(Un)Privilege Or Flesh Tones, Red Bones, and Sepia Shades of Brown

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eloise Butler Wildflower Garden and Bird Sanctuary

ELOISE BUTLER WILDFLOWER GARDEN AND BIRD SANCTUARY WEEKLY GARDEN HIGHLIGHTS Phenology notes for the week of October 5th – 11th It’s been a relatively warm week here in Minneapolis, with daytime highs ranging from the mid-60s the low 80s. It’s been dry too; scant a drop of rain fell over the past week. The comfortable weather was pristine for viewing the Garden’s fantastic fall foliage. Having achieved peak color, the Garden showed shades of amber, auburn, beige, blond, brick, bronze, brown, buff, burgundy, canary, carob, castor, celadon, cherry, cinnabar, claret, clay, copper, coral, cream, crimson, ecru, filemont, fuchsia, gamboge, garnet, gold, greige, khaki, lavender, lilac, lime, magenta, maroon, mauve, meline, ochre, orange, peach, periwinkle, pewter, pink, plum, primrose, puce, purple, red, rose, roseate, rouge, rubious, ruby, ruddy, rufous, russet, rust, saffron, salmon, scarlet, sepia, tangerine, taup, tawny, terra-cotta, titian, umber, violet, yellow, and xanthic, to name a few. According to the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, the northern two thirds of the state reached peak color earlier in 2020 than it did in both 2019 and 2018, likely due to a relatively cool and dry September. Many garter snakes have been seen slithering through the Garden’s boundless leaf litter. Particularly active this time of year, snakes must carefully prepare for winter. Not only do the serpents need to locate an adequate hibernaculum to pass the winter, but they must also make sure they’ve eaten just the right amount of food. Should they eat too little, they won’t have enough energy to make it through the winter. -

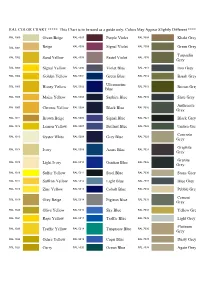

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart Is to Be Used As a Guide Only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** Green Beige Purple V

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart is to be used as a guide only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** RAL 1000 Green Beige RAL 4007 Purple Violet RAL 7008 Khaki Grey RAL 4008 RAL 7009 RAL 1001 Beige Signal Violet Green Grey Tarpaulin RAL 1002 Sand Yellow RAL 4009 Pastel Violet RAL 7010 Grey RAL 1003 Signal Yellow RAL 5000 Violet Blue RAL 7011 Iron Grey RAL 1004 Golden Yellow RAL 5001 Green Blue RAL 7012 Basalt Grey Ultramarine RAL 1005 Honey Yellow RAL 5002 RAL 7013 Brown Grey Blue RAL 1006 Maize Yellow RAL 5003 Saphire Blue RAL 7015 Slate Grey Anthracite RAL 1007 Chrome Yellow RAL 5004 Black Blue RAL 7016 Grey RAL 1011 Brown Beige RAL 5005 Signal Blue RAL 7021 Black Grey RAL 1012 Lemon Yellow RAL 5007 Brillant Blue RAL 7022 Umbra Grey Concrete RAL 1013 Oyster White RAL 5008 Grey Blue RAL 7023 Grey Graphite RAL 1014 Ivory RAL 5009 Azure Blue RAL 7024 Grey Granite RAL 1015 Light Ivory RAL 5010 Gentian Blue RAL 7026 Grey RAL 1016 Sulfer Yellow RAL 5011 Steel Blue RAL 7030 Stone Grey RAL 1017 Saffron Yellow RAL 5012 Light Blue RAL 7031 Blue Grey RAL 1018 Zinc Yellow RAL 5013 Cobolt Blue RAL 7032 Pebble Grey Cement RAL 1019 Grey Beige RAL 5014 Pigieon Blue RAL 7033 Grey RAL 1020 Olive Yellow RAL 5015 Sky Blue RAL 7034 Yellow Grey RAL 1021 Rape Yellow RAL 5017 Traffic Blue RAL 7035 Light Grey Platinum RAL 1023 Traffic Yellow RAL 5018 Turquiose Blue RAL 7036 Grey RAL 1024 Ochre Yellow RAL 5019 Capri Blue RAL 7037 Dusty Grey RAL 1027 Curry RAL 5020 Ocean Blue RAL 7038 Agate Grey RAL 1028 Melon Yellow RAL 5021 Water Blue RAL 7039 Quartz Grey -

