Recent Art from the Sigg and M+ Sigg Collections 19.02. – 19.06.2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Chen Qiulin), 25F a Cheng, 94F a Xian, 276 a Zhen, 142F Abso

Index Note: “f ” with a page number indicates a figure. Anti–Spiritual Pollution Campaign, 81, 101, 102, 132, 271 Apartment (gongyu), 270 “......” (Chen Qiulin), 25f Apartment art, 7–10, 18, 269–271, 284, 305, 358 ending of, 276, 308 A Cheng, 94f internationalization of, 308 A Xian, 276 legacy of the guannian artists in, 29 A Zhen, 142f named by Gao Minglu, 7, 269–270 Absolute Principle (Shu Qun), 171, 172f, 197 in 1980s, 4–5, 271, 273 Absolution Series (Lei Hong), 349f privacy and, 7, 276, 308 Abstract art (chouxiang yishu), 10, 20–21, 81, 271, 311 space of, 305 Abstract expressionism, 22 temporary nature of, 305 “Academic Exchange Exhibition for Nationwide Young women’s art and, 24 Artists,” 145, 146f Apolitical art, 10, 66, 79–81, 90 Academicism, 78–84, 122, 202. See also New academicism Appearance of Cross Series (Ding Yi), 317f Academic realism, 54, 66–67 Apple and thinker metaphor, 175–176, 178, 180–182 Academic socialist realism, 54, 55 April Fifth Tian’anmen Demonstration (Li Xiaobin), 76f Adagio in the Opening of Second Movement, Symphony No. 5 April Photo Society, 75–76 (Wang Qiang), 108f exhibition, 74f, 75 Adam and Eve (Meng Luding), 28 Architectural models, 20 Aestheticism, 2, 6, 10–11, 37, 42, 80, 122, 200 Architectural preservation, 21 opposition to, 202, 204 Architectural sites, ritualized space in, 11–12, 14 Aesthetic principles, Chinese, 311 Art and Language group, 199 Aesthetic theory, traditional, 201–202 Art education system, 78–79, 85, 102, 105, 380n24 After Calamity (Yang Yushu), 91f Art field (yishuchang), 125 Agree -

ASIAN Athletics 2 0 1 7 R a N K I N G S

ASIAN athletics 2 0 1 7 R a n k i n g s compiled by: Heinrich Hubbeling - ASIAN AA Statistician – C o n t e n t s Page 1 Table of Contents/Abbreviations for countries 2 - 3 Introduction/Details 4 - 9 Asian Continental Records 10 - 60 2017 Rankings – Men events 60 Name changes (to Women´s Rankings) 61 - 108 2017 Rankings – Women events 109 – 111 Asian athletes in 2017 World lists 112 Additions/Corrections to 2016 Rankings 113 - 114 Contacts for other publications etc. ============================================================== Abbreviations for countries (as used in this booklet) AFG - Afghanistan KGZ - Kyrghizstan PLE - Palestine BAN - Bangladesh KOR - Korea (South) PRK - D P R Korea BHU - Bhutan KSA - Saudi Arabia QAT - Qatar BRN - Bahrain KUW - Kuwait SGP - Singapore BRU - Brunei LAO - Laos SRI - Sri Lanka CAM - Cambodia LBN - Lebanon SYR - Syria CHN - China MAC - Macau THA - Thailand HKG - Hongkong MAS - Malaysia TJK - Tajikistan INA - Indonesia MDV - Maldives TKM - Turkmenistan IND - India MGL - Mongolia TLS - East Timor IRI - Iran MYA - Myanmar TPE - Chinese Taipei IRQ - Iraq NEP - Nepal UAE - United Arab E. JOR - Jordan OMA - Oman UZB - Uzbekistan JPN - Japan PAK - Pakistan VIE - Vietnam KAZ - Kazakhstan PHI - Philippines YEM - Yemen ============================================================== Cover Photo: MUTAZ ESSA BARSHIM -World Athlet of the Year 2017 -World Champion 2017 -World 2017 leader with 2.40 m (achieved twice) -undefeated during the 2017 season 1 I n t r o d u c t i o n With this booklet I present my 29th consecutive edition of Asian athletics statistics. As in the previous years I am very grateful to the ASIAN ATHLETICS ASSOCIATION and its secretary and treasurer, Mr Maurice Nicholas as well as to Mrs Regina Long; without their support I would not have been able to realise this project. -

