Maps, Mission, Memory and Mizo Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nandini Sundar

Interning Insurgent Populations: the buried histories of Indian Democracy Nandini Sundar Darzo (Mizoram) was one of the richest villages I have ever seen in this part of the world. There were ample stores of paddy, fowl and pigs. The villagers appeared well-fed and well-clad and most of them had some money in cash. We arrived in the village about ten in the morning. My orders were to get the villagers to collect whatever moveable property they could, and to set their own village on fire at seven in the evening. I also had orders to burn all the paddy and other grain that could not be carried away by the villagers to the new centre so as to keep food out of reach of the insurgents…. I somehow couldn’t do it. I called the Village Council President and told him that in three hours his men could hide all the excess paddy and other food grains in the caves and return for it after a few days under army escort. They concealed everything most efficiently. Night fell, and I had to persuade the villagers to come out and set fire to their homes. Nobody came out. Then I had to order my soldiers to enter every house and force the people out. Every man, woman and child who could walk came out with as much of his or her belongings and food as they could. But they wouldn’t set fire to their homes. Ultimately, I lit a torch myself and set fire to one of the houses. -

Vol III Issue I June2017

Vol III Issue 1 June 2017 ISSN 2395-7352 MIZORAM UNIVERSITY JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES & SOCIAL SCIENCES (A National Refereed Bi-Annual Journal) MIZORAM UNIVERSITY NAAC Accredited Grade ‘A’ (2014) (A CENTRAL UNIVERSITY) TANHRIL, AIZAWL – 796004 MIZORAM, INDIA i . ii Vol III Issue 1 June 2017 ISSN 2395-7352 MIZORAM UNIVERSITY JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES & SOCIAL SCIENCES (A National Refereed Bi-Annual Journal) Chief Editor Prof. Margaret Ch. Zama Editor Prof. J. Doungel iii Patron : Prof. Lianzela, Vice Chancellor, Mizoram University Advisor : Mr. C. Zothankhuma, IDAS, Registrar, Mizoram University Editorial Board Prof. Margaret Ch. Zama, Dept. of English, Chief Editor Prof. Srinibas Pathi, Dept. of Public Administration, Member Prof. NVR Jyoti Kumar, Dept. of Commerce, Member Prof. Lalhmasai Chuaungo, Dept. of Education, Member Prof. Sanjay Kumar, Dept. of Hindi, Member Prof. J. Doungel, Dept. of Political Science, Member Dr. V. Ratnamala, Dept. of Jour & Mass Communication, Member Dr. Hmingthanzuali, Dept. of History & Ethnography, Member Mr. Lalsangzuala, Dept. of Mizo, Member National Advisory Board Prof. Sukadev Nanda, Former Vice Chancellor of FM University, Bhubaneswar Prof. K. Rama Mohana Rao, Andhra University, Visakhapatnam Prof. K. C. Baral, Director, EFLU, Shillong Prof. Arun Hota, West Bengal State University, Barasat, West Bengal Dr. Sunil Behari Mohanty, Editor, Journal of AIAER, Puducherry Prof. Joy. L. Pachuau, JNU, New Delhi Prof. G. Ravindran, University of Madras, Chennai Prof. Ksh. Bimola Devi, Manipur University, Imphal iv CONTENTS From the Desk of the Chief Editor vii Conceptualizing Traditions and Traditional Institutions in Northeast India 1 - T.T. Haokip Electoral Reform: A Lesson from Mizoram People Forum (MPF) 11 - Joseph C. -