E'tac EFX Series Color Wheel TINT

E’TAC EFX series EFX 507 Dark naphtol red EFX 506 Naphtol red color wheel TINT EFX 509 Quina magenta EFX 508 Pyrrole red EFX 507 Dark naphtol red © Eddy & Marissa Wouters http://www.etac-airbrush.com http://www.etac-europe.com EFX 506 Naphtol red EFX 512 Red violet EFX 516 Red ocher EFX 508 Pyrrole red EFX 510 Carbazole violet EFX 505 Azo orange EFX 516 Red ocher EFX 511 Blue violet EFX 517 Brown ocher EFX 505 Azo orange EFX 517 Brown ocher EFX 525 Flesh EFX 525 Flesh EFX 518 Burnt umber EFX 526 Ultramarine blue EFX 518 Burnt umber EFX 519 Culebra gold EFX 504 Golden ocher EFX 523 Sepia smoke HOT colors EFX 503 Arylide yelow EFX 522 Rainforest green EFX 519 EFX 524 Gray Culebra gold EFX 514 Phthalo green EFX 520 Vieques blue EFX 513 Phthalo blue COOL colors EFX 515 Phthalo turquoise EFX 521 Aqua rica EFX 504 EFX 521 Aqua rica Golden ocher EFX 513 Phthalo blue EFX 515 Phthalo turquoise EFX 526 Ultramarine blue EFX 520 Vieques blue EFX 503 Arylide yelow EFX 511 Blue violet EFX 510 Carbazole violet EFX 512 Red violet EFX 514 Phthalo green EFX501 HS Carbon black EFX 522 Rainforest green EFX 509 Quina magenta EFX 524 Gray COOL HOT colors colors EFX502 OT Plasma white EFX 523 Sepia smoke E’TAC EFX series EFX 507 Dark naphtol red EFX 506 Naphtol red Color wheel TONE EFX 509 Quina magenta EFX 508 Pyrrole red EFX 507 Dark naphtol red © Eddy & Marissa Wouters http://www.etac-airbrush.com http://www.etac-europe.com EFX 506 Naphtol red EFX 512 Red violet EFX 516 Red ocher EFX 508 Pyrrole red EFX 510 Carbazole violet EFX 505 Azo orange EFX 516 Red -

Brochure Old Holland Classic Oil Colours Drying Time & Transparency

Old Holland Classic Oil Colours Drying time & Transparency Transparency: * = Transparent **** = Opaque Drying time: F = Fast, M = Medium, S = Slow Oil content: H = High, M = Medium, L = Low, VL = Very Low Colour name Colour index Pigment classification Trans- light- Drying Oil parency fastness time content A1 Titanium white PW6 Titanium dioxide **** 7/8 m l A2 Zinc white PW4 Zinc oxide *** 7/8 m l 3 Lead white PW1 Basic lead carbonate **** 7/8 f vl 4 Flake white no.1 PW1-PW4 Basic lead carbonate zinc oxide **** 7/8 m vl A5 Mixed white no.2 PW6-PW4 Titanium dioxide- zinc oxide **** 7/8 m l A6 Old Holland yellow PW4-PW6- Zinc oxide- Titanium dioxide- Natural ochre **** 7/8 m l light PY43 B8 Old Holland yellow PW4-PW6-PY- Zinc oxide-titanium dioxide-mono.azo-Natural ochre **** 7/8 m l deep 74-PY43 B7 Old Holland yellow PW4-PW6- Zinc oxide-titanium dioxide-monoazo-Natural ochre *** 7/8 m l medium PY74-PY43 B103 Brilliant yellow PW4-PW6- Zinc oxide- Titanium dioxide- Disazo- Diketo pyrollo *** 7/8 m l light PY83-PO73 pyrrole B106 Brilliant yellow PW4-PW6- Zinc oxide- Titanium dioxide- Nickel titanate- Diketo- **** 7/8 m l PY53-PO73 Pyrrolo- Pyrolle B109 Brilliant yellow- PW4-PW6- Zinc white- Titanium dioxide- Nickel titanate- Diketo- **** 7/8 m l reddish PY53-PO73 Pyrrolo- Pyrolle B112 Napels yellow PW4-PW6- Zinc oxide- Titanium dioxide- Nickel titanate- Disazo **** 7/8 m l reddish extra PY53-PO43 B115 Flesh tint PW4-PW6- Zinc oxide- Titanium dioxide- Zinc iron oxide- *** 7/8 m l PY119-PR2 Condensed azo B118 Indian yellow- PY95-PY129 Azo condensation- -

