Talmud: East and West

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of Bibliographic References to Talmudic Literature

H-Judaic Internet Resource: Index of Bibliographic References to Talmudic Literature Discussion published by Moshe Feifer on Thursday, March 19, 2015 THE SAUL LIEBERMAN INSTITUTE OF TALMUDIC RESEARCH THE JEWISH THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY The Index of Bibliographic References to Talmudic Literature We are pleased to announce that the Lieberman Institute'sIndex of References Dealing with Talmudic Literature is available at http://lieberman-index.org. Introduction What is the Index? The Index is a comprehensive online research tool directing the user to discussions and interpretations of Talmudic passages found in both modern academic research and medieval Talmudic scholarship (Geonim and Rishonim). By clicking any Talmudic passage, the user will receive a list of specific books and page numbers within them discussing the selected passage. The Index is revolutionizing Talmudic research by supplying scholars with quick and easy access to pertinent information. Preceding the establishment of the index project, the task of finding specific bibliographical references that today takes minutes would take many hours or even days of work. The Index radically alters old methods of bibliographical searching and brings Talmudic research up to par with contemporary standards. In addition to those involved in Talmudic studies per se, the index is a vital aid to those engaged in all Judaic, ancient near east, or comparative religion studies to the extent that they relate at times to Talmudic texts. Thus, the database already makes an extremely significant contribution to all associated fields of research and study by enabling scholars, students or lay audience to quickly and comprehensively access relevant scholarship. Description Citation: Moshe Feifer. -

Marc Hirshman

THE TIKVAH CENTER FOR LAW & JEWISH CIVILIZATION Professor Moshe Halbertal Professor J.H.H. Weiler Directors of The Tikvah Center Tikvah Working Paper 07/12 Marc Hirshman Individual and Group Learning in Rabbinic Literature: Some Key Terms NYU School of Law • New York, NY 10011 The Tikvah Center Working Paper Series can be found at http://www.nyutikvah.org/publications.html All rights reserved. No part of this paper may be reproduced in any form without permission of the author. ISSN 2160‐8229 (print) ISSN 2160‐8253 (online) Copy Editor: Danielle Leeds Kim © Marc Hirshman 2012 New York University School of Law New York, NY 10011 USA Publications in the Series should be cited as: AUTHOR, TITLE, TIKVAH CENTER WORKING PAPER NO./YEAR [URL] Individual and Group Learning in Rabbinic Literature INDIVIDUAL AND GROUP LEARNING IN RABBINIC LITERATURE: SOME KEY TERMS By Marc Hirshman A. Foundations of Education in Biblical and Second Temple Times Wilhelm Bacher, the great late 19th, early 20th scholar, published in 1903 a wonderful essay entitled " Das altjüdische Schulewesen", in which he declared Nehemiah 8, 1-8, which describes the public reading of scripture, " der Geburtstag des altjüdischen Schulweis". From that day on 1 Tishre 445 b.c.e, Bacher would have it, the public recitation of Torah and its teaching would become central to second Temple Judaism, and its rabbinic heirs in the first five centuries of the common era. Indeed, Ezra's commission from Artaxerxes includes appointments of "judges and magistrates to judge all the people… and to teach…" (Ezra 7, 25). This close connection between the judicial system and the educational system also characterizes the rabbinic period, succinctly captured in the opening quote of the tractate of Avot 1,1. -

The Genius and Limitations of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik Z"L

