Rajmohan's Wife

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Imperial and the Colonized Women's Viewing of the 'Other'

Gazing across the Divide in the Days of the Raj: The Imperial and the Colonized Women’s Viewing of the ‘Other’ Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Vorgelegt von Sukla Chatterjee Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Hans Harder Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Benjamin Zachariah Heidelberg, 01.04.2016 Abstract This project investigates the crucial moment of social transformation of the colonized Bengali society in the nineteenth century, when Bengali women and their bodies were being used as the site of interaction for colonial, social, political, and cultural forces, subsequently giving birth to the ‘new woman.’ What did the ‘new woman’ think about themselves, their colonial counterparts, and where did they see themselves in the newly reordered Bengali society, are some of the crucial questions this thesis answers. Both colonial and colonized women have been secondary stakeholders of colonialism and due to the power asymmetry, colonial woman have found themselves in a relatively advantageous position to form perspectives and generate voluminous discourse on the colonized women. The research uses that as the point of departure and tries to shed light on the other side of the divide, where Bengali women use the residual freedom and colonial reforms to hone their gaze and form their perspectives on their western counterparts. Each chapter of the thesis deals with a particular aspect of the colonized women’s literary representation of the ‘other’. The first chapter on Krishnabhabini Das’ travelogue, A Bengali Woman in England (1885), makes a comparative ethnographic analysis of Bengal and England, to provide the recipe for a utopian society, which Bengal should strive to become. -

Equality (Samya)

Equality (Samya) Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay Classics Revisited Equality (Samya) Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay Translated by Bibek Debroy Liberty Institute New Delhi © 2002 LIBERTY INSTITUTE, New Delhi All rights including the right to translate or to reproduce this book or parts thereof except for brief quotations, are reserved. Rs 100 or US$ 5 PRINTED IN INDIA Published by: Liberty Institute E-6, Press Apartments, Patparganj Delhi-110092, India Tel.: 91-11-26528244, E-mail: [email protected] Contents Preface—Barun S. Mitra 7 Chapter 1 11 Chapter 2 22 Chapter 3 32 Chapter 4 42 Chapter 5 54 Conclusion 69 Bengali Wordnote 70 Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay (1838-1898) Preface We are very pleased to publish this English translation of Samya ~ Equality, which is one of the lesser known essays of Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay, the 19th Century Bengali author. In 1882, Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay (1838-1898) published the historical novel Anandamath containing his most famous verse and created a wave. The resounding echo of ‘Vande Mataram’ (Glory to Motherland) could be heard from young nationalist heroes headed for the gallows, leaders who addressed political rallies and barefoot children running the streets. More than a hundred years later, in 2002, this ‘second national anthem’ is being sung in school prayer halls and by fervent Hindu revivalists. However, if we accord to Bankimchandra the brand of nationalism that Vande Mataram has come to signify today, we’d be telling only half the story. The 19th century author who lived in the heydays of the intellectual revolution in Bengal ranks high amongst the historical figures who have contributed to the notions of liberalism and freedom. -

Actresses on Bengali Stage—Nati Binodini and Moyna: the Present Re-Imagines the Past

Actresses on Bengali Stage—Nati Binodini and Moyna: the Present Re-imagines the Past Madhumita Roy and Debmalya Das. Visva Bharati, Santiniketan. India. Abstract The Bengal Renaissance ushered in the process of multifaceted modernization resulting in the major reshaping of the theatrical space both in terms of convention and praxis. Abandoning the convention of cross–dressing (where the earlier male actors were dressed as women to represent female characters), this new theatrical space began to accommodate the women actors for the representation of female characters. Parallel with the emergence of the “New Woman” in the upper middle class society of the nineteenth century, the women actors also constituted a segregated sphere of the emancipated women. Although “free” to encounter the public sphere, they were denied the degree of social acceptability/status that was otherwise available to the then upper middle class “New Women.” This paper tries to locate the experience of a female actor of nineteenth century: Binodini Dasi: as is rendered in her two short autobiographical writings and the re-imagination of that experience in the twentieth century play Tiner Taloar by Utpal Dutt. Dutt uses the historical material to explore the consolidation and redefinition of the feminine space in his contemporary theatre. [Keywords: theatre, actress, performance, prostitution, protest, commodification, liberty.] The Bengal Renaissance ushered in the process of multifaceted modernization resulting in the major reshaping of the theatrical space both in terms of convention and praxis. Abandoning the convention of cross–dressing (whereas the earlier male actors were dressed as women to represent female characters), this new theatrical space began to accommodate the women actors for the representation of female characters. -