ALTERNATE COLORS the Color Depicted Here Are Available for Secondary Fulfilllment (2-3 Business Days)

100% PURE POLYURE A COLOR SYSTEM KANSAS CITY, USA 800.321.0906 ALTERNATE COLORS The color depicted here are available for secondary fulfilllment (2-3 business days). For additional color choices with shorter fulfillment times, see the Quick Ship Color Chart. VF 1222 The color samples on this chart are for representation of Mocha Tan color only. Colors will vary depending on viewing media. VF 1125¤ Cured color samples are available from Terra Cotta VersaFlex at no charge upon request.* VF 1302 Chestnut VF 1089¤ Very Lt Light Grey VF 1304 Sumatra Brown VF 1228¤ Ostrich Feather VF 1350 Mocha Brown VF 1357¤ Lime Rickey VF 1301 Leather Brown VF 1237¤ Safety Yellow VF 1239 Roman Coffee VF 1360¤ Safety Red (Light) VF 1276 Kaffee VF 1275¤ Red VF 1253 Wheat VF 1330¤ Brick Paver VF 1163 Brevity Brown VF 1287¤ Tile Red VF 1252¤ Terra Cotta Brown VF 1071¤ Burnt Sienna VF 1254 Coyote VF 1224 La Cresenta Brown VF 1077¤ Walnut VF 1309 Raw Sienna VF 1399¤ Raw Sienna (Dark) VF 1262¤ ¤ Relic Bronze VF 1311 Saddle Brown VF 1106 Sand VF 1286 Dark Walnut ¤ Colors marked with this symbol will have an upcharge applied for pigmentation. * VersaFlex advises using actual cured samples when choosing color for projects. © 2017 VersaFlex Incorporated QF7.2.1a.3032 Rev 1 Date-03-20-17 Metzger/McGuire Ameripolish Consolideck Scofield VF 1071 Burnt Sienna Burnt Sienna Burnt Sienna, Terra Cotta Faded Terracotta VF 1077 Cobble Brown, Walnut VF 1089 Very Light Light Grey VF 1106 Sand Cardboard Sand VF 1125 Terra Cotta Chestnut VF 1163 Brevity Brown Bavarian Oak Leather VF -

