Shakespeare in the Classroom: to Be Or Not to Be? Sandeep Purewal 1,2 *

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gopher Tortoises on the Move to Tallahassee Ing Range and a Change to a Development Agree- by SCOTT DRESSEL What They Do

PAGE B1 ▲ Chamber crowns 2014 Miss and Jr. Miss Avon Park A3 EWS UN Dragons and ▲ NHighlands County’s Hometown Newspaper-S Since 1927 75¢ Devils send large group TV weatherman fl ies in to remind through to students to ‘choose sunny’ A2 regionals A11 www.newssun.com Sunday, April 13, 2014 County to Legislators talk military support air zones, SLOW & city garbage half-cent BY BARRY FOSTER school tax News-Sun Correspondent STEADY SEBRING — Revenue at Howerton, Shoop the county’s landfi ll, pro- take sales tax pitch posed Military Airport Zones around the Bomb- Gopher tortoises on the move to Tallahassee ing Range and a change to a development agree- BY SCOTT DRESSEL what they do. They’re cold-blooded, so they BY PHIL ATTINGER ment with a local RV Editor all move,” Florida Fish and Wildlife Conser- Staff Writer park are among the items vation Commission (FWC) spokesman Gary up for discussion Tues- hen the weather heats up for spring, Morse said. SEBRING — School board day morning at the High- it puts a series of things in motion. A basic need drives the tortoises to venture members had positive news from lands County Commission WThe most noticeable, of course, is the out — food. a recent trip to Tallahassee to talk meeting. snowbirds starting to make their way back “Tortoises stay under ground in their bur- up the district’s plan for a half- First on the agenda will up north. rows when its cold out and they come out cent sales tax referendum. be a board discussion of But closer to the ground, and at a much looking for food when it warms up,” Morse Board members Donna How- published reports regard- slower pace, there is another migration of said. -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

BUSINESS Brittain Stone EDC Won’T Release Pier Study Long on Talent by Lisa J

SATURDAY • MAY 22, 2004 Including Carroll Gardens-Cobble Hill Paper, Downtown News, DUMBO Paper and Fort Greene-Clinton Hill Paper Brooklyn’s REAL newspapers Published every Saturday by Brooklyn Paper Publications Inc, 55 Washington Street, Suite 624, Brooklyn NY 11201. Phone 718-834-9350 • www.BrooklynPapers.com • © 2004 Brooklyn Paper Publications • 20 pages including GO BROOKLYN • Vol. 27, No. 20 BWN • Saturday, May 22, 2004 • FREE CITY TO PUBLIC ON B’KLYN WATERFRONT: NONE OF YOUR THIS WEEKEND BUSINESS Brittain Stone EDC won’t release pier study Long on talent By Lisa J. Curtis and Urban Divers. Michael Sherman, an EDC spokesman, told GO Brooklyn editor An exhibit of a wide variety of artworks by EXCLUSIVE The Brooklyn Papers, “There are no such plans hundreds of artists, the Brooklyn Waterfront at the moment,” when asked about the study’s re- NOT JUST NETS Critically acclaimed talents and youth Artists Coalition Pier Show 12 continues, and lease. THE NEW BROOKLYN groups alike will strut their stuff on the will be on display in the warehouse at 499 Van By Deborah Kolben “It was always just going to be for our internal Beard Street Pier in Red Hook this Sat- Brunt St. from noon to 6 pm. The Brooklyn Papers urday, May 22, as part of the 10th annual The Arts Festival events take place from 1 pm use,” he said, adding that an executive summary Hamilton, Rabinovitz & Alschuler, saying they Red Hook residents and merchants who or “highlights” of the study might be released “at Red Hook Waterfront Arts Festival. to 5 pm at the Beard Street Pier, Van Brunt ignored community input throughout the process Among the troupes that will take the stage are Street at the Red Hook Channel, and the per- have been eagerly awaiting the results of a some point.” and came in with a preconceived agenda to major city-sponsored study on the future of “Our thinking is that we’re just using the in- the Urban Bush Women, Dance Wave Kids Com- formances are free. -

Trends in Teen Sex Are Changing, but Are Minnesota's Romeo and Juliet Laws? Jana L