Ethnobiology in Mizoram State: Folklore Medico-Zoology

Bull.Ind.lnst.Hist.Med. Vol. XXIX - 1999 pp /23 tc 148 ETHNOBIOLOGY IN MIZORAM STATE: FOLKLORE MEDICO-ZOOLOGY H.LALRAMNGHINGLOVA * ABSTRACT Studies in cthnobotany and ethnozoology under the umbrella of Ethnobiology seem imbalanced in the sense that enormous publications have accumulated in case of the former but only little information has been disseminated in case of the latter. While 7500 wild plant species are known to be used by tribals in medicine, only 76 species of animals have been shown as medicinal resources (Anonymous, 1994). The present paper is the first-hand information of folklore medicine from animals in Mizoram. The animals enumerated comprise 01'25 vertebrates and 31 invertebrates and arc used for treatment of over 40 kinds of diseases or ailments, including jaundice, tuberculosis, hepatitis, cancer, asthma and veterinary disease. The author, however, does not recommend destruction of wild animals, he it for food or medicine. Keywords: Folklore medicine, ethnozoology, wildlife, conservation, Mizoram. Introduction operation correlate with their customs and Mizoram is the last frontier of the ceremonies. One of the most important Hirnalyan ranges in the North-East India feasts a Lushai can perform is called and flanked by Bangladesh in the west, 'Khuangchawi' which involved a great deal Myanmar in the east and south, and Assam of money that only the Chiefs or a few we//- in the north. It has a total geographical area to-do people could perform (Parry, 1928). of 21,081 Km ' with a population of A man who performed such ceremony was 6,89,756 persons (census 19(1) and stood called 'Thangchhuah '. -

The “Gospel” of Cultural Sustainability: Missiological Insights

The “Gospel” of Cultural Sustainability: Missiological Insights Anna Ralph Master’s Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at Goucher College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Cultural Sustainability Goucher College—Towson, Maryland May 2013 Advisory Committee Amy Skillman, M.A. (Advisor) Rory Turner, PhD Richard Showalter, DMin Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... iii Chapter One—The Conceptual Groundwork ................................................................................. 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 Definition—“Missiology” .................................................................................................... 4 Definition—“Cultural Sustainability” .................................................................................. 5 Rationale ............................................................................................................................. 7 Methodology ..................................................................................................................... 11 Review of Literature—Cultural Sustainability................................................................... 12 Review of Literature—Missiology .................................................................................... -

Cultural Factors of Christianizing the Erstwhile Lushai Hills (1890-1940)

Mizoram University Journal of Humanities & Social Sciences (A Bi-Annual Refereed Journal) Vol IV Issue 2, December 2018 ISSN: 2395-7352 eISSN:2581-6780 Cultural Factors of Christianizing the erstwhile Lushai Hills (1890-1940) Zadingluaia Chinzah* Abstract Alexandrapore incident became a turning point in the history of the erstwhile Lushai Hills inhabited by simple hill people, living an egalitarian and communitarian life. The result of the encounter between two diverse and dissimilar cultures that were contrary to their form of living and thinking in every way imaginable resulted in the political annexation of the erstwhile Lushai Hills by the British colonial power,which was soon followed by the arrival of missionaries. In consolidating their hegemony and imperial designs, the missionaries were tools through which the hill tribes were to be pacified from raiding British territories. In the long run, this encounter resulted in the emergence and escalation of Christianity in such a massive scale that the hill tribes with their primal religious practices were converted into a westernised reli- gion. The paper problematizes claims for factors that led to the rise of Christianity by various Mizo Church historians, inclusive of the early generations and the emerging church historians. Most of these historians believed that waves of Revivalism was the major factor in Christianizing the erstwhile Lushai Hills though their perspectives or approach to their presumptions are different. Hence, the paper hypothesizes that cultural factors were integral to the rise and growth of Christianity in the erstwhile Lushai Hills during 1890-1940 as against the claims made before. Keywords : ‘Cultural Factors of Conversion,’ Tlawmngaihna, Thangchhuah, Pialral, Revivals. -

Mizo Subject Under Cbcs Courses (Choice Based Credit System) for Undergraduate Courses

