1 Silencing Branched-Chain Ketoacid Dehydrogenase Or

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplemental Information to Mammadova-Bach Et Al., “Laminin Α1 Orchestrates VEGFA Functions in the Ecosystem of Colorectal Carcinogenesis”

Supplemental information to Mammadova-Bach et al., “Laminin α1 orchestrates VEGFA functions in the ecosystem of colorectal carcinogenesis” Supplemental material and methods Cloning of the villin-LMα1 vector The plasmid pBS-villin-promoter containing the 3.5 Kb of the murine villin promoter, the first non coding exon, 5.5 kb of the first intron and 15 nucleotides of the second villin exon, was generated by S. Robine (Institut Curie, Paris, France). The EcoRI site in the multi cloning site was destroyed by fill in ligation with T4 polymerase according to the manufacturer`s instructions (New England Biolabs, Ozyme, Saint Quentin en Yvelines, France). Site directed mutagenesis (GeneEditor in vitro Site-Directed Mutagenesis system, Promega, Charbonnières-les-Bains, France) was then used to introduce a BsiWI site before the start codon of the villin coding sequence using the 5’ phosphorylated primer: 5’CCTTCTCCTCTAGGCTCGCGTACGATGACGTCGGACTTGCGG3’. A double strand annealed oligonucleotide, 5’GGCCGGACGCGTGAATTCGTCGACGC3’ and 5’GGCCGCGTCGACGAATTCACGC GTCC3’ containing restriction site for MluI, EcoRI and SalI were inserted in the NotI site (present in the multi cloning site), generating the plasmid pBS-villin-promoter-MES. The SV40 polyA region of the pEGFP plasmid (Clontech, Ozyme, Saint Quentin Yvelines, France) was amplified by PCR using primers 5’GGCGCCTCTAGATCATAATCAGCCATA3’ and 5’GGCGCCCTTAAGATACATTGATGAGTT3’ before subcloning into the pGEMTeasy vector (Promega, Charbonnières-les-Bains, France). After EcoRI digestion, the SV40 polyA fragment was purified with the NucleoSpin Extract II kit (Machery-Nagel, Hoerdt, France) and then subcloned into the EcoRI site of the plasmid pBS-villin-promoter-MES. Site directed mutagenesis was used to introduce a BsiWI site (5’ phosphorylated AGCGCAGGGAGCGGCGGCCGTACGATGCGCGGCAGCGGCACG3’) before the initiation codon and a MluI site (5’ phosphorylated 1 CCCGGGCCTGAGCCCTAAACGCGTGCCAGCCTCTGCCCTTGG3’) after the stop codon in the full length cDNA coding for the mouse LMα1 in the pCIS vector (kindly provided by P. -

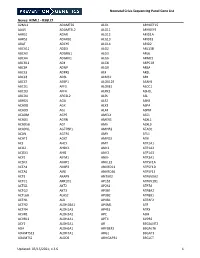

Gene Symbol Gene Description ACVR1B Activin a Receptor, Type IB

Table S1. Kinase clones included in human kinase cDNA library for yeast two-hybrid screening Gene Symbol Gene Description ACVR1B activin A receptor, type IB ADCK2 aarF domain containing kinase 2 ADCK4 aarF domain containing kinase 4 AGK multiple substrate lipid kinase;MULK AK1 adenylate kinase 1 AK3 adenylate kinase 3 like 1 AK3L1 adenylate kinase 3 ALDH18A1 aldehyde dehydrogenase 18 family, member A1;ALDH18A1 ALK anaplastic lymphoma kinase (Ki-1) ALPK1 alpha-kinase 1 ALPK2 alpha-kinase 2 AMHR2 anti-Mullerian hormone receptor, type II ARAF v-raf murine sarcoma 3611 viral oncogene homolog 1 ARSG arylsulfatase G;ARSG AURKB aurora kinase B AURKC aurora kinase C BCKDK branched chain alpha-ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase BMPR1A bone morphogenetic protein receptor, type IA BMPR2 bone morphogenetic protein receptor, type II (serine/threonine kinase) BRAF v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1 BRD3 bromodomain containing 3 BRD4 bromodomain containing 4 BTK Bruton agammaglobulinemia tyrosine kinase BUB1 BUB1 budding uninhibited by benzimidazoles 1 homolog (yeast) BUB1B BUB1 budding uninhibited by benzimidazoles 1 homolog beta (yeast) C9orf98 chromosome 9 open reading frame 98;C9orf98 CABC1 chaperone, ABC1 activity of bc1 complex like (S. pombe) CALM1 calmodulin 1 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) CALM2 calmodulin 2 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) CALM3 calmodulin 3 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) CAMK1 calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase I CAMK2A calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaM kinase) II alpha CAMK2B calcium/calmodulin-dependent -