Color Wheel TINT

E’TAC Private Stock PS 106 BS naphtol red PS 105 Naphtol red Color wheel TINT PS 108 Quina magenta PS 107 Pyrrole red PS 106 BS naphtol red © Eddy & Marissa Wouters http://www.etac-airbrush.com http://www.etac-europe.com PS 113 Red ocher PS 105 Naphtol red PS 117 Red shade violet PS 107 Pyrrole red PS 109 Carbazole violet PS 104 Azo orange PS 113 Red ocher PS 114 Brown ocher PS 116 Blue shade violet PS 104 Azo orange PS 114 Brown ocher PS 203 Flesh (opaque) PS 203 Flesh (opaque) PS 115 Burnt umber PS 134 Ultramarine blue PS 115 Burnt umber PS 118 Culebra gold PS 103 Golden ocher PS 122 Sepia smoke HOT colors PS 102 Arylide yelow PS 118 PS 121 Rainforest green Culebra gold PS 123 Portrait gray PS 111 Phthalo green PS 110 Phthalo blue PS 119 Vieques blue COOL colors PS 112 Phthalo turquoise PS 120 Aqua rica PS 103 Golden ocher PS 120 Aqua rica PS 110 Phthalo blue PS 112 Phthalo turquoise PS 134 Ultramarine blue PS 119 Vieques blue PS 102 Arylide yelow PS 116 Blue shade violet PS 109 Carbazole violet PS 117 Red shade violet PS 111 Phthalo green PS 101 Shading Black PS 200 Op. HS Carbon Black PS 121 Rainforest green PS 108 Quina magenta PS 123 Portrait gray COOL HOT colors colors PS 100 Tinting White PS 122 Sepia smoke PS 201 Op. Titanium Plasma White E’TAC Private Stock PS 106 BS naphtol red PS 105 Naphtol red Color wheel TONE PS 108 Quina magenta PS 107 Pyrrole red PS 106 BS naphtol red © Eddy & Marissa Wouters http://www.etac-airbrush.com http://www.etac-europe.com PS 113 Red ocher PS 105 Naphtol red PS 117 Red shade violet PS 107 Pyrrole -

Watercolor Substitution Cheat Sheet * = Lindsay Recommended Color

Watercolor Substitution Cheat Sheet * = Lindsay Recommended color *Phthalo Blue (Strong cool-green leaning-blue) Prussian Blue (also look for that pigment) AKA Pthalo blue GS Cyan Blue or green shade. Cerulean Blue (if it looks dark: Mission Gold) Helio Cerulean **This colors is great for mixing green when Winsor Blue (Winsor & Newton) paired with a cool yellow. Intense Blue (Winsor & Newton/Cotman) Azure (Yarka/White Nights) Turquoise Indigo (deep cool blue grey) Indanthrone Blue Payne's Grey+Prussian Blue *Ultramarine Blue (warm, purple bias red) Colbalt Blue Pthalo blue Red Shade (not my fave substitute) **This color is good for mixing violet with a cool Poland Blue red or gray with burnt sienna. ***This color granulates for textured washes. Cerulean Blue (Less intense cool blue) Manganese Blue Phthalo blue + white Cinerous Blue (Sennelier) *Quinacridone Rose (Cool red with violet Alizarian Crimson undertones) Carmine **This color makes lovely purples and mauve Crimson lake with blues. Rose Madder (weaker than AZ) *Cadmium Red or Cadmium red light Vermilion (Warm red with orange undertones) Scarlet Napthol Red **This color makes beautiful oranges when mixed Bright Red/ Brilliant Red with warm yellows. Pyrrole Red Permanent Rose Magenta *Cadmium Yellow (warm yellow) Gamboge Cadmium yellow medium/Cadmium yellow deep Indian Yellow Permanent yellow deep **This color makes beautiful oranges when mixed with warm reds or peach with cool reds *Hansa Yellow Light (cool yellow) Lemon Yellow (cool yellow) Cadmium yellow light, pale or Cadmium -

Color-Proposal.Pdf

Colors in Snap! -bh proposal, draft, do not distribute Your computer monitor can display millions of colors, but you probably can’t distinguish that many. For example, here’s red 57, green 180, blue 200: And here’s red 57, green 182, blue 200: You might be able to tell them apart if you see them side by side: … but maybe not even then. Color space—the collection of all possible colors—is three-dimensional, but there are many ways to choose the dimensions. RGB (red-green-blue), the one most commonly used, matches the way TVs and displays produce color. Behind every dot on the screen are three tiny lights: a red one, a green one, and a blue one. But if you want to print colors on paper, your printer probably uses a different set of three colors: CMY (cyan-magenta-yellow). You may have seen the abbreviation CMYK, which represents the common technique of adding black ink to the collection. (Mixing cyan, magenta, and yellow in equal amounts is supposed to result in black ink, but typically it comes out a not-very-intense gray instead.) Other systems that try to mimic human perception are HSL (hue-saturation-lightness) and HSV (hue-saturation-value). If you are a color professional—a printer, a web designer, a graphic designer, an artist—then you need to understand all this. It can also be interesting to learn about. For example, there are colors that you can see but your computer display can’t generate. If that intrigues you, look up color theory in Wikipedia. -

