Saul Lieberman and the Orthodox Part 2 Sources (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of Bibliographic References to Talmudic Literature

H-Judaic Internet Resource: Index of Bibliographic References to Talmudic Literature Discussion published by Moshe Feifer on Thursday, March 19, 2015 THE SAUL LIEBERMAN INSTITUTE OF TALMUDIC RESEARCH THE JEWISH THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY The Index of Bibliographic References to Talmudic Literature We are pleased to announce that the Lieberman Institute'sIndex of References Dealing with Talmudic Literature is available at http://lieberman-index.org. Introduction What is the Index? The Index is a comprehensive online research tool directing the user to discussions and interpretations of Talmudic passages found in both modern academic research and medieval Talmudic scholarship (Geonim and Rishonim). By clicking any Talmudic passage, the user will receive a list of specific books and page numbers within them discussing the selected passage. The Index is revolutionizing Talmudic research by supplying scholars with quick and easy access to pertinent information. Preceding the establishment of the index project, the task of finding specific bibliographical references that today takes minutes would take many hours or even days of work. The Index radically alters old methods of bibliographical searching and brings Talmudic research up to par with contemporary standards. In addition to those involved in Talmudic studies per se, the index is a vital aid to those engaged in all Judaic, ancient near east, or comparative religion studies to the extent that they relate at times to Talmudic texts. Thus, the database already makes an extremely significant contribution to all associated fields of research and study by enabling scholars, students or lay audience to quickly and comprehensively access relevant scholarship. Description Citation: Moshe Feifer. -

Marc Hirshman

THE TIKVAH CENTER FOR LAW & JEWISH CIVILIZATION Professor Moshe Halbertal Professor J.H.H. Weiler Directors of The Tikvah Center Tikvah Working Paper 07/12 Marc Hirshman Individual and Group Learning in Rabbinic Literature: Some Key Terms NYU School of Law • New York, NY 10011 The Tikvah Center Working Paper Series can be found at http://www.nyutikvah.org/publications.html All rights reserved. No part of this paper may be reproduced in any form without permission of the author. ISSN 2160‐8229 (print) ISSN 2160‐8253 (online) Copy Editor: Danielle Leeds Kim © Marc Hirshman 2012 New York University School of Law New York, NY 10011 USA Publications in the Series should be cited as: AUTHOR, TITLE, TIKVAH CENTER WORKING PAPER NO./YEAR [URL] Individual and Group Learning in Rabbinic Literature INDIVIDUAL AND GROUP LEARNING IN RABBINIC LITERATURE: SOME KEY TERMS By Marc Hirshman A. Foundations of Education in Biblical and Second Temple Times Wilhelm Bacher, the great late 19th, early 20th scholar, published in 1903 a wonderful essay entitled " Das altjüdische Schulewesen", in which he declared Nehemiah 8, 1-8, which describes the public reading of scripture, " der Geburtstag des altjüdischen Schulweis". From that day on 1 Tishre 445 b.c.e, Bacher would have it, the public recitation of Torah and its teaching would become central to second Temple Judaism, and its rabbinic heirs in the first five centuries of the common era. Indeed, Ezra's commission from Artaxerxes includes appointments of "judges and magistrates to judge all the people… and to teach…" (Ezra 7, 25). This close connection between the judicial system and the educational system also characterizes the rabbinic period, succinctly captured in the opening quote of the tractate of Avot 1,1. -

The Genius and Limitations of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik Z"L