Supplement 1 Overview of Dystonia Genes

Supplement 1 Overview of genes that may cause dystonia in children and adolescents Gene (OMIM) Disease name/phenotype Mode of inheritance 1: (Formerly called) Primary dystonias (DYTs): TOR1A (605204) DYT1: Early-onset generalized AD primary torsion dystonia (PTD) TUBB4A (602662) DYT4: Whispering dystonia AD GCH1 (600225) DYT5: GTP-cyclohydrolase 1 AD deficiency THAP1 (609520) DYT6: Adolescent onset torsion AD dystonia, mixed type PNKD/MR1 (609023) DYT8: Paroxysmal non- AD kinesigenic dyskinesia SLC2A1 (138140) DYT9/18: Paroxysmal choreoathetosis with episodic AD ataxia and spasticity/GLUT1 deficiency syndrome-1 PRRT2 (614386) DYT10: Paroxysmal kinesigenic AD dyskinesia SGCE (604149) DYT11: Myoclonus-dystonia AD ATP1A3 (182350) DYT12: Rapid-onset dystonia AD parkinsonism PRKRA (603424) DYT16: Young-onset dystonia AR parkinsonism ANO3 (610110) DYT24: Primary focal dystonia AD GNAL (139312) DYT25: Primary torsion dystonia AD 2: Inborn errors of metabolism: GCDH (608801) Glutaric aciduria type 1 AR PCCA (232000) Propionic aciduria AR PCCB (232050) Propionic aciduria AR MUT (609058) Methylmalonic aciduria AR MMAA (607481) Cobalamin A deficiency AR MMAB (607568) Cobalamin B deficiency AR MMACHC (609831) Cobalamin C deficiency AR C2orf25 (611935) Cobalamin D deficiency AR MTRR (602568) Cobalamin E deficiency AR LMBRD1 (612625) Cobalamin F deficiency AR MTR (156570) Cobalamin G deficiency AR CBS (613381) Homocysteinuria AR PCBD (126090) Hyperphelaninemia variant D AR TH (191290) Tyrosine hydroxylase deficiency AR SPR (182125) Sepiaterine reductase -

Protein Identities in Evs Isolated from U87-MG GBM Cells As Determined by NG LC-MS/MS

Protein identities in EVs isolated from U87-MG GBM cells as determined by NG LC-MS/MS. No. Accession Description Σ Coverage Σ# Proteins Σ# Unique Peptides Σ# Peptides Σ# PSMs # AAs MW [kDa] calc. pI 1 A8MS94 Putative golgin subfamily A member 2-like protein 5 OS=Homo sapiens PE=5 SV=2 - [GG2L5_HUMAN] 100 1 1 7 88 110 12,03704523 5,681152344 2 P60660 Myosin light polypeptide 6 OS=Homo sapiens GN=MYL6 PE=1 SV=2 - [MYL6_HUMAN] 100 3 5 17 173 151 16,91913397 4,652832031 3 Q6ZYL4 General transcription factor IIH subunit 5 OS=Homo sapiens GN=GTF2H5 PE=1 SV=1 - [TF2H5_HUMAN] 98,59 1 1 4 13 71 8,048185945 4,652832031 4 P60709 Actin, cytoplasmic 1 OS=Homo sapiens GN=ACTB PE=1 SV=1 - [ACTB_HUMAN] 97,6 5 5 35 917 375 41,70973209 5,478027344 5 P13489 Ribonuclease inhibitor OS=Homo sapiens GN=RNH1 PE=1 SV=2 - [RINI_HUMAN] 96,75 1 12 37 173 461 49,94108966 4,817871094 6 P09382 Galectin-1 OS=Homo sapiens GN=LGALS1 PE=1 SV=2 - [LEG1_HUMAN] 96,3 1 7 14 283 135 14,70620005 5,503417969 7 P60174 Triosephosphate isomerase OS=Homo sapiens GN=TPI1 PE=1 SV=3 - [TPIS_HUMAN] 95,1 3 16 25 375 286 30,77169764 5,922363281 8 P04406 Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase OS=Homo sapiens GN=GAPDH PE=1 SV=3 - [G3P_HUMAN] 94,63 2 13 31 509 335 36,03039959 8,455566406 9 Q15185 Prostaglandin E synthase 3 OS=Homo sapiens GN=PTGES3 PE=1 SV=1 - [TEBP_HUMAN] 93,13 1 5 12 74 160 18,68541938 4,538574219 10 P09417 Dihydropteridine reductase OS=Homo sapiens GN=QDPR PE=1 SV=2 - [DHPR_HUMAN] 93,03 1 1 17 69 244 25,77302971 7,371582031 11 P01911 HLA class II histocompatibility antigen, -

