he wrote in, the class into which they were born, the literary and social issues that they were concerned about and the manner in which it shaped their work. We will begin by looking at Bankimb literary context and see his shaping as a writer -we will look at his early and lqtet cqncerns, his age and the social ethos of the time. And then, in the second part we will see how Bankim changed, how and why he repudiated early writings and how finally liis political ideas became controversial and --- ' 1.1 INTRODUCTION -- - -- - - Firstly, we will look at the time ofthe Bengal Renaissance -the rich and varied literature that-emerged from Bengal and the early precursors to the novel as it finally emerged. It is important to see the literary history of the time because Bankim's works must be seen historically as the pioneering works that they were. His novels are the first accomplished realist narratives that we have. The concern with issues of middle class life, the centrality of women, the moral conflicts at the heart of his narratives are all features of his work that gave him the unique position he holds. -

(Re-)Imagining the Nation: the Indian Historical Novel in English, 1900-2000

Negotiating History, (Re-)imagining the Nation: The Indian Historical Novel in English, 1900-2000 by Md. Rezaul Haque Master of Arts in Applied Linguistics (The University of Sydney, 2004) Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English, Creative Writing and Australian Studies Flinders University, South Australia June 2013 1 Table of Contents Introduction (6-45) Chapter 1 (46-92) Fiction, History and Nation in India Chapter 2 (93-137) The Emergence of Indian Historical Fiction: The Colonial Context Chapter 3 (138-162) Revivalist Historical Fiction 1: Padmini: An Indian Romance (1903) Chapter 4 (163-205) Revivalist Historical Fiction 2: Nur Jahan: The Romance of an Indian Queen (1909) Chapter 5 (206-241) Nationalist History Fiction 1: Kanthapura (1938) Chapter 6 (242-287) Nationalist History Fiction 2: The Lalu Trilogy (1939-42) Chapter 7 (288-351) Feminist History Fiction: Some Inner Fury (1955) Chapter 8 (352-391) Interventionist History Fiction: The Shadow Lines (1988) Chapter 9 (392-436) Revisionist Historical Fiction: The Devil’s Wind (1972) Conclusion (437-446) Bibliography (447-468) 2 Thesis Summary As the title of my project suggests, this thesis deals with Indian historical fiction in English. While the time frame in the title may lead one to expect that the present study will attempt a historical overview of the Indian historical novel written in English, that is not a primary concern. Rather, I pose two broad questions: the first asks, to what uses does Indian English fiction put the Indian past as it is remembered in both formal history and communal memory? The second question is perhaps a more important one so far as this project is concerned: why does the Indian English novel use the Indian past in the ways that it does? There is as a consequence an intention to move from the inner world of Indian historical fiction to the outer space of the socio-political reality from which the novel under consideration has been produced. -

HINDUS and MUSLIMS in the NOVELS of BANKIM CHANDRA CHATTERJEE Author(S): Ranjana Das and Ranjan Das Source: Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol

THE NATION AND THE COMMUNITY: HINDUS AND MUSLIMS IN THE NOVELS OF BANKIM CHANDRA CHATTERJEE Author(s): Ranjana Das and Ranjan Das Source: Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 73 (2012), pp. 578-587 Published by: Indian History Congress Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44156251 Accessed: 06-04-2020 06:42 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Indian History Congress is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Proceedings of the Indian History Congress This content downloaded from 27.61.123.5 on Mon, 06 Apr 2020 06:42:25 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms THE NATION AND THE COMMUNITY: HINDUS AND MUSLIMS IN THE NOVELS OF BANKIM CHANDRA CHATTERJEE Ranjana Das Cultural encounter with the colonial state gave rise to reconstructive processes that allowed the subject intellectual class in nineteenth century Bengal to engage in discourses of 'self' representation. These discourses were inherently complex as they strove for an autonomous understanding of their past but largely remained within the colonial paradigm. From reform to revival, from liberal to conservative movements the debate according to David Kopf was between 'two Orientalist derived re-interpretations of the Indian heritage'.1 Partha Chatterjee however, provides them a degree of autonomy and argues that the first efforts of nationalist imaginations were made in the spiritual-cultural domain which inhered the essence of an indigenous cultural identity and which had to be preserved and protected from Western encroachments.