The Genius and Limitations of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik z"l Byline: Rabbi Dr. Nathan Lopes Cardozo is Dean of the David Cardozo Academy in Jerusalem. Thoughts to Ponder 529 The Genius and Limitations of Rabbi Joseph Ber Soloveitchik z”l * Nathan Lopes Cardozo Based on an introduction to a discussion between Professor William Kolbrener and Professor Elliott Malamet (1) Honoring the publication of Professor William Kolbrener’s new book “The Last Rabbi” (2) Yad Harav Nissim, Jerusalem, on Feb. 1, 2017 Dear Friends, I never had the privilege of meeting Rav Soloveitchik z”l or learning under him. But I believe I have read all of his books on Jewish philosophy and Halacha, and even some of his Talmudic novellae and halachic decisions. I have also spoken with many of his students. Here are my impressions. No doubt Rav Soloveitchik was a Gadol Ha-dor (a great sage of his generation). He was a supreme Talmudist and certainly one of the greatest religious thinkers of our time. His literary output is incredible. Still, I believe that he was not a mechadesh – a man whose novel ideas really moved the Jewish tradition forward, especially regarding Halacha. He did not solve major halachic problems. This may sound strange, because almost no one has written as many novel ideas about Halacha as Rav Soloveitchik (3). His masterpiece, Halakhic Man, is perhaps the prime example. Before Rav Soloveitchik appeared on the scene, nobody – surely not in mainstream Orthodoxy – had seriously dealt with the ideology and philosophy of Halacha (4). Page 1 In fact, the reverse is true. -

Politics of Exclusion in Judaism

Politics of Exclusion in Judaism Saul Lieberman and the Orthodox Part 3 In 1959 Lieberman became rector of the Seminary, and one of his responsibilities was "guiding the general religious policy of the institution." Thus, there is certainly justice in the assertion that, whatever his personal religious commitments, Lieberman had become part and parcel of the Conservative movement and was assisting it at the time that the Orthodox were attempting to expose what they regarded as the Conservative's distortions of halakha. Furthermore, there is no question that the leaders of Conservativism were able to use the presence of Lieberman at the Seminary to help legitimize the institution when it was challenged on religious grounds. For example, when Chief Rabbi Herzog came to New York he was willing to meet with some members of the Seminary faculty, but would not enter the building because Kaplan worked there. Finkelstein recalled telling Herzog, "It can't be as bad as you think if [Saul] Lieberman sits on the faculty." The presence of Kaplan at the Seminary was one of many problems mentioned in the following nasty letter Lieberman received: Dear Sir, For the sake of Parnasah and glory you have sold yourself to the Sitra Achra [the other side]. Do you not know that you are lending prestige to Mordecai Kaplan (Yimach Shemo) and to the other Kofrim at the Seminary, as well as to the graduates who are almost in every case M'gulche-Taar and Boale-Niddah? The United States has many Rabbinical Schools where honest young men are studying Torah and developing Talmide-Chachamim. -

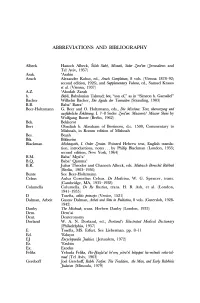

Abbreviations and Bibliography

ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY Albeck Hanoch Albeck, Sifah Sidre, Misnah, Seder Zera'im (Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, 1957) Arak. 'Arakin Aruch Alexander Kohut, ed., Aruch Completum, 8 vols. (Vienna 1878-92; second edition, 1926), and Supplementary Volume, ed., Samuel Krauss et al. (Vienna, 193 7) A.Z. 'Abodah Zarah b. Babli, Babylonian Talmud; ben, "son of," as in "Simeon b. Gamaliel" Bacher Wilhelm Bacher, Die Agada der Tannaiten (Strassling, 1903) B.B. Baba' Batra' Beer-Holtzmann G. Beer and 0. Holtzmann, eds., Die Mischna: Text, iiberset::;ung und ausfiihrliche Erkliirung, I. 7-8 Seder Zera'im: Maaserotl Mauser Sheni by Wolfgang Bunte (Berlin, 1962) Bek. Bekhorot Bert Obadiah b. Abraham of Bertinoro, d.c. 1500, Commentary to Mishnah, in Romm edition of Mishnah Bes. Be~ah Bik. Bikkurim Blackman Mishnayoth, I. Order Zeraim. Pointed Hebrew text, English transla tion, introductions, notes ... by Philip Blackman (London, 1955; second edition, New York, 1964) B.M. Baba' Mesi'a' B.Q Baba' Qamma' B.R. Julius Theodor and Chanoch Albeck, eds. Midrasch Bereschit Rabbah (Berlin, 1903-1936) Bunte See Beer-Holtzmann Celsus Aulus Cornelius Celsus. De Medicina, W. G. Spencer, trans. (Cambridge, MA, 1935-1938) Columella Columella. De Re Rustica, trans. H. B. Ash, et al. (London, 1941-1955) D Tosefta, editio princeps (Venice, 1521) Dalman, Arbeit Gustav Dalman, Arbeit und Sitte in Paliistina, 8 vols. (Gutersloh, 1928- 1942) Danby The Mishnah, trans. Herbert Danby (London, 1933) Dem. Dem'ai Deut. Deuteronomy Dorland W. A. N. Dorland, ed., Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (Philadelphia, 195 7) E Tosefta, MS. Erfurt. See Lieberman. pp. 8-11 Ed. -

