Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair (RTC) with Biceps Tenodesis Rehab

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rehabilitation Guidelines for Type I and Type II Rotator Cuff Repair and Isolated Subscapularis Repair

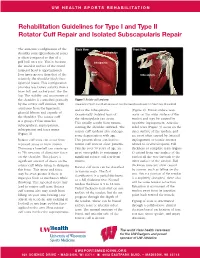

UW HEALTH SPORTS REHABILITATION Rehabilitation Guidelines for Type I and Type II Rotator Cuff Repair and Isolated Subscapularis Repair The anatomic configuration of the Back View Front View shoulder joint (glenohumeral joint) Supraspinatus is often compared to that of a golf ball on a tee. This is because Infraspinatus the articular surface of the round humeral head is approximately Teres four times greater than that of the Minor Subscapularis relatively flat shoulder blade face (glenoid fossa). This configuration provides less boney stability than a truer ball and socket joint, like the hip. The stability and movement of the shoulder is controlled primarily Figure 1 Rotator cuff anatomy by the rotator cuff muscles, with Image property of Primal Pictures, Ltd., primalpictures.com. Use of this image without authorization from Primal Pictures, Ltd. is prohibited. assistance from the ligaments, and/or the infraspinatus. (Figure 2). Bursal surface tears glenoid labrum and capsule of Occasionally isolated tears of occur on the outer surface of the the shoulder. The rotator cuff the subscapularis can occur. tendon and may be caused by is a group of four muscles: This usually results from trauma repetitive impingement. Articular subscapularis, supraspinatus, rotating the shoulder outward. The sided tears (Figure 3) occur on the infraspinatus and teres minor rotator cuff tendons also undergo inner surface of the tendon, and (Figure 1). some degeneration with age. are most often caused by internal Rotator cuff tears can occur from This process alone can lead to impingement or tensile stresses repeated stress or from trauma. rotator cuff tears in older patients. related to overhead sports. -

Arterial Supply to the Rotator Cuff Muscles

Int. J. Morphol., 32(1):136-140, 2014. Arterial Supply to the Rotator Cuff Muscles Suministro Arterial de los Músculos del Manguito Rotador N. Naidoo*; L. Lazarus*; B. Z. De Gama*; N. O. Ajayi* & K. S. Satyapal* NAIDOO, N.; LAZARUS, L.; DE GAMA, B. Z.; AJAYI, N. O. & SATYAPAL, K. S. Arterial supply to the rotator cuff muscles.Int. J. Morphol., 32(1):136-140, 2014. SUMMARY: The arterial supply to the rotator cuff muscles is generally provided by the subscapular, circumflex scapular, posterior circumflex humeral and suprascapular arteries. This study involved the bilateral dissection of the scapulohumeral region of 31 adult and 19 fetal cadaveric specimens. The subscapularis muscle was supplied by the subscapular, suprascapular and circumflex scapular arteries. The supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles were supplied by the suprascapular artery. The infraspinatus and teres minor muscles were found to be supplied by the circumflex scapular artery. In addition to the branches of these parent arteries, the rotator cuff muscles were found to be supplied by the dorsal scapular, lateral thoracic, thoracodorsal and posterior circumflex humeral arteries. The variations in the arterial supply to the rotator cuff muscles recorded in this study are unique and were not described in the literature reviewed. Due to the increased frequency of operative procedures in the scapulohumeral region, the knowledge of variations in the arterial supply to the rotator cuff muscles may be of practical importance to surgeons and radiologists. KEY WORDS: Arterial supply; Variations; Rotator cuff muscles; Parent arteries. INTRODUCTION (Abrassart et al.). In addition, the muscular parts of infraspinatus and teres minor muscles were supplied by the circumflex scapular artery while the tendinous parts of these The rotator cuff is a musculotendionous cuff formed muscles received branches from the posterior circumflex by the fusion of the tendons of four muscles – viz. -

