The Moghal Empire Xvi PREFACE Published in the Original Text and in Translation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study on Muslim Jarral Rajputs of Rajouri:A Review

International Journal For Technological Research In Engineering Volume 6, Issue 10, June-2019 ISSN (Online): 2347 - 4718 A STUDY ON MUSLIM JARRAL RAJPUTS OF RAJOURI:A REVIEW Salma Shahzad1, Dr. Rama Singh2 Department of Sociology, Barkatullah University, Bhopal. M.P. Abstract: The present study is an attempt to explore the Srinagar Division and Kargil and Leh in Ladakh Region. The status of muslim jarral Rajputs hailing from Rajouri Siachen Glacier, although under Indian military control, does district, Jammu and Kashmir state. The state is divided into not lie under the administration of the state of Jammu and three sub-divisions i.e. Jammu, Srinagar (Kashmir) and Kashmir. Jammu and Kashmir have a Muslim majority Ladakh, mountain of Pir panjal range separates Jammu population. The population living in the Valley of Kashmir is region from Kashmir. Since time immemorial Rajouri was primarily homogeneous, despite the religious divide between the land of Rajas. Different Rajput Rajas in different times Muslims 94%, Hindus 4%, and Sikhs 2%, the state has large had ruled Rajouri and presently fairly a good number of communities of Buddhists Hindus (inclusive of Megh Rajputs are also settled in the vicinity of Rajouri. Rajputs Bhagats) and Sikhs. In Jammu, Hindus constitute 65% of the still enjoy high influence and reputation in socio-economic, population, Muslim 31% and Sikh 4%; in Ladakh, Buddhists cultural, political and traditional dominance etc., in the constitute about 46% of the population, the remaining being entire region. Jarral Rajputs claim their origin from the Muslims. The people of Ladakh are of Indo-Tibetan origin. Rajas of Rajouri; they are fairly widely distributed in the The total population of the Jammu and Kashmir according to region. -

Later Mughals;

1 liiu} ijji • iiiiiiimmiiiii ii i] I " • 1 1 -i in fliiiiiiii LATER MUGHALS WILLIAM IRVINE, i.c.s. (ret.), Author of Storia do Mogor, Army of the Indian Moguls, &c. Edited and Augmented with The History of Nadir Shah's Invasion By JADUNATH SARKAR, i.e.s., Author of History of Aurangzib, Shivaji and His Times, Studies in Mughal India, &c. Vol. II 1719—1739 Calcutta, M. C. SARKAR & SONS, 1922. Published by C. Sarkar o/ M. C. Sarkar & Sons 90 /2A, Harrison Road, Calcutta. Copyright of Introductory Memoir and Chapters XI—XIII reserved by Jadunath Sarkar and of the rest of the book by Mrs. Margaret L. Seymour, 195, Goldhurst Terrace, London. Printer : S. C. MAZUMDAR SRI GOURANGA PRESS 71/1, Mirzapur Street, Calcutta. 1189/21. CONTENTS Chapter VI. Muhammad Shah : Tutelage under the Sayyids ... 1—101 Roshan Akhtar enthroned as Md. Shah, 1 —peace made with Jai Singh, 4—campaign against Bundi, 5—Chabela Ram revolts, 6—dies, 8—Girdhar Bahadur rebels at Allahabad, 8—fights Haidar Quli, 11 —submits, 15—Nizam sent to Malwa, 17—Sayyid brothers send Dilawar Ali against him, 19— Nizam occupies Asirgarh and Burhanpur, 23—battle with Dilawar Ali at Pandhar, 28—another account of the battle, 32—Emperor's letter to Nizam, 35—plots of Sayyids against Md. Amin Khan, 37—Alim Ali marches against Nizam, 40—his preparations, 43—Nizam's replies to Court, 45—Alim Ali defeated at Balapur, 47—Emperor taken towards Dakhin, 53—plot of Md. Amin against Sayyid Husain Ali, 55—Husain Ali murdered by Haidar Beg, 60—his camp plundered, 61 —his men attack Emperor's tents, 63—Emperor's return towards Agra, 68—letters between Md. -

