A Computational Perspective on the Romanian Dialects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Romanian Language and Its Dialects

Social Sciences ROMANIAN LANGUAGE AND ITS DIALECTS Ana-Maria DUDĂU1 ABSTRACT: THE ROMANIAN LANGUAGE, THE CONTINUANCE OF THE LATIN LANGUAGE SPOKEN IN THE EASTERN PARTS OF THE FORMER ROMAN EMPIRE, COMES WITH ITS FOUR DIALECTS: DACO- ROMANIAN, AROMANIAN, MEGLENO-ROMANIAN AND ISTRO-ROMANIAN TO COMPLETE THE EUROPEAN LINGUISTIC PALETTE. THE ROMANIAN LINGUISTS HAVE ALWAYS SHOWN A PERMANENT CONCERN FOR BOTH THE IDENTITY AND THE STATUS OF THE ROMANIAN LANGUAGE AND ITS DIALECTS, THUS SUPPORTING THE EXISTENCE OF THE ETHNIC, LINGUISTIC AND CULTURAL PARTICULARITIES OF THE MINORITIES AND REJECTING, FIRMLY, ANY ATTEMPT TO ASSIMILATE THEM BY FORCE KEYWORDS: MULTILINGUALISM, DIALECT, ASSIMILATION, OFFICIAL LANGUAGE, SPOKEN LANGUAGE. The Romanian language - the only Romance language in Eastern Europe - is an "island" of Latinity in a mainly "Slavic sea" - including its dialects from the south of the Danube – Aromanian, Megleno-Romanian and Istro-Romanian. Multilingualism is defined narrowly as the alternative use of several languages; widely, it is use of several alternative language systems, regardless of their status: different languages, dialects of the same language or even varieties of the same idiom, being a natural consequence of linguistic contact. Multilingualism is an Europe value and a shared commitment, with particular importance for initial education, lifelong learning, employment, justice, freedom and security. Romanian language, with its four dialects - Daco-Romanian, Aromanian, Megleno- Romanian and Istro-Romanian – is the continuance of the Latin language spoken in the eastern parts of the former Roman Empire. Together with the Dalmatian language (now extinct) and central and southern Italian dialects, is part of the Apenino-Balkan group of Romance languages, different from theAlpine–Pyrenean group2. -

Language Contact in Pomerania: the Case of German, Polish, and Kashubian

P a g e | 1 Language Contact in Pomerania: The Case of German, Polish, and Kashubian Nick Znajkowski, New York University Purpose The effects of language contact and language shift are well documented. Lexical items and phonological features are very easily transferred from one language to another and once transferred, rather easily documented. Syntactic features can be less so in both respects, but shifts obviously do occur. The various qualities of these shifts, such as whether they are calques, extensions of a structure present in the modifying language, or the collapsing of some structure in favor the apparent simplicity found in analogous foreign structures, all are indicative of the intensity and the duration of the contact. Additionally, and perhaps this is the most interesting aspect of language shift, they show what is possible in the evolution of language over time, but also what individual speakers in a single generation are capable of concocting. This paper seeks to explore an extremely fascinating and long-standing language contact situation that persists to this day in Northern Poland—that of the Kashubian language with its dominating neighbors: Polish and German. The Kashubians are a Slavic minority group who have historically occupied the area in Northern Poland known today as Pomerania, bordering the Baltic Sea. Their language, Kashubian, is a member of the Slavic branch of Indo-European languages and further belongs to the Pomeranian branch of Lechitic languages, which includes Polish, Silesian, and the extinct Polabian and Slovincian. The situation to be found among the Kashubian people, a people at one point variably bi-, or as is sometimes the case among older folk, even trilingual in Kashubian, P a g e | 2 Polish, and German is a particularly exciting one because of the current vitality of the Kashubian minority culture. -