Qumran Yaḥad and Rabbinic Ḥăbûrâ

Dead Sea Discoveries 16 (2009) 433–453 brill.nl/dsd Qumran Yaḥad and Rabbinic Ḥăbûrâ: A Comparison Reconsidered1 Steven D. Fraade Department of Religious Studies, Yale University, P.O. Box 208287 451 College Street, New Haven, CT 06520-8287 [email protected] Abstract Since soon after the initial discoveries and publications of the Dead Sea Scrolls, scholars have compared the yahaḍ of the scrolls with the hạ bûrâ̆ of early rabbinic literature and sought to establish a historical relationship and developmental pro- gression between the two types of communal organization. Th e present article reviews select but representative examples from such scholarship, seeking to reveal their underlying presumptions and broader implications, while questioning whether the available evidence allows for the sorts of sociological comparisons and historical reconstructions that they adduce. Keywords Essenes, hạ bûrâ̆ , historiography, history of scholarship, Pharisees, rabbinic literature, yahaḍ 1. Introduction In the fi rst scholarly announcement of the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, William F. Albright, having seen only four scrolls, presciently wrote early in 1948: 1 Th is article began as a paper at the Society of Biblical Literature, 2007 Annual Meeting, San Diego, CA, November 18, 2007. I wish to acknowledge the gener- ous and sage assistance of the following colleagues in preparing this article for publication: John Collins, Yair Furstenberg, Yonder Gillihan, and Charlotte Hempel. © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2009 DOI: 10.1163/156851709X474012 434 S. D. Fraade / Dead Sea Discoveries 16 (2009) 433–453 It is easy to surmise that the new discovery will revolutionize intertes- tamental studies, and that it will soon antiquate all present handbooks on the background of the New Testament and on the textual criticism and interpretation of the Old Testament.2 Th e absence of any mention of early rabbinic literature as a fi eld that might be aff ected by the new-found scrolls was not a mere oversight. -

Saul Lieberman and the Orthodox Part 1 Sources (PDF)

Politics of Exclusion in Judaism Saul Lieberman and the Orthodox Part 1 Background 1. While it might have been possible to find an instructor in history from outside the Orthodox community, instructors in Talmud were much more difficult to locate. After all, where else but among the Orthodox did young men devote themselves to the study of rabbinic literature and rise to the level of experts, thus making them worth of training future rabbis? It is therefore no surprise that the various non-Orthodox seminaries looked to the Orthodox. These institutions were willing to respect the Orthodox faculty member's religious autonomy; that is, they would not force them to violate their religious principles. The assumption of the directors of these seminaries – soon to be proven correct – was that there would be members of the Orthodox scholarly elite who, for financial or perhaps even idealistic reasons, would be willing to instruct students at their institutions (Shapiro, 1). 2. It has always been easy for the Orthodox public at large to ignore those who teach at non-Orthodox seminaries, even if these men are completely observant…yet it is not so easy for Orthodox scholars to ignore their work. On the one hand, they are regarded as having cast their lot with the non-Orthodox; on the other hand, their work is often valuable even to the most close-minded of the Orthodox. The problem, therefore, presents itself: How should Orthodox scholars relate to those who teach at non-Orthodox seminaries. This is obviously not an issue that concerns those Orthodox who pursue academic Jewish studies, but is indeed relevant to those who are involved in traditional Talmud study. -