S. No. Case ID Name Age Gender Address Sample Collection Date

Sample S. No. Case ID Name Age Gender Address Result Date Status District Block Collection Date 1 PIL006482 Azmi 32 female 2020-03-24 2020-03-24 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT H.N.181 Vill-Shahgarh tahsil 2 PIL006617 Balvinder Kaur 58 female 2020-02-04 2020-02-06 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT Kalinagar 3 PIL006621 Balvinder Singh 45 male Haidarpur Amariya 2020-03-19 2020-03-21 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 4 PIL006709 Bhairo Nath 60 male 2020-03-29 2020-03-30 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 5 PIL007046 Chandra Pal 21 male 2020-03-30 2020-03-31 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 6 PIL008157 Dr. Mustak Ahmad 38 male 2020-03-25 2020-03-25 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 7 PIL0011730 Mahboob Hasan 33 male 33 Chidiyadah, Neoria 2020-03-07 2020-03-08 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 8 PIL0013307 Mohd. Aafaq 55 male 2020-03-26 2020-03-27 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 9 PIL0013311 Mohd. Akram 52 male 2020-03-26 2020-03-27 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 10 PIL0014401 Nitin Kapoor 34 male 2020-03-21 2020-03-22 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 11 PIL0017400 Rubeena 26 female 2020-03-24 2020-03-24 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 12 PIL0017401 Rubina Parveen 46 female 2020-03-26 2020-03-27 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 13 PIL0018711 Shabeena Parveen 42 female 2020-03-26 2020-03-27 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 14 PIL0021387 Usman 71 male 2020-03-24 2020-03-24 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 15 PIL0088704 Neha D/ indra pal 19 female tarkothi 2020-04-02 2020-04-03 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT Puranpur 16 PIL0090571 Mohd.Sahib 15 male 2020-04-04 2020-04-06 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT Other 17 PIL0090572 RoshanLal 28 male नो डेटा 2020-04-04 2020-04-06 -

Trendy Travel Trade with Food & Shop

Trendy Travel Trade with Food & Shop Volume VII • Issue II • March 2020 • Pages 52 • Rs.100/- Address: Good Wood Estate, Lower Bharari Road, Bharari Road, Shankli, Longwood, Shimla, Himachal Pradesh 171001 Phone:0177 265 9012 Hola Mohalla, Anandpur Sahib 8 March to 10 March 2020 For More Information Please Contact Tourist information center, Near Gurudwara Takhat Sri Keshgarh sahib, Guru Teg Bahadur museum. Sri Anandpur sahib : Mobile -9779167832, Email - [email protected] PUBLISHER'S NOTE Trendy Travel Trade with Food & Shop Volume VII • Issue II • March 2020 • Pages 52 • Rs.100/- Editor & Publisher : Vedika Sharma Director: Babita Sharma Senior Editor : Tarsh Sharma Reporter : Parul Malhotra Consulting Editor : Pradeep Kapur Consulting Editor(West) : S K Mishra Consultant Art Director : Anita Mudgal Dear Reader, and the aging process. Why not do Graphic Designer : Sangeeta Arya yourself a big favor? Make yourself a priority and take some time off. Consulting Photographer : Ganesh Kapri As we all know vacation time is The best family vacations become around the corner, by keeping this the stuff of legend, inspiring the Manager Administration : Gaurav Kumar in mind T3FS covered a story on stories you and your relatives repeat Family Vacation where we highlighted and reminisce over for years. As far as Manager Circulation : Himanshu Mudgal the “roads less travelled of various memories go, we tend to remember the OUR TEAM OUR destinations”. Family vacations are good things; the time spent together E-mail : [email protected], [email protected] as important as our sleep, so don’t as a family, the new things that were let opportunities to take a family discovered, the new friends we made, Website : www.fabianmedia.net vacation slip away. -

Afghans and Shaikhzadas in the Nobility of Shah Jahan

AFGHANS AND SHAIKHZADAS IN THE NOBILITY OF SHAH JAHAN ABSTRACT '% THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF BoCtOr of $I|tlQ£!09l|P IN HISTORY BY REYAZ AHMAD KHAN Under the Supervision of Dr. AFZAL HUSAIN (READER) CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTiVIENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2000 ABSTRACT "AFGHANS AND SHAIKHZADAS IN THE NOBILITY OF SHAH JAHAN" U£e stuffy of !^^q£af ito6ifiiu £a(f aUracietf i£e aiiention of sc£o/ars of atetf/eoaf S7n<fian £isloru antfa aumoer ofooois ana researc£papers £aoe aureaau Seen puolisoeff. JiowLeoer, auaosl all l£ese slutfies are aeoo/ea lo present l£e role of various racial groups present in t£e nooifitu as a wnofe. S>n recent uears attempts £aoe also oeen maoe to stutfa in tfetail t£e role of important racial yroups indepentfentfu. U£e two prominent racial groups Grants antf Uuranis £aoe Been stutfieff t£oroug£Ju so also t£e Uia/puts out t£e ot£er ta>o local elements C9fq£ans ana dntfian JKas/ims £ave not receioeJ <fue atte.ition. 3n t£e present morJl ate £aoe attempted to prooiife a tfetaife<f a€Xount of t£e position of C^f£yans antf Sfotfian 9lCusfims in t£e noSifity of S£a£ ^a£an. Jfoweoer, it is important to note t£at no suc£ study is aoaifaofe for t£e reiqns of OSaoar, Jfantayun^ ^£oar and ^a£aayir afso. \j£erefore in our introduction we £ad discussedt£ouq£ orieffu about t£eir position duriny earfier period. -