William Mitchell Law Review Volume 39 | Issue 5 Article 7 2013 Trends in Teen Sex Are Changing, but Are Minnesota's Romeo and Juliet Laws? Jana L. Kern Follow this and additional works at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr Recommended Citation Kern, Jana L. (2013) "Trends in Teen Sex Are Changing, but Are Minnesota's Romeo and Juliet Laws?," William Mitchell Law Review: Vol. 39: Iss. 5, Article 7. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr/vol39/iss5/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in William Mitchell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law Kern: Trends in Teen Sex Are Changing, but Are Minnesota's Romeo and Ju TRENDS IN TEEN SEX ARE CHANGING, BUT ARE MINNESOTA’S ROMEO AND JULIET LAWS? Jana L. Kern† I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................... 1607 II. PURPOSE OF THE LAWS AND THE EXTENT OF PROTECTION 1608 III. AGE OF CONSENT ................................................................. 1609 IV. TYPES OF PROTECTION FOR TEENS FROM STATUTORY RAPE LAWS .................................................................................... 1611 A. Age-Gap Provisions ......................................................... 1611 B. Romeo and Juliet Clauses ................................................ 1613 C. Minority State Law -

Emo in a Musical

e-mo [i mõ] An entire subculture of people (usually angsty teens) with a fake personality. TAGLINE: Finally a musical for those who don’t like musicals. LOGLINE: A sullen high-school student whose life is defined By what he hates finds love with a Blindly optimistic Christian girl, much to the annoyance of his angst-filled Band mates and her evangelistic Brethren. SPECIFICATIONS: Type: Feature Film Genre: High School Musical Elevated By: Coming of Age, Romance, Buddy Antics, Turf War and Satire Tone: Irreverent Themes: Extremism, Difference, Conformity, Young Love Running Time: 94 mins Audience: Primary 15-24, gender neutral Secondary 24-35 female skewed Film References: Election, Mean Girls, Cry Baby, Pitch Perfect. Comp’s: Easy A, Warm Bodies, If I Stay, Saved. Writer/Director: Neil Triffett Producer: Lee Matthews Exec Producers: Yael Bergman, Jonathan Page, Shaun Miller SongBook: Neil Triffett in collaBoration Language: English Format: Digital HD/DCP Aspect Ratio: 2.39/1 Premiering: MIFF 2016 Copyright: Matthewswood Pty Ltd. Developed and Produced with the support of Screen Australia, Film Victoria and MIFF Premiere Fund. Page 1 © 2016 Matthewswood Pty Ltd SHORT SYNOPSIS: Ethan is an Emo who has just Been expelled from his private-school after attempting suicide in the courtyard. On his first day at his new school – the dilapidated Seymour High - he meets Trinity, a beautiful (but totally naive) Christian girl who is desperate to convert him to Jesus. But joining the Christian evangelists is the last thing on Ethan’s mind. What he really wants is to join the school alternative rock band, ‘Worst Day Ever’ and to be part of the Emo clique, led by the enigmatic and dangerous, Bradley. -

The Relevance of Twelfth Night for Adolescents

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Student Works 2012-12-13 The Relevance of Twelfth Night for Adolescents Sarah Monson [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/studentpub Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Intensive reading, discussion, and (in some sections) viewing of plays from the comedy, tragedy, romance, and history genres. BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Monson, Sarah, "The Relevance of Twelfth Night for Adolescents" (2012). Student Works. 104. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/studentpub/104 This Class Project or Paper is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Works by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Monson 1 Sarah Monson Dr. Burton English 382 December 14, 2012 “Not yet old enough for a man, nor young enough for a boy; as a squash is before „tis a peascod, or a codling when „tis almost an apple: „tis with him in standing water, between boy and man.” (Twelfth Night 1.5.162-165) The Relevance of Twelfth Night for Adolescents For years, Romeo and Juliet has been the standard choice for English teachers of adolescents. However, there are different problems that can potentially arise from teaching this play. For example, the only type of romance explored in the text is forbidden young love that ends in suicide. This should not be the type of romance that young students can relate to as it is not a healthy model to follow. In a report in the Digital Journal Mullins said, “There are times when young lovers who face problems from the outside turn to suicide. -