Series 29 Durable Powder Coatings

29 TIGER WORLDWIDE NETWORK Series 29 Durable Powder Coatings T H E A M E R I C A S CANADA E U R O P E MEXICO AUSTRIA A S I A U.S.A. BELARUS CHINA BENELUX INDIA BOSNIA & HERZEGOVINA JAPAN BULGARIA MALAYSIA CROATIA TAIWAN CZECH REPUBLIC VIETNAM ESTONIA FRANCE A F R I C A GERMANY EGYPT GREAT BRITAIN SOUTH AFRICA HUNGARY ITALY LATVIA LITHUANIA POLAND QUALICOAT Class I | GSB Standard ROMANIA SERBIA & MONTENEGRO SLOVAKIA SLOVENIA SPAIN SWEDEN TURKEY UKRAINE current address and other information at www.tiger-coatings.com 1555 / 05-18 Fotocredit: Page 1 l. to r.: Verkehrsbüro Kongresshotellerie GmbH, gionnixxx - istockphoto | Page 2/3: xijian - istockphoto | Page 4: Oleh_Slobodeniuk - istockphoto | Page 5: Alija - istockphoto, green coating amriphoto.com - istockphoto | Page 6: Calin-Andrei STAN - istockphoto | Page 7: franckreporter - istockphoto A GREENER FINISH. FOR A BETTER WORLD. a finish by TIGER Coatings GmbH & Co. KG TIGER Drylac® Durable Powder Coatings for Metal Facades & Steel Construction Elegance and quality in perfect harmony The purpose of a facade is multifaceted and is somewhat comparable to that of the human skin. It gives the buil- ding its individual charm, separates the interior from the exterior and protects it against sun, wind and weather. Thus, when it comes to selecting the best-possible coating of the facade, apart from high quality, the design plays a crucial part too. TIGER Drylac® Series 29 for metal facades and steel cons- truction is subject to the strict quality and test regulations of GSB International and QUALICOAT. It stands out with its weather and abrasion resistance and its UV and corrosion stability. -

Uniform Color Descriptions Glossary of Terms

The International Cat Association Uniform Color Descriptions and Glossary of Terms Version D (09/04/20) Preface to By-Laws, Registration Rules, Show Rules, Standing Rules Uniform Color Descriptions and Standards The By-Laws take precedence over ALL other Rules, followed by the Registration Rules, Show Rules, Standing Rules, and Uniform Color Descriptions, in that order. The Registration Rules, Show Rules, Standing Rules, and Uniform Color Descriptions shall take precedence over any individual Breed Standard UNLESS that Standard is MORE restrictive than the general rules applying to ALL breeds, in which case the Standard shall take precedence. TICA Uniform Color Descriptions, Page 2 Version D 09/04/20 Uniform Color Descriptions Table of Contents 71 Categories, Divisions and Colors. ........................................................................ 4 72 Solid Divisions ..................................................................................................... 8 73 Tortoiseshell Divisions. ........................................................................................ 8 74 Tabby Divisions. .................................................................................................. 9 75 Silver and/or Smoke Divisions. .......................................................................... 14 76 Any Color with White Divisions. ......................................................................... 18 Color Definitions ........................................................................................................ -

