Second Work Plan of the European Coordinator Karla Peijs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manual on Border Controls Along the Danube and Its Navigable Tributaries

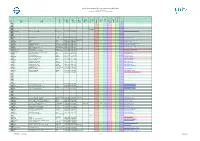

EU Strategy for the Danube Region Priority Area 1a – To improve mobility and multimodality: Inland waterways Practical manual on border controls along the Danube and its navigable tributaries Author(s): Milica Gvozdic (viadonau) Simon Hartl (viadonau) Katja Rosner (viadonau) Version (date): 31.08.2015 1 General information .................................................................................................................. 4 2 How to use this manual? .......................................................................................................... 5 3 Geographic scope .................................................................................................................... 5 4 Hungary ................................................................................................................................... 7 4.1 General information on border controls ................................................................................... 7 4.1.1 Control process ................................................................................................................... 8 4.1.2 Control forms ..................................................................................................................... 10 4.1.3 Additional information ....................................................................................................... 21 4.2 Information on specific border control points ......................................................................... 22 4.2.1 Mohács ............................................................................................................................. -

“Bulgarian State Railways - Cargo Freights” Ltd

Journal of Advanced Management Science Vol. 7, No. 2, June 2019 The Necessity to Improve the Competitive Power of “Bulgarian State Railways - Cargo Freights” Ltd. S Tzvetkova and E Savova University of National and World Economy, Sofia, Bulgaria Email: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract—“Bulgarian State Railways - Cargo Freights” Ltd. replacement services in cargo railway transport can be is the leading association on the Bulgarian market for evaluated as HIGH, which has a negative reflection on carrying out railway cargo freights. In recent years, freight volumes in the sector, with it reaching up 10% in however, the freight volume has decreased and the comparison to other types of transport. The traction- company has reported negative financial indicators. The changes that have occurred in Bulgarian economy, the rolling stock is growing old, which leads to operative market’s liberalization, the impossibility for making problems, increased repair costs and deteriorated quality investments, the obsolete rolling stock, the deteriorating of services, which respectively reduces the competitive quality of transport services and the reduced competitive power. power are among the main reasons for that. The The financial situation of “BSR – Cargo Freights” Ltd. substantiated necessity for increasing the freight volume, is serious. In its short 10-year history, the association has improving the financial indicators and retaining the market registered negative financial indicators which result from share is the main motive for writing this paper. To that end, the external environ ment and from ineffective internal factors from the internal and external environments have activities and processes. The total amount of losses for been analyzed through the implementation of PESTEL, 5 FORCES and SWOT analyses. -

Annex to 3Rd IRG-Rail Market Monitoring Report

IRG-Rail (15) 02a_rev1 Independent Regulators’ Group – Rail IRG–Rail Annexes to the 3rd IRG-Rail Annual Market Monitoring Report March 2015 IRG-Rail Annexes to the Annual Market Monitoring Report Index 1. Country sheets market structure.................................................................................2 2. Common list of definitions and indicators ...............................................................299 3. Graphs and tables not used in the report................................................................322 1 IRG-Rail Annexes to the Annual Market Monitoring Report 1. Country sheets market structure Regulatory Authority: Schienen-Control GmbH Country: Austria Date of legal liberalisation of : Freight railway market: 9 January 1998. Passenger railway market: 9 January 1998. Date of entry of first new entrant into market: Freight: 1 April 2001. Passenger: 14 December 2003. Ownership structure Freight RCA: 100% public Lokomotion: 30% DB Schenker, 70% various institutions with public ownership LTE: 100% public (was 50% private, new partner to be announced May 2015) Cargoserv, Ecco-Rail, RTS: 100% private TXL: 100% public (Trenitalia) Raaberbahn Cargo: 93.8% public SLB, STB, GKB, MBS, WLC: 100% public RPA: 53% private, 47% public (City of Hamburg: 68% HHLA, HHLA: 85% Metrans, Metrans: 80% RPA) Passenger ÖBB PV 100% public WLB, GKB, StLB, MBS, StH, SLB: 100% public CAT: 49.9% ÖBB PV, 50.1% Vienna Airport (public majority) WESTbahn: 74% private, 26% public (SNCF Voyageurs) Main developments Rail freight traffic once again receded slightly in 2013 on the previous year. The new entrants could raise their market share in traffic frequency (tons) from 23.2 to 24.9 percent, and their share in transport performance (net tons per kilometre) rose from 17.6 to 19.3 percent. -