(Daco-Romanian and Aromanian) in Verbs of Latin Origin

CONJUGATION CHANGES IN THE EVOLUTION OF ROMANIAN (DACO-ROMANIAN AND AROMANIAN) IN VERBS OF LATIN ORIGIN AIDA TODI1, MANUELA NEVACI2 Abstract. Having as starting point for research on the change of conjugation of Latin to the Romance languages, the paper aims to present the situation of these changes in Romanian: Daco-Romanian (that of the old Romanian texts) and Aromanian dialect (which does not have a literary standard). Keywords: conjugation changes; Romance languages; Romanian language (Daco-Romanian and Aromanian). Conjugation changes are a characteristic feature of the Romance verb system. In some Romance languages (Spanish, Catalan, Portuguese, Sardinian) verbs going from one conjugation to another has caused the reduction of the four conjugations inherited from Latin to three inflection classes: in Spanish and Portuguese the 2nd conjugation extended (verbs with stressed theme vowel): véndere > Sp., Pg. vender; cúrere > Sp., Pg. correr; in Catalan 3rd conjugation verbs assimilated the 2nd conjugation ones, a phenomenon occurring in Sardinian as well: Catal. ventre, Srd. biere; Additionally, in Spanish and Portuguese the 4th conjugation also becomes strong, assimilating 3rd conjugation verbs: petĕre > Sp., Pg. petir, ungĕre> Sp., Pg. ungir, iungĕre> Sp., Pg. ungir (Lausberg 1988: 259). Lausberg includes Aromanian together with Spanish, Catalan and Sardinian, where the four conjugations were reduced to three, mentioning that 3rd conjugation verbs switched to the 2nd conjugation3. The process of switching from one conjugation to another is frequent from as early as vulgar Latin. Grammars experience changes such as: augĕre > augēre; ardĕre> ardēre; fervĕre > fervēre; mulgĕre> mulgēre; respondĕre> respondēre; sorbĕre> sorbēre; torquĕre > torquēre; tondĕre >tondēre (Densusianu 1961: 103, 1 “Ovidius” University, Constanţa, [email protected]. -

East European Languages

Latest Trends on Cultural Heritage and Tourism SEMANTIC CONCORDANCE IN THE SOUTH- EAST EUROPEAN LANGUAGES ANCUłA NEGREA, AGNES ERICH, ZLATE STEFANIA Faculty of Humanities Valahia University of Târgoviste Address: Street Lt. Stancu Ion, No. 35, Targoviste COUNTRY ROMANIA [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract: - The common terms of the southeast European languages that present semantic convergences [1], belong to a less explored domain, that of comparative linguistics. “The reason why the words have certain significations and not others is not found in the linguistic system or in the human biological or mental structures … it is the societies that, through their diverse history, determine the significations, and the semantics is found at the crossroads between the historical complexity of the reality it studies and the historical complexity of the culture reflecting on this reality… its object is the result and the condition of the historical character, thanks to the relations of mutual conditioning that relate the signification to the historic events of each human community.”[2] Key-Words: Balkan linguistics, terminology of the word “house”: Bg. kăšta, Srb., Cr. kuča, Maced. kuk’a, slov. koča < old sl. kotia meaning “what is hidden, what is sheltered”, Rom. casa < Lat. casa; Ngr. σπητη < Lat. hospitium; Alb. shtepi. 1 Introduction NeoGreek, and Albanese, present unanimous The “mentality” common to the Balkan world, concrdances for the terms having the meaning: having manifestations in the language, is the - “house”, “dwelling” and also historical product of the cohabitation in similar - ”room”, “place to live”, though these forms of civilization and culture. terms have different origins: Kristian SANDFELD, in his fundamental work - Bg. -

Christian Names for Catholic Boys and Girls

CHRISTIAN NAMES FOR CATHOLIC BOYS AND GIRLS CHRISTIAN NAMES FOR CATHOLIC BOYS AND GIRLS The moment has arrived to choose a Christian name for the baptism of a baby boys or girl. What should the child be called? Must he/she receive the name of a saint? According to the revised Catholic Church Canon Law, it is no longer mandatory that the child receive the name of a saint. The Canon Law states: "Parents, sponsors and parish priests are to take care that a name is not given which is foreign to Christian sentiment." [Canon # 855] In other words, the chosen name must appeal to the Christian community. While the names of Jesus and Judas are Biblical in nature, the choice of such names would result in controversy. To many, the Name Jesus is Sacred and the Most Holy of all names. Because Judas is the disciple who betrayed Jesus, many feel this would be a poor choice. Equally, names such as 'cadillac' or 'buick' are not suitable because they represent the individual person's personal interest in certain cars. The following is a short list of names that are suitable for boys and girls. Please keep in mind that this list is far from complete. NAMES FOR BOYS Aaron (Heb., the exalted one) Arthur (Celt., supreme ruler) Abel (Heb., breath) Athanasius (Gr., immortal) Abner (Heb., father of light) Aubrey (Fr., ruler) Abraham (Heb., father of a multitude) Augustine (Dim., of Augustus) Adalbert (Teut., nobly bright) Augustus (Lat., majestic) Adam (Heb., the one made; human Austin (Var., of Augustine) being; red earth) Adelbert (Var., of Adalbert) Baldwin (Teut., noble friend) Adrian (Lat., dark) Barnabas (Heb., son of consolation) Aidan (Celt., fire) Barnaby (Var., of Bernard) Alan (Celt., cheerful) Bartholomew (Heb., son of Tolmai) Alban (Lat., white) Basil (Gr., royal) Albert (Teut., illustrious) Becket (From St. -

