Lawler, the Dance in Jest, 1963

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Download

• ,.....-,-, ..........-- .... r(, n f / 1i' \) I '1 Cl -~-;:, .,-" ( 11 ,,/ 1C ( je: r.,'T J ! 1 ')(1' 1;) r I' , /. ,,' t ,r (' ~" , TI )' T Beiträge zur Alten Geschichte, Papyrologie und Epigraphik TYCHE Beiträge zur Alten Geschichte, Papyrologie und Epigraphik Band 19 2004 HOL % HAU 5 E N Herausgegeben von: Gerhard Dobesch, Bemhard Palme, Peter Siewert und Ekkehard Weber Gemeinsam mit: Wolfgang Hameter und Hans Taeuber Unter Beteiligung von: Reinhold Bichler, Herbert Graßl, Sigrid Jalkotzy und Ingomar Weiler Redaktion: Franziska Beutler, Sandra Hodecek, Georg Rehrenböck und Patrick Sänger Zuschriften und Manuskripte erbeten an: Redaktion TYCHE, c/o Institut für Alte Geschichte und Altertumskunde, Papyrologie und Epigraphik, Universität Wien, Dr. Karl Lueger-Ring 1, A-lOlO Wien. Beiträge in deutscher, englischer, französischer, italienischer und lateinischer Sprache werden angenommen. Bei der Redaktion einlangende wissenschaftliche Werke werden angezeigt. Auslieferung: Holzhausen Verlag GmbH, Holzhausenplatz ], A-] 140 Wien maggoschitz@holzhausen .at Gedruckt auf holz- und säurefreiem Papier. Umschlag: IG U2 2127 (Ausschnitt) mit freundlicher Genehmigung des Epigraphischen Museums in Athen, Inv.-Nr. 8490, und P.Vindob.Barbara 8. © 2005 by Holzhausen Verlag GmbH, Wien Bibliografische Information Der Deutschen Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Intemet über http://clnb.dclb.de abrufbar Eigentümer und Verleger: Holzhausen Verlag GmbH, Holzhausenplatz ], A-1140 Wien Herausgeber: Gerhard Dobesch, Bernhard Palme, Peter Siewert und Ekkehard Weber, c/o Institut für Alte Geschichte und Altertumskunde, Papyrologie und Epigraphik, Universität Wien, Dr. Kar! Lueger-Ring 1, A-lOIO Wien. e-mail: [email protected]@univie.ac.at Hersteller: Holzhausen Druck & Medien GmbH, Holzhausenplatz 1, A-1140 Wien Verlagsort: Wien. -

Dewald 1987. Carolyn Dewald, “Narrative Surface and Authorial

DEWALD, CAROLYN, Narrative Surface and Authorial Voice in Herodotus' "Histories" , Arethusa, 20:1/2 (1987:Spring/Fall) p.147 NARRATIVE SURFACE AND AUTHORIAL VOICE IN HERODOTUS' HISTORIES CAROLYN DEWALD It is a topos nowadays that an author does not just construct his text but also encodes into it a narrative contract: he writes into the text the rules by which his audience is to read it, how we are to under stand his performance as author and our own responsibilities and legitimate pleasures as readers. 1 Judged by the standards of later historical prose, the narrative contract that Herodotus establishes be tween himself, the author, and ourselves, his readers, is a peculiar one. Its rules are very odd indeed. Here I would like to explore two aspects of those rules: the construction of the narrative surface and of the authorial "I" within it. Both these aspects of Herodotus' rhetoric have generally been evaluated against the standard practices of history writing. But if we look at Herodotus' narrative surface and authorial voice on their own terms, the contract they suggest is not (at least in some essentials) a historical one. The Herodotus I would like to pro pose here is a heroic warrior. Like Menelaus on the sands of Egypt, he struggles with a fearsome beast - and wins. The antagonist that He rodotus struggles with is, like many mythic beasts, a polymorphously fearsome oddity; it consists of the logos, or collection of logoi, that comprise the narrative of the Histories. What Herodotus, like Mene laus, wants from his contest is accurate information. -

