HW Longfellow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zukofsky), 736–37 , 742–43 Asian American Poetry As, 987–88 “ABC” (Justice), 809–11 “Benefi T” Readings, 1137–138 Abolitionism

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00336-1 - The Cambridge History of: American Poetry Edited by Alfred Bendixen and Stephen Burt Index More information Index “A” (Zukofsky), 736–37 , 742–43 Asian American poetry as, 987–88 “ABC” (Justice), 809–11 “benefi t” readings, 1137–138 abolitionism. See also slavery multilingual poetry and, 1133–134 in African American poetry, 293–95 , 324 Adam, Helen, 823–24 in Longfellow’s poetry, 241–42 , 249–52 Adams, Charles Follen, 468 in mid-nineteenth-century poetry, Adams, Charles Frances, 468 290–95 Adams, John, 140 , 148–49 in Whittier’s poetry, 261–67 Adams, L é onie, 645 , 1012–1013 in women’s poetry, 185–86 , 290–95 Adcock, Betty, 811–13 , 814 Abraham Lincoln: An Horatian Ode “Address to James Oglethorpe, An” (Stoddard), 405 (Kirkpatrick), 122–23 Abrams, M. H., 1003–1004 , 1098 “Address to Miss Phillis Wheatley, academic verse Ethiopian Poetess, Who Came literary canon and, 2 from Africa at Eight Year of Age, southern poetry and infl uence of, 795–96 and Soon Became Acquainted with Academy for Negro Youth (Baltimore), the Gospel of Jesus Christ, An” 293–95 (Hammon), 138–39 “Academy in Peril: William Carlos “Adieu to Norman, Bonjour to Joan and Williams Meets the MLA, The” Jean-Paul” (O’Hara), 858–60 (Bernstein), 571–72 Admirable Crichton, The (Barrie), Academy of American Poets, 856–64 , 790–91 1135–136 Admonitions (Spicer), 836–37 Bishop’s fellowship from, 775 Adoff , Arnold, 1118 prize to Moss by, 1032 “Adonais” (Shelley), 88–90 Acadians, poetry about, 37–38 , 241–42 , Adorno, Theodor, 863 , 1042–1043 252–54 , 264–65 Adulateur, The (Warren), 134–35 Accent (television show), 1113–115 Adventure (Bryher), 613–14 “Accountability” (Dunbar), 394 Adventures of Daniel Boone, The (Bryan), Ackerman, Diane, 932–33 157–58 Á coma people, in Spanish epic Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Twain), poetry, 49–50 183–86 Active Anthology (Pound), 679 funeral elegy ridiculed in, 102–04 activist poetry. -

Report 2011–5010

Shahejie−Shahejie/Guantao/Wumishan and Carboniferous/Permian Coal−Paleozoic Total Petroleum Systems in the Bohaiwan Basin, China (based on geologic studies for the 2000 World Energy Assessment Project of the U.S. Geological Survey) 114° 122° Heilongjiang 46° Mongolia Jilin Nei Mongol Liaoning Liao He Hebei North Korea Beijing Korea Bohai Bay Bohaiwan Bay 38° Basin Shanxi Huang He Shandong Yellow Sea Henan Jiangsu 0 200 MI Anhui 0 200 KM Hubei Shanghai Scientific Investigations Report 2011–5010 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Shahejie−Shahejie/Guantao/Wumishan and Carboniferous/Permian Coal−Paleozoic Total Petroleum Systems in the Bohaiwan Basin, China (based on geologic studies for the 2000 World Energy Assessment Project of the U.S. Geological Survey) By Robert T. Ryder, Jin Qiang, Peter J. McCabe, Vito F. Nuccio, and Felix Persits Scientific Investigations Report 2011–5010 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2012 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. -

The Legacy of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Maine History Volume 27 Number 4 Article 4 4-1-1988 The Legacy of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Daniel Aaron Harvard University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistoryjournal Part of the Modern Literature Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Aaron, Daniel. "The Legacy of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow." Maine History 27, 4 (1988): 42-67. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistoryjournal/vol27/iss4/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DANIEL AARON THE LEGACY OF HENRY WADSWORTH LONGFELLOW Once upon a time (and it wasn’t so long ago), the so-called “household” or “Fire-Side” poets pretty much made up what Barrett Wendell of Harvard University called “the literature of America.” Wendell devoted almost half of his still readable survey, published in 1900, to New England writers. Some of them would shortly be demoted by a new generation of critics, but at the moment, they still constituted “American literature” in the popular mind. The “Boston constellation” — that was Henry James’s term for them — had watched the country coalesce from a shaky union of states into a transcontinental nation. They had lived through the crisis of civil war and survived, loved, and honored. Multitudes recognized their bearded benevolent faces; generations of school children memorized and recited stanzas of their iconic poems. Among these hallowed men of letters, Longfellow was the most popular, the most beloved, the most revered. -