Two Women Who Were Sporting with Each Other": a Reexamination of the Halakhic Approaches to Lesbianism As a Touchstone for Homosexuality in General1

10 ADMIEL KOSMAN / ANAT SHARBAT "Two Women Who Were Sporting with Each Other": A Reexamination of the Halakhic Approaches to Lesbianism as a Touchstone for Homosexuality in General1 Admiel Kosman and Anat Sharbat I. Introduction A Modern Perspective for the Discussion Modern scholarly research places female homoeroticism within the general cate- gory of homosexuality, but the study of this phenomenon includes broad sub- categories, each of which is worthy of a separate discussion. The current article is limited to the attitude of the halakhah to sexual relations between women, and is not concerned with homosexual identity or single-sex emotional relationships. Although the homosexual sexual identity, in its modern sense, developed only in the nineteenth century, as was shown by Michel Foucault,2 the view that re- garded the homosexual act3 as particularly abominable and unnatural developed extremely early in the Judeo-Christian tradition.4 This article will examine the roots of this attitude in the Jewish halakhah. Yaron Ben-Naeh recently published an important article on male homosexu- ality in Jewish Ottoman society, with an extensive presentation of the late rab- binical sources that relate to the phenomenon, that was widespread among Jews in Muslim society, in which "attraction to members of the same sex was consid- ered [...] to be part of the inclusive and normal set of male modes of conduct."5 1 Dieser Artikel erschien zuvor unter dem Titel: "Two women who were sporting with each Other". A reexamination of the Halakhic approaches to Lesbianism as a touchstone for homo- sexuality in general. In: Hebrew Union College Annual (HUCA) 75, pp. -

Orthodox Objection to the Lieberman Clause Atara Kelman

Orthodox Objection to the Lieberman Clause Presented to the S. Daniel Abraham Honors Program in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Completion of the Program Stern College for Women Yeshiva University May 6, 2020 Atara Kelman Mentor: Rabbi Ezra Schwartz Acknowledgements נשמת כל חי תברך את שמך ה׳ אלוקינו בכל עת צרה וצוקה אין לנו מלך אלא אתה As I work on this project during the COVID-19 pandemic, I recognize that the stability that I have felt my whole life is a mirage, and that our vulnerability is ever present. At the same time, I understand that I am fortunate and blessed with good health, a caring family, and emotional and economic security. These feelings are more prominent during this time of crises, but have been the hallmark of my life. At the culmination of the Honors Program, I am appreciative for opportunities the Honors Program has provided for me, with both intensive academic classes and cultural opportunities. Stern College served as my base for two years of learning and growing, and for that I am grateful. Rabbi Ezra Schwartz served as my mentor for this project, after teaching me for the majority of my time in Stern College. I am indebted to him for his suggestions, references, and commitment to helping me learn. A large portion of my research was stimulated by conversations with Rabbi Saul Berman, whose insight and integrity is inspiring. Most of all, this would not have been possible without the help of my family. My interest in such a topic certainly grew from conversations at home, and my family serves as the best editorial board. -

A Heart of Many Chambers”: the Theological Hermeneutics of Legal Multivocality

Harvard Theological Review http://journals.cambridge.org/HTR Additional services for Harvard Theological Review: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here “A Heart of Many Chambers”: The Theological Hermeneutics of Legal Multivocality Steven D. Fraade Harvard Theological Review / Volume 108 / Issue 01 / January 2015, pp 113 - 128 DOI: 10.1017/S0017816015000061, Published online: 06 February 2015 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0017816015000061 How to cite this article: Steven D. Fraade (2015). “A Heart of Many Chambers”: The Theological Hermeneutics of Legal Multivocality. Harvard Theological Review, 108, pp 113-128 doi:10.1017/S0017816015000061 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/HTR, IP address: 132.66.25.46 on 25 Feb 2015 “A Heart of Many Chambers”: The Theological Hermeneutics of Legal Multivocality* Steven D. Fraade Yale University Introduction Given the multiplicity of legal interpretations and opinions, the question of the place of legal debate within early rabbinic literature of late antiquity—both as textual practice and as hermeneutical and legal theory—has occupied a particularly busy space within recent scholarship.1 This question centers on several issues of broad significance for the history of rabbinic Judaism and its literature: Does this phenomenon (if we can speak of it in the singular) represent a defining characteristic of rabbinic culture overall, or rather an aspect better attributed -