List of Candidates (Provisionally Eligiblenot Eligible) for Research

Central University of Rajasthan Ph.D. Admissions 2021 List of Candidates (Provisionally Eligible/Not Eligible) for Research Aptitude Test, Presentation and Interview Ph.D. in Atmospheric Sciences Provisionally ID No. Student_Name Eligible Remarks (YES / NO) 116 SUBHASH YADAV YES 1227 ANIRUDH SHARMA YES 1345 ROHITASH YADAV YES 219 RITU BHARGAVA RAI YES Subject to submission of application through proper channel 363 SURINA ROUTRAY YES 396 SHANTANU SINHA YES 404 SHRAVANI BANERJEE YES 915 RAJNI CHOUDHARY YES 956 SONIYA YADAV YES 425 JYOTI PATHAK YES 85 SURUCHI YES 1404 BARKHA KUMAWAT NO No proof of qualifying any National Level Examination 988 ANJANA YADAV NO No proof of National Level Examination NOTE: Grievances, if any, w.r.t. above list may be submitted on [email protected] on or before 11th August 2021. The above list is only to appear for Research Aptitude Test, Presentation and Interview and it does not give any claim of final Admission to Ph.D. programme. Page No. 1 of 31 Central University of Rajasthan Ph.D. Admissions 2021 List of Candidates (Provisionally Eligible/Not Eligible) for Research Aptitude Test, Presentation and Interview Ph.D. in Biochemistry Provisionally ID No. Student_Name Eligible Remarks (YES / NO) 1000 SIMRAN BANSAL YES 1032 RAJNI YES 1047 AKASH CHOUDHARY YES 1048 AKASH CHOUDHARY YES 1050 ADITI SHARMA YES 1065 NAVEEN SONI YES 1168 NIDHI KUMARI YES 1185 ANISHA YES 1206 ABHISHEK RAO YES 1212 RASHMI YES 1228 NEELAM KUMARI YES 1241 ANUKRATI ARYA YES 1319 -

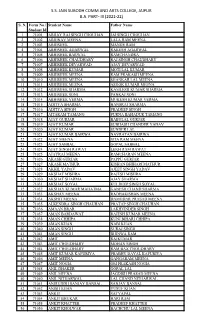

Ss Jain Subodh Comm and Arts College, Jaipur Ba Part

S.S. JAIN SUBODH COMM AND ARTS COLLEGE, JAIPUR B.A. PART- III (2021-22) S. N. Form No./ Student Name Father Name Student Id 1 71001 ABHAY RAJ SINGH CHOUHAN JAI SINGH CHOUHAN 2 71002 ABHINAV MEENA LALA RAM MEENA 3 71003 ABHISHEK MANGE RAM 4 71004 ABHISHEK AGARWAL RAKESH AGARWAL 5 71005 ABHISHEK BARWAL RAMCHANDRA 6 71006 ABHISHEK CHAUDHARY RAJ SINGH CHAUDHARY 7 71007 ABHISHEK DEVARWAD AJAY DEVARWAD 8 71008 ABHISHEK KUMAR MOTI LAL KUMAR 9 71009 ABHISHEK MEENA RAM PRAKASH MEENA 10 71010 ABHISHEK MEENA SHANKAR LAL MEENA 11 71011 ABHISHEK MEENA ASHOK KUMAR MEENA 12 71012 ABHISHEK SHARMA KAMLESH KUMAR SHARMA 13 71013 ABHISHEK SONI PANKAJ SONI 14 71014 ABHISHEK VERMA MUKESH KUMAR VERMA 15 71015 ADITYA SHARMA HANSRAJ SHARMA 16 71016 ADITYA SINGH PRADEEP SINGH 17 71017 AITARAM TAMANG PURNA BAHADUR TAMANG 18 71018 AJAY GURJAR BABULAL GURJAR 19 71019 AJAY KUMAR SUBHASH CHANDER YADAV 20 71020 AJAY KUMAR SUNDER LAL 21 71021 AJAY KUMAR BAIRWA NAVRATAN BAIRWA 22 71022 AJAY MEENA SITA RAM MEENA 23 71023 AJAY SABBAL GOPAL SABBAL 24 71024 AJAY SINGH RAWAT LEKH RAM RAWAT 25 71025 AJAYRAJ MEENA RAMCHARAN MEENA 26 71026 AKASH GURJAR PAPPU GURJAR 27 71027 AKASH MATHUR KISHAN BHIHARI MATHUR 28 71028 AKHIL YADAV AJEET SINGH YADAV 29 71029 AKSHAT MISHRA RAJESH MISHRA 30 71030 AKSHAT SHARMA AJAY SHARMA 31 71031 AKSHAT SOYAL KULDEEP SINGH SOYAL 32 71032 AKSHAY KUMAR MAHATMA GANESH CHAND SHARMA 33 71033 AKSHAY MEENA RADHAKISHAN MEENA 34 71034 AKSHIT MEENA DAMODAR PRASAD MEENA 35 71035 ALKENDRA SINGH CHAUHAN PRATAP SINGH CHAUHAN 36 71036 AMAAN BRAR LAKHVINDER SINGH -

