Qumran Yaḥad and Rabbinic Ḥăbûrâ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of Bibliographic References to Talmudic Literature

H-Judaic Internet Resource: Index of Bibliographic References to Talmudic Literature Discussion published by Moshe Feifer on Thursday, March 19, 2015 THE SAUL LIEBERMAN INSTITUTE OF TALMUDIC RESEARCH THE JEWISH THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY The Index of Bibliographic References to Talmudic Literature We are pleased to announce that the Lieberman Institute'sIndex of References Dealing with Talmudic Literature is available at http://lieberman-index.org. Introduction What is the Index? The Index is a comprehensive online research tool directing the user to discussions and interpretations of Talmudic passages found in both modern academic research and medieval Talmudic scholarship (Geonim and Rishonim). By clicking any Talmudic passage, the user will receive a list of specific books and page numbers within them discussing the selected passage. The Index is revolutionizing Talmudic research by supplying scholars with quick and easy access to pertinent information. Preceding the establishment of the index project, the task of finding specific bibliographical references that today takes minutes would take many hours or even days of work. The Index radically alters old methods of bibliographical searching and brings Talmudic research up to par with contemporary standards. In addition to those involved in Talmudic studies per se, the index is a vital aid to those engaged in all Judaic, ancient near east, or comparative religion studies to the extent that they relate at times to Talmudic texts. Thus, the database already makes an extremely significant contribution to all associated fields of research and study by enabling scholars, students or lay audience to quickly and comprehensively access relevant scholarship. Description Citation: Moshe Feifer. -

Marc Hirshman

THE TIKVAH CENTER FOR LAW & JEWISH CIVILIZATION Professor Moshe Halbertal Professor J.H.H. Weiler Directors of The Tikvah Center Tikvah Working Paper 07/12 Marc Hirshman Individual and Group Learning in Rabbinic Literature: Some Key Terms NYU School of Law • New York, NY 10011 The Tikvah Center Working Paper Series can be found at http://www.nyutikvah.org/publications.html All rights reserved. No part of this paper may be reproduced in any form without permission of the author. ISSN 2160‐8229 (print) ISSN 2160‐8253 (online) Copy Editor: Danielle Leeds Kim © Marc Hirshman 2012 New York University School of Law New York, NY 10011 USA Publications in the Series should be cited as: AUTHOR, TITLE, TIKVAH CENTER WORKING PAPER NO./YEAR [URL] Individual and Group Learning in Rabbinic Literature INDIVIDUAL AND GROUP LEARNING IN RABBINIC LITERATURE: SOME KEY TERMS By Marc Hirshman A. Foundations of Education in Biblical and Second Temple Times Wilhelm Bacher, the great late 19th, early 20th scholar, published in 1903 a wonderful essay entitled " Das altjüdische Schulewesen", in which he declared Nehemiah 8, 1-8, which describes the public reading of scripture, " der Geburtstag des altjüdischen Schulweis". From that day on 1 Tishre 445 b.c.e, Bacher would have it, the public recitation of Torah and its teaching would become central to second Temple Judaism, and its rabbinic heirs in the first five centuries of the common era. Indeed, Ezra's commission from Artaxerxes includes appointments of "judges and magistrates to judge all the people… and to teach…" (Ezra 7, 25). This close connection between the judicial system and the educational system also characterizes the rabbinic period, succinctly captured in the opening quote of the tractate of Avot 1,1. -

The Dead Sea Scrolls

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Maxwell Institute Publications 2000 The eD ad Sea Scrolls: Questions and Responses for Latter-day Saints Donald W. Parry Stephen D. Ricks Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/mi Part of the Religious Education Commons Recommended Citation Parry, Donald W. and Ricks, Stephen D., "The eD ad Sea Scrolls: Questions and Responses for Latter-day Saints" (2000). Maxwell Institute Publications. 25. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/mi/25 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maxwell Institute Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Preface What is the Copper Scroll? Do the Dead Sea Scrolls contain lost books of the Bible? Did John the Baptist study with the people of Qumran? What is the Temple Scroll? What about DNA research and the scrolls? We have responded to scores of such questions on many occasions—while teaching graduate seminars and Hebrew courses at Brigham Young University, presenting papers at professional symposia, and speaking to various lay audiences. These settings are always positive experiences for us, particularly because they reveal that the general membership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has a deep interest in the scrolls and other writings from the ancient world. The nonbiblical Dead Sea Scrolls are of great import because they shed much light on the cultural, religious, and political position of some of the Jews who lived shortly before and during the time of Jesus Christ. -

The Genius and Limitations of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik Z"L