Aleksey A. ROMANCHUK ROMANIAN a CINSTI in the LIGHT of SOME

2021, Volumul XXIX REVISTA DE ETNOLOGIE ȘI CULTUROLOGIE E-ISSN: 2537-6152 101 Aleksey A. ROMANCHUK ROMANIAN A CINSTI IN THE LIGHT OF SOME ROMANIAN-SLAVIC CONTACTS1 https://doi.org/10.52603/rec.2021.29.14 Rezumat определенное отражение следы обозначенного поздне- Cuvântul românesc a cinsti în lumina unor contacte праславянского диалекта (диалектов). В частности, к româno-slave таким следам, возможно, стоит отнести как украинские Pornind de la comparația dintre cuvântul ucrainean диалектные чандрий, шандрий, чендрий, так и диалект- частувати ‚a trata’ și românescul a cinsti‚ a trata (cu vin), ное (зафиксировано в украинском говоре с. Булэешть) / a bea vin, se consideră un grup de împrumuturi slave cu мон|золетеи/ ‘мусолить; впустую теребить’. /n/ epentetic în limba română, căreia îi aparține și a cin- Ключевые слова: славяне, румыны, лексические sti. Interpretând corpul de fapte disponibil, putem presu- заимствования, этническая история, украинские диа- pune că convergență semantică dintre cuvintele честь и лекты, Молдова, Буковина. угощение a apărut în perioada slavică timpurie. Cuvântul românesc a cinsti este un argument important pentru da- Summary tarea timpurie a apariției acestei convergențe semantice. Romanian a cinsti in the light of some Așadar, cuvântul ucrainean частувати, ca și cuvântul po- Romanian-Slavic contacts lonez częstowac, apar independent unul de celălalt, la fel A group of Slavic loanwords with epenthetic /n/ in the ca și de cuvântul românesc a cinsti. Cuvântul românesc a Romanian language, to which a cinsti belongs, is consid- cinsti, ca și, în general, grupul menționat de împrumuturi ered. Interpreting the existing set of facts, the author sup- slave cu /n/ epentetic în limba română, reprezintă un rezul- poses that the semantic convergence between the Slav- tat al contactelor timpurii ale limbii române cu un dialect ic честь ‘honour’ and угощение ‘treat’ appeared as far back (dialecte) slav vechi, pentru care era caracteristică tendința as the Late Slavic period. -

Arabic and Contact-Induced Change Christopher Lucas, Stefano Manfredi

Arabic and Contact-Induced Change Christopher Lucas, Stefano Manfredi To cite this version: Christopher Lucas, Stefano Manfredi. Arabic and Contact-Induced Change. 2020. halshs-03094950 HAL Id: halshs-03094950 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03094950 Submitted on 15 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Arabic and contact-induced change Edited by Christopher Lucas Stefano Manfredi language Contact and Multilingualism 1 science press Contact and Multilingualism Editors: Isabelle Léglise (CNRS SeDyL), Stefano Manfredi (CNRS SeDyL) In this series: 1. Lucas, Christopher & Stefano Manfredi (eds.). Arabic and contact-induced change. Arabic and contact-induced change Edited by Christopher Lucas Stefano Manfredi language science press Lucas, Christopher & Stefano Manfredi (eds.). 2020. Arabic and contact-induced change (Contact and Multilingualism 1). Berlin: Language Science Press. This title can be downloaded at: http://langsci-press.org/catalog/book/235 © 2020, the authors Published under the Creative Commons Attribution -