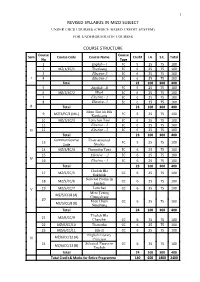

1 REVISED SYLLABUS IN MIZO SUBJECT UNDER CBCS COURSES (CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM) FOR UNDERGRADUATE COURSES COURSE STRUCTURE Course Course Sem Course Code Course Name Credit I.A. S.E. Total No Type 1 English – I FC 5 25 75 100 2 MZ/1/EC/1 Thutluang EC 6 25 75 100 3 Elective-2 EC 6 25 75 100 I 4 Elective-3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 5 English - II FC 5 25 75 100 6 MZ/2/EC/2 Hla-I EC 6 25 75 100 7 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 8 Elective- 3 EC 6 25 75 100 II Total 23 100 300 400 Mizo Thu leh Hla 9 MZ/3/FC/3 (MIL) FC 5 25 75 100 Kamkeuna 10 MZ/3/EC/3 Lemchan Tawi EC 6 25 75 100 11 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 III 12 Elective - 3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 Common Course Environmental 13 FC 5 25 75 100 Code Studies 14 MZ/4/EC/4 Thawnthu Tawi EC 6 25 75 100 15 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 IV 16 Elective - 3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 Thu leh Hla 17 MZ/5/CC/5 CC 6 25 75 100 Sukthlek Selected Poems in 18 MZ/5/CC/6 CC 6 25 75 100 English V 19 MZ/5/CC/7 Lemchan CC 6 25 75 100 Mizo |awng MZ/5/CC/8 (A) Chungchang 20 Mizo Hnam CC 6 25 75 100 MZ/5/CC/8 (B) Nunphung Total 24 100 300 400 Thu leh Hla 21 MZ/6/CC/9 Chanchin CC 6 25 75 100 22 MZ/6/CC/10 Thawnthu CC 6 25 75 100 23 MZ/6/CC/11 Hla-II CC 6 25 75 100 English Literary MZ/6/CC/12 (A) VI Criticism 24 Selected Essays in CC 6 25 75 100 MZ/6/CC/12 (B) English Total 24 100 300 400 Total Credit & Marks for Entire Programme 140 600 1800 2400 2 DETAILED COURSE CONTENTS SEMESTER-I Course : MZ/1/EC/1 - Thutluang ( Prose & Essays) Unit I : 1) Pu Hanga Leilet Veng - C. -

Eighth Legislative Assembly of Mizoram (Fourth Session)

1 EIGHTH LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF MIZORAM (FOURTH SESSION) LIST OF BUSINESS FOR FIRST SITTING ON TUESDAY, THE 19th NOVEMBER, 2019 (Time 10:30 A.M. to 1:00 P.M. and 2:00 P.M. to 4:00 P.M.) OBITUARY 1. PU ZORAMTHANGA, hon. Chief Minister to make Obituary reference on the demise of Pu Thankima, former Member of Mizoram Legislative Assembly. QUESTIONS 2. Questions entered in separate list to be asked and oral answers given. ANNOUNCEMENT 3. THE SPEAKER to announce Panel of Chairmen. LAYING OF PAPERS 4. Dr. K. PACHHUNGA, to lay on the Table of the House a copy of Statement of Action Taken on the further recommendation of Committee on Estimates contained in the First Report of 2019 relating to State Investment Programme Management Implementation Unit (SIPMIU) under Urban Development & Poverty Alleviation Department Government of Mizoram. 5. Dr. ZR. THIAMSANGA, to lay on the Table of the House a a copy Statement of Actions Taken by the Government against further recommendations contained in the Third Report, 2019 of Subject Committee-III relating to HIV/AIDS under Health & Family Welfare Department. PRESENTATION OF REPORTS 6. THE SPEAKER to present to the House the Third Report of Business Advisory Committee. 7. PU LALDUHOMA to present to the House the following Reports of Public Accounts Committee : 2 i) First Report on the Report of Comptroller & Auditor General of India for the year 2011-12, 2012-13, 2013-14, 2014-15 and 2015-16 relating to Taxation Department. ii) Second Report on the Report of Comptroller & Auditor General of India for the year 2014-15 and 2015-16 relating to Food, Civil Supplies and Consumer Affairs Department. -