The Genius and Limitations of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik z"l Byline: Rabbi Dr. Nathan Lopes Cardozo is Dean of the David Cardozo Academy in Jerusalem. Thoughts to Ponder 529 The Genius and Limitations of Rabbi Joseph Ber Soloveitchik z”l * Nathan Lopes Cardozo Based on an introduction to a discussion between Professor William Kolbrener and Professor Elliott Malamet (1) Honoring the publication of Professor William Kolbrener’s new book “The Last Rabbi” (2) Yad Harav Nissim, Jerusalem, on Feb. 1, 2017 Dear Friends, I never had the privilege of meeting Rav Soloveitchik z”l or learning under him. But I believe I have read all of his books on Jewish philosophy and Halacha, and even some of his Talmudic novellae and halachic decisions. I have also spoken with many of his students. Here are my impressions. No doubt Rav Soloveitchik was a Gadol Ha-dor (a great sage of his generation). He was a supreme Talmudist and certainly one of the greatest religious thinkers of our time. His literary output is incredible. Still, I believe that he was not a mechadesh – a man whose novel ideas really moved the Jewish tradition forward, especially regarding Halacha. He did not solve major halachic problems. This may sound strange, because almost no one has written as many novel ideas about Halacha as Rav Soloveitchik (3). His masterpiece, Halakhic Man, is perhaps the prime example. Before Rav Soloveitchik appeared on the scene, nobody – surely not in mainstream Orthodoxy – had seriously dealt with the ideology and philosophy of Halacha (4). Page 1 In fact, the reverse is true. -

Saul Lieberman and the Orthodox Part 2 Sources (PDF)

Politics of Exclusion in Judaism Saul Lieberman and the Orthodox Part 2 Tensions Lieberman, on the other hand, was…in all respects an Orthodox Jew. Yet despite the fact that Lieberman's focus was almost exclusively on scholarship and not on religious developments in the Conservative movement, this did not lessen the anger in the Orthodox world at what was regarded as a betrayal on Lieberman's part and a blow to Orthodox attempts to portray the Seminary as a false version of Judaism. Aaron Pechenik recalled that Jacob Levinson, a prominent New York rabbi active in the Mizrachi movement, asked him to organize a meeting of leaders of Mizrachi and Agudat ha- Rabbanim to discuss Lieberman's teaching at the Seminary. According to Pechenik, R. Meir Bar-Ilan, Lieberman's father-in-law who was in New York at the time, explained that he was opposed to what Lieberman was doing, but that his son-in-law felt that he had no choice. In Palestine he simply did not have the economic security that would enable him to devote himself to scholarship. It is indeed true that at the Seminary Lieberman was freed of his financial concerns and his workload was very light, meaning that he was able to focus on scholarly pursuits. In fact, this was the reason Lieberman himself gave Pechenik for remaining there. In addition, in one of Lieberman's letters to Ginzberg from before he came to the Seminary, what stands out is Lieberman's desire to work in an environment conducive to scholarship. Yet it is possible that these were not the only reasons Lieberman chose to join the faculty and continue at the Seminary. -

The Anti-Samaritan Attitude As Reflected in Rabbinic Midrashim

religions Article The Anti‑Samaritan Attitude as Reflected in Rabbinic Midrashim Andreas Lehnardt Faculty of Protestant Theology, Johannes Gutenberg‑University Mainz, 55122 Mainz, Germany; lehnardt@uni‑mainz.de Abstract: Samaritans, as a group within the ranges of ancient ‘Judaisms’, are often mentioned in Talmud and Midrash. As comparable social–religious entities, they are regarded ambivalently by the rabbis. First, they were viewed as Jews, but from the end of the Tannaitic times, and especially after the Bar Kokhba revolt, they were perceived as non‑Jews, not reliable about different fields of Halakhic concern. Rabbinic writings reflect on this change in attitude and describe a long ongoing conflict and a growing anti‑Samaritan attitude. This article analyzes several dialogues betweenrab‑ bis and Samaritans transmitted in the Midrash on the book of Genesis, Bereshit Rabbah. In four larger sections, the famous Rabbi Me’ir is depicted as the counterpart of certain Samaritans. The analyses of these discussions try to show how rabbinic texts avoid any direct exegetical dispute over particular verses of the Torah, but point to other hermeneutical levels of discourse and the rejection of Samari‑ tan claims. These texts thus reflect a remarkable understanding of some Samaritan convictions, and they demonstrate how rabbis denounced Samaritanism and refuted their counterparts. The Rabbi Me’ir dialogues thus are an impressive literary witness to the final stages of the parting of ways of these diverging religious streams. Keywords: Samaritans; ancient Judaism; rabbinic literature; Talmud; Midrash Citation: Lehnardt, Andreas. 2021. The Anti‑Samaritan Attitude as 1 Reflected in Rabbinic Midrashim. The attitudes towards the Samaritans (or Kutim ) documented in rabbinical literature 2 Religions 12: 584. -