Hyperboreus Studia Classica

HYPERBOREUS STUDIA CLASSICA nausˆ d' oÜte pezÕj „èn ken eÛroij ™j `Uperboršwn ¢gîna qaumast¦n ÐdÒn (Pind. Pyth. 10. 29–30) EDITORES NINA ALMAZOVA SOFIA EGOROVA DENIS KEYER NATALIA PAVLICHENKO ALEXANDER VERLINSKY PETROPOLI Vol. 21 2015 Fasc. 1 BIBLIOTHECA CLASSICA PETROPOLITANA VERLAG C. H. BECK MÜNCHEN Сonspectus СONSPECTUS DIRK L. COUPRIE The Paths of the Celestial Bodies According to Anaximenes . 5 MARIA KAZANSKAYA A Ghost Proverb in Herodotus (6. 129. 4)? . 33 З. А. БАРЗАХ Использование разговорных идиом в трагедиях Софокла . 53 SERGEY V. K ASHAEV, NATALIA PAVLICHENKO Letter on an Ostracon From the Settlement of Vyshesteblievskaya-3 . 61 ANTONIO CORSO Retrieving the Aphrodite of Hermogenes of Cythera . 80 ARSENIJ VETUSHKO-KALEVICH Batăvi oder Batāvi? Zu Luc. Phars. I, 430–440 . 90 ARCHAEOLOGICA DMITRIJ CHISTOV Investigations on the Berezan Island, 2006–2013 (Hermitage Museum Archaeological Mission) . 106 VLADIMIR KHRSHANOVSKIY An Investigation of the Necropoleis of Kytaion and the Iluraton Plateau (2006–2013) . 111 OLGA SOKOLOVA The Nymphaion expedition of the State Hermitage Museum (2006–2013) 121 ALEXANDER BUTYAGIN Excavations at Myrmekion in 2006–2013 . 127 Статьи сопровождаются резюме на русском и английском языке Summary in Russian and English 3 4 Сonspectus MARINA JU. VAKHTINA Porthmion Archaeological Expedition of the Institute for History of Material Culture, RAS – Institute of Archaeology, NASU . 135 SERGEY V. K ASHAEV The Taman Detachment of the Bosporan Expedition of IIMK RAS, 2006–2013 . 140 YURIJ A. VINOGRADOV Excavations at the Settlement of Artyushchenko–I (Bugazskoe) on the Taman Peninsula . 157 VLADIMIR GORONCHAROVSKIY The Townsite of Semibratneye (Labrys) Results of Excavations in 2006–2009 . 161 DISPUTATIONES SANDRA FAIT Peter Riedlberger, Domninus of Larissa, Encheiridion and Spurious Works. -

The Mysterious Expedition of Thrasybulus of Miletus

Studia Antiqua et Archaeologica 23(2): 249–255 The mysterious expedition of Thrasybulus of Miletus Sergey M. ZHESTOKANOV1 Abstract. A cursory mention of a mysterious expedition against Sicyon, mounted by Thrasybulus, the tyrant of Miletus, can be found in Frontinus’ “Strategemata”. The author of the present article is of the opinion that in this way Thrasybulus was helping his ally Periander, the tyrant of Corinth. The probable aim of Periander’s military campaign was to reinstate the exiled Isodemus as tyrant of Sicyon and to include the Sicyonians’ territory in Corinth’ sphere of influence. Rezumat. O mențiune superficială a expediției misterioase împotriva cetății Sicyon, dusă de Thrasybulus, tiranul Miletului, este întâlnită în „Strategemata” lui Frontinus. Autorul acestui articol este de părere că în acest mod Thrasybulus îl ajuta pe aliatul său Periander, tiranul Corintului. Scopul probabil al campaniei militare a lui Periander era acela de a-l reinstala pe exilatul Isodemos ca tiran al Sicyon-ului și de a include cetatea în sfera de influență a Corintului. Keywords: Greece, Corinth, Sicyon, Archaic age, tyranny. In his treatise “Strategemata”, Sextus Julius Frontinus makes a reference to a rather mysterious expedition against Sicyon, led by Thrasybulus, the tyrant of Miletus in the 7th century BC: Thrasybulus, dux Milesiorum, ut portum Sicyoniorum occuparet, a terra subinde oppidanos temptavit et illo, quo lacessebantur, conversis hostibus classe in /ex/ spectata portum cepit. (Thrasybulus, leader of the Milesians, in his efforts to seize the harbour of the Sicyonians, made repeated attacks upon the inhabitants from the land side. Then, when the enemy directed their attention to the point where they were attacked, he suddenly seized the harbour with his fleet) (III, 9, 7). -