CP Stations in Ruse Multilanguage V2.1-EN

AXECARD’s stations network expands to Bulgaria 29 March 2021, AXEGAZ Trading and Technologies SAS ("ATT") continues expanding the network of LNG and CNG stations accepting the AXECARD . We have recently added two new stations in Bulgaria, both based in Ruse , on the Danube, near the border with Romania. The network of stations that accept the AXECARD, with all information including their status in real time can be browsed via the AXECARD mobile phone application: The LNG station is situated in the heart of the Danube Industrial Zone TEGRA and is the first and only of its kind in Bulgaria. The station is located at the following coordinates 43.9025717792975 N , 26.063466944998567 E . It is easily accessible via Route 21 , heading to the East from the Danube Bridge Roundabout . AXECARD’s stations network expands to Bulgaria 29 March 2021 The other station distributes CNG . It is positioned in Ruse Western Industrial Zone at the following coordinates: 43.82130280144999 N, 25.928356611096156 E The address 74 bul.3ti Mart is swiftly accessible from both East and West lanes of E85 via the exit to Route 5 and bul. 3ti Mart . LNG as a road fuel: economic, competitive and strategic Natural gas is incontestably the fuel of the future for heavy-duty vehicles. The use of Liquid Natural Gas (LNG) growth is particularly strong as it offers the key advantage of a range of up to 1,700 km with a double tank, thus overcoming a major limitation posed by Compressed Natural Gas (CNG) at the same time maintaining a great economic and environmental advantage of natural gas over diesel: • 20% reduction of CO2 emissions, (and up to 90% bio-LNG now available), • 96% reduction fine particles, • 70% reduction of nitrogen dioxides. -

Masterplan for Lng on Rhine-Main-Danube Axis Building a Pioneer Market and Lng Artery for Europe

MASTERPLAN FOR LNG ON RHINE-MAIN-DANUBE AXIS BUILDING A PIONEER MARKET AND LNG ARTERY FOR EUROPE Manfred Seitz LNG Masterplan: Status April 2015 Project Coordinator 2 RATIONALE FOR LNG IN IWT • Environmental drivers • LNG as fuel reduces air emissions (-10-20% CO2, -80-90% NOx, almost zero PM & SOx) • Further CO2 reduction possible by “blending” (balance) with BIO-LNG • Economic drivers • Price gap Gasoil - LNG and estimated price reduction for LNG due to massive production increase; favourable payback time of investment; significant reduction in fuel consumption; fuel cost savings result into higher profitability/lower transport costs • LNG as cargo will increase transport volumes and will offer energy cost savings to many industries along the Rhine-Main-Danube axis; reduces oil dependency and supports diversification of energy mix • Regulations • EU Directive on Deployment of Alternative Fuels Infrastructure (approved April 2014) demands deployment of LNG fuelling infrastructure (in a sufficient number of maritime ports till 2025, inland ports till 2025, core road network till 2025 & common technical standards for CNG and LNG refuelling points by 2015 • Future air emission regulation: “LNG most effective measure to reach Stage IV for medium and large inland vessels” (NAIADES 2/Panteia-NEA report) • ECA/SECA regulation which fosters built-up of LNG infrastructure in NW-Europe and development of Small Scale LNG Supply Chains LNG Masterplan: Status April 2015 3 SURPLUS IN LNG SUPPLY LNG Masterplan: Status April 2015 4 400 LNG-FUELED VESSELS IN OPERATION THROUGHOUT EUROPE BY 2020 LNG fuelled vessels worldwide & per region per shiptype [#] . DNV expects 1.000 vessels to be running on LNG by 2020 of which 400 will operate in Europe 5 LNG EXPECTED TO ACCOUNT FOR CA. -