Politics of Exclusion in Judaism

Politics of Exclusion in Judaism Saul Lieberman and the Orthodox Part 3 In 1959 Lieberman became rector of the Seminary, and one of his responsibilities was "guiding the general religious policy of the institution." Thus, there is certainly justice in the assertion that, whatever his personal religious commitments, Lieberman had become part and parcel of the Conservative movement and was assisting it at the time that the Orthodox were attempting to expose what they regarded as the Conservative's distortions of halakha. Furthermore, there is no question that the leaders of Conservativism were able to use the presence of Lieberman at the Seminary to help legitimize the institution when it was challenged on religious grounds. For example, when Chief Rabbi Herzog came to New York he was willing to meet with some members of the Seminary faculty, but would not enter the building because Kaplan worked there. Finkelstein recalled telling Herzog, "It can't be as bad as you think if [Saul] Lieberman sits on the faculty." The presence of Kaplan at the Seminary was one of many problems mentioned in the following nasty letter Lieberman received: Dear Sir, For the sake of Parnasah and glory you have sold yourself to the Sitra Achra [the other side]. Do you not know that you are lending prestige to Mordecai Kaplan (Yimach Shemo) and to the other Kofrim at the Seminary, as well as to the graduates who are almost in every case M'gulche-Taar and Boale-Niddah? The United States has many Rabbinical Schools where honest young men are studying Torah and developing Talmide-Chachamim. -

![Qumran Hebrew (With a Trial Cut [1Qs])*](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9626/qumran-hebrew-with-a-trial-cut-1qs-1289626.webp)

Qumran Hebrew (With a Trial Cut [1Qs])*

QUMRAN HEBREW (WITH A TRIAL CUT [1QS])* Gary A. Rendsburg Rutgers University One would think that after sixty years of studying the scrolls, scholars would have reached a consensus concerning the nature of the language of these texts. But such is not the case—the picture is no different for Qumran Hebrew (QH) than it is for identifying the sect of the Qum- ran community, for understanding the origins of the scroll depository in the caves, or for the classification of the archaeological remains at Qumran. At first glance, this is a bit difficult to comprehend, since in theory, at least, linguistic research should be the most objective form of scholarly inquiry, and the facts should speak for themselves—in contrast to, let’s say, the interpretation of texts, where subjectivity may be considered necessary at all times. But as we shall see, even though the data themselves are derived from purely empirical observation, the interpretation of the linguistic picture that emerges from the study of Qumran Hebrew has no less a range of options than the other subjects canvassed during this symposium. Before entering into such discussion, however, let us begin with the presentation of some basic facts. Of the 930 assorted documents from Qumran, 790, or about 85% of them are written in Hebrew (120 or about 13% are written in Aramaic, and 20 or about 2% are written in Greek). Of these 930, about 230 are biblical manuscripts, which * It was my pleasure to present this paper on three occasions during calendar year 2008: first and most importantly at the symposium entitled “The Dead Sea Scrolls at 60: The Scholarly Contributions of NYU Faculty and Alumni” (March 6), next at the “Semitic Philology Workshop” of Harvard University (November 20), and finally at the panel on “New Directions in Dead Sea Scrolls Scholarship” at the annual meeting of the Association of Jewish Studies held in Washington, D.C. -