Animation Guide

Animation Guide Summer 2017 Preface & Acknowledgements This text represents the work of a group of 28 teachers enrolled in a Media Studies course at the University of British Columbia in the summer of 2017, instructed by Dr. Rachel Ralph. The challenge for the group was to write a Media Studies text that appealed to students in a range from grades 8-12 in the school system, providing teachers with an interesting, diverse, and rich resource for use in the classroom. The individual sections can be adopted and integrated into any number of subjects or adopted as a textbook for New Media Studies in the schools. Many of the Media Study Guides span provincial curricula, exploring commonalities and differences. We acknowledge the support of family and friends and the various cultural agents and artists whose illustrations or texts were incorporated into the sections of the book. We acknowledge the work of students who contributed towards publishing this textbook. We hope you are as inspired with the insights within each section, as we were producing these, and we encourage you to continue learning about media, culture, and technology. Table of Contents Media Guide and Major Themes……………………..……….……………………..……………....Page Preface and Acknowledgments…………….………..………..………..………….………………………………2 Cars (Friendship, Community and Environment, Diversity).……..………..………………….……..……4 Finding Dory (Abilities and Disabilities, Family & Friendship, Identity) …………………….………………….…12 Inside Out (Emotions, Memories, Family, Grief/Loss) ………………………………………….………..………….…22 The Legend -

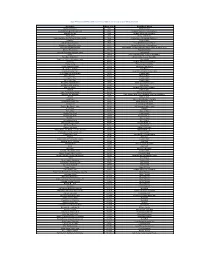

SONG CODE and Send to 4000 to Set a Song As Your Welcome Tune

Type WT<space>SONG CODE and send to 4000 to set a song as your Welcome Tune Song Name Song Code Artist/Movie/Album Aaj Apchaa Raate 5631 Anindya N Upal Ami Pathbhola Ek Pathik Esechhi 5633 Hemanta Mukherjee N Asha Bhosle Andhakarer Pare 5634 Somlata Acharyya Chowdhury Ashaa Jaoa 5635 Boney Chakravarty Auld Lang Syne And Purano Sei Diner Katha 5636 Shano Banerji N Subhajit Mukherjee Badrakto 5637 Rupam Islam Bak Bak Bakam Bakam 5638 Priya Bhattacharya N Chorus Bhalobese Diganta Diyechho 5639 Hemanta Mukherjee N Asha Bhosle Bhootader Bechitranusthan 56310 Dola Ganguli Parama Banerjee Shano Banerji N Aneek Dutta Bhooter Bhobishyot 56312 Rupankar Bagchi Bhooter Bhobishyot karaoke Track 56311 Instrumental Brishti 56313 Anjan Dutt N Somlata Acharyya Chowdhury Bum Bum Chika Bum 56315 Shamik Sinha n sumit Samaddar Bum Bum Chika Bum karaoke Track 56314 Instrumental Chalo Jai 56316 Somlata Acharyya Chowdhury Chena Chena 56317 Zubeen Garg N Anindita Chena Shona Prithibita 56318 Nachiketa Chakraborty Deep Jwele Oi Tara 56319 Asha Bhosle Dekhlam Dekhar Par 56320 Javed Ali N Anwesha Dutta Gupta Ei To Aami Club Kolkata Mix 56321 Rupam Islam Ei To Aami One 56322 Rupam Islam Ei To Aami Three 56323 Rupam Islam Ei To Aami Two 56324 Rupam Islam Ek Jhatkay Baba Ma Raji 56325 Shaan n mahalakshmi Iyer Ekali Biral Niral Shayane 56326 Asha Bhosle Ekla Anek Door 56327 Somlata Acharyya Chowdhury Gaanola 56328 Kabir Suman Hate Tomar Kaita Rekha 56329 Boney Chakravarty Jagorane Jay Bibhabori 56330 Kabir Suman Anjan Dutt N Somlata Acharyya Chowdhury Jatiswar 56361 -

Views of the Sanctity of International 5 Sovereignty Or the Right of States to Act Unilaterally, Become Known As the Assertive Multilateralists

WARS WITHOUT RISK: U.S.HUMANITARIAN INTERVENTIONS OF THE 1990S R Laurent Cousineau A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2010 Committee: Dr. Gary Hess, Advisor Dr. Neal Jesse Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Robert Buffington Dr. Stephen Ortiz ii ABSTRACT Dr. Gary Hess, Advisor Wars Without Risk is an analysis of U.S. foreign policy under George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton involving forced humanitarian military operations in Somalia and Haiti in the 1990s. The dissertation examines American post-Cold war foreign policy and the abrupt shift to involve U.S. armed forces in United Nations peacekeeping and peace enforcement operations to conduct limited humanitarian and nation-building projects. The focus of the study is on policy formulation and execution in two case studies of Somalia and Haiti. Wars Without Risk examines the fundamental flaws in the attempt to embrace assertive multilateralism (a neo-Wilsonian Progressive attempt to create world peace and stability through international force, collective security, international aid, and democratization) and to overextend the traditional democratization mandates of American foreign policy which inevitably led to failure, fraud, and waste. U.S. military might was haphazardly injected in ill-defined UN operations to save nations from themselves and to spread or “save” democracy in nations that were not strongly rooted in Western enlightenment foundations. Missions in Somalia and Haiti were launched as “feel good” humanitarian operations designed as attempts to rescue “failed states” but these emotionally- based operations had no chance of success in realistic terms because the root causes of poverty and conflict in targeted nations were too great to address through half-hearted international paternalism. -

