Marc Hirshman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of Bibliographic References to Talmudic Literature

H-Judaic Internet Resource: Index of Bibliographic References to Talmudic Literature Discussion published by Moshe Feifer on Thursday, March 19, 2015 THE SAUL LIEBERMAN INSTITUTE OF TALMUDIC RESEARCH THE JEWISH THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY The Index of Bibliographic References to Talmudic Literature We are pleased to announce that the Lieberman Institute'sIndex of References Dealing with Talmudic Literature is available at http://lieberman-index.org. Introduction What is the Index? The Index is a comprehensive online research tool directing the user to discussions and interpretations of Talmudic passages found in both modern academic research and medieval Talmudic scholarship (Geonim and Rishonim). By clicking any Talmudic passage, the user will receive a list of specific books and page numbers within them discussing the selected passage. The Index is revolutionizing Talmudic research by supplying scholars with quick and easy access to pertinent information. Preceding the establishment of the index project, the task of finding specific bibliographical references that today takes minutes would take many hours or even days of work. The Index radically alters old methods of bibliographical searching and brings Talmudic research up to par with contemporary standards. In addition to those involved in Talmudic studies per se, the index is a vital aid to those engaged in all Judaic, ancient near east, or comparative religion studies to the extent that they relate at times to Talmudic texts. Thus, the database already makes an extremely significant contribution to all associated fields of research and study by enabling scholars, students or lay audience to quickly and comprehensively access relevant scholarship. Description Citation: Moshe Feifer. -

Jewish Intertestamental and Early Rabbinic Literature: an Annotated Bibliographic Resource Updated Again (Part 2)

JETS 63.4 (2020): 789–843 JEWISH INTERTESTAMENTAL AND EARLY RABBINIC LITERATURE: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHIC RESOURCE UPDATED AGAIN (PART 2) DAVID W. CHAPMAN AND ANDREAS J. KÖSTENBERGER* Part 1 of this annotated bibliography appeared in the previous issue of JETS (see that issue for an introduction to this resource). This again is the overall struc- ture: Part 1: 1. General Reference Tools; 2. Old Testament Versions; 3. Apocrypha; 4. Pseudepigrapha; Part 2: 5. Dead Sea Scrolls; 6. Individual Authors (Philo, Jose- phus, Pseudo-Philo, Fragmentary Works); 7. Rabbinic Literature; 8. Other Early Works from the Rabbinic Period; 9. Addenda to Part 1. 5. DEAD SEA SCROLLS While the Dead Sea Scrolls are generally associated with Qumran, properly they also cover discoveries from approximately a dozen other sites in the desert wilderness surrounding the Dead Sea, such as those at Naal ever, Murabbaat, and Masada. The approximately 930 MSS from Qumran were penned from the 3rd c. BC through the 1st c. AD. The Masada texts include Jewish scrolls from the time leading up to the Roman conquest (AD 73) and subsequent Roman documents. The finds at Naal ever and Murabbaat include documents from the time of the Bar Kokhba revolt (AD 132–135). Other Bar Kokhba era documents are known from Ketef Jericho, Wadi Sdeir, Naal Mishmar, and Naal eelim (see DJD 38). For a full accounting, see the lists by Tov under “Bibliography” below. The non- literary documentary papyri (e.g. wills, deeds of sale, marriage documents, etc.) are not covered below. Recent archaeological efforts seeking further scrolls from sur- rounding caves (esp. -

By Tamar Kadari* Abstract Julius Theodor (1849–1923)