1 Silencing Branched-Chain Ketoacid Dehydrogenase Or

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.21.960153; this version posted February 22, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Silencing branched-chain ketoacid dehydrogenase or treatment with branched-chain ketoacids ex vivo inhibits muscle insulin signaling Running title: BCKAs impair insulin signaling Dipsikha Biswas1, PhD, Khoi T. Dao1, BSc, Angella Mercer1, BSc, Andrew Cowie1 , BSc, Luke Duffley1, BSc, Yassine El Hiani2, PhD, Petra C. Kienesberger1, PhD, Thomas Pulinilkunnil1†, PhD 1Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Dalhousie Medicine New Brunswick, Saint John, New Brunswick, Canada, 2Department of Physiology and Biophysics, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. †Correspondence to Thomas Pulinilkunnil, PhD Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Faculty of Medicine, Dalhousie University Dalhousie Medicine New Brunswick, 100 Tucker Park Road, Saint John E2L4L5, New Brunswick, Canada. Telephone: (506) 636-6973; Fax: (506) 636-6001; email: [email protected]. 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.21.960153; this version posted February 22, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International -

Application of a MYC Degradation

SCIENCE SIGNALING | RESEARCH ARTICLE CANCER Copyright © 2019 The Authors, some rights reserved; Application of a MYC degradation screen identifies exclusive licensee American Association sensitivity to CDK9 inhibitors in KRAS-mutant for the Advancement of Science. No claim pancreatic cancer to original U.S. Devon R. Blake1, Angelina V. Vaseva2, Richard G. Hodge2, McKenzie P. Kline3, Thomas S. K. Gilbert1,4, Government Works Vikas Tyagi5, Daowei Huang5, Gabrielle C. Whiten5, Jacob E. Larson5, Xiaodong Wang2,5, Kenneth H. Pearce5, Laura E. Herring1,4, Lee M. Graves1,2,4, Stephen V. Frye2,5, Michael J. Emanuele1,2, Adrienne D. Cox1,2,6, Channing J. Der1,2* Stabilization of the MYC oncoprotein by KRAS signaling critically promotes the growth of pancreatic ductal adeno- carcinoma (PDAC). Thus, understanding how MYC protein stability is regulated may lead to effective therapies. Here, we used a previously developed, flow cytometry–based assay that screened a library of >800 protein kinase inhibitors and identified compounds that promoted either the stability or degradation of MYC in a KRAS-mutant PDAC cell line. We validated compounds that stabilized or destabilized MYC and then focused on one compound, Downloaded from UNC10112785, that induced the substantial loss of MYC protein in both two-dimensional (2D) and 3D cell cultures. We determined that this compound is a potent CDK9 inhibitor with a previously uncharacterized scaffold, caused MYC loss through both transcriptional and posttranslational mechanisms, and suppresses PDAC anchorage- dependent and anchorage-independent growth. We discovered that CDK9 enhanced MYC protein stability 62 through a previously unknown, KRAS-independent mechanism involving direct phosphorylation of MYC at Ser . -