Outlook Traveller Sukoon Houseboat, Ode to Autumn

REGULARS36 EXPLORE EXPLORE 36KASHMIR KASHMIR KASHMIR KASHMIR *** *** *** Dishes to Edenic Out of Town die for Charm Pahalgam and Tabak maaz, The formal Mughal Gulmarg are great harissa, rogan josh gardens are a hit day trips ODE TO We adore Kashmir in spring, summer and winter, but could autumn be its loveliest season? Text and photographs by ↖ Chinar leaves line the ground, Autumn AMIT DIXIT Nishat Bagh 36 DECEMBER 2020 OUTLOOK TRAVELLER 37 ride across the Dal Lake from The pheran may be the Ghat 19A. There were organic quintessential Kashmiri garment of cotton masks, a temperature gun choice but, according to some and copious quantities of sanitiser. sources, it was introduced in EXPLORE EXPLORE Otherwise, I was grateful to note, it was Kashmir by Akbar in the 16th pretty much business as usual, down to century. The traditional pheran SAW MY FIRST FADED CHINAR LEAVES extended to the feet; the the beaming smiles. My friend Altaf WITHOUT WARNING, modern version typically ends I Chapri has elevated the houseboat below the knees. Summer although it wasn’t unexpected, heading out experience with a sunkissed upper ones are lighter and the of Srinagar’s Sheikh ul-Alam Airport, gazing deck—great for meals and yoga lessons version women wear tends to up absentmindedly from the shiny world when the weather is nice—full service, be embroidered. KASHMIR KASHMIR of my smartphone. It was a solitary tree, gourmet meals, stylish décor and, most KASHMIR not even a particularly large one, on Airport important, running hot water. dripping with fat), seekh kabab, methi Road, but striking nevertheless, an amuse- Altaf is a man with a big heart. -

Shivaji the Great

SHIVAJI THE GREAT BY BAL KRISHNA, M. A., PH. D., Fellow of the Royal Statistical Society. the Royal Economic Society. London, etc. Professor of Economics and Principal, Rajaram College, Kolhapur, India Part IV Shivaji, The Man and His .Work THE ARYA BOOK DEPOT, Kolhapur COPYRIGHT 1940 the Author Published by The Anther A Note on the Author Dr. Balkrisbna came of a Ksbatriya family of Multan, in the Punjab* Born in 1882, be spent bis boyhood in struggles against mediocrity. For after completing bis primary education he was first apprenticed to a jewel-threader and then to a tailor. It appeared as if he would settle down as a tailor when by a fortunate turn of events he found himself in a Middle Vernacular School. He gave the first sign of talents by standing first in the Vernacular Final ^Examination. Then he joined the Multan High School and passed en to the D. A. V. College, Lahore, from where he took his B. A* degree. Then be joined the Government College, Lahore, and passed bis M. A. with high distinction. During the last part of bis College career, be came under the influence of some great Indian political leaders, especially of Lala Lajpatrai, Sardar Ajitsingh and the Honourable Gopal Krishna Gokhale, and in 1908-9 took an active part in politics. But soon after he was drawn more powerfully to the Arya Samaj. His high place in the M. A. examination would have helped him to a promising career under the Government, but he chose differently. He joined Lala Munshiram ( later Swami Shraddha- Btnd ) *s a worker in the Guruk.ul, Kangri. -