The Genius and Limitations of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik z"l Byline: Rabbi Dr. Nathan Lopes Cardozo is Dean of the David Cardozo Academy in Jerusalem. Thoughts to Ponder 529 The Genius and Limitations of Rabbi Joseph Ber Soloveitchik z”l * Nathan Lopes Cardozo Based on an introduction to a discussion between Professor William Kolbrener and Professor Elliott Malamet (1) Honoring the publication of Professor William Kolbrener’s new book “The Last Rabbi” (2) Yad Harav Nissim, Jerusalem, on Feb. 1, 2017 Dear Friends, I never had the privilege of meeting Rav Soloveitchik z”l or learning under him. But I believe I have read all of his books on Jewish philosophy and Halacha, and even some of his Talmudic novellae and halachic decisions. I have also spoken with many of his students. Here are my impressions. No doubt Rav Soloveitchik was a Gadol Ha-dor (a great sage of his generation). He was a supreme Talmudist and certainly one of the greatest religious thinkers of our time. His literary output is incredible. Still, I believe that he was not a mechadesh – a man whose novel ideas really moved the Jewish tradition forward, especially regarding Halacha. He did not solve major halachic problems. This may sound strange, because almost no one has written as many novel ideas about Halacha as Rav Soloveitchik (3). His masterpiece, Halakhic Man, is perhaps the prime example. Before Rav Soloveitchik appeared on the scene, nobody – surely not in mainstream Orthodoxy – had seriously dealt with the ideology and philosophy of Halacha (4). Page 1 In fact, the reverse is true. -

Barry Wimpfheimer, Ed., Wisdom of Bat Sheva: the Dr

BARRY SCOTT WIMPFHEIMER curriculum vitae Department of Religious Studies Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences Northwestern University 1860 Campus Drive, 4-140 Evanston, Illinois 60208-2164 [email protected] 847-491-2618 POSITIONS Associate Professor, Northwestern University, Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences, Department of Religious Studies (Fall 2013-Present) Critical Theory, Jewish Studies and Legal Studies Committees Associate Professor, Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law (Fall 2013-Present) Director, Crown Family Center for Jewish and Israel Studies & Jewish Studies Program, Northwestern University (Fall 2012-Summer 2016) Fellow, Alice Kaplan Institute for the Humanities, Northwestern University (Fall 2011-Spring 2012) Assistant Professor, Northwestern University, Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences, Department of Religious Studies, (Summer 2007-Spring 2013) Director of Undergraduate Studies, (Fall 2008-Spring 2009) Assistant Professor, Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law (Summer 2007-Spring 2013) College Fellow, Northwestern University, Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences, Department of Religion (Summer 2006-Spring 2007) Assistant Professor. The Pennsylvania State University, Department of History and Religious Studies; Malvin and Lea Bank Early Career Professor of Jewish Studies (Fall 2005- Spring 2006). Harry Starr Fellow. Harvard University Center for Jewish Studies (Spring 2006). Instructor. University of Pennsylvania, Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies (Spring 2005). EDUCATION Columbia University, New York, New York. Wimpfheimer cv September 19 p. 1 Ph.D., with Distinction, October 2005. Religion. Committee: Professors David Weiss Halivni, Elizabeth Castelli, Jeffrey Rubenstein, Alan Segal, Michael Stanislawski. M.Phil., October 2004. Religion. M.A., October 2003. Religion. Yeshiva University, New York, New York. 1996-2000. Rabbinic Ordination, June 2000. -

Saul Lieberman and the Orthodox Part 2 Sources (PDF)

Politics of Exclusion in Judaism Saul Lieberman and the Orthodox Part 2 Tensions Lieberman, on the other hand, was…in all respects an Orthodox Jew. Yet despite the fact that Lieberman's focus was almost exclusively on scholarship and not on religious developments in the Conservative movement, this did not lessen the anger in the Orthodox world at what was regarded as a betrayal on Lieberman's part and a blow to Orthodox attempts to portray the Seminary as a false version of Judaism. Aaron Pechenik recalled that Jacob Levinson, a prominent New York rabbi active in the Mizrachi movement, asked him to organize a meeting of leaders of Mizrachi and Agudat ha- Rabbanim to discuss Lieberman's teaching at the Seminary. According to Pechenik, R. Meir Bar-Ilan, Lieberman's father-in-law who was in New York at the time, explained that he was opposed to what Lieberman was doing, but that his son-in-law felt that he had no choice. In Palestine he simply did not have the economic security that would enable him to devote himself to scholarship. It is indeed true that at the Seminary Lieberman was freed of his financial concerns and his workload was very light, meaning that he was able to focus on scholarly pursuits. In fact, this was the reason Lieberman himself gave Pechenik for remaining there. In addition, in one of Lieberman's letters to Ginzberg from before he came to the Seminary, what stands out is Lieberman's desire to work in an environment conducive to scholarship. Yet it is possible that these were not the only reasons Lieberman chose to join the faculty and continue at the Seminary. -