Rotator Cuff Tears

OrthoInfo Basics Rotator Cuff Tears What is a rotator cuff? One of the Your rotator cuff helps you lift your arm, rotate it, and reach up over your head. most common middle-age It is made up of muscles and tendons in your shoulder. These struc- tures cover the head of your upper arm bone (humerus). This “cuff” complaints is holds the upper arm bone in the shoulder socket. shoulder pain. Rotator cuff tears come in all shapes and sizes. They typically occur A frequent in the tendon. source of that Partial tears. Many tears do not completely sever the soft tissue. Full thickness tears. A full or "complete" tear will split the soft pain is a torn tissue into two, sometimes detaching the tendon from the bone. rotator cuff. Rotator Cuff Bursa A torn rotator cuff will Tendon Clavicle (Collarbone) Humerus weaken your shoulder. (Upper Arm) This means that many Normal shoulder anatomy. daily activities, like combing your hair or Scapula getting dressed, may (Shoulder Blade) become painful and difficult to do. Rotator Cuff Tendon A complete tear of the rotator cuff tendon. 1 OrthoInfo Basics — Rotator Cuff Tears What causes rotator cuff tears? There are two main causes of rotator cuff repeating the same shoulder motions again and tears: injury and wear. again. Injury. If you fall down on your outstretched This explains why rotator cuff tears are most arm or lift something too heavy with a jerking common in people over 40 who participate in motion, you could tear your rotator cuff. This activities that have repetitive overhead type of tear can occur with other shoulder motions. -

Rotator Cuff 101 Every Year, More Than Two Million American Adults Seek Medical Care for Rotator Cuff Disease

BONE & JOINT BRIEFINGS Rotator Cuff 101 Every year, more than two million American adults seek medical care for rotator cuff disease. he rotator cuff is a series of 4 muscles It’s important to recognize that most people who surrounding the ball and socket joint of have shoulder pain don’t have a rotator cuff tear; the shoulder and plays a crucial role in there are many other causes. Pain from a rotator cuff optimizing shoulder function. The shoulder tear is usually experienced on the lateral aspect of the joint is inherently unstable, as the major arm, almost midway between the shoulder and the Tmuscles that move the shoulder around—the deltoid, elbow. It’s usually worse with overhead activity and the pectoralis, the back muscles—have a tendency worse at night. If this sort of pain is accompanied by to move the ball out of the center of the socket. The weakness, it probably should be checked right away. rotator cuff, almost as a counterforce against the If there’s no weakness involved, just aches and major muscles, helps to provide a stable fulcrum and pain, then ice, anti-inflammatory medication and a to optimize shoulder mechanics. couple of weeks of lighter activity could be all one As you might imagine, the muscles of the rotator needs. However, if the pain continues for more than a Christopher Gorczynski, MD cuff are subjected to quite a bit of stress. Friction couple of weeks, it deserves to be evaluated. Because and heavy usage (through sports or other repetitive the rotator cuff is under tension, tears generally get activity) can cause the tendons of the rotator cuff bigger over time and partial tears can become full- Those of us who are 30, to thicken or become inflamed and get “pinched” thickness tears. -

Guidelines for Returning to Weightlifting Following Shoulder Surgery

Guidelines for Returning to Weightlifting Following Shoulder Surgery Before initiating any type of weight training, you must have full range of motion of the shoulder and normal strength of the rotator cuff and scapular muscle groups. Your motion and strength should be tested by COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY your surgeon before beginning any weightlifting regimen. CENTER FOR SHOULDER, ELBOW AND SPORTS The following illustrates the approximate time table for beginning MEDICINE weight training following your particular surgery: Rotator Cuff Repair: 6 months Christopher S. Ahmad, MD Bankart Repair: 3 months Office (212) 305-5561 Labrum Repair: 4-6 months Fax (212) 305-4040 Arthroscopic Subacromial Decompression: 4-6 months Louis U. Bigliani, MD When beginning a weight training program, you should start with low Office (212) 305-5564 weights and with 3 sets of 15-20 repetitions. The high repetition sets Fax (212) 305-0999 will ensure that the weights you are using are not too heavy. NEVER perform any weightlifting exercise to the point of muscle failure. Edwin Cadet, MD Muscle failure occurs when the muscle is no longer able to provide the Office (212) 305-4626 energy necessary to contract and move the joints involved in the Fax (212) 305-4040 particular exercise. When muscle failure occurs, the risk for joint, muscle and tendon injuries is greatly increased. William N. Levine, MD Office (212) 305-0762 Exercises to AVOID: Fax (212) 305-4040 1. Triceps Dips 2. Chest Flies Appointment Scheduling 3. Pull-downs behind the neck (212) 305-4565 4. Wide grip bench press 5. Triceps press overhead Mailing Address: th 6. -

