The Secretary and CNO on 23–24 October 1962

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Results in I and II Cycles of the Internet Music Competition 2014

Results in I and II cycles of the Internet Music Competition 2014 I cycle: Duo, chamber ensemble, piano ensemble, choir, orchestra, percussion II cycle: Piano, bassoon, flute, french horn, clarinet, oboe, saxophone, trombone, trumpet, tube Internet Music Competition which passes completely through the Internet and it is unique event since its inception. In first and second cycles of the contest in 2014, was attended by 914 contestants from 22 countries and 198 cities from 272 schools: I cycle: "Duo" – 56 contestants "Piano Ensemble" – 94 contestants "Chamber Ensemble" – 73 contestants "Choir" – 23 contestants "Orchestra" – 28 contestant "Percussion "– 13 contestants. II cycle: "Piano" – 469 contestants "Bassoon" – 7 contestants "Flute" – 82 contestants "French horn" – 3 contestants "Clarinet" – 17 contestants "Oboe" – 8 contestants "Saxophone" – 27 contestants "Trombone" – 2 contestants "Trumpet" – 9 contestants "Tube" – 3 contestants The jury was attended by 37 musicians from 13 countries, many of whom are eminent teachers, musicians and artists who teach at prestigious music institutions are soloists and play in the top 10 best orchestras and opera houses. The winners of the first cycle in Masters Final Internet Music Competition 2014: "Duo" – Djamshid Saidkarimov, Pak Artyom (Tashkent, Uzbekistan) "Piano Ensemble" – Koval Ilya, Koval Yelissey (Karaganda, Kazakhstan) "Chamber Ensemble" – Creative Quintet (Sanok, Poland) "Choir" – Womens Choir Ave musiсa HGEU (Odessa, Ukraine) "Orchestra" – “Victoria” (Samara, Russia) "Percussion" – -

Working Paper: Do Not Cite Or Circulate Without Permission

THE COPENHAGEN TEMPTATION: RETHINKING PREVENTION AND PROLIFERATION IN THE AGE OF DETERRENCE DOMINANCE Francis J. Gavin Mira Rapp-Hooper What price should the United States – or any leading power – be willing to pay to prevent nuclear proliferation? For most realists, who believe nuclear weapons possess largely defensive qualities, the price should be small indeed. While additional nuclear states might not be welcomed, their appearance should not be cause for undue alarm. Such equanimity would be especially warrantedWORKING if the state in question PAPER: lacked DO other attributesNOT CITE of power. OR Nuclear acquisition should certainly notCIRCULATE trigger thoughts of WITHOUT preventive militar PERMISSIONy action, a phenomena typically associated with dramatic shifts in the balance of power. The historical record, however, tells a different story. Throughout the nuclear age and despite dramatic changes in the international system, the United States has time and again considered aggressive policies, including the use of force, to prevent the emergence of nuclear capabilities by friend and foe alike. What is even more surprising is how often this temptation has been oriented against what might be called “feeble” states, unable to project other forms of power. The evidence also reveals that the reasons driving this preventive thinking often had more to do with concerns over the systemic consequences of nuclear proliferation, and not, as we might expect, the dyadic relationship between the United States and the proliferator. Factors 1 typically associated with preventive motivations, such as a shift in the balance of power or the ideological nature of the regime in question, were largely absent in high-level deliberations. -