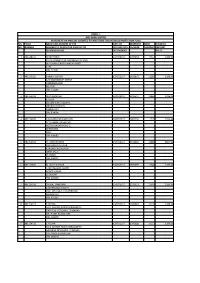

Srl Folio Name and Address of the Date of Warrant Micr Dividend No

FORM - I AXIS BANK LIMITED STATEMENT OF AMOUNT CREDITED TO INVESTORS' EDUCATION & PROTECTION FUND SRL FOLIO NAME AND ADDRESS OF THE DATE OF WARRANT MICR DIVIDEND NO. NUMBER MEMBER TO WHOM THE AMOUNT OF DECLARATION NUMBER NUMBER AMOUNT DIVIDEND IS DUE OF DIVIDEND (RS./-) 1 ABL148191 MANTA DEVI 13/07/2017 1905264 5713 1200.00 G V M CONVENT SR SECONDARY SCHOOL JAI PURWA GANDHI NAGAR BASTI (U P) PIN: 272001 2 ABL150181 SHIBANI GHOSH 13/07/2017 1911863 12285 1200.00 C/O BAIDYANATH GHOSH DEBENDRAGANJ BOLPUR PIN: 731204 3 ABL152443 ALKA PRAKASH 13/07/2017 1912547 12969 1296.00 E-355/II, SECTOR-2,HEC COLONY, DHURWA,RANCHI, JHARKHAND PIN: 834004 4 ABL153076 NIJANAND PATWARDHAN 13/07/2017 1901776 2225 2244.00 B-7,SUMAN SUDHA CHS, PESTOMSAGAR ROAD-5, CHEMBURA NULL PIN: 400089 5 ABL153592 R. JANAKIRAMAN 13/07/2017 1912663 13085 8604.00 192 GROUND FLOOR KARUMUTHU NILYAM ANNA SALAI CHENNAI PIN: 600002 6 ABL153845 M JAVED AKHTAR 13/07/2017 1905099 5548 1200.00 1/30 VISHWAS KHAND GOMTI NAGAR LUCKNOW PIN: 226010 7 ABL154335 PROBAL SANATANI 13/07/2017 1912521 12943 1200.00 SUBARNOSILA LALDIH POST GHATSILA E SINGHBHUM JHARKHAND PIN: 832303 8 ABL154713 C ROOPA 13/07/2017 1909687 10116 1200.00 NO 2 304 3RD FLOOR SHRAVANTHI GARDENS 15TH MAIN J P NAGAR 5TH PHASE BANGALORE PIN: 560078 9 ABL154716 C ROOPA 13/07/2017 1909688 10117 1200.00 NO 2 304 3RD FLOOR SHRAVANTHI GARDENS 15TH MAIN J P NAGAR 5TH PHASE BANGALORE PIN: 560078 AXIS BANK LIMITED STATEMENT OF AMOUNT CREDITED TO INVESTORS' EDUCATION & PROTECTION FUND SRL FOLIO NAME AND ADDRESS OF THE DATE OF WARRANT MICR DIVIDEND NO. -

Scott of Bengal”: Examining the European Legacy in the Historical Novels of Bankimchandra Chatterjee