By Tamar Kadari* Abstract This article is a biography of the prominent scholar of Aggadic literature, Rabbi Dr Julius Theodor (1849–1923). It describes Theodor’s childhood and family and his formative years spent studying at the Breslau Rabbinical Seminary. It explores the thirty one years he served as a rabbi in the town of Bojanowo, and his final years in Berlin. The article highlights The- odor’s research and includes a list of his publications. Specifically, it focuses on his monumental, pioneering work preparing a critical edition of Bereshit Rabbah (completed by Chanoch Albeck), a project which has left a deep imprint on Aggadic research to this day. Der folgende Artikel beinhaltet eine Biographie des bedeutenden Erforschers der aggadischen Literatur Rabbiner Dr. Julius Theodor (1849–1923). Er beschreibt Theodors Kindheit und Familie und die ihn prägenden Jahre des Studiums am Breslauer Rabbinerseminar. Er schil- dert die einunddreissig Jahre, die er als Rabbiner in der Stadt Bojanowo wirkte, und seine letzten Jahre in Berlin. Besonders eingegangen wird auf Theodors Forschungsleistung, die nicht zuletzt an der angefügten Liste seiner Veröffentlichungen ablesbar ist. Im Mittelpunkt steht dabei seine präzedenzlose monumentale kritische Edition des Midrasch Bereshit Rabbah (die Chanoch Albeck weitergeführt und abgeschlossen hat), ein Werk, das in der Erforschung aggadischer Literatur bis heute nachwirkende Spuren hinterlassen hat. Julius Theodor (1849–1923) is one of the leading experts of the Aggadic literature. His major work, a scholarly edition of the Midrash Bereshit Rabbah (BerR), completed by Chanoch Albeck (1890–1972), is a milestone and foundation of Jewish studies research. His important articles deal with key topics still relevant to Midrashic research even today. -

The Genius and Limitations of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik Z"L

The Genius and Limitations of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik z"l Byline: Rabbi Dr. Nathan Lopes Cardozo is Dean of the David Cardozo Academy in Jerusalem. Thoughts to Ponder 529 The Genius and Limitations of Rabbi Joseph Ber Soloveitchik z”l * Nathan Lopes Cardozo Based on an introduction to a discussion between Professor William Kolbrener and Professor Elliott Malamet (1) Honoring the publication of Professor William Kolbrener’s new book “The Last Rabbi” (2) Yad Harav Nissim, Jerusalem, on Feb. 1, 2017 Dear Friends, I never had the privilege of meeting Rav Soloveitchik z”l or learning under him. But I believe I have read all of his books on Jewish philosophy and Halacha, and even some of his Talmudic novellae and halachic decisions. I have also spoken with many of his students. Here are my impressions. No doubt Rav Soloveitchik was a Gadol Ha-dor (a great sage of his generation). He was a supreme Talmudist and certainly one of the greatest religious thinkers of our time. His literary output is incredible. Still, I believe that he was not a mechadesh – a man whose novel ideas really moved the Jewish tradition forward, especially regarding Halacha. He did not solve major halachic problems. This may sound strange, because almost no one has written as many novel ideas about Halacha as Rav Soloveitchik (3). His masterpiece, Halakhic Man, is perhaps the prime example. Before Rav Soloveitchik appeared on the scene, nobody – surely not in mainstream Orthodoxy – had seriously dealt with the ideology and philosophy of Halacha (4). Page 1 In fact, the reverse is true. -

Saul Lieberman and the Orthodox Part 2 Sources (PDF)

Politics of Exclusion in Judaism Saul Lieberman and the Orthodox Part 2 Tensions Lieberman, on the other hand, was…in all respects an Orthodox Jew. Yet despite the fact that Lieberman's focus was almost exclusively on scholarship and not on religious developments in the Conservative movement, this did not lessen the anger in the Orthodox world at what was regarded as a betrayal on Lieberman's part and a blow to Orthodox attempts to portray the Seminary as a false version of Judaism. Aaron Pechenik recalled that Jacob Levinson, a prominent New York rabbi active in the Mizrachi movement, asked him to organize a meeting of leaders of Mizrachi and Agudat ha- Rabbanim to discuss Lieberman's teaching at the Seminary. According to Pechenik, R. Meir Bar-Ilan, Lieberman's father-in-law who was in New York at the time, explained that he was opposed to what Lieberman was doing, but that his son-in-law felt that he had no choice. In Palestine he simply did not have the economic security that would enable him to devote himself to scholarship. It is indeed true that at the Seminary Lieberman was freed of his financial concerns and his workload was very light, meaning that he was able to focus on scholarly pursuits. In fact, this was the reason Lieberman himself gave Pechenik for remaining there. In addition, in one of Lieberman's letters to Ginzberg from before he came to the Seminary, what stands out is Lieberman's desire to work in an environment conducive to scholarship. Yet it is possible that these were not the only reasons Lieberman chose to join the faculty and continue at the Seminary. -

