ASMMR Newsletter Vol 2 Issue 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thebusinessofmotorsport ECONOMIC NEWS and ANALYSIS from the RACING WORLD

Contents: 2 November 2009 Doubts over Toyota future Renault for sale? Mercedes and McLaren: divorce German style USF1 confirms Aragon and Stubbs Issue 09.44 Senna signs for Campos New idea in Abu Dhabi Bridgestone to quit F1 at the end of 2010 Tom Wheatcroft A Silverstone deal close Graham Nearn Williams to confirm Barrichello and Hulkenberg this week Vettel in the twilight zone thebusinessofmotorsport ECONOMIC NEWS AND ANALYSIS FROM THE RACING WORLD Doubts over Toyota future Toyota is expected to announce later this week that it will be withdrawing from Formula 1 immediately. The company is believed to have taken the decision after indications in Japan that the automotive markets are not getting any better, Honda having recently announced a 56% drop in earnings in the last quarter, compared to 2008. Prior to that the company was looking at other options, such as selling the team on to someone else. This has now been axed and the company will simply close things down and settle all the necessary contractual commitments as quickly as possible. The news, if confirmed, will be another blow to the manufacturer power in F1 as it will be the third withdrawal by a major car company in 11 months, following in the footsteps of Honda and BMW. There are also doubts about the future of Renault's factory team. The news will also be a blow to the Formula One Teams' Association, although the members have learned that working together produces much better results than trying to take on the authorities alone. It also means that there are now just three manufacturers left: Ferrari, Mercedes and Renault, and engine supply from Cosworth will become essential to ensure there are sufficient engines to go around. -

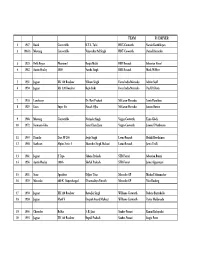

FIA Formula E Championship Round 3 - Punta Del Este Eprix Non Qualifying Practice 1

FIA Formula E Championship Round 3 - Punta del Este ePrix Non Qualifying Practice 1 Classification Official Timekeeper Nr. Driver Nat Team Car Time Lap Total Gap Kph 1 8 Nicolas Prost FRA Team e.dams Renault Spark - Renault SRT_01 E 1:16.696 19 20 - - 131.8 2 66 Daniel Abt DEU Audi Sport ABT Formula E Team Spark - Renault SRT_01 E 1:16.828 20 21 +0.132 +0.132 131.6 3 7 Jérôme D'Ambrosio BEL Dragon Racing Formula E Team Spark - Renault SRT_01 E 1:16.959 15 16 +0.263 +0.131 131.4 4 9 Sébastien Buemi CHE Team e.dams Renault Spark - Renault SRT_01 E 1:17.192 20 24 +0.496 +0.233 131.0 5 30 Stéphane Sarrazin FRA Venturi Formula E Team Spark - Renault SRT_01 E 1:17.222 16 24 +0.526 +0.030 130.9 6 27 Jean-Eric Vergne FRA Andretti Autosport Formula E Team Spark - Renault SRT_01 E 1:17.395 21 23 +0.699 +0.173 130.6 7 10 Jarno Trulli ITA Trulli Formula E Team Spark - Renault SRT_01 E 1:17.581 16 19 +0.885 +0.186 130.3 8 21 Bruno Senna BRA Mahindra Racing Formula E Team Spark - Renault SRT_01 E 1:17.628 23 24 +0.932 +0.047 130.2 9 28 Matthew Brabham USA Andretti Autosport Formula E Team Spark - Renault SRT_01 E 1:17.675 17 20 +0.979 +0.047 130.1 10 5 Karun Chandhok IND Mahindra Racing Formula E Team Spark - Renault SRT_01 E 1:17.999 20 21 +1.303 +0.324 129.6 11 6 Oriol Servià ESP Dragon Racing Formula E Team Spark - Renault SRT_01 E 1:18.013 16 21 +1.317 +0.014 129.6 12 55 Antonio Felix da Costa PRT Amlin Aguri Spark - Renault SRT_01 E 1:18.275 19 19 +1.579 +0.262 129.1 13 23 Nick Heidfeld DEU Venturi Formula E Team Spark - Renault SRT_01 E 1:18.319 -