“Scott of Bengal”: Examining the European Legacy in the Historical Novels of Bankimchandra Chatterjee Nilanjana Dutta A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department English and Comparative Literature Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by: Sucheta Mazumdar John McGowan Eric Downing Srinivas Aravamudan Tony Stewart ABSTRACT Nilanjana Dutta: “Scott of Bengal”: Examining the European Legacy in the Historical Novels of Bankimchandra Chatterjee (Under the direction of Sucheta Mazumdar) It is generally agreed that the novel is of European origin and that it was imported into non-European countries through colonial contact. While acknowledging this European precedence, it is important to also acknowledge the unique ways in which non- European authors indigenized the form to respond to the needs of their contemporary readers who were their intended audience. The works of the nineteenth-century Indian novelist Bankimchandra Chatterjee are a case in point. This dissertation focuses on the role the historical novels of Bankim performed in determining Indian identities at a particular juncture in Indian colonial history. A comparative study with selected novels of Sir Walter Scott, the premier historical novelist of Europe, helps illustrate the singularity of Bankim’s task; Scott and Bankim occupied quite different worlds and their works serve as metaphors of this difference. As the first successful novelist of India, Bankim took on the task of invoking history to create a national identity for a people who, he felt, did not have one. This identity had to be imagined through complex negotiations of race, religion, and gender, each of which required constant redefining. -

Unit 1 the Contexts of Bankim

UNIT 1 THE CONTEXTS OF BANKIM Structure Objectives Introduction Bankim's Literary Context Bankim's Life and Views Bankim's Early Concerns 1.4.1 Eankirn's Later Themes Bankim's Age and Social Ethos Bankim's Other Works Let Us Sum Up Questions Glossary 1.0 OBJECTIVES Over tliis unit and the next one, we will try to locate Bankim within his contexts. It f must be understood here that no writer can write in a vacuum, that each writer is shaped by a whole.range of factors: the age she/he wrote in, the class into which they were born, the literary and social issues that they were concerned about and the manner in which it shaped their work. We will begin by looking at Bankimb literary context and see his shaping as a writer -we will look at his early and lqtet cqncerns, his age and the social ethos of the time. And then, in the second part we will see how Bankim changed, how and why he repudiated early writings and how finally liis political ideas became controversial and --- ' 1.1 INTRODUCTION -- - -- - - Firstly, we will look at the time ofthe Bengal Renaissance -the rich and varied literature that-emerged from Bengal and the early precursors to the novel as it finally emerged. It is important to see the literary history of the time because Bankim's works must be seen historically as the pioneering works that they were. His novels are the first accomplished realist narratives that we have. The concern with issues of middle class life, the centrality of women, the moral conflicts at the heart of his narratives are all features of his work that gave him the unique position he holds. -

(Re-)Imagining the Nation: the Indian Historical Novel in English, 1900-2000

Negotiating History, (Re-)imagining the Nation: The Indian Historical Novel in English, 1900-2000 by Md. Rezaul Haque Master of Arts in Applied Linguistics (The University of Sydney, 2004) Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English, Creative Writing and Australian Studies Flinders University, South Australia June 2013 1 Table of Contents Introduction (6-45) Chapter 1 (46-92) Fiction, History and Nation in India Chapter 2 (93-137) The Emergence of Indian Historical Fiction: The Colonial Context Chapter 3 (138-162) Revivalist Historical Fiction 1: Padmini: An Indian Romance (1903) Chapter 4 (163-205) Revivalist Historical Fiction 2: Nur Jahan: The Romance of an Indian Queen (1909) Chapter 5 (206-241) Nationalist History Fiction 1: Kanthapura (1938) Chapter 6 (242-287) Nationalist History Fiction 2: The Lalu Trilogy (1939-42) Chapter 7 (288-351) Feminist History Fiction: Some Inner Fury (1955) Chapter 8 (352-391) Interventionist History Fiction: The Shadow Lines (1988) Chapter 9 (392-436) Revisionist Historical Fiction: The Devil’s Wind (1972) Conclusion (437-446) Bibliography (447-468) 2 Thesis Summary As the title of my project suggests, this thesis deals with Indian historical fiction in English. While the time frame in the title may lead one to expect that the present study will attempt a historical overview of the Indian historical novel written in English, that is not a primary concern. Rather, I pose two broad questions: the first asks, to what uses does Indian English fiction put the Indian past as it is remembered in both formal history and communal memory? The second question is perhaps a more important one so far as this project is concerned: why does the Indian English novel use the Indian past in the ways that it does? There is as a consequence an intention to move from the inner world of Indian historical fiction to the outer space of the socio-political reality from which the novel under consideration has been produced. -