Biography of Lee I. Levine

Biography of Lee I. Levine Lee Israel Levine was born on Feb. 1, 1939, in Bangor, Maine, to Rabbi Dr. Harry O. H. Levine and Irene R. Levine (née Ginsburgh). He attended the Akiba Academy in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and a public high school in Steubenville, Ohio, where his father served as a congregational rabbi. Summers were spent at Camp Ramah. Lee attended Columbia College in New York, majoring in philosophy. At the same time, he studied in the undergraduate program at the Jewish Theological Semi- nary, majoring in Talmud. He graduated from both institutions in 1961, earning a B.A. from Columbia and a B.H.L. in Talmud from JTS. In June 1961, he married Mira Karp of Buffalo, New York. Lee and Mira spent the 1959–60 academic year at Machon Greenberg (Hayyim Greenberg Institute for Teachers from the Diaspora) and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. From 1961 to 1965, Lee studied in the rabbinical program at the Jewish Theological Seminary with the distinguished rabbis and scholars Saul Lieberman, David Weiss Halivni, Moshe Zucker, and Gerson Cohen. He received his M.H.L. in Talmud in 1963 and rabbinic ordination from JTS in 1965. In 1963, Lee pursued his graduate studies in Jewish and Ancient History at Co- lumbia University with Professors Gerson Cohen and Morton Smith. After receiving his M.A. in 1966, he continued his doctoral studies under the mentorship of Cohen and Smith and was awarded his Ph.D. in 1970. While researching his dissertation on Caesarea under Roman Rule, he spent the 1968–69 academic year at the Institute of Archaeology of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. -

The Irreconcilability of Judaism and Modern Biblical Scholarship

Studies in the Bible and Antiquity Volume 8 Article 3 2016 The Irreconcilability of Judaism and Modern Biblical Scholarship James L. Kugel Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sba Part of the Biblical Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Kugel, James L. (2016) "The Irreconcilability of Judaism and Modern Biblical Scholarship," Studies in the Bible and Antiquity: Vol. 8 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sba/vol8/iss1/3 This Forum is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in the Bible and Antiquity by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The Irreconcilability of Judaism and Modern Biblical Scholarship James L. Kugel Thanks to the work of scholars of the Hebrew Bible over the last two centuries or so, we now know a great deal about how and when various biblical texts were composed and assembled; in fact, this has been the focus of much of modern biblical scholarship. One thing has become clear as a result. Our biblical texts are actually the product of multiple acts of rewriting. All our canonical books have been found to be, in some degree, the result of editorial expansion, rearrangement, and redaction introduced by various anonymous ancient scholars. This raises an important question about those ancient scholars. To put it bluntly: How dare they? If you, an ancient Israelite, believe that Scripture -

Politics of Exclusion in Judaism

Politics of Exclusion in Judaism Saul Lieberman and the Orthodox Part 3 In 1959 Lieberman became rector of the Seminary, and one of his responsibilities was "guiding the general religious policy of the institution." Thus, there is certainly justice in the assertion that, whatever his personal religious commitments, Lieberman had become part and parcel of the Conservative movement and was assisting it at the time that the Orthodox were attempting to expose what they regarded as the Conservative's distortions of halakha. Furthermore, there is no question that the leaders of Conservativism were able to use the presence of Lieberman at the Seminary to help legitimize the institution when it was challenged on religious grounds. For example, when Chief Rabbi Herzog came to New York he was willing to meet with some members of the Seminary faculty, but would not enter the building because Kaplan worked there. Finkelstein recalled telling Herzog, "It can't be as bad as you think if [Saul] Lieberman sits on the faculty." The presence of Kaplan at the Seminary was one of many problems mentioned in the following nasty letter Lieberman received: Dear Sir, For the sake of Parnasah and glory you have sold yourself to the Sitra Achra [the other side]. Do you not know that you are lending prestige to Mordecai Kaplan (Yimach Shemo) and to the other Kofrim at the Seminary, as well as to the graduates who are almost in every case M'gulche-Taar and Boale-Niddah? The United States has many Rabbinical Schools where honest young men are studying Torah and developing Talmide-Chachamim. -