Crossing the Styx

® A publication of the American Philological Association Vol. 5 • Issue 2 • Fall 2006 CROSSING THE STYX: THE Shadow Government: AFTERLIFE OF THE AFTERLIFE HBO’s Rome by Alison Futrell by Margaret Drabble ince the box office success of Gladiator hades from the underworld walk in also the name of a Finnish pop group, unexpected places in contempo- founded in 1992, Styx is an American S(2000), television networks have been S trying to find a way to bring the glory and rary culture, and of late I’ve been pop group, Artemesia’s Ashes is a Russ- encountering them everywhere. New ian pop group, and Tartarus is an inter- corruption of ancient Rome to the small moons are still named after old gods. net war game. Charon has also given his screen. HBO’s long-anticipated miniseries The International Astronomical Union name to organizations like Charon Rome (2005) succeeds hugely, presenting approves this practice and discourages Cemetery Management, which boasts a richly visualized and sophisticated work astronomers from calling asteroids after that it has “user friendly software for the their pets or their wives. Pluto’s moon, death care industry.” The imagery of that takes the ancient evidence seriously. discovered in 1978, was named Charon, the ancient underworld has a long and Focusing on the period between 52 and and on All Souls Eve 2005, I heard that adaptable afterlife. 44 B.C., the series dramatizes the deterio- the discovery of two new moons of And classical learning infiltrates con- ration of the Republic into civil war and the Pluto had just been announced. -

Hippokleides, the 'Dance', and the Panathenaia

Hippokleides, the ‘Dance’, and the Panathenaia Brian M. Lavelle IPPOKLEIDES, the son of Teisandros and of the clan Philaidai, is an intriguing but obscure figure in the H history of Athens in the early sixth century BCE.1 There are only two testimonia of consequence about him, one quite brief, the other much longer. The briefer one states that he was archon of Athens when the Greater Panathenaia was established and has been taken to imply that he was the festi- val’s originator. The longer, less substantive testimonium is far more entertaining. It is of course Herodotos’ famous story of the ‘marriage of Agariste’, the daughter of Kleisthenes, tyrant of Sikyon (6.126–130). For the greater part of the story, Hip- pokleides seems to be the star of the show: a luminous paragon of Archaic Greek noblesse, he is outstanding among the many suitors at Sikyon vying for the girl’s hand, demonstrating ἀν- δραγαθία and other qualities over nearly a year. Yet, for all of that and his year-long probation, things turn out quite badly for Hippokleides—and all at once. A shocking display of vul- garity at the exact moment when victory is imminent sinks him and his chances utterly. Such a catastrophic lapse in behavior and judgment is surprisingly inconsistent with Hippokleides’ chronically demonstrated excellence and moderation. The stunning reversal is in fact improbable—it is as if ‘Hippokleides’ is two different persons—and raises doubts about the story, to which may be added those created by its obvious folktale 1 Cf. H. Swoboda, “Hippokleides (1),” RE 8 (1913) 1772–1773; J. -