DIOMIS Bulgaria

DIOMIS Evolution of intermodal rail/road traffic in Central and Eastern Sandra Géhénot International Union of Railways Tel: +33 (0) 1 44 49 20 84 16, rue Jean Rey - F 75015 Paris Fax: +33 (0) 1 44 49 20 79 Tel: +33 (0) 1 44 49 20 20 European Countries by 2020 www.uic.org/diomis Fax: +33 (0) 1 44 49 20 29 e-mail: [email protected] www.uic.org BULGARIA Developing Infrastructure & Operating Models for Intermodal Shift © ETF publication - 2009 December 2009 ISBN 978-2-7461-1737-2 Warning No part of this publication may be copied, reproduced or distributed by any means whatsoever, including electronic, except for private and individual use, without the express permission of the International Union of Railways (UIC). The same applies for translation, adaptation or transformation, arrangement or reproduction by any method or procedure whatsoever. The sole exceptions - noting the author’s name and the source - are “analyses and brief quotations justifi ed by the critical, argumentative, educational, scientifi c or informative nature of the publication into which they are incorporated”. (Articles L 122-4 and L122-5 of the French Intellectual Property Code). © Copyright - Paris, 2009 CONTENTS 1. Socio-economic information on Bulgaria .................................1 1.1 - Population .........................................................................................................2 1.2 - Economy ...........................................................................................................3 1.3 - Freight traffi c .....................................................................................................6 -

Profilul Investitional Al Euroregiunii Ruse-Giurgiu

DAS INVESTITIONSPROFIL DER EUROREGION RUSE-GIURGIU 2012 1. Vorwort Liebe Leser, Ich habe die Ehre, in dem Namen von über 200.000 Einwohnern der Euroregion Ruse-Giurgiu die echte und warme Einladung zu senden, um zusammen mit uns die Ressourcen und die Schönheit dieses Gebiets, das seit über 2000 Jahren ein Gastgeber für zwei Völker – Rumänisch und Bulgarisch ist, zu genießen. Ob in der Vergangenheit die Donau diejenige war, die beiden Gemeinden getrennt hat, ist in der Gegenwart der Fluss derjenige, der uns verbindet. Dieser macht uns mit Zuversicht in der Richtung einer europäischen Zukunft anzuschauen. Außerdem, wir sind jetzt bedingt wie eine große Familie zu denken und zu handeln. Die Euroregion Ruse – Giurgiu ist derzeit die größte städtische Gemeinde an der rumänischen – bulgarischen Grenze und der wichtigste Verkehrsknotenpunkt zwischen den beiden Staaten, seit 2007 Mitglieder mit vollen Kräften der Europäischen Union, und weiter an den Märkten des Mittelmeerraums und Kleinasien. Auf anderer Seite, hat die Euroregion eine einzigartige strategische Position in Süd-Ost Europa, denn sie befindet sich an der Kreuzung der paneuropäischen Korridoren, die Nord – und Westeuropa und Asien verbindet. Man behauptet hier, dass Giurgiu Hafen der näheste Hafen von Rumäniens Hauptstadt – Bukarest – ist, die ein Markt von rund 3 Milionen Verbraucher, befindet nur 65 Kilometer weit, ist. Die beiden städtischen Gemeinden aus der Euroregion – Ruse und Giurgiu – polasieren zwei überwiegend ländliche Gemeinden, mit über 300.000 Hektar von fruchtbarem Land, ideal für den ökologischen Landbau, Ressourcen des Landes (Öl, Gas, Baustoffe), aber auch den Gang von Donau, wo über 10.000 Hektar von großen Parks und Naturschützgebieten, mit einzigartigen Landschaften auf europäischem Niveau, sich finden. -

List of Numeric Codes for Railway Companies

List of numeric codes for railway companies (RICS Code) contact : [email protected] reference : http://www.uic.org/spip.php?article311 code short name full name country request date allocation date modified date beginof validity of end validity recent Freight Passenger Infra- structure Holding Integrated Other url 0001 0002 0003 0004 0005 01/02/2011 0006 StL Holland Stena Line Holland BV Netherlands 01/07/2004 01/07/2004 x http://www.stenaline.nl/ferry/ 0007 0008 0009 0010 VR VR-Yhtymä Oy Finland 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 x http://www.vr.fi/fi/ 0011 0012 TF Transfesa Spain 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 10/09/2013 x http://www.transfesa.com/ 0013 OSJD OSJD Poland 12/07/2000 12/07/2000 x http://osjd.org/ 0014 CWL Compagnie des Wagons-Lits France 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 x http://www.cwl-services.com/ 0015 RMF Rail Manche Finance United Kingdom 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 x http://www.rmf.co.uk/ 0016 RD RAILDATA Switzerland 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 x http://www.raildata.coop/ 0017 ENS European Night Services Ltd United Kingdom 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 x 0018 THI Factory THI Factory SA Belgium 06/05/2005 06/05/2005 01/12/2014 x http://www.thalys.com/ 0019 Eurostar I Eurostar International Limited United Kingdom 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 x http://www.eurostar.com/ 0020 OAO RZD Joint Stock Company 'Russian Railways' Russia 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 x http://rzd.ru/ 0021 BC Belarusian Railways Belarus 11/09/2003 24/11/2004 x http://www.rw.by/ 0022 UZ Ukrainski Zaliznytsi Ukraine 15/01/2004 15/01/2004 x http://uz.gov.ua/ 0023 CFM Calea Ferată din Moldova Moldova 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 -