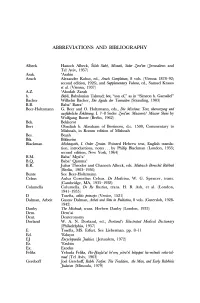

Abbreviations and Bibliography

ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY Albeck Hanoch Albeck, Sifah Sidre, Misnah, Seder Zera'im (Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, 1957) Arak. 'Arakin Aruch Alexander Kohut, ed., Aruch Completum, 8 vols. (Vienna 1878-92; second edition, 1926), and Supplementary Volume, ed., Samuel Krauss et al. (Vienna, 193 7) A.Z. 'Abodah Zarah b. Babli, Babylonian Talmud; ben, "son of," as in "Simeon b. Gamaliel" Bacher Wilhelm Bacher, Die Agada der Tannaiten (Strassling, 1903) B.B. Baba' Batra' Beer-Holtzmann G. Beer and 0. Holtzmann, eds., Die Mischna: Text, iiberset::;ung und ausfiihrliche Erkliirung, I. 7-8 Seder Zera'im: Maaserotl Mauser Sheni by Wolfgang Bunte (Berlin, 1962) Bek. Bekhorot Bert Obadiah b. Abraham of Bertinoro, d.c. 1500, Commentary to Mishnah, in Romm edition of Mishnah Bes. Be~ah Bik. Bikkurim Blackman Mishnayoth, I. Order Zeraim. Pointed Hebrew text, English transla tion, introductions, notes ... by Philip Blackman (London, 1955; second edition, New York, 1964) B.M. Baba' Mesi'a' B.Q Baba' Qamma' B.R. Julius Theodor and Chanoch Albeck, eds. Midrasch Bereschit Rabbah (Berlin, 1903-1936) Bunte See Beer-Holtzmann Celsus Aulus Cornelius Celsus. De Medicina, W. G. Spencer, trans. (Cambridge, MA, 1935-1938) Columella Columella. De Re Rustica, trans. H. B. Ash, et al. (London, 1941-1955) D Tosefta, editio princeps (Venice, 1521) Dalman, Arbeit Gustav Dalman, Arbeit und Sitte in Paliistina, 8 vols. (Gutersloh, 1928- 1942) Danby The Mishnah, trans. Herbert Danby (London, 1933) Dem. Dem'ai Deut. Deuteronomy Dorland W. A. N. Dorland, ed., Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (Philadelphia, 195 7) E Tosefta, MS. Erfurt. See Lieberman. pp. 8-11 Ed. -

The Eschatology of the Dead Sea Scrolls

Eruditio Ardescens The Journal of Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary Volume 2 Issue 2 Article 1 February 2016 The Eschatology of the Dead Sea Scrolls J. Randall Price Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/jlbts Part of the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Price, J. Randall (2016) "The Eschatology of the Dead Sea Scrolls," Eruditio Ardescens: Vol. 2 : Iss. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/jlbts/vol2/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in Eruditio Ardescens by an authorized editor of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Eschatology of the Dead Sea Scrolls J. Randall Price, Ph.D. Center for Judaic Studies Liberty University [email protected] Recent unrest in the Middle East regularly stimulates discussion on the eschatological interpretation of events within the biblical context. In light of this interest it is relevant to consider the oldest eschatological interpretation of biblical texts that had their origin in the Middle East – the Dead Sea Scrolls. This collection of some 1,000 and more documents that were recovered from caves along the northwestern shores of the Dead Sea in Israel, has become for scholars of both the Old and New Testaments a window into Jewish interpretation in the Late Second Temple period, a time known for intense messianic expectation. The sectarian documents (non-biblical texts authored by the Qumran Sect or collected by the Jewish Community) among these documents are eschatological in nature and afford the earliest and most complete perspective into the thinking of at least one Jewish group at the time of Jesus’ birth and the formation of the early church. -

Sex and Ritual in the Dead Sea Scrolls by Ita Sheres and Anne Kohn Blau

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, Classics and Religious Studies Department Classics and Religious Studies December 1996 Review of The Truth About the Virgin: Sex and Ritual in the Dead Sea Scrolls by Ita Sheres and Anne Kohn Blau Sidnie White Crawford University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/classicsfacpub Part of the Classics Commons Crawford, Sidnie White, "Review of The Truth About the Virgin: Sex and Ritual in the Dead Sea Scrolls by Ita Sheres and Anne Kohn Blau" (1996). Faculty Publications, Classics and Religious Studies Department. 60. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/classicsfacpub/60 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Classics and Religious Studies at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, Classics and Religious Studies Department by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in Bible Review XII (December 1996), pp. 12–14. Copyright © 1996 Society for Biblical Archeology. Used by permission. The Truth About the Virgin: It is in the later chapters that Sheres Sex and Ritual in the Dead Sea and Blau embark on their dangerous journey into the realm of speculation. Scrolls Their main thesis, contained in chapters 4 through 7, is that the male covenanters Ita Sheres and Anne Kohn Blau at Qumran practiced an elaborate ritual (New York: Continuum, 1995) 236 pp., $27.50 of castration, which left them incapable REVIEWED BY of participating in sexual acts, any and SIDNIE WHITE CRAWFORD all of which the sect considered pollut- ing. -

Texts, Scribes, Caves, and Scholars

University of Birmingham Texts, Scribes and Scholars: Reflections on a Busy Decade in Dead Sea Scrolls Research Hempel, Charlotte DOI: 10.1177/0014524608101841 Citation for published version (Harvard): Hempel, C 2009, 'Texts, Scribes and Scholars: Reflections on a Busy Decade in Dead Sea Scrolls Research', The Expository Times, vol. 120, no. 6, pp. 272-276. https://doi.org/10.1177/0014524608101841 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. Take down policy While the University of Birmingham exercises care and attention in making items available there are rare occasions when an item has been uploaded in error or has been deemed to be commercially or otherwise sensitive.