Transglutaminase-Catalyzed Inactivation Of

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 94, pp. 12604–12609, November 1997 Medical Sciences Transglutaminase-catalyzed inactivation of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase and a-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex by polyglutamine domains of pathological length ARTHUR J. L. COOPER*†‡§, K.-F. REX SHEU†‡,JAMES R. BURKE¶i,OSAMU ONODERA¶i, WARREN J. STRITTMATTER¶i,**, ALLEN D. ROSES¶i,**, AND JOHN P. BLASS†‡,†† Departments of *Biochemistry, †Neurology and Neuroscience, and ††Medicine, Cornell University Medical College, New York, NY 10021; ‡Burke Medical Research Institute, Cornell University Medical College, White Plains, NY 10605; and Departments of ¶Medicine, **Neurobiology, and iDeane Laboratory, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC 27710 Edited by Louis Sokoloff, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, and approved August 28, 1997 (received for review April 24, 1997) ABSTRACT Several adult-onset neurodegenerative dis- Q12-containing peptide (16). In the work of Kahlem et al. (16) the eases are caused by genes with expanded CAG triplet repeats largest Qn domain studied was Q18. We found that both a within their coding regions and extended polyglutamine (Qn) nonpathological-length Qn domain (n 5 10) and a longer, patho- domains within the expressed proteins. Generally, in clinically logical-length Qn domain (n 5 62) are excellent substrates of affected individuals n > 40. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehy- tTGase (17, 18). drogenase binds tightly to four Qn disease proteins, but the Burke et al. (1) showed that huntingtin, huntingtin-derived significance of this interaction is unknown. We now report that fragments, and the dentatorubralpallidoluysian atrophy protein purified glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase is inacti- bind selectively to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase vated by tissue transglutaminase in the presence of glutathione (GAPDH) in human brain homogenates and to immobilized S-transferase constructs containing a Qn domain of pathological rabbit muscle GAPDH. -

NICU Gene List Generator.Xlsx

Neonatal Crisis Sequencing Panel Gene List Genes: A2ML1 - B3GLCT A2ML1 ADAMTS9 ALG1 ARHGEF15 AAAS ADAMTSL2 ALG11 ARHGEF9 AARS1 ADAR ALG12 ARID1A AARS2 ADARB1 ALG13 ARID1B ABAT ADCY6 ALG14 ARID2 ABCA12 ADD3 ALG2 ARL13B ABCA3 ADGRG1 ALG3 ARL6 ABCA4 ADGRV1 ALG6 ARMC9 ABCB11 ADK ALG8 ARPC1B ABCB4 ADNP ALG9 ARSA ABCC6 ADPRS ALK ARSL ABCC8 ADSL ALMS1 ARX ABCC9 AEBP1 ALOX12B ASAH1 ABCD1 AFF3 ALOXE3 ASCC1 ABCD3 AFF4 ALPK3 ASH1L ABCD4 AFG3L2 ALPL ASL ABHD5 AGA ALS2 ASNS ACAD8 AGK ALX3 ASPA ACAD9 AGL ALX4 ASPM ACADM AGPS AMELX ASS1 ACADS AGRN AMER1 ASXL1 ACADSB AGT AMH ASXL3 ACADVL AGTPBP1 AMHR2 ATAD1 ACAN AGTR1 AMN ATL1 ACAT1 AGXT AMPD2 ATM ACE AHCY AMT ATP1A1 ACO2 AHDC1 ANK1 ATP1A2 ACOX1 AHI1 ANK2 ATP1A3 ACP5 AIFM1 ANKH ATP2A1 ACSF3 AIMP1 ANKLE2 ATP5F1A ACTA1 AIMP2 ANKRD11 ATP5F1D ACTA2 AIRE ANKRD26 ATP5F1E ACTB AKAP9 ANTXR2 ATP6V0A2 ACTC1 AKR1D1 AP1S2 ATP6V1B1 ACTG1 AKT2 AP2S1 ATP7A ACTG2 AKT3 AP3B1 ATP8A2 ACTL6B ALAS2 AP3B2 ATP8B1 ACTN1 ALB AP4B1 ATPAF2 ACTN2 ALDH18A1 AP4M1 ATR ACTN4 ALDH1A3 AP4S1 ATRX ACVR1 ALDH3A2 APC AUH ACVRL1 ALDH4A1 APTX AVPR2 ACY1 ALDH5A1 AR B3GALNT2 ADA ALDH6A1 ARFGEF2 B3GALT6 ADAMTS13 ALDH7A1 ARG1 B3GAT3 ADAMTS2 ALDOB ARHGAP31 B3GLCT Updated: 03/15/2021; v.3.6 1 Neonatal Crisis Sequencing Panel Gene List Genes: B4GALT1 - COL11A2 B4GALT1 C1QBP CD3G CHKB B4GALT7 C3 CD40LG CHMP1A B4GAT1 CA2 CD59 CHRNA1 B9D1 CA5A CD70 CHRNB1 B9D2 CACNA1A CD96 CHRND BAAT CACNA1C CDAN1 CHRNE BBIP1 CACNA1D CDC42 CHRNG BBS1 CACNA1E CDH1 CHST14 BBS10 CACNA1F CDH2 CHST3 BBS12 CACNA1G CDK10 CHUK BBS2 CACNA2D2 CDK13 CILK1 BBS4 CACNB2 CDK5RAP2 -