HINDUS and MUSLIMS in the NOVELS of BANKIM CHANDRA CHATTERJEE Author(S): Ranjana Das and Ranjan Das Source: Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol

THE NATION AND THE COMMUNITY: HINDUS AND MUSLIMS IN THE NOVELS OF BANKIM CHANDRA CHATTERJEE Author(s): Ranjana Das and Ranjan Das Source: Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 73 (2012), pp. 578-587 Published by: Indian History Congress Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44156251 Accessed: 06-04-2020 06:42 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Indian History Congress is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Proceedings of the Indian History Congress This content downloaded from 27.61.123.5 on Mon, 06 Apr 2020 06:42:25 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms THE NATION AND THE COMMUNITY: HINDUS AND MUSLIMS IN THE NOVELS OF BANKIM CHANDRA CHATTERJEE Ranjana Das Cultural encounter with the colonial state gave rise to reconstructive processes that allowed the subject intellectual class in nineteenth century Bengal to engage in discourses of 'self' representation. These discourses were inherently complex as they strove for an autonomous understanding of their past but largely remained within the colonial paradigm. From reform to revival, from liberal to conservative movements the debate according to David Kopf was between 'two Orientalist derived re-interpretations of the Indian heritage'.1 Partha Chatterjee however, provides them a degree of autonomy and argues that the first efforts of nationalist imaginations were made in the spiritual-cultural domain which inhered the essence of an indigenous cultural identity and which had to be preserved and protected from Western encroachments. -

Wives and Widows in Bankim Chandra Chatterjee's Novels

International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume 3, Issue 12, December 2013 1 ISSN 2250-3153 Wives and Widows in Bankim Chandra Chatterjee’s Novels Anuma Student of PhD in Department of English University of Rajasthan The topic which I have taken for my term paper is about the depiction of wives and widows in Bankim Chandra Chatterjee’s novels Krishnakanta’s will, Bishabriksha, Devi Chaudhrani and Indira. I am mainly focusing on the way how Bankim is writing about the condition of women in contemporary Bengali society and at the same time also describing the conflict between their personal desires and social expectations. Bankim Chandra Chatterjee also known as Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, was one of the greatest novelists and poets of India. He is famous as author of Vande Mataram, the national song of India. Bankim Chandra Chatterjee began his literary career as a writer of verse. He then turned to fiction. Durgeshnandini, his first Bengali romance, was published in 1865. His famous novels include Kapalkundala (1866), Mrinalini (1869), Vishbriksha (1873), Chandrasekhar (1877), Rajani (1877), Rajsinha (1881), and Devi Chaudhurani (1884). Bankim Chandra Chatterjee most famous novel was Anand Math (1882). Anand Math contained the song "Bande Mataram", which was later adopted as National Song. Bankim Chandra Chatterjee wanted to bring about a cultural revival of Bengal by stimulating the intellect of the Bengali speaking people through literary campaign. With this end in view he brought out monthly magazine called Bangadarshan in 1872. Bankim Chandra Chatterjee was the first to introduce the pre-marital romance in his novels in Bengali literature and which was completely in opposition of the male-dominated orthodox society of that time. -

Rare Collections of Some Old Public Libraries in Kolkata: a Comparative Study

Rare Collections of Some Old Public Libraries in Kolkata: A Comparative Study Jahir Uddin Molla Librarian Chandpara Bani Vidya Bithi West Bangal- India [email protected] Dr. Biswajit Das University Librarian The University of Gour Banga West Bangal- India Abstract: Libraries do not only spread knowledge, they are the time capsules which conserve historical and rare pieces of literature and work and are actively involved in the conservation and enhancement of the heritage of humanity. Libraries also point people to wider cultural activities, objects, knowledge and sites, and encourage individuals to explore different cultural experiences and to create things themselves. For all the bibliophiles, out there, here is a list of 6 libraries in Kolkata with amazing collection to quench your thirst for reading. Keywords: Old and rare collections, Library services, Archives, Collections, Collection management, Manuscripts, History, Oriental Libraries Introduction: Public libraries, the local gateways to knowledge, provide basic conditions for lifelong learning, independent decisionmaking and cultural development of the individual and social groups. They are developed out of public funds and the use of these is not restricted to any class of persons in the community. These are the local centres of information, making all kinds of knowledge and information readily available to its users. According to U NESCO in Public Library Manifesto (1994), the missions of public libraries are: Creating and strengthening reading habits in children from an early age Supporting individual both formal education as well as self conducted education at all level Providing opportunities for personal creative development Stimulating the imagination and creativity of children and young people Promoting awareness of cultural heritage, appreciation of the arts, scientific achievements and innovations Ensuring access for citizens to all sorts of community information etc. -