What Is an Emendation? Jewish Tradition Holds That the Soferim

What is an Emendation? Jewish tradition holds that the Soferim (Levite scribes) were responsible for copying and maintaining the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible or Christian Old Testament) after the Jews returned from Babylonian Exile. While the Bible speaks of several scribes before the Exile, Jewish tradition recognizes Ezra as the first who was given the task of maintaining the Tanakh’s accuracy and providing the correct interpretation of its meaning. “This Ezra went up from Babylon, and was a scribe skilled in the law of Moses, which the LORD God of Israel had given; and the king granted him all he requested because the hand of the LORD his God was upon him.” (Ezra 7:6) “Now this is the copy of the decree which King Artaxerxes gave to Ezra the priest, the scribe, learned in the words of the commandments of the LORD and His statutes to Israel:” (Ezra 7:11) At the end of the second century (200 A.D.), early rabbinic sources came to the conclusion that several passages of the present text differed from the ancient manuscripts. In the third century, Rabbi Simon ben Pazzi called these presumed differences “tikkun Soferim”, which means “emendations of the Scribes” (Midrash Genesis Rabbah xlix. 7). The Midrash, an exegetical and homiletic method of interpreting the Old Testament also accepted the view of scribal emendation. Initially preserved in oral form, they were written down in the second century A.D. They exist today as exegetical or homiletical commentaries on the Tanakh. Later, the majority of Masoretes accepted this view, and the assumed changes were attributed to either: Ezra or, Ezra and Nehemiah or, Ezra and the Soferim or Ezra, Nehemiah, Zechariah, Haggai and Baruch. -

אוסף מרמורשטיין the Marmorstein Collection

אוסף מרמורשטיין The Marmorstein Collection Brad Sabin Hill THE JOHN RYLANDS LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER Manchester 2017 1 The Marmorstein Collection CONTENTS Acknowledgements Note on Bibliographic Citations I. Preface: Hebraica and Judaica in the Rylands -Hebrew and Samaritan Manuscripts: Crawford, Gaster -Printed Books: Spencer Incunabula; Abramsky Haskalah Collection; Teltscher Collection; Miscellaneous Collections; Marmorstein Collection II. Dr Arthur Marmorstein and His Library -Life and Writings of a Scholar and Bibliographer -A Rabbinic Literary Family: Antecedents and Relations -Marmorstein’s Library III. Hebraica -Literary Periods and Subjects -History of Hebrew Printing -Hebrew Printed Books in the Marmorstein Collection --16th century --17th century --18th century --19th century --20th century -Art of the Hebrew Book -Jewish Languages (Aramaic, Judeo-Arabic, Yiddish, Others) IV. Non-Hebraica -Greek and Latin -German -Anglo-Judaica -Hungarian -French and Italian -Other Languages 2 V. Genres and Subjects Hebraica and Judaica -Bible, Commentaries, Homiletics -Mishnah, Talmud, Midrash, Rabbinic Literature -Responsa -Law Codes and Custumals -Philosophy and Ethics -Kabbalah and Mysticism -Liturgy and Liturgical Poetry -Sephardic, Oriental, Non-Ashkenazic Literature -Sects, Branches, Movements -Sex, Marital Laws, Women -History and Geography -Belles-Lettres -Sciences, Mathematics, Medicine -Philology and Lexicography -Christian Hebraism -Jewish-Christian and Jewish-Muslim Relations -Jewish and non-Jewish Intercultural Influences -