Abbreviations and Bibliography

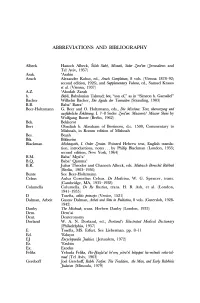

ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY Albeck Hanoch Albeck, Sifah Sidre, Misnah, Seder Zera'im (Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, 1957) Arak. 'Arakin Aruch Alexander Kohut, ed., Aruch Completum, 8 vols. (Vienna 1878-92; second edition, 1926), and Supplementary Volume, ed., Samuel Krauss et al. (Vienna, 193 7) A.Z. 'Abodah Zarah b. Babli, Babylonian Talmud; ben, "son of," as in "Simeon b. Gamaliel" Bacher Wilhelm Bacher, Die Agada der Tannaiten (Strassling, 1903) B.B. Baba' Batra' Beer-Holtzmann G. Beer and 0. Holtzmann, eds., Die Mischna: Text, iiberset::;ung und ausfiihrliche Erkliirung, I. 7-8 Seder Zera'im: Maaserotl Mauser Sheni by Wolfgang Bunte (Berlin, 1962) Bek. Bekhorot Bert Obadiah b. Abraham of Bertinoro, d.c. 1500, Commentary to Mishnah, in Romm edition of Mishnah Bes. Be~ah Bik. Bikkurim Blackman Mishnayoth, I. Order Zeraim. Pointed Hebrew text, English transla tion, introductions, notes ... by Philip Blackman (London, 1955; second edition, New York, 1964) B.M. Baba' Mesi'a' B.Q Baba' Qamma' B.R. Julius Theodor and Chanoch Albeck, eds. Midrasch Bereschit Rabbah (Berlin, 1903-1936) Bunte See Beer-Holtzmann Celsus Aulus Cornelius Celsus. De Medicina, W. G. Spencer, trans. (Cambridge, MA, 1935-1938) Columella Columella. De Re Rustica, trans. H. B. Ash, et al. (London, 1941-1955) D Tosefta, editio princeps (Venice, 1521) Dalman, Arbeit Gustav Dalman, Arbeit und Sitte in Paliistina, 8 vols. (Gutersloh, 1928- 1942) Danby The Mishnah, trans. Herbert Danby (London, 1933) Dem. Dem'ai Deut. Deuteronomy Dorland W. A. N. Dorland, ed., Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (Philadelphia, 195 7) E Tosefta, MS. Erfurt. See Lieberman. pp. 8-11 Ed. -

Qumran Yaḥad and Rabbinic Ḥăbûrâ

Dead Sea Discoveries 16 (2009) 433–453 brill.nl/dsd Qumran Yaḥad and Rabbinic Ḥăbûrâ: A Comparison Reconsidered1 Steven D. Fraade Department of Religious Studies, Yale University, P.O. Box 208287 451 College Street, New Haven, CT 06520-8287 [email protected] Abstract Since soon after the initial discoveries and publications of the Dead Sea Scrolls, scholars have compared the yahaḍ of the scrolls with the hạ bûrâ̆ of early rabbinic literature and sought to establish a historical relationship and developmental pro- gression between the two types of communal organization. Th e present article reviews select but representative examples from such scholarship, seeking to reveal their underlying presumptions and broader implications, while questioning whether the available evidence allows for the sorts of sociological comparisons and historical reconstructions that they adduce. Keywords Essenes, hạ bûrâ̆ , historiography, history of scholarship, Pharisees, rabbinic literature, yahaḍ 1. Introduction In the fi rst scholarly announcement of the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, William F. Albright, having seen only four scrolls, presciently wrote early in 1948: 1 Th is article began as a paper at the Society of Biblical Literature, 2007 Annual Meeting, San Diego, CA, November 18, 2007. I wish to acknowledge the gener- ous and sage assistance of the following colleagues in preparing this article for publication: John Collins, Yair Furstenberg, Yonder Gillihan, and Charlotte Hempel. © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2009 DOI: 10.1163/156851709X474012 434 S. D. Fraade / Dead Sea Discoveries 16 (2009) 433–453 It is easy to surmise that the new discovery will revolutionize intertes- tamental studies, and that it will soon antiquate all present handbooks on the background of the New Testament and on the textual criticism and interpretation of the Old Testament.2 Th e absence of any mention of early rabbinic literature as a fi eld that might be aff ected by the new-found scrolls was not a mere oversight. -