Bulgaria Npf.En.Pdf

REPUBLIC OF BULGARIA CABINET Copy DECISION No 3 2 3 of 11 May 2018 AMENDING THE NATIONAL POLICY FRAMEWORK FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE MARKET AS REGARDS ALTERNATIVE FUELS IN THE TRANSPORT SECTOR AND THE DEPLOYMENT OF THE RELEVANT INFRASTRUCTURE T H E CABINET HAS DECIDED AS FOLLOWS: 1. To amend the national policy framework for the development of the market as regards alternative fuels in the transport sector and the deployment of the relevant infrastructure, as set out in the Annex. 2. To designate the following central government bodies to take the requisite actions to transpose specific provisions of Directive 2014/14/EC in accordance with the national policy framework for the development of the market as regards alternative fuels in the transport sector and the deployment of the relevant infrastructure, as follows: (a) Ministry of Energy: The Ministry of Energy shall draw up a draft Act amending the Energy Act, transposing the provisions of Article 4, paragraphs (7), (8), first sentence, (9), (11) and (12) of Directive 2014/14/EC on the deployment of alternative fuels infrastructure. (b) Energy and Water Regulatory Commission: The Energy and Water Regulatory Commission shall take action so as to ensure that recharging point operators are able to provide electric vehicle recharging services to customers on a contractual basis, including in the name and on behalf of other service providers. In addition, the Commission shall ensure that all recharging points accessible to the public also provide for electric vehicle users to recharge on an ad hoc basis without entering into a contract with the electricity supplier or operator concerned (Article 4(8), second sentence, and (9) of Directive 2014/94/EC); (c) Consumer Protection Commission: The Consumer Protection Commission shall take action to ensure that prices charged by the operators of recharging points accessible to the public are reasonable, easily and clearly comparable, transparent and non-discriminatory (Article 4(10) of Directive 2014/94/EC). -

Transportation, Smuggling and Organized Crime 91

TRANSPORTATION, SMUGGLING, AND ORGANIZED CRIME CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF DEMOCRACY CSD REPORTS: 1. Bulgaria’s Participation in EU Structural Funds, Sofia, 1999. ISBN 954-477-050-8 2. Social Policy Aspects of Bulgaria’s EU Accession, Sofia, 1999. ISBN 954-477-053-4 3. Preparing for EU Accession Negotiations, Sofia, 1999. ISBN 954-477-055-7 4. The Role of Political Parties in Accession to the EU, Sofia, 1999. ISBN 954-477-055-0 5. Bulgaria’s Capital Markets in the Context of EU Accession: A Status Report, Sofia, 1999. ISBN 954-477-059-3 6. Corruption and Trafficking: Monitoring and Prevention, Sofia, 2000. ISBN 954-477-078-X 7. Establishing Corporate Governance in an Emerging Market: Bulgaria, Sofia, 2000. ISBN 954-477-084-4 9. Corruption and Illegal Trafficking: Monitoring and Prevention, Second, revised and amended edition, Sofia, 2000. ISBN 954-477-087-9 10. Smuggling in Southeast Europe, Sofia, 2002. ISBN 954-477-099-2 11. Corruption, Trafficking and Institutional Reform, Sofia, 2002. ISBN 954-477-101-8 12. The Drug Market in Bulgaria, Sofia, 2003. ISBN 954-477-111-5 13. Partners in Crime: The Risks of Symbiosis between the Security Sector and Organized Crime in Southeast Europe, Sofia, 2004. ISBN 954-477-115-8 14. Weapons under Scrutiny: Implementing Arms Export Controls and Combating Small Arms Proliferation in Bulgaria, Sofia, 2004. ISBN 954-477-117-470 15. Transportation, Smuggling, and Organized Crime, Sofia, 2004. ISBN 954-477-119-0 Editorial Board: Ognian Shentov Boyko Todorov Alexander Stoyanov ISBN 954-477-119-0 ©2004 Center for the Study of Democracy All rights reserved. -