Pukekohe Toyota

Traffic lights in Franklin County Pukekohe 3 Bridge club dresses to impress 4 NEWSTuesday, November 8, 2016 Pukekohe putsiton Pukekohe delivered a weekend of fast-car heaven as 106,753 supercar fans flocked to the spiritual home of New Zealand motorsport - Pukekohe Park - for the ITM Auckland Supersprint. It was an emotional finish to the three days of racing for Supercar championship leader, Kiwi Shane Van Gisbergen, (inset) as he claimed the Jason Richards Memorial Trophy, for recording the best results over the weekend’s event. Turn to P6-7 and P18-19 to check out all the action from the weekend. Photos: Daniel Kalisz, GETTY IMAGES SATURDAY 19 NOV 2016 The SsangYong Counties Cup returns to Pukekohe Park for 2016 showcasing thrilling horse racing, entertainment and hospitality. Featuring the Lone Star Pukekohe Fashion in the Field Book your tickets today www.PukekohePark.co.nz 2 FRANKLIN COUNTY NEWS, NOVEMBER 8, 2016 stuff.co.nz YOUR PAPER, YOUR PLACE 1. VALLEY SCHOOL GALA Valley School celebrates its 50th This newspaper is subject to NZ Press anniversary with a Golden Gala day Council procedures. FROM on November 12 from 10am-2pm. A complaint must first Face-painting, pony rides, quick-fire be directed in writing, THE raffles and more. within one month of EDITOR publication, to the editor’s email address. 2. COUNTIES CUP FASHION If not satisfied with the response, the complaint may be referred to the Pukekohe Lone Star Fashion in the Press Council. PO Box 10-879, Field will be held at SsangYong The Terrace, Wellington 6143. Counties Cup Day at Pukekohe Or use the online complaint form at There’s less than a month left to Park from 12pm on November 19. -

FOR the FIRST TIME BUEMI and DA COSTA STORM to VICTORY 26-Page Special “Formula E Goes South America“

January 2015 2nd volume Number 002 eNews FOR THE FIRST TIME BUEMI AND DA COSTA STORM TO VICTORY 26-page special “Formula E goes South America“ The big Formula E Social Media Analysis Pros and Cons: Minimum pit stop time Energy Recovery in Formula E Formula E testing in Uruguay GET CHARGED! How Qualcomm revolutionises our understanding of battery charging EDITORIAL| 01 365 BLANK PAGES - LET‘S WRITE SOME GOOD ONES appy new year everyone! Half of January is already gone and 2015 does not feel very new to me anymore but yet I am still highly moti- H vated. 2015 is going to be a great year, at least I am convinced of this. So you can see that my early year‘s optimisn still hasn‘t passed. 2015 is the year when Formula E finally makes its way to Europe and to e-racing.net‘s and my hometown - Berlin. We seriously cannot wait to have the electrifying Formula E buzz over here and thanks to our high-running motiva- The 2015 Berlin ePrix - we cannot wait! eNews release dates 2015 tion we will present you with a content-packed „Europe Special“ edition of eNews which will be released in time for the Monte Carlo ePrix. 16-01-2015 eNews 002 But the „European Special“ is not the only suprise we have 13-02-2015 eNews 003 in store for you. When we are all still drying our tears about 13-03-2015 eNews 004 the first Formula E season of all time ending, we will give you the amazing oppertunity to travel back in time and experience it all again - in our big „Formula E season review 14-03-2015 Miami ePrix 2014-2015“. -