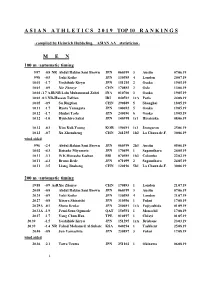

2019 TOP10-Rankings

A S I A N A T H L E T I C S 2 0 1 9 TOP 10 R A N K I N G S - compiled by Heinrich Hubbeling, ASIAN AA – statistician - M E N 100 m / automatic timing 9.97 +0.8 NR Abdul Hakim Sani Brown JPN 060399 3 Austin 07.06.19 9.98 +0.5 Yuki Koike JPN 130595 4 London 20.07.19 10.01 +1.7 Yoshihide Kiryu JPN 151295 2 Osaka 19.05.19 10.01 +0.9 Xie Zhenye CHN 170893 2 Oslo 13.06.19 10.03 +1.7 AJR/NR Lalu Muhammad Zohri INA 010700 3 Osaka 19.05.19 10.03 -0.3 NR=Hassan Taftian IRI 040593 1rA Paris 24.08.19 10.05 +0.9 Su Bingtian CHN 290889 5 Shanghai 18.05.19 10.11 +1.7 Ryota Yamagata JPN 100692 5 Osaka 19.05.19 10.12 +1.7 Shuhei Tada JPN 240696 6 Osaka 19.05.19 10.12 +1.0 Ryuichiro Sakai JPN 140398 1s1 Hiratsuka 08.06.19 10.12 -0.3 Kim Kuk-Young KOR 190491 1s1 Jeongseon 25.06.19 10.12 +0.7 Xu Zhouzheng CHN 261295 1h2 La Chaux-de-F. 30.06.19 wind-aided 9.96 +2.4 Abdul Hakim Sani Brown JPN 060399 2h3 Austin 05.06.19 10.02 +4.3 Daisuke Miyamoto JPN 170499 1 Sagamihara 24.05.19 10.11 +3.1 W.K.Himasha Eashan SRI 070595 1h3 Colombo 22.02.19 10.11 +4.3 Bruno Dede JPN 071099 2 Sagamihara 24.05.19 10.11 +3.5 Liang Jinsheng CHN 120196 5h1 La Chaux-de-F. -

P020200328433470342932.Pdf

In accordance with the relevant provisions of the CONTENTS Environment Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China, the Chongqing Ecology and Environment Statement 2018 Overview …………………………………………………………………………………………… 2 is hereby released. Water Environment ………………………………………………………………………………… 3 Atmospheric Environment ………………………………………………………………………… 5 Acoustic Environment ……………………………………………………………………………… 8 Solid and Hazardous Wastes ………………………………………………………………………… 9 Director General of Chongqing Ecology Radiation Environment …………………………………………………………………………… 11 and Environment Bureau Landscape Greening ………………………………………………………………………………… 12 May 28, 2019 Forests and Grasslands ……………………………………………………………………………… 12 Cultivated Land and Agricultural Ecology ………………………………………………………… 13 Nature Reserve and Biological Diversity …………………………………………………………… 15 Climate and Natural Disaster ……………………………………………………………………… 16 Eco-Priority & Green Development ………………………………………………………………… 18 Tough Fight for Pollution Prevention and Control ………………………………………………… 18 Ecological environmental protection supervision …………………………………………………… 19 Ecological Environmental Legal Construction ……………………………………………………… 20 Institutional Capacity Building of Ecological Environmental Protection …………………………… 20 Reform of Investment and Financing in Ecological Environmental Protection ……………………… 21 Ecological Environmental Protection Investment …………………………………………………… 21 Technology and Standards of Ecological Environmental Protection ………………………………… 22 Heavy Metal Pollution Control ……………………………………………………………………… 22 Environmental -

History Has Provided Ample Proof That the State Is the People, and the People Are the State