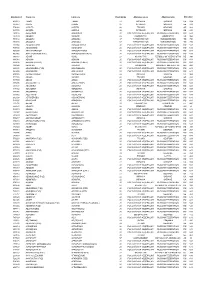

FÁK Állomáskódok

Állomáskód Orosz név Latin név Vasút kódja Államnév orosz Államnév latin Államkód 406513 1 МАЯ 1 MAIA 22 УКРАИНА UKRAINE UA 804 085827 ААКРЕ AAKRE 26 ЭСТОНИЯ ESTONIA EE 233 574066 ААПСТА AAPSTA 28 ГРУЗИЯ GEORGIA GE 268 085780 ААРДЛА AARDLA 26 ЭСТОНИЯ ESTONIA EE 233 269116 АБАБКОВО ABABKOVO 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 737139 АБАДАН ABADAN 29 УЗБЕКИСТАН UZBEKISTAN UZ 860 753112 АБАДАН-I ABADAN-I 67 ТУРКМЕНИСТАН TURKMENISTAN TM 795 753108 АБАДАН-II ABADAN-II 67 ТУРКМЕНИСТАН TURKMENISTAN TM 795 535004 АБАДЗЕХСКАЯ ABADZEHSKAIA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 795736 АБАЕВСКИЙ ABAEVSKII 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 864300 АБАГУР-ЛЕСНОЙ ABAGUR-LESNOI 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 865065 АБАГУРОВСКИЙ (РЗД) ABAGUROVSKII (RZD) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 699767 АБАИЛ ABAIL 27 КАЗАХСТАН REPUBLIC OF KAZAKHSTAN KZ 398 888004 АБАКАН ABAKAN 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 888108 АБАКАН (ПЕРЕВ.) ABAKAN (PEREV.) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 398904 АБАКЛИЯ ABAKLIIA 23 МОЛДАВИЯ MOLDOVA, REPUBLIC OF MD 498 889401 АБАКУМОВКА (РЗД) ABAKUMOVKA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 882309 АБАЛАКОВО ABALAKOVO 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 408006 АБАМЕЛИКОВО ABAMELIKOVO 22 УКРАИНА UKRAINE UA 804 571706 АБАША ABASHA 28 ГРУЗИЯ GEORGIA GE 268 887500 АБАЗА ABAZA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 887406 АБАЗА (ЭКСП.) ABAZA (EKSP.) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 -

The Air Force and the Cold

THE AIR FORCE A N D T H E COLD WA R A P I C T O R I A L H I S T O RY COVER AIR FORCE ASSOCIATION The Air Force and the Cold War 1 The Air Force Association THE AIR FORCE The Air Force Association (AFA) is an independent, nonprofit civilian organization A N D T H E promoting public understanding of aerospace power and the pivotal role it plays in the se- curity of the nation. AFA publishes Air Force Magazine, sponsors national symposia, and disseminates information through outreach programs of its affiliate, the Aerospace Educa- tion Foundation. Learn more about AFA by visiting us on the Web at www.afa.org. COLD WA R The Aerospace Education Foundation The Aerospace Education Foundation (AEF) is dedicated to ensuring America’s aerospace excellence through education, schol- arships, grants, awards, and public awareness programs. The foundation also publishes a series of studies and forums on aerospace and national security. The Eaker Institute is the public policy and research arm of AEF. AEF works through a network of thousands of Air Force Association members and more than 200 chapters to distribute educational material to schools and concerned citizens. An example of this includes “Visions of Exploration,” an AEF/USA Today multidis- ciplinary science, math, and social studies program. To find out how you can support aerospace excellence, visit us on the Web at www.aef.org. © 2005 The Air Force Association Published by Aerospace Education Foundation 1501 Lee Highway Arlington VA 22209-1198 Tel: (703) 247-5839 Produced by the staff of Air Force Magazine Fax: (703) 247-5853 Design by Darcy Harris THE AIR FORCE A N D T H E COLD WA R A P I C T O R I A L H I S T O RY AIR FORCE ASSOCIATION DECEMBER 2005 By John T. -

'The Cuban Question' and the Cold War in Latin America, 1959-1964

‘The Cuban question’ and the Cold War in Latin America, 1959-1964 LSE Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/101153/ Version: Published Version Article: Harmer, Tanya (2019) ‘The Cuban question’ and the Cold War in Latin America, 1959-1964. Journal of Cold War Studies, 21 (3). pp. 114-151. ISSN 1520-3972 https://doi.org/10.1162/jcws_a_00896 Reuse Items deposited in LSE Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the LSE Research Online record for the item. [email protected] https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/ The “Cuban Question” and the Cold War in Latin America, 1959–1964 ✣ Tanya Harmer In January 1962, Latin American foreign ministers and U.S. Secretary of State Dean Rusk arrived at the Uruguayan beach resort of Punta del Este to debate Cuba’s position in the Western Hemisphere. Unsurprisingly for a group of representatives from 21 states with varying political, socioeconomic, and geo- graphic contexts, they had divergent goals. Yet, with the exception of Cuba’s delegation, they all agreed on why they were there: Havana’s alignment with “extra-continental communist powers,” along with Fidel Castro’s announce- ment on 1 December 1961 that he was a lifelong Marxist-Leninist, had made Cuba’s government “incompatible with the principles and objectives of the inter-American system.” A Communist offensive in Latin America of “in- creased intensity” also meant “continental unity and the democratic institu- tions of the hemisphere” were “in danger.”1 After agreeing on these points, the assembled officials had to decide what to do about Cuba. -