Chapter 5 the Shoulder Joint

The Shoulder Joint • Shoulder joint is attached to axial skeleton via the clavicle at SC joint • Scapula movement usually occurs with movement of humerus Chapter 5 – Humeral flexion & abduction require scapula The Shoulder Joint elevation, rotation upward, & abduction – Humeral adduction & extension results in scapula depression, rotation downward, & adduction Manual of Structural Kinesiology – Scapula abduction occurs with humeral internal R.T. Floyd, EdD, ATC, CSCS rotation & horizontal adduction – Scapula adduction occurs with humeral external rotation & horizontal abduction © McGraw-Hill Higher Education. All rights reserved. 5-1 © McGraw-Hill Higher Education. All rights reserved. 5-2 The Shoulder Joint Bones • Wide range of motion of the shoulder joint in • Scapula, clavicle, & humerus serve as many different planes requires a significant attachments for shoulder joint muscles amount of laxity – Scapular landmarks • Common to have instability problems • supraspinatus fossa – Rotator cuff impingement • infraspinatus fossa – Subluxations & dislocations • subscapular fossa • spine of the scapula • The price of mobility is reduced stability • glenoid cavity • The more mobile a joint is, the less stable it • coracoid process is & the more stable it is, the less mobile • acromion process • inferior angle © McGraw-Hill Higher Education. All rights reserved. 5-3 © McGraw-Hill Higher Education. All rights reserved. From Seeley RR, Stephens TD, Tate P: Anatomy and physiology , ed 7, 5-4 New York, 2006, McGraw-Hill Bones Bones • Scapula, clavicle, & humerus serve as • Key bony landmarks attachments for shoulder joint muscles – Acromion process – Humeral landmarks – Glenoid fossa • Head – Lateral border • Greater tubercle – Inferior angle • Lesser tubercle – Medial border • Intertubercular groove • Deltoid tuberosity – Superior angle – Spine of the scapula © McGraw-Hill Higher Education. -

Rotator Cuff Injuries

Scott Gudeman, MD 1260 Innovation Pkwy., Suite 100 Greenwood, IN 46143 317.884.5161 OrthoIndy.com ScottGudemanMD.com Rotator Cuff Injuries Front View Muscles of the Rotator Cuff Shoulder Anatomy Subscapularis Back The tendons of four muscles in the upper arm form View Supraspinatus the rotator cuff, blending together to help stabilize the shoulder. Tendons attach muscles to bone and are the mechanisms that enable muscles to move bones. It is because of the rotator cuff tendons, which connect the long bone of the arm (the humerus) to the scapula (the shoulder blade) that we can raise and rotate our arms. The rotator cuff also keeps the humerus tightly in Infraspinatus the socket (glenoid) when the arm is raised. The tough Supraspinatus fibers of the rotator cuff bend as the shoulder changes Teres position. Minor What are Rotator Cuff Injuries? For normal shoulder function, each muscle must be healthy, securely attached, coordinated and condi- tioned. When there are full or partial tears to the rotator cuff tendons, movement of the arm up or away from the body is impaired, making it difficult or impossible to rotate the arm in its ball-and-socket joint. Causes of Rotator Cuff Injuries Injuries to the rotator cuff tendons of the shoulder can happen to anyone over time. Rotator cuff tendons can be injured or torn by excessive force, such as pitching, lifting a very heavy object with the arm extended or trying to catch a heavy object as it falls. Occasionally, these accidents happen to young people, but typically a rotator cuff tear occurs to a person who is middle-aged or older who has experienced problems with the shoulder for some time before the injuring event. -