Daniel Smith Cielab Spreadsheet

DANIEL SMITH Watercolors - CIELab Cool/Warm Rating WARMEST COLORS WARM COLORS COOL COLORS COOLEST COLORS Alizarin Crimson Monte Amiata Natural Sienna Amazonite Genuine Amethyst Genuine Blue Apatite Genuine Alvaro's Caliente Grey Mummy Bauxite Aureolin (Cobalt Yellow) Carbazole Violet Cerulean Blue Anthraquinoid Red Naphthamide Maroon Azo Yellow Cobalt Blue Violet Cerulean Blue Chromium Anthraquinoid Scarlet Naples Yellow Bismuth Vanadate Yellow Cobalt Violet Cobalt Blue Aussie Red Gold New Gamboge Black Tourmaline Genuine Cobalt Violet Deep Cobalt Teal Blue Bloodstone Genuine Nickel Azo Yellow Cadmium Yellow Light Hue French Ultramarine Cobalt Turquoise Bordeaux Olive Green Cascade Green Imperial Purple Jane's Grey Bronzite Genuine Organic Vermilion Chinese White Indanthrone Blue Kyanite Genuine Buff Titanium Perinone Orange Chromium Green Oxide Indigo Lapis Lazuli Genuine Burgundy Red Ochre Permanent Alizarin Crimson Cobalt Green Lavender Lunar Blue Burgundy Yellow Ochre Permanent Brown Cobalt Green Pale Lunar Violet Manganese Blue Hue Burnt Bronzite Genuine Permanent Orange Deep Sap Green Mayan Violet Mayan Blue Genuine Burnt Sienna Permanent Red Diopside Genuine Moonglow Mayan Dark Blue Burnt Sienna Light Permanent Red Deep Fuchsite Genuine Opera Pink Payne's Blue Gray Burnt Tiger's Eye Genuine Permanent Yellow Deep Green Apatite Genuine Permanent Violet Payne's Gray Burnt Umber Perylene Maroon Green Gold Purpurite Genuine Phthalo Blue (Green Shade) Burnt Yellow Ochre Perylene Red Hansa Yellow Light Quinacridone Lilac Phthalo Blue -

Swatch Name HLS RGB HEX Absolute Zero 217° 36% 100% 0 72

Swatch Name HLS RGB HEX Absolute Zero 217° 36% 100% 0 72 186 #0048BA Acid green 65° 43% 76% 176 191 26 #B0BF1A Aero 206° 70% 70% 124 185 232 #7CB9E8 Aero blue 151° 89% 100% 201 255 229 #C9FFE5 African violet 288° 63% 31% 178 132 190 #B284BE Air superiority blue 205° 60% 39% 114 160 193 #72A0C1 Alabaster 46° 90% 27% 237 234 224 #EDEAE0 Alice blue 208° 97% 100% 240 248 255 #F0F8FF Alloy orange 27° 42% 85% 196 98 16 #C46210 Almond 30° 87% 52% 239 222 205 #EFDECD Amaranth 348° 53% 78% 229 43 80 #E52B50 Amaranth (M&P) 328° 40% 57% 159 43 104 #9F2B68 Amaranth pink 338° 78% 75% 241 156 187 #F19CBB Amaranth purple 342° 41% 63% 171 39 79 #AB274F Amaranth red 356° 48% 73% 211 33 45 #D3212D Amazon 147° 35% 35% 59 122 87 #3B7A57 Amber 45° 50% 100% 255 191 0 #FFBF00 Amber (SAE/ECE) 30° 50% 100% 255 126 0 #FF7E00 Amethyst 270° 60% 50% 153 102 204 #9966CC Android green 74° 50% 55% 164 198 57 #A4C639 Antique brass 22° 63% 47% 205 149 117 #CD9575 Antique bronze 52° 26% 55% 102 93 30 #665D1E Antique fuchsia 316° 46% 22% 145 92 131 #915C83 Antique ruby 350° 31% 66% 132 27 45 #841B2D Antique white 34° 91% 78% 250 235 215 #FAEBD7 Ao (English) 120° 25% 100% 0 128 0 #008000 Apple green 74° 36% 100% 141 182 0 #8DB600 Apricot 24° 84% 90% 251 206 177 #FBCEB1 Aqua 180° 50% 100% 0 255 255 #00FFFF Aquamarine 160° 75% 100% 127 255 212 #7FFFD4 Swatch Name HLS RGB HEX Arctic lime 72° 54% 100% 208 255 20 #D0FF14 Army green 69° 23% 44% 75 83 32 #4B5320 Artichoke 76° 53% 13% 143 151 121 #8F9779 Arylide yellow 51° 67% 74% 233 214 107 #E9D66B Ash gray 135° 72% 8% 178 190