Shamma Friedman February 2004

Shamma Friedman February 2004 Academic Degrees B.A. – Phi Beta Kappa – University of Pennsylvania, 1958 B.H.L. – Gratz College, 1958 M.H.L. – Jewish Theological Seminary, 1960 Rabbi – JTS, 1964 Ph.D. – JTS, 1966 Appointments Instructor in Talmud, JTS 1964 Assistant Professor of Rabbinics, JTS, 1967 Associate Professor of Rabbinics, JTS, 1970 Member, Faculty Committee on the Library Acting Librarian, JTS, 1969 Visiting Senior Teaching Fellow in Talmud, Bar-Ilan University 1970-71 Director, JTS, Jerusalem Campus, 1973-74 Dean, JTS Jerusalem Campus, 1973-87 Associate Professor in Talmud, University of Tel Aviv, 1974-75 Professor of Talmud, JTS, 1975 Fellow, The Institute of Advanced Studies, The Hebrew University, 1975-76 Visiting Professor in Didactics of Talmud Instruction, The Hebrew University, 1978-80 Editor, Hebrew Publications, JTS, 1984-90 Founding Director, The Saul Lieberman Institute of Talmudic Research, JTS, 1985- Director, The Schocken Institute, 1987-90 Associate Provost JTS, 1988-90 Professor, Department of Talmud, Bar-Ilan University, 1991- Fellow, Hartman Institute, 1993-1995 Gerard Weinstock Visiting Professor of Jewish Literature, Harvard University, 1997 Distinguished Service Professor, JTS, 1997 Academic Teaching, The Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies, Jerusalem The Society for the Interpretation of the Talmud, Founder and Chairman, 1993- Visiting Professor at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Faculty of Law, 1999-00 Appointed to the Israel Academy of the Hebrew Language, 2001 Benjamin and Minna Reeves Professor of Talmud and Rabbinics, JTS, 2002. Publications Books and Monographs: 1. Commentary of R. Jonathan of Lunel on Bava Kamma with introduction and notes (Hebrew), Jewish Theological Seminary and Feldheim, New York and Jerusalem, 1969, lxxii & 400 pp. -

A Charming, Learned, Gay Litvak.”

Seforim blog) have already was born in Riga in 1909, was identified as Saul Lieberman. After famously fluent in Russian.) A CHARMING, studying at the Slobodka yeshiva Although the job in Washington (where he was ordained at the age that Berlin believed to be awaiting LEARNED, of eighteen), Lieberman completed him never materialized, he returned his MA at the Hebrew University in to the U.S. in early 1941 as a 1931 and married the former Judith “specialist attached to the British GAY LITVAK Berlin in the following year. By Press Service,” which was located at Elliott Horowitz 1940 Lieberman was in New York, Rockefeller Center. During his serving as Professor of Palestinian wartime years in New York, Berlin riting home to London Literature and Institutions at the met almost everyone worth meeting from Jerusalem on the Jewish Theological Seminary. and befriended many American Wfirst day of Rosh Jews, including Governor Herbert Hashanah 1934, Isaiah Berlin, who As fate would have it, the year 1940 Lehmann (“a very nice comfortable had recently become the first Jew also saw the arrival, albeit more man, like a little brown bear”) and elected to a fellowship at All Souls briefly, of Isaiah Berlin in the Rabbi Stephen Wise who headed College, provided his parents with a United States, to which he had both the Jewish Institute of long list of the people he had met sailed in the company of his (then) Religion (JIR) and the American during his first three days in the friend Guy Burgess, both of whom Jewish Congress. Of the latter, a Holy City.