O)){|P in SOCIOLOGY

SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEPRIVATION OF MUSLIMS IN LOCK AND LAC INDUSTRIES: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF ALIGARH AND HYDERABAD ABSTRACT THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF IBoctor of $i)tlos;o)){|p IN SOCIOLOGY BY SADAF NASIR UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF PROF. ARDUL MATIN DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY AND ?50CIAL WORK ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2011 ABSTRACT The title of the thesis is 'Socio-Economic Deprivation of MusUms in Lock and Lac Industries: A Comparative Study of AUgarh and Hyderabad'. The focus of the study is to examine dispossession and loss of downtrodden Muslim workers of Aligarh lock industry and Hyderabad lac industry respectively. Deprivation of Muslim workers have been examined in terms of (a) material deprivation, (b) Social deprivation, (c) multiple deprivation viz. low income, poor housing and unemployment. The present study is primarily based on field work carried out during April 2009 to March 2010 in Aligarh (U.P.) and Hyderabad (A.P.). The objectives of this study are to explore the socio-economic deprivation of Muslims in Aligarh Lock Industry (Uttar Pradesh) and Hyderabad Lac Industry (Andhra Pradesh) within the fi-amework of relative deprivation. Important issues in this study are as follows: (1) Selected socio-economic indicators viz., family backgroimd, education, income, housing status, health and hygiene and political dimension of the respondents are to be assessed in Aligarh and Hyderabad. (2) To explore the causes and consequences of socio-economic deprivation of Muslims in the lock and Lac industries. (3) To examine, whether the Muslim children supplement to their family income? (3) To assess how and why the Muslims in lock and lac industry are socially and economically deprived. -

The Rise of Dalit Peasants Kolhi Activism in Lower Sindh

The Rise of Dalit Peasants Kolhi Activism in Lower Sindh (Original Thesis Title) Kolhi-peasant Activism in Naon Dumbālo, Lower Sindh Creating Space for Marginalised through Multiple Channels Ghulam Hussain Mahesar Quaid-i-Azam University Department of Anthropology ii Islamabad - Pakistan Year 2014 Kolhi-Peasant Activism in Naon Dumbālo, Lower Sindh Creating Space for Marginalised through Multiple Channels Ghulam Hussain Thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology, Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad, in partial fulfillment of the degree of ‗Master of Philosophy in Anthropology‘ iii Quaid-i-Azam University Department of Anthropology Islamabad - Pakistan Year 2014 Formal declaration I hereby, declare that I have produced the present work by myself and without any aid other than those mentioned herein. Any ideas taken directly or indirectly from third party sources are indicated as such. This work has not been published or submitted to any other examination board in the same or a similar form. Islamabad, 25 March 2014 Mr. Ghulam Hussain Mahesar iv Final Approval of Thesis Quaid-i-Azam University Department of Anthropology Islamabad - Pakistan This is to certify that we have read the thesis submitted by Mr. Ghulam Hussain. It is our judgment that this thesis is of sufficient standard to warrant its acceptance by Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad for the award of the degree of ―MPhil in Anthropology‖. Committee Supervisor: Dr. Waheed Iqbal Chaudhry External Examiner: Full name of external examiner incl. title Incharge: Dr. Waheed Iqbal Chaudhry v ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This thesis is the product of cumulative effort of many teachers, scholars, and some institutions, that duly deserve to be acknowledged here. -

Module 3 Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb Who Was the Successor of Jahangir

Module 3 Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb Who was the successor of Jahangir? Who was the last most power full ruler in the Mughal dynasty? What was the administrative policy of Aurangzeb? The main causes of Downfall of Mughal Empire. Shah Jahan was the successor of Jahangir and became emperor of Delhi in 1627. He followed the policy of his ancestor and campaigns continued in the Deccan under his supervision. The Afghan noble Khan Jahan Lodi rebelled and was defeated. The campaigns were launched against Ahmadnagar, The Bundelas were defeated and Orchha seized. He also launched campaigns to seize Balkh from the Uzbegs was successful and Qandhar was lost to the Safavids. In 1632Ahmadnagar was finally annexed and the Bijapur forces sued for peace. Shah Jahan commissioned the Taj Mahal. The Taj Mahal marks the apex of the Mughal Empire; it symbolizes stability, power and confidence. The building is a mausoleum built by Shah Jahan for his wife Mumtaz and it has come to symbolize the love between two people. Jahan's selection of white marble and the overall concept and design of the mausoleum give the building great power and majesty. Shah Jahan brought together fresh ideas in the creation of the Taj. Many of the skilled craftsmen involved in the construction were drawn from the empire. Many also came from other parts of the Islamic world - calligraphers from Shiraz, finial makers from Samrkand, and stone and flower cutters from Bukhara. By Jahan's period the capital had moved to the Red Fort in Delhi. Shah Jahan had these lines inscribed there: "If there is Paradise on earth, it is here, it is here." Paradise it may have been, but it was a pricey paradise.