N Views from the Group | December 2016

NEWS ‘N VIEWS FROM THE GROUP | DECEMBER 2016 CHAIRMAN UPDATE I’m sure you’re all interested in how our branches coped during the recent earthquakes, and it’s pleasing to report there was only minor damage to our Blenheim and Lower Hutt stores. Fortunately the main initial shake was at night, so all our staff were safe and are coping well, and both branches have since undergone engineering assessments and are back trading. The Plumbing World team are now working hard with our suppliers and freight companies to ensure we have the minimum of disruption while the country deals with a very sad and battered Kaikoura region, and our thoughts go out to everyone who has been affected. On a more positive note, thank you to all those who joined our results update webinar on 24 November, and it was a great opportunity to further share the details of both the improved financial performance, and the progress the NZPM co-op has made in the first half of the financial year. Our forecast for the second half of the year remains positive, so it’s great to see the initiatives that we’ve been implementing over the last 12-18 months are bearing fruit. This was our first webinar with shareholders, so we’d be delighted to receive your feedback on this format of communication with members. As I’ve mentioned in recent Connector articles, both the board and our executive team want to know how best to communicate with you, so any suggestions you have will be appreciated. -

Scalextric Aussie V8 Supercars: the Holdens! (Page 1 of 2)

Scalextric Aussie V8 Supercars: The Holdens! (Page 1 of 2) 25 of the 46 Supercars. Produced by the A.S.R.C.C. for the enjoyment of Club members! www.scalextricaustralia.com 2002 Holden 2003 Holden 2004 Holden 2005 Holden C2446 Castrol Perkins Racing C2519 Garry Rogers Motorsport C2612 Castrol Perkins Racing C2692 Paul Weel Racing Russell Ingall #8 (9th Place) Garth Tander #34 (12th Place) Steven Richards #11 (5th Place) Greg Murphy #51 (11th Place) 2006 Holden 2006 Holden 2007 Holden 2007 Holden C2768 Paul Weel Racing C2769 Tasman Motorsport C2832 Holden Racing Team C2954 HSV Dealer Team Greg Murphy #51 (24th Place) Jason Richards #3 (18th Place) Mark Skaife #2 (8th Place) Garth Tander #16 (Champion) 2009 Holden 2008 Holden 2010 Holden 2010 Holden C3040 Tasman Motorsport C3041 Holden Racing Team C3114 Holden Racing Team C3115 Paul Morris Motorsport Greg Murphy #51 (21st Place) Garth Tander #1 (3rd Place) Will Davison #22 (22nd Place) Russell Ingall #39 (12th Place) For enquiries on this poster please This poster is possible contact Dominic Grimes, President, with thanks to Scalextric, A.S.R.C.C.: Southern Model Supplies [email protected] & A.S.R.C.C. sponsors: (Version 2 9/9/20) www.slotshop.com.au www.slotscarsalive.com ) Scalextric Aussie V8 Supercars: The Holdens! (Page 2 of 2) 25 of the 46 Supercars. Produced by the A.S.R.C.C. for the enjoyment of Club members! www.scalextricaustralia.com 2010 Holden 2011 Holden 2012 Holden 2013 Holden C3161 Triple Eight Race Engineering C3227 Holden Racing Team C3322 Triple Eight Race -