A Whiteheadian Interpretation of the Zoharic Creation Story

A WHITEHEADIAN INTERPRETATION OF THE ZOHARIC CREATION STORY by Michael Gold A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida May 2016 Copyright 2016 by Michael Gold ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author wishes to express sincere gratitude to his committee members, Professors Marina Banchetti, Frederick E. Greenspahn, Kristen Lindbeck, and Eitan Fishbane for their encouragement and support throughout this project. iv ABSTRACT Author: Michael Gold Title: A Whiteheadian Interpretation of the Zoharic Creation Story Institution: Florida Atlantic University Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Marina P. Banchetti Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Year: 2016 This dissertation presents a Whiteheadian interpretation of the notions of mind, immanence and process as they are addressed in the Zohar. According to many scholars, this kabbalistic creation story as portrayed in the Zohar is a reaction to the earlier rabbinic concept of God qua creator, which emphasized divine transcendence over divine immanence. The medieval Jewish philosophers, particularly Maimonides influenced by Aristotle, placed particular emphasis on divine transcendence, seeing a radical separation between Creator and creation. With this in mind, these scholars claim that one of the goals of the Zohar’s creation story was to emphasize God’s immanence within creation. Similar to the Zohar, the process metaphysics of Alfred North Whitehead and his followers was reacting to the substance metaphysics that had dominated Western philosophy as far back as ancient Greek thought. Whitehead adopts a very similar narrative to that of the Zohar. -

The Israel Koschitzky Virtual Beit Midrash

The Israel Koschitzky Virtual Beit Midrash Special Holiday Shiur Yeshivat Har Etzion CHANUKA AND PURIM: A STUDY OF THEIR DIFFERENCES by Rabbi Nathaniel Helfgot I - Introduction From a purely halakhic point of view, we generally regard Chanuka and Purim as equal in status. Both festivals are de-rabanan (rabbinically mandated), and the issue of "pirsum ha-nes" (publicizing the miracle) is central to both of them. This trend of thought finds expression in the Rambam's Mishneh Torah. As opposed to the other festivals, the halakhot of which are all dealt with individually - e.g. Hilkhot Shevitat He-asor (Yom Kippur), Hilkhot Chametz U-matza (Pesach) etc., the Rambam gives a joint heading to the laws of Chanuka and Purim: Hilkhot Megilla Ve- Chanuka. The first two chapters deal with the laws of Purim, and the third and fourth chapters deal with the laws of Chanuka. In addition, the Rambam further emphasizes the connection between these two festivals in his laws of Chanuka. In 3:3 he writes: And these days are called Chanuka, and eulogies and fasting are forbidden on them as on the days of Purim. And it is a mitzva to light candles on these days based on divrei soferim, as is the reading of the Megilla. And further on, in halakha 4, the Rambam draws the following parallel: All those obligated to hear the reading of the Megilla are also obligated to light candles on Chanuka. II - Differences Based on "Divrei Kabbala" Clearly, though, these quotations do not reflect the whole picture. The most obvious difference between Chanuka and Purim is that in contrast to Chanuka, on Purim we have a text - Megillat Ester, which is part of the kitvei kodesh. -

Politics of Exclusion in Judaism

Politics of Exclusion in Judaism Saul Lieberman and the Orthodox Part 3 In 1959 Lieberman became rector of the Seminary, and one of his responsibilities was "guiding the general religious policy of the institution." Thus, there is certainly justice in the assertion that, whatever his personal religious commitments, Lieberman had become part and parcel of the Conservative movement and was assisting it at the time that the Orthodox were attempting to expose what they regarded as the Conservative's distortions of halakha. Furthermore, there is no question that the leaders of Conservativism were able to use the presence of Lieberman at the Seminary to help legitimize the institution when it was challenged on religious grounds. For example, when Chief Rabbi Herzog came to New York he was willing to meet with some members of the Seminary faculty, but would not enter the building because Kaplan worked there. Finkelstein recalled telling Herzog, "It can't be as bad as you think if [Saul] Lieberman sits on the faculty." The presence of Kaplan at the Seminary was one of many problems mentioned in the following nasty letter Lieberman received: Dear Sir, For the sake of Parnasah and glory you have sold yourself to the Sitra Achra [the other side]. Do you not know that you are lending prestige to Mordecai Kaplan (Yimach Shemo) and to the other Kofrim at the Seminary, as well as to the graduates who are almost in every case M'gulche-Taar and Boale-Niddah? The United States has many Rabbinical Schools where honest young men are studying Torah and developing Talmide-Chachamim. -