Lyrical Liberators Contents

LYRICAL LIBERATORS CONTENTS List of Illustrations xiii Acknowledgments xv Introduction 1 1. Calls for Action 18 2. The Murder of Elijah P. Lovejoy 41 3. Fugitive Slaves 47 4. The Assault on Senator Charles Sumner 108 5. John Brown and the Raid on Harpers Ferry 116 6. Slaves and Death 136 7. Slave Mothers 156 8. The South 170 9. Equality 213 10. Freedom 226 11. Atonement 252 12. Wartime 289 13. Emancipation, the Proclamation, and the Thirteenth Amendment 325 Notes 345 Works Cited 353 General Index 359 Index of Poem Titles 367 Index of Poets 371 xi INTRODUCTION he problematic issue of slavery would appear not to lend itself to po- etry, yet in truth nothing would have seemed more natural to nineteenth- T century Americans. Poetry meant many different things at the time—it was at once art form, popular entertainment, instructional medium, and forum for sociopolitical commentary. The poems that appeared in periodicals of the era are therefore integral to our understanding of how the populace felt about any issue of consequence. Writers seized on this uniquely persuasive genre to win readers over to their cause, and perhaps most memorable among them are the abolitionists. Antislavery activists turned to poetry so as to connect both emotionally and rationally with a wide audience on a regular basis. By speaking out on behalf of those who could not speak for themselves, their poems were one of the most effective means of bearing witness to, and thus also protesting, a reprehensible institution. These pleas for justice proved ef- fective by insisting on the right of freedom of speech at a time when it ap- peared to be in jeopardy. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. ■UMIAccessing the Worlds Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8726748 Black 'women abolitionists: A study of gender and race in the American antislavery movement, 1828-1800 Yee, Shirley Jo>ann, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1987 Copyright ©1987 by Yee, Shirley Jo-ann. All rights reserved. UMI 300N. ZeebRd. Ann Aibor, MI 48106 BLACK WOMEN ABOLITIONISTS: A STUDY OF GENDER AND RACE IN THE AMERICAN ANTISLAVERY MOVEMENT, 1828-1860 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Shirley Jo-ann Yee, A.B., M.A * * * * * The Ohio State University 1987 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Dr. -

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level Corresponding Type Chinese Court Region Court Name Administrative Name Code Code Area Supreme People’s Court 最高人民法院 最高法 Higher People's Court of 北京市高级人民 Beijing 京 110000 1 Beijing Municipality 法院 Municipality No. 1 Intermediate People's 北京市第一中级 京 01 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Shijingshan Shijingshan District People’s 北京市石景山区 京 0107 110107 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Haidian District of Haidian District People’s 北京市海淀区人 京 0108 110108 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Mentougou Mentougou District People’s 北京市门头沟区 京 0109 110109 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Changping Changping District People’s 北京市昌平区人 京 0114 110114 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Yanqing County People’s 延庆县人民法院 京 0229 110229 Yanqing County 1 Court No. 2 Intermediate People's 北京市第二中级 京 02 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Dongcheng Dongcheng District People’s 北京市东城区人 京 0101 110101 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Xicheng District Xicheng District People’s 北京市西城区人 京 0102 110102 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Fengtai District of Fengtai District People’s 北京市丰台区人 京 0106 110106 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality 1 Fangshan District Fangshan District People’s 北京市房山区人 京 0111 110111 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Daxing District of Daxing District People’s 北京市大兴区人 京 0115 -