TUESDAY, M Y 1, 1962 the President Met with the Following of The

TUESDAY, MAYMYI,1, 1962 9:459:45 -- 9:50 am The PrePresidentsident met with the following of the Worcester Junior Chamber of CommeCommerce,rce, MasMassachusettssachusetts in the Rose Garden: Don Cookson JJamesarne s Oulighan Larry Samberg JeffreyJeffrey Richard JohnJohn Klunk KennethKenneth ScScottott GeorgeGeorge Donatello EdwardEdward JaffeJaffe RichardRichard MulhernMulhern DanielDaniel MiduszenskiMiduszenski StazrosStazros GaniaGaniass LouiLouiss EdmondEdmond TheyThey werewere accorrpaccompaniedanied by CongresCongressmansman HaroldHarold D.D. DonohueDonohue - TUESDAY,TUESbAY J MAY 1, 1962 8:45 atn LEGISLATIVELEGI~LATIVE LEADERS BREAKFAST The{['he Vice President Speaker John W. McCormackMcCortnack Senator Mike Mansfield SenatorSenato r HubertHube rt HumphreyHUInphrey Senator George SmatherStnathers s CongressmanCongresstnan Carl Albert CongressmanCongresstnan Hale BoggBoggs s Hon. Lawrence O'Brien Hon. Kenneth O'Donnell0 'Donnell Hon. Pierre Salinger Hon. Theodore Sorensen 9:35 amatn The President arrived in the office. (See insert opposite page) 10:32 - 10:55 amatn The President mettnet with a delegation fromfrotn tktre Friends'Friends I "Witness for World Order": Henry J. Cadbury, Haverford, Pa. Founder of the AmericanAtnerican Friends Service CommitteeCOtntnittee ( David Hartsough, Glen Mills, Pennsylvania Senior at Howard University Mrs. Dorothy Hutchinson, Jenkintown, Pa. Opening speaker, the Friends WitnessWitnes~ for World Order Mr. Samuel Levering, Arararat, Virginia Chairman of the Board on Peace and.and .... Social Concerns Edward F. Snyder, College Park, Md. Executive Secretary of the Friends Committe on National Legislation George Willoughby, Blackwood Terrace, N. J. Member of the crew of the Golden Rule (ship) and the San Francisco to Moscow Peace Walk (Hon. McGeorgeMkGeorge Bundy) (General Chester V. Clifton 10:57 - 11:02 am (Congre(Congresswomansswoman Edith Green, Oregon) OFF TRECO 11:15 - 11:58 am H. -

MORI Docid : 9625

"'!;-·· - -~ -:;.:.:·,>;~T:-:'~~···o; MORI DociD : 9625 (b) (1) (b) (3) AEPROVED FOR RELEASE DATE : JUN 2003 MOR ID: 0 T.QP SECRET - (b) ( l) OFFICE OF SPECIAL ACTIVITIES (b) ( ) 1954-1968 CHRONOLOGY 1954 1 Feb Mr. Richard M. Bissell, Jr., is named Special Assistant to the Director for Planning and Coord ination (SA/PC/DCI) by the Director of Central Intelligence, Mr. Allen W. Dulles. 1 Jul SA/PC/DCI absorbs the Office of Intelligence Co ordination (except the Intelligence Advisory Committee Secretariat) and the Assistant Director for Intelligence Coordination, Mr. James Q. Reber, joins the Planning and Coordination Staff as Mr. Bissell's Assistant. 4 Jul The Hoover Commission on Organization of the Executive Branch establishes a task force under General Mark Clark to investigate CIA and answer Congressional criticism of the Agency. A Special Study Group, chaired by General James H. Doolittle, is assigned to investigate CIA's covert activities. 30 Sep The Doolittle group reports on its investigation of CIA and expresses the belief that every known tech nique should be used, and new ones developed, to increase U.S. intelligence by high altitud& photo graphic reconnaissance and other means. 9 Oct A Technological Capabilities Panel of the Office of Defense Mobilization's "Surprise Attack Committee" under Dr. James R. Killian is set up with Dr. Edwin H. Land, President of Polaroid, as Chairman. 5 Nov The Technological Capabilities Panet, Project 3, in a letter to the DCI, proposes a program of photo reconnaissance flights over the USSR and recommends that CIA, with Air Force assistance, undertake such a program. -