Esperanto, Civility, and the Politics of Fellowship: A

ESPERANTO, CIVILITY, AND THE POLITICS OF FELLOWSHIP: A COSMOPOLITAN MOVEMENT FROM THE EASTERN EUROPEAN PERIPHERY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Ana Velitchkova Omar Lizardo, Director Graduate Program in Peace Studies and Sociology Notre Dame, Indiana July 2014 © Copyright by ANA MILENOVA VELITCHKOVA 2014 All rights reserved ESPERANTO, CIVILITY, AND THE POLITICS OF FELLOWSHIP: A COSMOPOLITAN MOVEMENT FROM THE EASTERN EUROPEAN PERIPHERY Abstract by Ana Velitchkova This dissertation examines global, regional, state-, group-, and person-level processes involved in the growth of the movement formed around the constructed international language Esperanto. The Esperanto movement emerged in the global arena in the late nineteenth century as a response to inequalities in the nation-state field. In the course of several decades, the movement established a new global field based on the logic of equal communication through Esperanto and on the accumulation of cultural capital. While the field gained autonomy from the nation-state field, it has not been recognized as its equal. Persons endowed with cultural capital but lacking political and economic capital have been particularly drawn to Esperanto. Ironically, while attempting to overcome established unfair distinctions based on differential accumulation of political and economic capital, the Esperanto movement creates and maintains new distinctions and inequalities based on cultural capital accumulation. Ana Velitchkova At the regional level, the Esperanto movement became prominent in state- socialist Eastern Europe in the second half of the twentieth century. The movement found unexpected allies among independent states in the Eastern European periphery. -

The Balkan Vlachs/Aromanians Awakening, National Policies, Assimilation Miroslav Ruzica Preface the Collapse of Communism, and E

The Balkan Vlachs/Aromanians Awakening, National Policies, Assimilation Miroslav Ruzica Preface The collapse of communism, and especially the EU human rights and minority policy programs, have recently re-opened the ‘Vlach/Aromanian question’ in the Balkans. The EC’s Report on Aromanians (ADOC 7728) and its separate Recommendation 1333 have become the framework for the Vlachs/Aromanians throughout the region and in the diaspora to start creating programs and networks, and to advocate and shape their ethnic, cultural, and linguistic identity and rights.1 The Vlach/Aromanian revival has brought a lot of new and reopened some old controversies. A increasing number of their leaders in Serbia, Macedonia, Bulgaria and Albania advocate that the Vlachs/Aromanians are actually Romanians and that Romania is their mother country, Romanian language and orthography their standard. Such a claim has been officially supported by the Romanian establishment and scholars. The opposite claim comes from Greece and argues that Vlachs/Aromanians are Greek and of the Greek culture. Both countries have their interpretations of the Vlach origin and history and directly apply pressure to the Balkan Vlachs to accept these identities on offer, and also seek their support and political patronage. Only a minority of the Vlachs, both in the Balkans and especially in the diaspora, believes in their own identity or that their specific vernaculars should be standardized, and that their culture has its own specific elements in which even their religious practice is somehow distinct. The recent wars for Yugoslav succession have renewed some old disputes. Parts of Croatian historiography claim that the Serbs in Croatia (and Bosnia) are mainly of Vlach origin, i.e. -

The Moldavian and Romanian Dialectal Corpus

MOROCO: The Moldavian and Romanian Dialectal Corpus Andrei M. Butnaru and Radu Tudor Ionescu Department of Computer Science, University of Bucharest 14 Academiei, Bucharest, Romania [email protected] [email protected] Abstract In this work, we introduce the Moldavian and Romanian Dialectal Corpus (MOROCO), which is freely available for download at https://github.com/butnaruandrei/MOROCO. The corpus contains 33564 samples of text (with over 10 million tokens) collected from the news domain. The samples belong to one of the following six topics: culture, finance, politics, science, sports and tech. The data set is divided into 21719 samples for training, 5921 samples for validation and another 5924 Figure 1: Map of Romania and the Republic of samples for testing. For each sample, we Moldova. provide corresponding dialectal and category labels. This allows us to perform empirical studies on several classification tasks such as Romanian is part of the Balkan-Romance group (i) binary discrimination of Moldavian versus that evolved from several dialects of Vulgar Romanian text samples, (ii) intra-dialect Latin, which separated from the Western Ro- multi-class categorization by topic and (iii) mance branch of languages from the fifth cen- cross-dialect multi-class categorization by tury (Coteanu et al., 1969). In order to dis- topic. We perform experiments using a shallow approach based on string kernels, tinguish Romanian within the Balkan-Romance as well as a novel deep approach based on group in comparative linguistics, it is referred to character-level convolutional neural networks as Daco-Romanian. Along with Daco-Romanian, containing Squeeze-and-Excitation blocks. -