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow At

on fellow ous L g ulletinH e Volume No. A Newsletter of the Friends of the Longfellow House and the National Park Service December pecial nniversary ssue House SelectedB As Part of Underground Railroad Network to Freedom S Henry WadsworthA LongfellowI he Longfellow National Historic Site apply for grants dedicated to Underground Turns 200 Thas been awarded status as a research Railroad preservation and research. ebruary , , marks the th facility with the Na- This new national Fanniversary of the birth of America’s tional Park Service’s Network also seeks first renowned poet, Henry Wadsworth Underground Railroad to foster communi- Longfellow. Throughout the coming year, Network to Freedom cation between re- Longfellow NHS, Harvard University, (NTF) program. This searchers and inter- Mount Auburn Cemetery, and the Maine program serves to coor- ested parties, and to Historical Society will collaborate on dinate preservation and help develop state- exhibits and events to observe the occa- education efforts na- wide organizations sion. (See related articles on page .) tionwide and link a for preserving and On February the Longfellow House multitude of historic sites, museums, and researching Underground Railroad sites. and Mount Auburn Cemetery will hold interpretive programs connected to various Robert Fudge, the Chief of Interpreta- their annual birthday celebration, for the facets of the Underground Railroad. tion and Education for the Northeast first time with the theme of Henry Long- This honor will allow the LNHS to dis- Region of the NPS, announced the selec- fellow’s connections to abolitionism. Both play the Network sign with its logo, receive tion of the Longfellow NHS for the Un- historic places will announce their new technical assistance, and participate in pro- derground Railroad Network to Freedom status as part of the NTF. -

Longfellow House's Brazilian Connection

on fellow ous L g ulletinH e Volume 4 No. 2 A Newsletter of the Friends of the Longfellow House and the National Park Service December 2000 The Emperor and the Poet: LongfellowB House’s Brazilian Connection t Brazil’s Independence Day celebra- Ambassador Costa went on to cite Dom Using Longfellow’s published letters Ation on September 7, 2000, Ambas- Pedro II‘s long correspondence with and the House archives, Jim Shea sador Mauricio Eduardo Cortes Costa, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow confirmed that on June 10, 1876 Consul General of Brazil in Boston, and his visit to the poet’s Dom Pedro II dined with bestowed upon Boston’s Mayor Thomas house in 1876. Henry W. Longfellow and Menino the “Medal Order of the South- This story has recently friends at what was then ern Cross, Rank of Commander.” The been pieced together known as Craigie House. medal was created by Brazil’s first emperor, through a collaboration In his journal Longfel- Dom Pedro I, in 1822, as he wrote, to “ac- between members of the low wrote: “Dom Pedro knowledge the relevant services rendered to National Park Service II, Emperor of Brazil, the empire by my most loyal subjects, civil and the Brazilian Con- dined with us. The servants, and foreign dignitaries, and as a sulate. In August Mar- other guests were Ralph token of my highest esteem.” cilio Farias, Cultural Waldo Emerson, Oliver In his address at the ceremony at Boston Affairs Advisor at the Wendell Holmes, Louis City Hall, the Ambassador spoke of the Brazilian Consulate in Agassiz, and Thomas Gold ties between Brazil and the U.S., particu- Boston, called Site Manager Appleton. -

China's E-Tail Revolution: Online Shopping As a Catalyst for Growth

McKinsey Global Institute McKinsey Global Institute China’s e-tail revolution: Online e-tail revolution: shoppingChina’s as a catalyst for growth March 2013 China’s e-tail revolution: Online shopping as a catalyst for growth The McKinsey Global Institute The McKinsey Global Institute (MGI), the business and economics research arm of McKinsey & Company, was established in 1990 to develop a deeper understanding of the evolving global economy. Our goal is to provide leaders in the commercial, public, and social sectors with the facts and insights on which to base management and policy decisions. MGI research combines the disciplines of economics and management, employing the analytical tools of economics with the insights of business leaders. Our “micro-to-macro” methodology examines microeconomic industry trends to better understand the broad macroeconomic forces affecting business strategy and public policy. MGI’s in-depth reports have covered more than 20 countries and 30 industries. Current research focuses on six themes: productivity and growth; natural resources; labor markets; the evolution of global financial markets; the economic impact of technology and innovation; and urbanization. Recent reports have assessed job creation, resource productivity, cities of the future, the economic impact of the Internet, and the future of manufacturing. MGI is led by two McKinsey & Company directors: Richard Dobbs and James Manyika. Michael Chui, Susan Lund, and Jaana Remes serve as MGI principals. Project teams are led by the MGI principals and a group of senior fellows, and include consultants from McKinsey & Company’s offices around the world. These teams draw on McKinsey & Company’s global network of partners and industry and management experts. -