Stewards Summary of Judicial Outcomes

STEWARDS SUMMARY OF JUDICIAL OUTCOMES Event Document: 46 2020 INTERNATIONAL VIRGIN AUSTRALIA SUPERCARS CHAMPIONSHIP RACES 13, 14 & 15 “BETEASY DARWIN TRIPLE CROWN” Hidden Valley Raceway, Darwin, Northern Territory 14th to 16th August 2020 STEWARDS SUMMARY OF JUDICIAL OUTCOMES, Update Final: Issued Sunday 16th August 2020 at 1815hrs. Sunday 16th August 2020 Matters from Race 15: Race Director Incident Determinations Following a request from DJR Team Penske, after the race the Race Director conducted a review of Car #88, Jamie Whincup, exiting its pit bay and Car #12 Fabian Coulthard entering its pit bay during their pit stops. The Race Director determined the matter did not warrant referral to the Stewards as no breach of the rules could be established on the available evidence. Stewards’ Decisions – Penalties imposed There were no penalties issued. Matters from Race 14: Race Director Incident Determinations There were no determinations Stewards’ Decisions – Penalties imposed There were no penalties issued. Matters from Qualifying for Race 15: Race Director Incident Determinations There were no determinations Stewards’ Decisions – Penalties imposed There were no penalties issued. Matters from Qualifying for Race 14: Race Director Incident Determinations There were no determinations Stewards’ Decisions – Penalties imposed There were no penalties issued. STEWARDS SUMMARY OF JUDICIAL OUTCOMES, Update #1: Issued Saturday 15th August 2020 at 1830hrs. Saturday 15th August 2020 Stewards Summary of Judicial Outcomes - Page 1 Information purposes only – no regulatory value Matters from Race 13: Race Director Incident Determinations There were no determinations Stewards’ Decisions – Penalties imposed The Stewards imposed a PLP on Car #97 Shane van Gisbergen, for contact to Car #8 Nick Percat. -

Driver Allocation.Pdf

TEAM F1 DRIVER 1 1947 Buick Convertible K.T.S. Tulsi HRT-Cosworth Narain Karthikeyan 2 1964½ Mustang Convertible Vijayendra Pal Singh HRT-Cosworth Daniel Ricciardo 3 1925 Rolls Royce Phantom I Ranjit Malik RBR Renault Sebastian Vettel 4 1962 Austin Healey 3000 Varsha Singh RBR Renault Mark Webber 5 1951 Jaguar XK 120 Roadster Vikram Singh Force India-Mercedes Adrian Sutil 6 1950 Jaguar XK 120 Roadster Rajiv Kehr Force India-Mercedes Paul Di Resta 7 1928 Lanchester Dr. Ravi Prakash McLaren-Mercedes Lewis Hamilton 8 1929 Essex Super Six Naresh Ojha McLaren-Mercedes Jenson Button 9 1968 Mustang Convertible Navinder Singh Virgin-Cosworth Timo Glock 10 1972 Karmann Ghia Sarat Chand Jain Virgin-Cosworth Jerome D'Ambrosio 11 1959 Diamler Dart SP 250 Avijit Singh Lotus-Renault Heikki Kovalainen 12 1960 Sunbeam Alpine Series I Shamsher Singh Shahani Lotus-Renault Jarno Trulli 13 1961 Jaguar E Type Sabena Prakash STR-Ferrari Sebastien Buemi 14 1956 Austin Healey 100/6 Shefali Prakash STR-Ferrari Jaime Alguersuari 15 1931 Stutz Speedster Diljeet Titus Mercedes GP Michael Schumacher 16 1929 Mercedes 680 K Supercharged Dharmaditya Patnaik Mercedes GP Nico Rosberg 17 1950 Jaguar XK 120 Roadster Bawa Jai Singh Williams-Cosworth Rubens Barrichello 18 1950 Jaguar Mark V Deepak Anand Mukarji Williams-Cosworth Pastor Maldonado 19 1956 Chevrolet BelAir S. B. Jatti Sauber-Ferrari Kamui Kobayashi 20 1955 Jaguar XK 140 Roadster Rupali Prakash Sauber-Ferrari Sergio Perez 21 1934 Lagonda M45 Ranajit Nobis Renault Bruno Senna 22 1935 Auburn Boattail Speedster Siddhraj Singh Renault Vitaly Petrov 23 1930 Studebaker Commander Awini Ambuj Shanker Ferrari Fernando Alonso 24 1931 Chrysler CM 6 Madan Mohan Yadav Ferrari Felipe Massa 25 1940 Sunbeam Talbot Rajwant Singh Grewal - - 26 1947 MG TC Yashvardhan Ruia - - 27 1963 Triumph TR 3B Fateh Singh - - 28 1956 Triumph TR 3 Harnal Arora - -. -