The Birth of the Novel in Nineteenth- Century Bengal

DEAR READER, GOOD SIR: THE BIRTH OF THE NOVEL IN NINETEENTH- CENTURY BENGAL by SUNAYANI BHATTACHARYA A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Comparative Literature and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2017 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Sunayani Bhattacharya Title: Dear Reader, Good Sir: The Birth of the Novel in Nineteenth-Century Bengal This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of Comparative Literature by: Sangita Gopal Chairperson Paul Peppis Core Member Michael Allan Core Member Naomi Zack Institutional Representative and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded March 2017 ii © 2017 Sunayani Bhattacharya iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Sunayani Bhattacharya Doctor of Philosophy Department of Comparative Literature March 2017 Title: Dear Reader, Good Sir: The Birth of the Novel in Nineteenth-Century Bengal My dissertation traces the formation and growth of the reader of the Bengali novel in nineteenth century Bengal through a close study of the writings by Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay that comment on—and respond to—both the reader and the newly emergent genre of the Bengali novel. In particular, I focus on the following texts: two novels written by Bankim, Durgeśnandinī (The Lady of the Castle ) (1865) and Bishabṛksha (The Poison Tree ) (1872), literary essays published in nineteenth century Bengali periodicals, personal letters written by Bankim and his contemporaries, and reviews of the novels, often written and published anonymously. -

Journal of the Asiatic Society

Pandit Iswarchandra Vidyasagar by France Bhattacharya 1000 Sarvadarshana Samgraha with English translation by E. B. Cowell & A. E. Gough, ed. by Pandita Iswarachandra Vidyasagara 1000 Vidyasagar : Ekush Sataker Chokhey ed. by Pallab Sengupta & Amita Chakraborty 200 Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya and Lokayata ed. by Dilipkumar Mohanta 450 Consequence of Ageing in a Tribal Society and its Cultural Age Construct by Saumitra Basu 480 Ethnography, Historiography and North-East India by H. Sudhir 500 Vidyasagar (Jibancharit) of Chandi Charan Bandyopadhyay translated into Hindi by Rupnarayan Pandey 1000 The Joint Secretary Wings of Life ed. by Asok Kanti Sanyal 1000 Emergence of Castes and Outcastes : Historical Roots of the ‘Dalit’ Problem by Suvira Jaiswal 200 Food and Nutrition in Health & Disease ed. by Sukta Das 250 The Joint Secretary Pandit Iswarchandra Vidyasagar by France Bhattacharya 1000 Sarvadarshana Samgraha with English translation by E. B. Cowell & A. E. Gough, ed. by Pandita Iswarachandra Vidyasagara 1000 Vidyasagar : Ekush Sataker Chokhey ed. by Pallab Sengupta & Amita Chakraborty 200 Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya and Lokayata ed. by Dilipkumar Mohanta 450 Consequence of Ageing in a Tribal Society and its Cultural Age Construct by Saumitra Basu 480 Ethnography, Historiography and North-East India by H. Sudhir 500 Vidyasagar (Jibancharit) of Chandi Charan Bandyopadhyay translated into Hindi by Rupnarayan Pandey 1000 The Joint Secretary Wings of Life ed. by Asok Kanti Sanyal 1000 Emergence of Castes and Outcastes : Historical Roots of the ‘Dalit’ Problem by Suvira Jaiswal 200 Food and Nutrition in Health & Disease ed. by Sukta Das 250 JOURNAL OF THE ASIATIC SOCIETY VOLUME LXI No. 4 2019 THE ASIATIC SOCIETY 1 PARK STREET KOLKATA © The Asiatic Society ISSN 0368-3308 Edited and published by Dr.