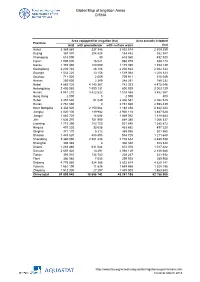

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA Area equipped for irrigation (ha) Area actually irrigated Province total with groundwater with surface water (ha) Anhui 3 369 860 337 346 3 032 514 2 309 259 Beijing 367 870 204 428 163 442 352 387 Chongqing 618 090 30 618 060 432 520 Fujian 1 005 000 16 021 988 979 938 174 Gansu 1 355 480 180 090 1 175 390 1 153 139 Guangdong 2 230 740 28 106 2 202 634 2 042 344 Guangxi 1 532 220 13 156 1 519 064 1 208 323 Guizhou 711 920 2 009 709 911 515 049 Hainan 250 600 2 349 248 251 189 232 Hebei 4 885 720 4 143 367 742 353 4 475 046 Heilongjiang 2 400 060 1 599 131 800 929 2 003 129 Henan 4 941 210 3 422 622 1 518 588 3 862 567 Hong Kong 2 000 0 2 000 800 Hubei 2 457 630 51 049 2 406 581 2 082 525 Hunan 2 761 660 0 2 761 660 2 598 439 Inner Mongolia 3 332 520 2 150 064 1 182 456 2 842 223 Jiangsu 4 020 100 119 982 3 900 118 3 487 628 Jiangxi 1 883 720 14 688 1 869 032 1 818 684 Jilin 1 636 370 751 990 884 380 1 066 337 Liaoning 1 715 390 783 750 931 640 1 385 872 Ningxia 497 220 33 538 463 682 497 220 Qinghai 371 170 5 212 365 958 301 560 Shaanxi 1 443 620 488 895 954 725 1 211 648 Shandong 5 360 090 2 581 448 2 778 642 4 485 538 Shanghai 308 340 0 308 340 308 340 Shanxi 1 283 460 611 084 672 376 1 017 422 Sichuan 2 607 420 13 291 2 594 129 2 140 680 Tianjin 393 010 134 743 258 267 321 932 Tibet 306 980 7 055 299 925 289 908 Xinjiang 4 776 980 924 366 3 852 614 4 629 141 Yunnan 1 561 190 11 635 1 549 555 1 328 186 Zhejiang 1 512 300 27 297 1 485 003 1 463 653 China total 61 899 940 18 658 742 43 241 198 52 -

BOOKS" to 9840398093

PRICE OF THIS BOOK is Rs.350 PDF COPY IS Rs.200 For Details, Whatsapp "BOOKS" to 9840398093 RADIAN IAS ACADEMY (CHENNAI - 9840400825 MADURAI - 9840398093) www.radianiasacademy.org -3- PART-C 9. Match the following Folk Arts with the Indian AUTHORS AND THEIR LITERARY WORKS State / Country 10. Match the Author with the Relevant 1.Match the Poems with the Poets Title/Character A Psalm of Life - Be the Best - The cry of the children - 11. Match the Characters with Relevant Story Title The Piano – Manliness Going for water – Earth -The Apology - Be Glad your Nose is on your face - The The Selfish Giant - How the camel got its hump - The Lottery ticket - The Last Leaf - Two friends – Refugee - Flying Wonder -Is Life But a Dream - Be the Best - O Open window – Reflowering - The Necklace Holiday captain My Captain - Snake - Punishment in Kindergarten -Where the Mind is Without fear - The Man 12. About the Poets Rabindranath Tagore - Henry Wordsworth Longfellow - He Killed - Nine Gold Medals Anne Louisa Walker -V K Gokak - Walt Whitman - 2.Which Nationality the story belongs to? Douglas Malloch The selfish Giant - The Lottery Ticket - The Last Leaf - How the Camel got its Hump - Two Friends – Refugee - 13. About the Dramatists William Shakespeare - Thomas Hardy The Open Window 14. Mention the Poem in which these lines occur 3.Identify the Author with the short story The selfish Giant - The Lottery Ticket - The Last Leaf - Granny, Granny, please comb My Hair - With a friend - To cook and Eat - To India – My Native Land - A tiger in How the Camel got its Hump - Two Friends – Refugee - the Zoo - No men are foreign – Laugh and be Merry – The Open Window - A Man who Had no Eyes - The The Apology - The Flying Wonder Tears of the Desert – Sam The Piano - The face of 15. -

Authors and Friends

Authors and Friends Annie Fields The Project Gutenberg EBook of Authors and Friends, by Annie Fields Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: Authors and Friends Author: Annie Fields Release Date: August, 2005 [EBook #8777] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on August 12, 2003] Edition: 10 Language: English Character set encoding: ISO Latin-1 *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK AUTHORS AND FRIENDS *** Produced by Tiffany Vergon, Patricia Ehler and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team. AUTHORS AND FRIENDS by ANNIE FIELDS '"The Company of the Leaf" wore laurel chaplets "whose lusty green may not appaired be." They represent the brave and steadfast of all ages, the great knights and champions, the constant lovers and pure women of past and present times.' Keping beautie fresh and greene For there nis storme that ne may hem deface.