Introduction: Clio and Thalia

Histos Supplement ( ) – INTRODUCTION: CLIO AND THALIA Emily Baragwanath and Edith Foster he sisters Clio and Thalia at first sight possess not family likeness, but starkly dissimilar features: the one serious-minded and noble, a worshipper at the T 1 altar of truth; the other, a lewd mistress of distortions and falsification who peddles base laughter. Yet to the observer who lingers to take a closer look, their features disclose a8nities that shed light on both genres. The papers collected in this supplementary volume of Histos move beyond our well-established practice of using Attic comedy and historiography to clarify each other, and set them side by side to reflect upon how they responded and related to each other in ancient times. 2 Attic comedy and fifth-century historiography shared important themes and aims. 3 Perhaps most conspicuously, comedy taught about historical individuals and contempo- rary issues—famous political leaders, such as Pericles or Cleon, the sophists, the new education, generation clash, the foibles of the democracy, the courts, of policy toward the war—that connected with Thucydides’ account of, and 1 Cf. Lucian’s characterisation of the ideal historian. 2 Strasburger (? ) reviews the presence of comic elements in Greek historiography from the Classical to Hellenistic periods, and remarks ( ) on how little historiography owes to comedy. Cf. Will ( B) ?. The present volume is concerned not with ‘influences’ of one on the other, but with their relationships and a8nities. 3 Tragic elements in the works of the ancient Greek historians have drawn a good deal more scholarly attention than comic ones, e.g. -

Humor and Ethnography in Herodotus' Histories

HUMOR AND ETHNOGRAPHY IN HERODOTUS’ HISTORIES Mark Christopher Mash A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classics. Chapel Hill 2010 Approved by: Emily Baragwanath, Advisor Peter M. Smith, Reader Owen E. Goslin, Reader Cecil W. Wooten, Reader Fred S. Naiden, Reader ©2010 Mark Christopher Mash ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT MARK CHRISTOPHER MASH: Humor and Ethnography in Herodotus’ Histories (Under the direction of Emily Baragwanath) This dissertation examines the role of humor in Herodotus’ Histories. I argue that Herodotus’ humor is best understood in the context of his ethnography, and base my analyses on the thoughts of ancient and modern writers on humor. In particular, I incorporate anthropological perspectives on humor, and most notably ethnic humor. In chapter one, I establish the groundwork for later discussions by situating my work in the context of previous ancient and modern analyses of humor. In chapter two, I examine derision and witty retorts, starting first with Herodotus’ own ridicule of mapmakers in 4.36.2. In chapter three, I discuss the role of humorous deception in the Histories. In this interplay of humor and deception, I examine three main types: tricks that are reveled in by the instigator, tricks that are uncovered, and tricks that turn deadly. In chapter four, I take up the relationship between didacticism and humor, and show how it appears as an oblique tool by which wise advisors are able to challenge the rigidity of their recipient’s thinking. -

"Women in Herodotus' "Histories"."

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses "Women in Herodotus' "Histories"." Georgiou, Irene-Evangelia How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Georgiou, Irene-Evangelia (2002) "Women in Herodotus' "Histories".". thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa43005 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ Women in H erodotus’ H is t o r ie s Irene-Evangelia Georgiou Submitted to the University of Wales in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Wales Swansea 2 0 0 2 ProQuest Number: 10821395 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