Video Name Track Track Location Date Year DVD # Classics #4001

Video Name Track Track Location Date Year DVD # Classics #4001 Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY D-0001 Victory Circle #4012, WG 1951 Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY D-0002 1959 Sports Car Grand Prix Weekend 1959 D-0003 A Gullwing at Twilight 1959 D-0004 At the IMRRC The Legacy of Briggs Cunningham Jr. 1959 D-0005 Legendary Bill Milliken talks about "Butterball" Nov 6,2004 1959 D-0006 50 Years of Formula 1 On-Board 1959 D-0007 WG: The Street Years Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY 1948 D-0008 25 Years at Speed: The Watkins Glen Story Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY 1972 D-0009 Saratoga Automobile Museum An Evening with Carroll Shelby D-0010 WG 50th Anniversary, Allard Reunion Watkins Glen, NY D-0011 Saturday Afternoon at IMRRC w/ Denise McCluggage Watkins Glen Watkins Glen October 1, 2005 2005 D-0012 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Festival Watkins Glen 2005 D-0013 1952 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Weekend Watkins Glen 1952 D-0014 1951-54 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Weekend Watkins Glen Watkins Glen 1951-54 D-0015 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Weekend 1952 Watkins Glen Watkins Glen 1952 D-0016 Ralph E. Miller Collection Watkins Glen Grand Prix 1949 Watkins Glen 1949 D-0017 Saturday Aternoon at the IMRRC, Lost Race Circuits Watkins Glen Watkins Glen 2006 D-0018 2005 The Legends Speeak Formula One past present & future 2005 D-0019 2005 Concours d'Elegance 2005 D-0020 2005 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Festival, Smalleys Garage 2005 D-0021 2005 US Vintange Grand Prix of Watkins Glen Q&A w/ Vic Elford 2005 D-0022 IMRRC proudly recognizes James Scaptura Watkins Glen 2005 D-0023 Saturday -

Driving Experience Public Speaking

Phone : +44 7900 885843 | [email protected] www.karunchandhok.com | www.twitter.com/karunchandhok | www.youtube.com/karunracing DRIVING EXPERIENCE 2018 Goodwood Revival: Whitsun Trophy, Fastest lap of the weekend across all categories. 2017 World Endurance Championship (selected rounds) and Le Mans: Tockwith Motorsport (LMP2). 9th in class at Le Mans British LMP3 Cup (Two races): T-Sport, 3rd and 4th places 2016 European Le Mans Series: Murphy Prototypes (LMP2) 2015 Le Mans 24 Hours: Murphy Prototypes, 5th in class (LMP2) Goodwood Revival St.Mary’s Trophy: Swiftune Mini, Top placed Mini in race 2014-2015 FIA Formula E Championship: Mahindra Racing, only Indian driver 2014 Dubai 24 Hours: Nissan GT Academy, 3rd in class (SP2) European Le Mans Series: Murphy Prototypes Le Mans 24 Hours: Murphy Prototypes 2013 Le Mans 24 Hours: Murphy Prototypes, 6th in class (LMP2) FIA GT Series: Seyffarth Motosport Goodwood Revival Tourist Trophy Race: Pearson Engineering, Jaguar E-Type 2012 World Endurance Championship: JRM Racing, 3rd in class (LMP1 Privateers) Le Mans 24 Hours: JRM Racing, 6th overall, 2nd in class (LMP1 Privateers), first Indian to race at Le Mans Race of Champions (Asia): Team India, 1st overall 2011 FIA Formula One World Championship: Team Lotus, race and reserve driver ; Simulator development driver 2010 FIA Formula One World Championship: Hispania Racing Team, race driver, only Indian in Championship ; Completed extensive simulator work at Mclaren simulator on behalf of Force India F1. 2009 Dubai 24 Hours: Empire Motorsports -