Synod 2017 Bulletin 3

INKHAWMPUI VAWI 94-NA December 5 - 10, 2017 Bungkawn Pastor Bial : Bungkawn Kohhran Biak In INKHAWMPUI CHANCHINBU CHHUAH THUMNA DECEMBER 10, 2017 (PATHIANNI) LAWMTHU SAWINA SYNOD INKHAWMPUI VAWI 94-NA Synod Vawi 94-na chu tluang takin kan TLUANG TAKA HMAN MEK ZEL A NI lo zo dawn ta a. Inkhawmpui tluang taka min hruaitu Pathian hnenah te, Bungkawn Synod Inkhawmpui Vawi 94-na chu tluang taka hman mek zel a ni. A thlengtu Pastor Bial chhunga Kohhran hrang Bungkawn Pastor Bialin nghakhlel taka kan lo thlir chu a bul kan tan dawn chauh hrangte chungah te, Sub-Committtee emaw kan tih laiin zaninah a lo tiak dawn ta reng mai. Hei hi Palai zawng zawngte hrang hrangte chungah leh mimal chanvo kan mangthana che u ni nghal mai se, mahni khua leh veng lam kan pan hunah dam neitu kohhran member-te chungah taka in haw a, tluang taka rawng in bawl zel theih nan duhsakna sang ber kan hlan a lawmthu kan sawi a. Synod Inkhawmpui che u. Tin, 2018 Synod Inkhawmpui Electric Veng Biak Ina neih tur atan Electric kan thlenna kawnga kan mamawh phal Veng Pastor Bial pawh duhsakna sang ber kan hlan nghal bawk a ni. taka min hmantirtu hrang hrangte hnenah Inkhawmpui rorel tluang taka neih chu dar 1:30 ah tan a ni dawn a. lawmthu kan sawi bawk a, chungte chu - niin nimin, Inrinni khan rorel zawh hman Chawhnu inkhawmah Lalpa Zanriah 1) Mizoram State Sports Council a nih loh avangin nizan inkhawm ban Sakramen kilho a ni ang a. He hunah - Mattress 100 nos. -

TJ:Te Mizoram Ga%Ette Pu�Lished by Authority

Regd. Ne. NE 907 i TJ:te Mizoram Ga%ette Pu�lished by Authority __ r T , , I.: ..... ',.,ily. 2). { DH, . Bhadr. 4, S.E. 1916,'· issue No. 34 ar Government of Mizonm , Part I and A"t>oinlments, P08tings, Trznsfers. Powers ot�cr ,Noticesand Orcers. (ORDERS BY THE GOVERNOR) NOTIFICATIONS ,. '� No. A. 23031/2/84-IPR, the 26th August, 1994. !fhe Governor of ·Mizoram is . ...pleased to fix the final inteese-seniority of Assistant Public R,olations Officer.' "'" under Information & Public Relations Depe{lment as allow,,,b.olow. SI. No. in onder Name of Seniority. " 1. ZothankuogJ i; 2. Lallian.x?!'. 3. Lalnu . 4. Laitbangmal'lia Y4llldir 5. R. Vanhnuaithauga 6. David Laltbangliana 7. Lalsiama Famkwl 8. Sangkamlova . , " , .- • No. F. 14011/I/90-IPR, the 25th August, 1994. 10 puisuance <If .the provision . contained in the Mizoram Press Representative AccreditaMQ.\1.. • .\Wlea. 1984, the Registration of Books A<;t. 1967 and the Working Journalist ,..!!, other News papers Employees (condition of service) and M���PrO�lon Aot 1955, the Governor of Mizoram is pleased g renew the t!':flll O;t'. .th�·� Aocredi ted Journalist for another peri<idof one year as ahown bel<l,\'I'. d. R-34/94 2 SL. NAME OF EDITORS NEWSPAPERS No. REPRESENTED 1. Pu Lalbiakthanga Pachaan Zoram Tlangau 2. Pu�apdanga Vanglaini 3.· Pu Lalrinawma Tawrhbawm 4. Pu C. Lalzamlova Chhawrpial 5. Pu J. Lalthangliana Mizo Arsi 6. Pu R.L. Rina Hunthar . 7. Pu Robert La\chhuana . Romei 8. Pu C. Lalkhawliana Highlander 9. !,u D.R. Zirliana Mizo Aw 10. Pu Runbika Zoeng/Hnehtu 11. -