List of Characters

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-17256-1 – Aristophanes: Clouds John Claughton and Judith Affleck Excerpt More information List of characters STREPSIADES an ordinary Athenian PHEIDIPPIDES his son STUDENT SOCRATES CHORUS Clouds STRONG the stronger argument (Right) WEAK the weaker argument (Wrong) PASIAS first creditor AMYNIAS second creditor OTHER STUDENTS 1 © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-17256-1 – Aristophanes: Clouds John Claughton and Judith Affleck Excerpt More information Setting the scene: the problem (1–132) Greek tragedy is populated with the heroic figures of a remote and mythical past, like Oedipus, Agamemnon, Electra and Antigone, with occasional appearances by the gods. Greek comedy shared the same stage and the same festivals (see pp. 120–3), but it is very different. It is about the ordinary Athenian, usually faced with a down-to-earth problem for which he finds an extraordinary solution. So, the ‘hero’ of Greek comedy is, for the audience, ‘one of us’. Strepsiades has a number of ordinary, even timeless, problems, including a disobedient and extravagant son and not enough money to go round. The play opens with a long soliloquy (1–78), occasionally interrupted, in which we hear Strepsiades worrying about his financial difficulties. 1 Strepsiades Many of Aristophanes’ names are chosen for a reason. Strepsiades is related to the Greek word for turning and twisting. We first see Strepsiades tossing and turning on his bed (see also 36, ‘Initiation’, p. 20, 434, 1455). 2 what a night! In an open-air theatre it isn’t possible to convey darkness, so Strepsiades has to make it clear what time of day it is. -

Metics and Identity in Democratic Athens

METICS AND IDENTITY IN DEMOCRATIC ATHENS By MATTHEW JOHN KEARS A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Institute of Archaeology and Antiquity College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham March 2013 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis investigates the metics, or resident aliens, in democratic Athens and how they affected ideas of identity, with a particular focus on the fourth century BC. It looks at definitions of the metics and how the restrictions and obligations which marked their status operated; how these affected their lives and their image, in their own eyes and those of the Athenians; how the Athenians erected and maintained a boundary of status and identity between themselves and the metics, in theory and in practice; and how individuals who crossed this boundary could present themselves and be characterised, especially in the public context of the lawcourts. The argument is that the metics served as a contradiction of and challenge to Athenian ideas about who they were and what made them different from others. -

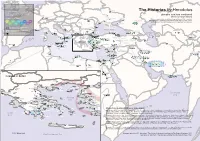

The Histories by Herodotus Chapter, a Hexagon with Light Border Is Drawn Near the Location the Character Hylaea Comes From

For each location mentioned in a chapter, a hexagon with dark border is drawn near that location. Dnieper For each character mentioned in a Gelonus The Histories by Herodotus chapter, a hexagon with light border is drawn near the location the character Hylaea comes from. placable locations mentioned Celts Danube Pyrene three or more times Chapter Color Scale: Gerrians Carpathian Mountains Tanaïs Where a region is dominated by a large settlement (like a capital), Far Scythia the settlement is generally used instead of the region to save space. I III V VII IX Some names in crowded locations on the map have been left out. Dacia Tyras Borysthenes II IV VI VIII Cremnoi Istros the place or the people was Illyria Scythian Neapolis mentioned explicitly Getae Marseille Odrysians Black Sea a character from nearby was Aléria Italy Mesambria Caucasus Massagetae Phasis mentioned Paeonia Sinop Pteria Caere Brygians Apollonia city or mountain location Mt. Haemus Caspian Byzantium Colchis Sea Sardinia Taranto Thyrea Sogdia Siris Velia Messapii Terme River Cyzicus Gordium Sybaris Crotone Cappadocia Sardis Armenia Messina Segesta Rhegium Greece Tigris Caspiane Tartessos Gela Pamphylia Parthia Carthage Selinunte Syracuse Milas Kaunos Cilicia Telmessos Nineveh Kamarina Lindos Posideion Xanthos Salamis Euphrates Kourion Ecbatana Amathus Gandhara Cyprus Tyre Sidon Cyrene Lotophagi Babylon Susa Barca Garamantes Macai Saïs Ienysos Heliopolis Petra Atlas Persepolis Asbystai Awjila Memphis Ammonians Egyptian Thebes Greece in detail Elephantine BC invasion b Myrkinos 480 y Xe rxes Red Macedonia Abdera Cicones Eïon Doriscus Sea Therma The Nile Olynthus Akanthos Thasos Cardia Sestos Pieria Vardar Samothrace Lampsacus Chalcidice Sane Imbros Abydos Pindus Mt.