The Pattern of Idiopathic Isolated Teres Minor Atrophy with Regard to Its Two-Bundle Anatomy

Skeletal Radiology (2019) 48:363–374 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00256-018-3038-x SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE The pattern of idiopathic isolated teres minor atrophy with regard to its two-bundle anatomy Yusuhn Kang1 & Joong Mo Ahn1 & Choong Guen Chee1 & Eugene Lee1 & Joon Woo Lee1 & Heung Sik Kang1 Received: 1 May 2018 /Revised: 19 July 2018 /Accepted: 30 July 2018 /Published online: 8 August 2018 # ISS 2018 Abstract Objective We aimed to analyze the pattern of teres minor atrophy with regard to its two-bundle anatomy and to assess its association with clinical factors. Materials and methods Shoulder MRIs performed between January and December 2016 were retrospectively reviewed. Images were evaluated for the presence and pattern of isolated teres minor atrophy. Isolated teres minor atrophy was categorized into complete or partial pattern, and partial pattern was further classified according to the portion of the muscle that was predomi- nantly affected. The medical records were reviewed to identify clinical factors associated with teres minor atrophy. Results Seventy-eight shoulders out of 1,264 (6.2%) showed isolated teres minor atrophy; complete pattern in 41.0%, and partial pattern in 59.0%. Most cases of partial pattern had predominant involvement of the medial–dorsal component (82.6%). There was no significant association between teres minor atrophy and previous trauma, shoulder instability, osteoarthritis, and previous operation. The history of shoulder instability was more frequently found in patients with isolated teres minor atrophy (6.4%), compared with the control group (2.6%), although the difference was not statistically significant. Conclusion Isolated teres minor atrophy may be either complete or partial, and the partial pattern may involve either the medial– dorsal or the lateral–ventral component of the muscle. -

Strength Training for the Shoulder

175 Cambridge Street Boston, MA 02114 617-643-9999 www.mghsportsmedicine.org Strength Training for the Shoulder This handout is a guide to help you safely build strength and establish an effective weight- training program for the shoulder. Starting Your Weight Training Program • Start with three sets of 15-20 repetitions • Training with high repetition sets ensures that the weights that you are using are not too heavy. • To avoid injury, performing any weight training exercise to the point of muscle failure is not recommended. • “Muscle failure” occurs when, in performing a weight training exercise, the muscle is no longer able to provide the energy necessary to contract and move the joint(s) involved in the particular exercise. • Joint, muscle and tendon injuries are more likely to occur when muscle failure occurs. • Build up resistance and repetitions gradually • Perform exercises slowly, avoiding quick direction change • Exercise frequency should be 2 to 3 times per week for strength building • Be consistent and regular with the exercise schedule Prevention of Injuries in Weight Training • As a warm-up using light weights, you can do the rotator cuff and scapular strengthening program (see next page) • Follow a pre-exercise stretching routine (see next page) • Do warm-up sets for each weight exercise • Avoid overload and maximum lifts • Do not ‘work-through’ pain in the shoulder joint • Stretch as cool-down at end of exercise • Avoid excessive frequency and get adequate rest and recovery between sessions. • Caution: Do not do exercises with the barbell or dumbbell behind the head and neck. For shoulder safety when working with weights, you must always be able to see your hands if you are looking straight ahead. -