Rih Dil Titi

Rih Dil Titi “There! That’s the lake!” exclaimed my mother, pointing her finger towards the mirroring body of water laid flat across the plains of Tiau valley. It was an uncharacteristic of her to make any display of excitement. It had been an awfully long drive and we were all weary of the dusty Mizoram roads. We were returning from a friend’s wedding in Sialhawk, a small sleepy village in the east not far from Champhai, the district capital bordering Myanmar. And in the excitement of our celebration of young love, tradition and inspired speeches of eternal bonds, we had decided to take the scenic route to Rihkhawdar before returning back to Keitum. Yes, we were on our way to see Rih dil- the lake that symbolised love, life, death and the afterlife. I was excited because the place held within it the secrets and legends of everything that would meet a young man’s fancy. The scenic part was definitely accurate, but truth be told we were miles out of our way home and we had underestimated the distance; it appeared I had also overestimated my zeal for long drives. We stopped at Champhai, which is one of the few places in Mizoram where we find plains which are used for rice cultivation. The place is known to be hammered down by Chhura, a mythical figure in the Mizo folklore who is often attributed to many of the unnatural places found in Mizoram. We drove in excitement at the only long straight road sandwiched between the rice fields before ascending up again at the steep and winding mountain roads. -

Download This PDF File

The International Journal Of Humanities & Social Studies (ISSN 2321 - 9203) www.theijhss.com THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES & SOCIAL STUDIES The Darlong Folk Literature: A Study on Deification of Characters in the Oral Narratives of the Darlong People during the Pre-Christianisation Period Benjamina Darlong Research Scholar, Department of English, Tripura University Abstract: The objective of the paper is to study the paradigm of canonization in the oral narratives of the Darlong community aiming not at identifying the pattern. The materials of the article are primarily based on the oral tradition and orature collected among the community men and women in addition to the few documentations made in vernacular by different literary interested personage. The article trace diverge characterization as delineated in the folk narratives of the Darlong. The momentum of the canonization culminates in when deeds of the hero that are elements of crime in today’s perspective are hailed by the people thereby capturing many of their old practices. In the mean time, certain characters are exalted to the state of deity eventually perpetuating them. 1. Introduction to the Study The Darlong of Tripura belonged to one among the many communities of the Kuki-Chin group who are also known under the nomenclature of ‘Zo-Hnathla1’ or ‘Zo mi’. “The Kukis are one of the autochthonous tribes of Tripura. According to the 1971 census, the Kuki population in Tripura was only 7,775 persons. They are tenth in the numerical position among the 19 scheduled Tribes of Tripura. They do not call themselves as Kukis but Hre-em. -

A Concept for Union and an Identity Marker for Mizo Christians

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Journals of Faculty of Orthodox Theology, Babes-Bolyai University (Romania) SUBBTO 63, no. 2 (2018): 75-90 DOI:10.24193/subbto.2018.2.06 II. HISTORICAL THEOLOGY HEAVENLY CITIZENSHIP: A CONCEPT FOR UNION AND AN IDENTITY MARKER FOR MIZO CHRISTIANS MARINA NGURSANGZELI BEHERA* ABSTRACT. Paul, as it is well known, was a citizen of the Roman Empire and he wrote these words about citizenship to a young congregation in a Hellenistic city. The Greek word „in Philippians 3:20” he uses here is translated differently as “conservation” (KJV), as “home” and as “citizenship” in the New American Standard (NAS) translation. So, Christian citizenship is in heaven - not on earth. It is from there Christians expect their Lord and savior to come. Yet, while living on earth and waiting until He comes and while being part of the larger human community each and every one is a member of political unit, a nation or a state or a tribe. The knowledge of the heavenly citizenship gives Christians an indication where to hope for true citizenship and gives at the same time a clear indication to distinguish between “heavenly” affairs and their allegiance to worldly powers on earth. During the initial period of the history of Christianity in Mizoram in order to differentiate one’s new identity was the conviction and the declaration that one is now Pathian mi (God’s people) and vanram mi (heavenly citizen). This significant concept and understanding of what it means for the Mizo to be Christian is reflected prominently in Mizo indigenous hymns and gospel songs as well as in the preaching of the Gospel, where it is declared that one is no longer a citizen of this “earthly world” (he lei ram mi), but of the “heavenly world” (van ram mi).