The Third Battle

NAVAL WAR COLLEGE NEWPORT PAPERS 16 The Third Battle Innovation in the U.S. Navy's Silent Cold War Struggle with Soviet Submarines N ES AV T A A L T W S A D R E C T I O N L L U E E G H E T R I VI IBU OR A S CT MARI VI Owen R. Cote, Jr. Associate Director, MIT Security Studies Program The Third Battle Innovation in the U.S. Navy’s Silent Cold War Struggle with Soviet Submarines Owen R. Cote, Jr. Associate Director, MIT Security Studies Program NAVAL WAR COLLEGE Newport, Rhode Island Naval War College The Newport Papers are extended research projects that the Newport, Rhode Island Editor, the Dean of Naval Warfare Studies, and the Center for Naval Warfare Studies President of the Naval War College consider of particular Newport Paper Number Sixteen interest to policy makers, scholars, and analysts. Candidates 2003 for publication are considered by an editorial board under the auspices of the Dean of Naval Warfare Studies. President, Naval War College Rear Admiral Rodney P. Rempt, U.S. Navy Published papers are those approved by the Editor of the Press, the Dean of Naval Warfare Studies, and the President Provost, Naval War College Professor James F. Giblin of the Naval War College. Dean of Naval Warfare Studies The views expressed in The Newport Papers are those of the Professor Alberto R. Coll authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Naval War College or the Department of the Navy. Naval War College Press Editor: Professor Catherine McArdle Kelleher Correspondence concerning The Newport Papers may be Managing Editor: Pelham G. -

Fixed Sonar Systems the History and Future of The

THE SUBMARINE REVIEW FIXED SONAR SYSTEMS THE HISTORY AND FUTURE OF THE UNDEWATER SILENT SENTINEL by LT John Howard, United States Navy Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, California Undersea Warfare Department Executive Summary One of the most challenging aspects of Anti-Submarine War- fare (ASW) has been the detection and tracking of submerged contacts. One of the most successful means of achieving this goal was the Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS) developed by the United States Navy in the early 1950's. It was designed using breakthrough discoveries of the propagation paths of sound through water and intended to monitor the growing submarine threat of the Soviet Union. SOSUS provided cueing of transiting Soviet submarines to allow for optimal positioning of U.S. ASW forces for tracking and prosecution of these underwater threats. SOSUS took on an even greater national security role with the advent of submarine launched ballistic missiles, ensuring that U.S. forces were aware of these strategic liabilities in case hostilities were ever to erupt between the two superpowers. With the end of the Cold War, SOSUS has undergone a number of changes in its utilization, but is finding itself no less relevant as an asset against the growing number of modern quiet submarines proliferating around the world. Introduction For millennia, humans seeking to better defend themselves have set up observation posts along the ingress routes to their key strongholds. This could consist of something as simple as a person hidden in a tree, to extensive networks of towers communicating 1 APRIL 2011 THE SUBMARINE REVIEW with signal fires. -

The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense : Robert S. Mcnamara

The Ascendancy of the Secretary ofJULY Defense 2013 The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara 1961-1963 Special Study 4 Historical Office Office of the Secretary of Defense Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 4 The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara 1961-1963 Cover Photo: Secretary Robert S. McNamara, Gen. Maxwell D. Taylor, and President John F. Kennedy at the White House, January 1963 Source: Robert Knudson/John F. Kennedy Library, used with permission. Cover Design: OSD Graphics, Pentagon. Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 4 The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara 1961-1963 Special Study 4 Series Editors Erin R. Mahan, Ph.D. Chief Historian, Office of the Secretary of Defense Jeffrey A. Larsen, Ph.D. President, Larsen Consulting Group Historical Office Office of the Secretary of Defense July 2013 ii iii Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 4 The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense Contents This study was reviewed for declassification by the appropriate U.S. Government departments and agencies and cleared for release. The study is an official publication of the Office of the Secretary of Defense, Foreword..........................................vii but inasmuch as the text has not been considered by the Office of the Secretary of Defense, it must be construed as descriptive only and does Executive Summary...................................ix not constitute the official position of OSD on any subject. Restructuring the National Security Council ................2 Portions of this work may be quoted or reprinted without permission, provided that a standard source credit line in included. -