Abstracts from the 50Th European Society of Human Genetics Conference: Electronic Posters

European Journal of Human Genetics (2019) 26:820–1023 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-018-0248-6 ABSTRACT Abstracts from the 50th European Society of Human Genetics Conference: Electronic Posters Copenhagen, Denmark, May 27–30, 2017 Published online: 1 October 2018 © European Society of Human Genetics 2018 The ESHG 2017 marks the 50th Anniversary of the first ESHG Conference which took place in Copenhagen in 1967. Additional information about the event may be found on the conference website: https://2017.eshg.org/ Sponsorship: Publication of this supplement is sponsored by the European Society of Human Genetics. All authors were asked to address any potential bias in their abstract and to declare any competing financial interests. These disclosures are listed at the end of each abstract. Contributions of up to EUR 10 000 (ten thousand euros, or equivalent value in kind) per year per company are considered "modest". Contributions above EUR 10 000 per year are considered "significant". 1234567890();,: 1234567890();,: E-P01 Reproductive Genetics/Prenatal and fetal echocardiography. The molecular karyotyping Genetics revealed a gain in 8p11.22-p23.1 region with a size of 27.2 Mb containing 122 OMIM gene and a loss in 8p23.1- E-P01.02 p23.3 region with a size of 6.8 Mb containing 15 OMIM Prenatal diagnosis in a case of 8p inverted gene. The findings were correlated with 8p inverted dupli- duplication deletion syndrome cation deletion syndrome. Conclusion: Our study empha- sizes the importance of using additional molecular O¨. Kırbıyık, K. M. Erdog˘an, O¨.O¨zer Kaya, B. O¨zyılmaz, cytogenetic methods in clinical follow-up of complex Y. -

Aerobic Glycolysis Fuels Platelet Activation: Small-Molecule Modulators of Platelet Metabolism As Anti-Thrombotic Agents

ARTICLE Platelet Biology & its Disorders Aerobic glycolysis fuels platelet activation: Ferrata Storti Foundation small-molecule modulators of platelet metabolism as anti-thrombotic agents Paresh P. Kulkarni,1† Arundhati Tiwari,1† Nitesh Singh,1 Deepa Gautam,1 Vijay K. Sonkar,1 Vikas Agarwal2 and Debabrata Dash1 1Department of Biochemistry, Institute of Medical Sciences and 2Department of Cardiology, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, Uttar Haematologica 2019 Pradesh, India Volume 104(4):806-818 † PPK and AT contributed equally to this work. ABSTRACT latelets are critical to arterial thrombosis, which underlies myocardial infarction and stroke. Activated platelets, regardless of the nature of Ptheir stimulus, initiate energy-intensive processesthat sustain throm- bus, while adapting to potential adversities of hypoxia and nutrient depri- vation within the densely packed thrombotic milieu. We report here that stimulated platelets switch their energy metabolism to robicae glycolysis by modulating enzymes at key checkpoints in glucose metabolism. We found that aerobic glycolysis, in turn, accelerates flux through the pentose phos- phate pathway and supports platelet activation. Hence, reversing metabolic adaptations of platelets could be an effective alternative to conventional anti-platelet approaches, which are crippled by remarkable redundancy in platelet agonists and ensuing signaling pathways. In support of this hypoth- esis, small-molecule modulators of pyruvate dehydrogenase, pyruvate kinase M2 and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, all of which impede aerobic glycolysis and/or the pentose phosphate pathway, restrained the Correspondence: agonist-induced platelet responsesex vivo. These drugs, which include the DEBABRATA DASH anti-neoplastic candidate, dichloroacetate, and the Food and Drug [email protected] Administration-approved dehydroepiandrosterone, profoundly impaired thrombosis in mice, thereby exhibiting potential as anti-thrombotic agents. -