Rotator Cuff Repair with Biceps Tenotomy/Tenodesis

Brian Bjerke, MD Rotator Cuff Repair with Biceps Tenotomy/Tenodesis Post-Operative Protocol Phase I – Maximum Protection (Weeks 0 to 6): • Goals: o Reduce inflammation o Decrease pain o Postural education o PROM as instructed • Restrictions/Exercise Progression: o Sling for 6 weeks per Dr. Bjerke’s instructions ▪ Patients will be placed into an UltraSling post-operative (sling with the pillow) o Ice and modalities to reduce pain and inflammation o Cervical ROM and basic deep neck flexor activation (chin tucks) o Instruction on proper head, neck and shoulder alignment o Active hand and wrist ROM o Passive biceps x6 weeks (AAROM; no tenotomy or tenodesis) o Active shoulder retraction o Shoulder PROM progression ▪ No motion x2 weeks ▪ Passive flexion 0°-90° from weeks 2-4, then full ▪ External rotation 0°-30° from weeks 2-4, then full ▪ Avoid internal rotation (thumb up back) until 8 weeks post-op o Encourage walks and low intensity cardiovascular exercises to promote healing • Manual Intervention: o Soft tissue massage- global shoulder and CT junction o Scar tissue mobilization when incisions are healed o Graded GH mobilizations o ST mobilizations Phase II – Progressive Stretching and Active ROM (Weeks 6 to 8): • Goals: 1 o Discontinue sling as instructed o Postural education o Focus on posterior chain strengthening o Begin AROM o PROM/AAROM: ▪ Flexion 150°+ ▪ 30°-50° ER @ 0 abduction ▪ 45°-70° ER at 70-90 abduction ▪ • Exercise Progression: o Progress to full range of motion flexion and external rotation as tolerated ▪ Use a combination of wand, pulleys, wall walks or table slides to ensure compliance. -

Aandp1ch10lecture.Pdf

Chapter 10 Lecture Outline See separate PowerPoint slides for all figures and tables pre- inserted into PowerPoint without notes. Copyright © McGraw-Hill Education. Permission required for reproduction or display. 1 Introduction Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Education. Permission required for reproduction or display. • Muscles constitute nearly half of the body’s weight and are of central interest in several fields of health care and fitness Figure 10.5a 10-2 The Structural and Functional Organization of Muscles • Expected Learning Outcomes – Describe the varied functions of muscles. – Describe the connective tissue components of a muscle and their relationship to the bundling of muscle fibers. – Describe the various shapes of skeletal muscles and relate this to their functions. – Explain what is meant by the origin, insertion, belly, action, and innervation of a muscle. 10-3 The Structural and Functional Organization of Muscles (Continued) – Describe the ways that muscles work in groups to aid, oppose, or moderate each other’s actions. – Distinguish between intrinsic and extrinsic muscles. – Describe, in general terms, the nerve supply to the muscles and where these nerves originate. – Explain how the Latin names of muscles can aid in visualizing and remembering them. 10-4 The Structural and Functional Organization of Muscles • About 600 human skeletal muscles • Constitute about half of our body weight • Three kinds of muscle tissue – Skeletal, cardiac, smooth • Specialized for one major purpose – Converting the chemical energy in ATP -

Biceps Tenotomy Protocol

Department of Rehabilitation Services Physical Therapy Biceps Tenotomy Protocol The intent of this protocol is to provide the clinician with a guideline of the post- operative rehabilitation course of a patient that has undergone a Biceps Tenotomy for biceps dysfunction. It is no means intended to be a substitute for one’s clinical decision making regarding the progression of a patient’s post-operative course based on their physical exam/findings, individual progress, and/or the presence of post-operative complications. If a clinician requires assistance in the progression of a post-operative patient they should consult with the referring Surgeon. A biceps tenotomy procedure involves cutting of the long head of the biceps just prior to its insertion on the superior labrum. A biceps tenotomy is typically done when there is significant chronic long head of the biceps dysfunction or for definitive treatment of labral pathology with biceps anchor instability or for pain relief with irreparable massive rotator cuff tears. If the treating physical therapist needs to learn more about biceps tenotomy and rehabilitation we recommend reading: Krupp RJ. Kevern MA. Gaines MD. Kotara S. Singleton SB. Long Head of the Biceps Tendon Pain: Differential Diagnosis and Treatment. JOSPT. 2009; 39(2): 55-70. Progression to the next phase based on Clinical Criteria and/or Time Frames as Appropriate. Phase I – Passive Range of Motion Phase (starts approximately post op weeks 1- 2) Goals: Minimize shoulder pain and inflammatory response Achieve gradual restoration of passive range of motion (PROM) Enhance/ensure adequate scapular function Precautions/Patient Education: No active range of motion (AROM) of the elbow No excessive external rotation range of motion (ROM) / stretching.