Ari Ackerman

ARI ACKERMAN Machon Shechter Office: (02) 679-0755 4 Avraham Granot St. ackerman at schechter.ac.il Jerusalem, 91160 Professional Positions: Academic Advisor for Mishle Program 2014- Academic Advisor for Jewish Education and Contemporay Judaism Tracks 2012-2014 Academic Advisor for Student Affairs 2010-2012, 2014- Academic Advisor for TALI Educational Leadership Program 2005-2012 Senior Lecturor in Jewish Education and Philosophy: Machon Schechter, Jerusalem, Israel Lecturor in Jewish Education and Philosophy: Machon Shechter, Jerusaelm, Israel 2001-2012 Jerusalem Fellow: The Mandel School for the Development 1999-2001 of Professional Leadership, Jerusalem, Israel Research Fellow: The Institute for Advanced Studies, School of 1996- 1999 Social Science, Princeton, New Jersey Adjunct Instructor in Jewish Philosophy: Stern College 1997- 1999 for Women, Yeshiva University Instructor in Jewish Philosophy: Drisha Institute 1997- 1999 for Jewish Education, New York Education: Ph.D.: Jewish Philosophy 1994- 2001 Hebrew University Dissertation topic: “The Philosophic Sermons of Zerahia ben Isaac Halevi Saladin: Jewish Philosophic and Sermonic Activity in Late 14th and Early 15th Century Aragon.” Master’s Degree: Jewish Philosophy 1991-1993 Hebrew University Thesis: “Zerahia Halevi’s Sermon on Genesis 22:14” Bachelor Of Arts Degree 1984-1988 Columbia University Publications: Books The Philosophic Sermons of Zerhia Halevi Saladin, Beer Sheva University Press, 2012. Edited Books Co-editor, The Jewish Political Tradition, volume two, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003. Co-editor, "Jewish Education for What?" and Other Essays of Walter Ackerman, Jerusalem: Schechter Press, 2008. Articles “The Composition of the Section on Divine Providence in Or Hashem,” Da’at 32-33 (1994) pp. 37-45. -

Download File

Halevy, Halivni and The Oral Formation of the Babylonian Talmud Ari Bergmann Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Ari Bergmann All rights reserved ABSTRACT Halevy, Halivni and The Oral Formation of the Babylonian Talmud Ari Bergmann This dissertation is dedicated to a detailed analysis and comparison of the theories on the process of the formation of the Babylonian Talmud by Yitzhak Isaac Halevy and David Weiss Halivni. These two scholars exhibited a similar mastery of the talmudic corpus and were able to combine the roles of historian and literary critic to provide a full construct of the formation of the Bavli with supporting internal evidence to support their claims. However, their historical construct and findings are diametrically opposed. Yitzhak Isaac Halevy presented a comprehensive theory of the process of the formation of the Talmud in his magnum opus Dorot Harishonim. The scope of his work was unprecedented and his construct on the formation of the Talmud encompassed the entire process of the formation of the Bavli, from the Amoraim in the 4th century to the end of the saboraic era (which he argued closed in the end of the 6th century). Halevy was the ultimate guardian of tradition and argued that the process of the formation of the Bavli took place entirely within the amoraic academy by a highly structured and coordinated process and was sealed by an international rabbinical assembly. While Halevy was primarily a historian, David Weiss Halivni is primarily a talmudist and commentator on the Talmud itself.