The Sustainable Freight Railway: Designing the Freight Vehicle – Track System for Higher Delivered Tonnage with Improved Availability at Reduced Cost SUSTRAIL

The sustainable freight railway: Designing the freight vehicle – track system for higher delivered tonnage with improved availability at reduced cost SUSTRAIL Grant Agreement n°: 265740 FP7 - THEME [SST.2010.5.2-2.] Project Start Date: 2011-06-01 Duration: 48 months [DELIVERABLE 2.2] [FUTURE LOGISTICS REQUIREMENTS] Due date of deliverable: 29/02/2012 Actual submission date: 29/03/2012 Work Package Number: [WP 2] Dissemination Level: [CO] Status: [Draft] Leader of this deliverable: [Tilman Platz, MARLO] Prepared by: [Tilman Platz, MARLO][Roland Frindik, MARLO] [Roberto Loiero, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid] [Juan Andrés Brunel Vázquez, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid] [Dewan Islam, Newcastle University] [John Nellthorp, University of Leeds] Verified by: [Andrew Jablonski, Network Rail] Dissemination Level PU Public PP Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission Services) RE Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission Services) CO Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the Commission Services) [CO–v2] Page 2 of 73 Document History Version Date Author/s Description [v1] [2011-09-12] [Tilman Platz] [Working document to specify the input of the partners] [v2a] [2011-12-15] [Tilman Platz, Roberto Loiero] [First drafting on Bulgarian and UK routes, introduction to Chapter 2] [v2b] [2012-01-17] [Tilman Platz, revision by John [Logistics trends, future Nellthorp] freight flows in UK and Bulgaria, first review] [v2c] [2012-01-18] [Tilman Platz, Dewan Islam, [First -

Importance of Lng in Turkish Natural Gas Supply Security

KADİR HAS UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES ENGINEERING DISCIPLINE AREA IMPORTANCE OF LNG IN TURKISH NATURAL GAS SUPPLY SECURITY MEHMET BATUHAN ALKAN ADVISOR: PROF.DR. VOLKAN Ş. EDİGER COADVISOR: ASSOC. PROF.DR. GÖKHAN KİRKİL MASTER’S THESIS ISTANBUL, MARCH, 2019 IMPORTANCE OF LNG IN TURKISH NATURAL GAS SUPPLY SECURITY MEHMET BATUHAN ALKAN ADVISOR: PROF.DR. VOLKAN Ş. EDİGER COADVISOR: ASSOC. PROF.DR. GÖKHAN KİRKİL MASTER’S THESIS Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of Kadir Has University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s in the Discipline Area of Engineering under the Program of Energy and Sustainable Development ISTANBUL, MARCH, 2019 ACCEPTANCE AND APPROVAL This work entitled IMPORTANCE OF LNG IN TURKISH NATURAL GAS SUPPLY SECURITY prepared by MEHMET BATUHAN ALKAN has been judged to be successful at the defense exam held on 25/03/2019 and accepted by our jury as MASTER’S THESIS. Prof.Dr. Volkan Ş. Ediger (Advisor) Kadir Has University Hakİyi Assoc.Prof.Dr. Gökhan Kirkil (Coadvisor) Kadir Has University Asst.Prof.Dr. Filiz Katman Istanbul Aydın University a— ( 5 Asst.Prof.Dr. Emre Celebi Kadir Has University aAAAA I certify that the above signatures belong to the faculty members nam abo A Prof. Dr. Sinem AKGUL\ACIKMESE , Dean School of Graduate Studies Date of Approval 25.03.2019 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to express my gratitude to my supervisor Prof. Volkan Ş. Ediger who is accepted me as a MA student at the Energy and Sustainable Development Master Program of Kadir Has University. I would also like to thank my co-supervisor, Assoc.