Hungarian Influence Upon Romanian People and Language from the Beginnings Until the Sixteenth Century

SECTION: HISTORY LDMD I HUNGARIAN INFLUENCE UPON ROMANIAN PEOPLE AND LANGUAGE FROM THE BEGINNINGS UNTIL THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY PÁL Enikő, Assistant Professor, PhD, „Sapientia” University of Târgu-Mureş Abstract: In case of linguistic contacts the meeting of different cultures and mentalities which are actualized within and through language are inevitable. There are some common features that characterize all kinds of language contacts, but in describing specific situations we will take into account different causes, geographical conditions and particular socio-historical settings. The present research focuses on the peculiarities of Romanian – Hungarian contacts from the beginnings until the sixteenth century insisting on the consequences of Hungarian influence upon Romanian people and language. Hungarians induced, directly or indirectly, many social and cultural transformations in the Romanian society and, as expected, linguistic elements (e.g. specific terminologies) were borrowed altogether with these. In addition, Hungarian language influence may be found on each level of Romanian language (phonetic, lexical etc.), its contribution consists of enriching the Romanian language system with new elements and also of triggering and accelerating some internal tendencies. In the same time, bilingualism has been a social reality for many communities, mainly in Transylvania, which contributed to various linguistic changes of Romanian language not only in this region, but in other Romanian linguistic areas as well. Hungarian elements once taken over by bilinguals were passed on to monolinguals, determining the development of Romanian language. Keywords: language contact, (Hungarian) language influence, linguistic change, bilingualism, borrowings Preliminary considerations Language contacts are part of everyday social life for millions of people all around the world (G. -

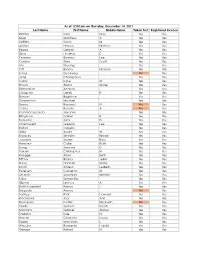

Last Name First Name Middle Name Taken Test Registered License

As of 12:00 am on Thursday, December 14, 2017 Last Name First Name Middle Name Taken Test Registered License Richter Sara May Yes Yes Silver Matthew A Yes Yes Griffiths Stacy M Yes Yes Archer Haylee Nichole Yes Yes Begay Delores A Yes Yes Gray Heather E Yes Yes Pearson Brianna Lee Yes Yes Conlon Tyler Scott Yes Yes Ma Shuang Yes Yes Ott Briana Nichole Yes Yes Liang Guopeng No Yes Jung Chang Gyo Yes Yes Carns Katie M Yes Yes Brooks Alana Marie Yes Yes Richardson Andrew Yes Yes Livingston Derek B Yes Yes Benson Brightstar Yes Yes Gowanlock Michael Yes Yes Denny Racheal N No Yes Crane Beverly A No Yes Paramo Saucedo Jovanny Yes Yes Bringham Darren R Yes Yes Torresdal Jack D Yes Yes Chenoweth Gregory Lee Yes Yes Bolton Isabella Yes Yes Miller Austin W Yes Yes Enriquez Jennifer Benise Yes Yes Jeplawy Joann Rose Yes Yes Harward Callie Ruth Yes Yes Saing Jasmine D Yes Yes Valasin Christopher N Yes Yes Roegge Alissa Beth Yes Yes Tiffany Briana Jekel Yes Yes Davis Hannah Marie Yes Yes Smith Amelia LesBeth Yes Yes Petersen Cameron M Yes Yes Chaplin Jeremiah Whittier Yes Yes Sabo Samantha Yes Yes Gipson Lindsey A Yes Yes Bath-Rosenfeld Robyn J Yes Yes Delgado Alonso No Yes Lackey Rick Howard Yes Yes Brockbank Taci Ann Yes Yes Thompson Kaitlyn Elizabeth No Yes Clarke Joshua Isaiah Yes Yes Montano Gabriel Alonzo Yes Yes England Kyle N Yes Yes Wiman Charlotte Louise Yes Yes Segay Marcinda L Yes Yes Wheeler Benjamin Harold Yes Yes George Robert N Yes Yes Wong Ann Jade Yes Yes Soder Adrienne B Yes Yes Bailey Lydia Noel Yes Yes Linner Tyler Dane Yes Yes