TULA М4 Rail М2 М2

CATALOGUE OF INDUSTRIAL PRODUCTS EXPORTED BY THE TULA REGION 1 CATALOGUE CONTENTS INFORMATION 3 MECHANICAL ENGINEERING 6 METALLURGICAL INDUSTRY 16 CHEMICAL INDUSTRY 25 LIGHT INDUSTRY 36 FOOD INDUSTRY 48 CONTACT INFORMATION 62 2 CATALOGUE CONTENTS “THE FOREIGN TRADE TURNOVER STRUCTURE NOW MEETS ALL THE CRITERIA FOR ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND IS EXPORT-ORIENTED. WE NEED TO INCREASE THE VOLUME OF EXPORTS AND FIND NEW SALES MARKETS.” Governor of the Tula Region Alexei Dyumin 3 TULA REGION TRADE WITH MAJOR TRADING PARTNERS: 126 USA, CHINA, COUNTRIES BELARUS, ALGERIA, TURKEY, UAE, GERMANY 36,2% Chemical industry products and rubber 28,1% Other goods 6,8% Mechanical engineering products 5% Foods and raw materials Population Total area Tula Novomoskovsk 23,9% Metals and metal 1 466 127 25 700 550,8 125,2 products people sq. km thousand people thousand people EXPORT STRUCTURE EXPORT 4 TULA REGION MOSCOW М2 MOSCOW REGION TWO FEDERAL HIGHWAYS • M2 ‘Crimea’ М4 Zaokskiy Rail • M4 ‘Don’ KALUGA REGION Aleksin RAILWAY ROUTES Yasnogorsk • MOSCOW–KHARKOV–SIMFEROPOL, Venoyv • MOSCOW–DONBAS; TULA TRANSPORT ROUTES Dubna Suvorov Novomoskovsk RYAZAN REGION • Tula – M4 ‘Don’ Transcaucasia, Western Asia (part of the Chekalin Shchyokino Uzlovaya Kimovsk European route E 115) Odoyev Kireyevsk • Tula – M2 ‘Crimea’ Europe (part of the European route E105) Belyov Arsenyevo Bogoroditsk Plavsk Tyoploye Volovo AIR TRAFFIC: • Sheremetyevo (210 km) – more than 230 domestic and М2 Chern Kurkino international destinations • Domodedovo (170 km) – 194 destinations Arkhangelskoye LIPETSK • Vnukovo (180 km) – more than 200,000 domestic and REGION international destinations ORYOL REGION Yefremov • Kaluga Airport (110 km) – 9 domestic destinations М4 5 MECHANICAL ENGINEERING THE TULAMASHZAVOD PRODUCTION ASSOCIATION The TULAMASHZAVOD Production Association is a major holding that includes the parent TULAMASHZAVOD Joint-Stock Company and twenty subsidiaries that focus equally on both the manufacturing of products for the defence industry and civilian products. -

ANNEX J Exposures and Effects of the Chernobyl Accident

ANNEX J Exposures and effects of the Chernobyl accident CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION.................................................. 453 I. PHYSICALCONSEQUENCESOFTHEACCIDENT................... 454 A. THEACCIDENT........................................... 454 B. RELEASEOFRADIONUCLIDES ............................. 456 1. Estimation of radionuclide amounts released .................. 456 2. Physical and chemical properties of the radioactivematerialsreleased ............................. 457 C. GROUNDCONTAMINATION................................ 458 1. AreasoftheformerSovietUnion........................... 458 2. Remainderofnorthernandsouthernhemisphere............... 465 D. ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIOUR OF DEPOSITEDRADIONUCLIDES .............................. 465 1. Terrestrialenvironment.................................. 465 2. Aquaticenvironment.................................... 466 E. SUMMARY............................................... 466 II. RADIATIONDOSESTOEXPOSEDPOPULATIONGROUPS ........... 467 A. WORKERS INVOLVED IN THE ACCIDENT .................... 468 1. Emergencyworkers..................................... 468 2. Recoveryoperationworkers............................... 469 B. EVACUATEDPERSONS.................................... 472 1. Dosesfromexternalexposure ............................. 473 2. Dosesfrominternalexposure.............................. 474 3. Residualandavertedcollectivedoses........................ 474 C. INHABITANTS OF CONTAMINATED AREAS OFTHEFORMERSOVIETUNION............................ 475 1. Dosesfromexternalexposure