History has provided ample proof that the state is the people, and the people are the state. Winning or losing public support is vital to the Party's survival or extinction. With the people's trust and support, the Party can overcome all hardships and remain invincible. — Xi Jinping Contents Introduction… ………………………………………1 Chapter…One:…Why…Have…the…Chinese… People…Chosen…the…CPC?… ………………………4 1.1…History-based…Identification:… Standing…out…from…over…300…Political…Parties……… 5 1.2…Value-based…Identification:… Winning…Approval…through…Dedication… ………… 8 1.3…Performance-based…Identification:… Solid…Progress…in…People's…Well-being… ……………12 1.4…Culture-based…Identification:… Millennia-old…Faith…in…the…People… …………………16 Chapter…Two:…How…Does…the…CPC… Represent…the…People?… ……………………… 21 2.1…Clear…Commitment…to…Founding…Mission… ………22 2.2…Tried-and-true…Democratic…System… ………………28 2.3…Trusted…Party-People…Relationship… ………………34 2.4…Effective…Supervision…System… ………………………39 Chapter…Three:…What…Contributions…Does… the…CPC…Make…to…Human…Progress?… ……… 45 3.1…ABCDE:…The…Secret…to…the…CPC's…Success…from… a…Global…Perspective… ………………………………… 46 All…for…the…People… …………………………………… 46 Blueprint…Drawing… ………………………………… 47 Capacity…Building �������������� 48 Development…Shared… ……………………………… 50 Effective…Governance… ……………………………… 51 3.2…Community…with…a…Shared…Future…for…Humanity:… Path…toward…Well-being…for…All… …………………… 52 Peace…Built…by…All… …………………………………… 53 Development…Beneficial…to…All �������� 56 Mutual…Learning…among…Civilizations… ………… 59 Epilogue… ………………………………………… 62 Introduction Of the thousands of political parties in the world, just several dozen have a history of over 100 years, while only a select few have managed to stay in power for an extended period. -

LONDON SALES PREVIEW a Measured Market Outlook DESIGNS on LIFE Al and Kim Eiber at Home EYES on ASIA Shanghai and Regional M

TRIBAL ART IN SAN FRANCISCO MUMBAI SHUFFLE AT SOTHEBY’S NICOLA TYSON THE INTERNATIONAL MAGAZINE FOR ART COLLECTORS FEBRUARY 2016 LONDON SALES DESIGNS THE ART OF EYES ON PREVIEW ON LIFE ILLUSTRATION ASIA A Measured Al and Kim Eiber A Medium Shanghai and Market Outlook at Home on the Ascent Regional Markets MODERN & CONTEMPORARY ART Invitation to Consign TOM WESSELMANN (1931-2004) | Blonde Vivienne (Filled In), 1985/1995 | Alkyd oil on cut-out aluminum | 50 inches diameter Sold for: $317,000 October 28, 2015 Inquiries: 877-HERITAGE (437-4824) | Ext. 1444 | [email protected] DALLAS | NEW YORK | BEVERLY HILLS | SAN FRANCISCO | CHICAGO | PARIS | GENEVA | AMSTERDAM | HONG KONG Always Accepting Quality Consignments in 40 Categories 950,000+ Online Bidder-Members Paul R. Minshull #16591. BP 12-25%; see HA.com. 39536 Irving Penn . c I n , s n o t i Personal Work a c l i b u P t s a N é d n o C © 9 3 9 1 , k r o Y w e N 534 WEST 25TH ST NEW YORK ) , ( B o w JANUARY 29 – MARCH 5, 2016 d i n W p h o S ’ s n i a t i c p O , n n e P g i n v I r EX HI BI TI ON PAR IS: 10 - 11 FEBRU ARY LONDON: 2 2 - 2 3 FEB RUA RY COPENHAGEN: 25 - 29 FEBRUARY Hammershøi AUCTION COPENHAGEN: 1-10 MARCH 2016 ART, ANTIQUES AND DESIGN tel. +45 8818 1111 [email protected] bruun-rasmussen.com FEBRUARY 2016 FEATURES 56 IN THE STUDIO: NICOLA TYSON Known for her figurative practice in a range of media, the British-born artist prepares for a show of drawings at Petzel in New York. -