Abbreviations and Bibliography

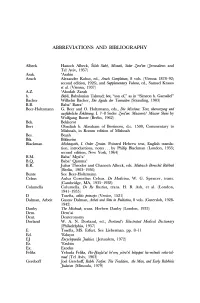

ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY Albeck Hanoch Albeck, Sifah Sidre, Misnah, Seder Zera'im (Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, 1957) Arak. 'Arakin Aruch Alexander Kohut, ed., Aruch Completum, 8 vols. (Vienna 1878-92; second edition, 1926), and Supplementary Volume, ed., Samuel Krauss et al. (Vienna, 193 7) A.Z. 'Abodah Zarah b. Babli, Babylonian Talmud; ben, "son of," as in "Simeon b. Gamaliel" Bacher Wilhelm Bacher, Die Agada der Tannaiten (Strassling, 1903) B.B. Baba' Batra' Beer-Holtzmann G. Beer and 0. Holtzmann, eds., Die Mischna: Text, iiberset::;ung und ausfiihrliche Erkliirung, I. 7-8 Seder Zera'im: Maaserotl Mauser Sheni by Wolfgang Bunte (Berlin, 1962) Bek. Bekhorot Bert Obadiah b. Abraham of Bertinoro, d.c. 1500, Commentary to Mishnah, in Romm edition of Mishnah Bes. Be~ah Bik. Bikkurim Blackman Mishnayoth, I. Order Zeraim. Pointed Hebrew text, English transla tion, introductions, notes ... by Philip Blackman (London, 1955; second edition, New York, 1964) B.M. Baba' Mesi'a' B.Q Baba' Qamma' B.R. Julius Theodor and Chanoch Albeck, eds. Midrasch Bereschit Rabbah (Berlin, 1903-1936) Bunte See Beer-Holtzmann Celsus Aulus Cornelius Celsus. De Medicina, W. G. Spencer, trans. (Cambridge, MA, 1935-1938) Columella Columella. De Re Rustica, trans. H. B. Ash, et al. (London, 1941-1955) D Tosefta, editio princeps (Venice, 1521) Dalman, Arbeit Gustav Dalman, Arbeit und Sitte in Paliistina, 8 vols. (Gutersloh, 1928- 1942) Danby The Mishnah, trans. Herbert Danby (London, 1933) Dem. Dem'ai Deut. Deuteronomy Dorland W. A. N. Dorland, ed., Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (Philadelphia, 195 7) E Tosefta, MS. Erfurt. See Lieberman. pp. 8-11 Ed. -

Qumran Yaḥad and Rabbinic Ḥăbûrâ

Dead Sea Discoveries 16 (2009) 433–453 brill.nl/dsd Qumran Yaḥad and Rabbinic Ḥăbûrâ: A Comparison Reconsidered1 Steven D. Fraade Department of Religious Studies, Yale University, P.O. Box 208287 451 College Street, New Haven, CT 06520-8287 [email protected] Abstract Since soon after the initial discoveries and publications of the Dead Sea Scrolls, scholars have compared the yahaḍ of the scrolls with the hạ bûrâ̆ of early rabbinic literature and sought to establish a historical relationship and developmental pro- gression between the two types of communal organization. Th e present article reviews select but representative examples from such scholarship, seeking to reveal their underlying presumptions and broader implications, while questioning whether the available evidence allows for the sorts of sociological comparisons and historical reconstructions that they adduce. Keywords Essenes, hạ bûrâ̆ , historiography, history of scholarship, Pharisees, rabbinic literature, yahaḍ 1. Introduction In the fi rst scholarly announcement of the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, William F. Albright, having seen only four scrolls, presciently wrote early in 1948: 1 Th is article began as a paper at the Society of Biblical Literature, 2007 Annual Meeting, San Diego, CA, November 18, 2007. I wish to acknowledge the gener- ous and sage assistance of the following colleagues in preparing this article for publication: John Collins, Yair Furstenberg, Yonder Gillihan, and Charlotte Hempel. © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2009 DOI: 10.1163/156851709X474012 434 S. D. Fraade / Dead Sea Discoveries 16 (2009) 433–453 It is easy to surmise that the new discovery will revolutionize intertes- tamental studies, and that it will soon antiquate all present handbooks on the background of the New Testament and on the textual criticism and interpretation of the Old Testament.2 Th e absence of any mention of early rabbinic literature as a fi eld that might be aff ected by the new-found scrolls was not a mere oversight.