Rally Guideguide 1

26. - 28. 8. 2011 www.CzechRally.com RALLYRALLY GUIDEGUIDE 1 Vážení přátelé motoristického sportu, Barum Czech Rally Zlín má dlouholetou tradici, v letošním roce se bude konat již po jedenačtyřicáté. Rallysport je v České republice nesmírně populárním sportovním odvětvím, o čemž svědčí velké zástupy nadšených motoristických fandů podél rychlostních zkoušek, kterých se kolem trati jen schází několik desítek tisíc. Automobilová rally, která má centrum v moravském městě Zlíně, je od roku 1983 součástí mistrovství Evropy jezdců a od roku 2007 patří také do prestižního světového seriálu Intercontinental Rally Challenge (IRC) organizovaného s výraznou mediální podporou promotéra šampionátu, satelitní televizní stanice Eurosport. S jejím příchodem soutěž prošla dalším velkým posunem, který je patrný zejména na kvalitě startovního pole. To v minulém roce bylo bez nadsázky nejlepší v celé své historii - ve Zlíně se objevilo celkem 27 vozů progresivně se rozvíjející kategorie Super 2000. Tento počet jinde ve světě doposud nebyl dosud překonán a Zlín se může pyšnit tímto neoficiálním světovým rekordem. Vítězem loňského ročníku se podruhé stal Belgičan Freddy Loix, který se Škodou Fabií S2000 reprezentoval barvy domácí tovární stáje Škoda Motorsport. Dlouholetým partnerem Barum Czech Rally Zlín je tradiční česká pneumatikářská společnost Barum. Propojení nejúspěšnější domácí značky pneumatik s předním českým motoristickým závodem vytváří výhodné podmínky pro pozitivní vnímání jak pneumatik Barum, tak samotné soutěže. Stejně jako v minulosti bude značka Barum hlavním partnerem i při jedenačtyřicátém ročníku zlínské rally. Ta se během let propracovala až na samotný vrchol motoristických akcí v České republice a každoročně je nositelem řady novinek na scénu českého rallysportu. Pravidelné vysoké hodnocení rally z organizačního a především bezpečnostního hlediska přineslo zasloužené ocenění, neboť Světová rally komise při FIA zařadila Barum Czech Rally Zlín opět do seriálu elitních soutěží evropského šampionátu. -

Simoncelli, Di Meglio and Dunlop Celebrate in Style!

THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF DUNLOP MOTORSPORT IN TOUCH [ www.injection.tv ] ISSUE TEN, NOVEMBER 2008 Simoncelli, di Meglio and Dunlop celebrate in style! Marco Simoncelli and Alvaro Bautista have been the most consistent finishers in the MotoGP 250cc category, each scoring in 13 of the 15 races this year and are first and second in the riders' standings with one race remaining, in Valencia at the end of October. With his third place finish in Malaysia mid-October, seconds behind Bautista at the chequered flag, it was Simoncelli who was crowned the 2008 250cc champion and the Italian celebrated by completing a helmet-less victory lap around the track. Simoncelli has scored five wins to Bautista's four so far this year, but the Italian has consistently finished on the podium. Mid-season he was on devastating form, finishing second to Mika Kallio in France, and then winning the Spanish and German Grands Prix, finishing second in Britain, and third at the Dutch Grand Prix. Bautista had fallen far behind by the time the bikes lined up in Spain, having scored one win, but just 16 more points in the Mike di Meglio wins the Australian 125cc race and Dunlop's 12th straight category title opening six races. The Spaniard worked hard during the second half of the year, starting on his home ground where he was second to Simoncelli, and that led Dunlop celebrates another successful to a run of six straight podium finishes, culminating in victory in South Africa. The series was interrupted by Hurricane motorcycle racing season in 2008 Ike, which caused the cancellation of the Dunlop is celebrating another American 250cc Grand Prix, but in the Win number 50 came with performance.” next three races in Japan, Australia and fantastically successful season Valentino Rossi at the 1999 British “We thank the teams for putting Malaysia, Simoncelli again applied the in motor cycle racing.