D. W. Griffith : American Film Master by Iris Barry

D. W. Griffith : American film master By Iris Barry Author Barry, Iris, 1895-1969 Date 1940 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2993 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art D. W. GRIFFITH AMERICAN FILM MASTER BY IBIS BABBY J MrTHE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART NEW YORK MoMA 115 c.2 D. W. GRIFFITH: AMERICANFILM MASTER Shooting night scenes in the snow at Mamaroneck, New York, for way down east, 1920. D. W GRIFFITH AMERICAN FILM MASTER BY IRIS BARRY X MUSEUM OF MODERN ART FILM LIRRARY SERIES NO. 1 NEW YORK THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART /IfL &/&? US t-2-. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS TRUSTEES OF THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART The President and Trustees of the Museum of Modern Stephen C. Clark, Chairman of the Board; John Hay Art wish to thank those who have lent to the exhibition Whitney, 1st Vice-Chairman; Samuel A. Lewisohn, 2nd and, in addition, those who have generously rendered Vice-Chairman; Nelson A. Rockefeller, President; assistance: Mr. and Mrs. David Wark Griffith; Mr. W. Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Vice-President and Director; John R. Oglesby; Miss Anita Loos and Metro-Goldwyn- E. Abbott, Executive Vice-President; Mrs. John S. Mayer Studios; Mr. W illiam D. Kelly of Lowe's, In Sheppard, Treasurer; Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss, Mrs. corporated; Mr. George Freedley, Curator of the W. -

Act 1 Two Households, Both Alike in Dignity. Along the Fair

Act 1 Two households, both alike in dignity. Along the fair Saskatchewan Prairies, we lay our scene. It’s not as flat as they say, you just have to go north. But it’s in the flat south where civil blood makes civil hands unclean. From forth the horny woes of adolescence, a pair of star-crossed lovers offer up their lives. Amongst pleas, the adults have heard enough. With his death, Romeo hopes to bury the strife. A fearful passage of death-marked love and the continuance of rage – which but marked their children’s end, naught could remove. What here was missed, my toil shall strive to mend it in the impending passages. “Clean your room, Romeo!” Mother Teresa yells out. “Give me an hour…” Tiny Romeo mumbles. “Now!” Montague yells in a typical rage at Romeo’s lack of listening capabilities. I listened fine! I could hear my own heartbeat and thoughts after all… It wasn’t that Romeo didn’t listen; Romeo just listened when it made sense to listen. Midway through a video game level was not the ideal time to go and clean one’s bedroom. “Eat your supper!” Mother Teresa yells out. “But it’s gross…” Romeo says. A battle held in contention with the family over many years. Green beans were the worst. Which was weird because I liked them as a baby. But where could one put such foul offerings? I tried the top of the garbage, even the bottom. I put them in my pocket, but they ended up in washing machine. -

HOLLYWOOD's WEST: the American Frontier in Film, Television, And

o HOLLYWOOD’S WEST WEST*FrontMtr.pmd 1 8/31/05, 4:52 PM This page intentionally left blank HOLLYWOOD’S WEST The American Frontier in o Film, Television, and History EDITED BY PETER C. ROLLINS JOHN E. O’CONNOR THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY WEST*FrontMtr.pmd 3 8/31/05, 4:52 PM Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 2005 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508–4008 www.kentuckypress.com 0908070605 54321 “Challenging Legends, Complicating Border Lines: The Concept of ‘Frontera’ in John Sayles’s Lone Star” © 2005 by Kimberly Sultze. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hollywood’s West : The American frontier in film, television, and history / edited by Peter C. Rollins and John E. O'Connor. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8131-2354-2 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Western films—United States—History and criticism. 2. Western television programs—United States. I. O'Connor, John E. II. Rollins, Peter C. PN1995.9.W4A44 2005 791.436'278--dc22 2005018026 This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.