A Novel Whole Gene Deletion of BCKDHB by Alu-Mediated Non-Allelic Recombination in a Chinese Patient with Maple Syrup Urine Disease

fgene-09-00145 April 21, 2018 Time: 11:38 # 1 CASE REPORT published: 24 April 2018 doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00145 A Novel Whole Gene Deletion of BCKDHB by Alu-Mediated Non-allelic Recombination in a Chinese Patient With Maple Syrup Urine Disease Gang Liu1†, Dingyuan Ma1†, Ping Hu1, Wen Wang2, Chunyu Luo1, Yan Wang1, Yun Sun1, Jingjing Zhang1, Tao Jiang1* and Zhengfeng Xu1* 1 State Key Laboratory of Reproductive Medicine, Department of Prenatal Diagnosis, The Affiliated Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing Maternity and Child Health Care Hospital, Nanjing, China, 2 Reproductive Genetic Center, Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University, Xuzhou, China Edited by: Musharraf Jelani, Maple syrup urine disease (MSUD) is an autosomal recessive inherited metabolic King Abdulaziz University, disorder caused by mutations in the BCKDHA, BCKDHB, DBT, and DLD genes. Among Saudi Arabia the wide range of disease-causing mutations in BCKDHB, only one large deletion has Reviewed by: Michael L. Raff, been associated with MSUD. Compound heterozygous mutations in BCKDHB were MultiCare Health System, identified in a Chinese patient with typical MSUD using next-generation sequencing, United States quantitative PCR, and array comparative genomic hybridization. One allele presented Bruna De Felice, Università degli Studi della Campania a missense mutation (c.391G > A), while the other allele had a large deletion; both “Luigi Vanvitelli”, Italy were inherited from the patient’s unaffected parents. The deletion breakpoints were *Correspondence: characterized using long-range PCR and sequencing. A novel 383,556 bp deletion Tao Jiang [email protected] (chr6: g.80811266_81194921del) was determined, which encompassed the entire Zhengfeng Xu BCKDHB gene. -

Emerging Roles of P53 Family Members in Glucose Metabolism

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Emerging Roles of p53 Family Members in Glucose Metabolism Yoko Itahana and Koji Itahana * Cancer and Stem Cell Biology Program, Duke-NUS Medical School, 8 College Road, Singapore 169857, Singapore; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +65-6516-2554; Fax: +65-6221-2402 Received: 19 January 2018; Accepted: 22 February 2018; Published: 8 March 2018 Abstract: Glucose is the key source for most organisms to provide energy, as well as the key source for metabolites to generate building blocks in cells. The deregulation of glucose homeostasis occurs in various diseases, including the enhanced aerobic glycolysis that is observed in cancers, and insulin resistance in diabetes. Although p53 is thought to suppress tumorigenesis primarily by inducing cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and senescence in response to stress, the non-canonical functions of p53 in cellular energy homeostasis and metabolism are also emerging as critical factors for tumor suppression. Increasing evidence suggests that p53 plays a significant role in regulating glucose homeostasis. Furthermore, the p53 family members p63 and p73, as well as gain-of-function p53 mutants, are also involved in glucose metabolism. Indeed, how this protein family regulates cellular energy levels is complicated and difficult to disentangle. This review discusses the roles of the p53 family in multiple metabolic processes, such as glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, aerobic respiration, and autophagy. We also discuss how the dysregulation of the p53 family in these processes leads to diseases such as cancer and diabetes. Elucidating the complexities of the p53 family members in glucose homeostasis will improve our understanding of these diseases.