Staff and Students

KIB STAFF AND STUDENTS HAN Min CHEN Shao-Tian WANG Ying JI Yun-Heng Director: XUAN Yu CHEN Wen-Yun LI De-Zhu DUAN Jun-Hong GU Shuang-Hua The Herbarium Deputy Directors: PENG Hua (Curator) SUN Hang Sci. & Tech. Information Center LEI Li-Gong YANG Yong-Ping WANG Li-Song ZHOU Bing (Chief Executive) LIU Ji-Kai LI Xue-Dong LIU Ai-Qin GAN Fan-Yuan WANG Jing-Hua ZHOU Yi-Lan Director Emeritus: ZHANG Yan DU Ning WU Zheng-Yi WANG Ling HE Yan-Biao XIANG Jian-Ying HE Yun-Cheng General Administrative Offi ce LIU En-De YANG Qian GAN Fan-Yuan (Head, concurrent WU Xi-Lin post) ZHOU Hong-Xia QIAN Jie (Deputy Head) Biogeography and Ecology XIONG De-Hua Department Other Members ZHAO JI-Dong Head: ZHOU Zhe-Kun SHUI Yu-Min TIAN Zhi-Duan Deputy Head: PENG Hua YANG Shi-Xiong HUANG Lu-Lu HU Yun-Qian WU Yan CAS Key Laboratory of Biodiversity CHEN Wen-Hong CHEN Xing-Cai (Retired Apr. 2006) and Biogeography YANG Xue ZHANG Yi Director: SUN Hang (concurrent post) SU Yong-Ge (Retired Apr. 2006) Executive Director: ZHOU Zhe-Kun CAI Jie Division of Human Resources, Innovation Base Consultant: WU Master' s Students Zheng-Yi CPC & Education Affairs FANG Wei YANG Yun-Shan (secretary) WU Shu-Guang (Head) REN Zong-Xin LI Ying LI De-Zhu' s Group LIU Jie ZENG Yan-Mei LI De-Zhu ZHANG Yu-Xiao YIN Wen WANG Hong YU Wen-Bin LI Jiang-Wei YANG Jun-Bo AI Hong-Lian WU Shao-Bo XUE Chun-Ying ZHANG Shu PU Ying-Dong GAO Lian-Ming ZHOU Wei HE Hai-Yan LU Jin-Mei DENG Xiao-Juan HUA Hong-Ying TIAN Xiao-Fei LIU Pei-Gui' s Group LIANG Wen-Xing XIAO Yue-Qin LIU Pei-Gui QIAO Qin ZHANG Chang-Qin Division of Science and TIAN Wei WANG Xiang-Hua Development MA Yong-Peng YU Fu-Qiang WANG Yu-Hua (Head) SHEN Min WANG Yun LI Zhi-Jian ZHU Wei-Dong MA Xiao-Qing SUN Hang' s Group NIU Yang YUE Yuan-Zheng SUN Hang YUE Liang-Liang LI Xiao-Xian NIE Ze-Long LI Yan-Chun TIAN Ning YUE Ji-Pei FENG Bang NI Jing-Yun ZHA Hong-Guang XIA Ke HU Guo-Wen (Retired Jun. -

China COI Compilation-March 2014

China COI Compilation March 2014 ACCORD is co-funded by the European Refugee Fund, UNHCR and the Ministry of the Interior, Austria. Commissioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Division of International Protection. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it endorse, its content. Any views expressed are solely those of the author. ACCORD - Austrian Centre for Country of Origin & Asylum Research and Documentation China COI Compilation March 2014 This COI compilation does not cover the Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macau, nor does it cover Taiwan. The decision to exclude Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan was made on the basis of practical considerations; no inferences should be drawn from this decision regarding the status of Hong Kong, Macau or Taiwan. This report serves the specific purpose of collating legally relevant information on conditions in countries of origin pertinent to the assessment of claims for asylum. It is not intended to be a general report on human rights conditions. The report is prepared on the basis of publicly available information, studies and commentaries within a specified time frame. All sources are cited and fully referenced. This report is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, or conclusive as to the merits of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Every effort has been made to compile information from reliable sources; users should refer to the full text of documents cited and assess the credibility, relevance and timeliness of source material with reference to the specific research concerns arising from individual applications. -

2004 V03 03 Wu H P005.Pdf

: Figure 1. Marc Riboud, A Student in the Central Academy of Fine Arts Making an Image of Mao Zedong, 1957, black-and-white photography. Courtesy of Chambers Fine Art The exhibition Intersection,presented at Chambers Fine Art in New York City in June 2004, deals with a fundamental issue in contemporary Chinese art: the interrelationship between photography and painting. It is fundamental because few oil painters and photographers in post-Cultural Revolution China can escape this interrelationship which has influenced and even controlled their art in different ways and on multiple levels. From the 1960s through the 1980s, photography provided painting with a state sanctioned reality to depict (although the content of this reality changed greatly over time), while most “experimental photographers” (shiyan sheyingjia) that emerged in the 1990s and early 2000s were first trained as painters or graphic artists. How do painting and photography interact with each other in today’s Chinese art? To Chen Danqing, one of the six artists featured in this exhibition, “copying [photographs in oil] is not to imitate other people’s language. Like playing musical compositions, copying is itself a language.”The other five artists each answer the question differently; but all have problematized the painting/photography relationship in their works. By doing so, these artists—three photographers and three oil painters—demonstrate how this relationship has become a shared focus of their artistic experi- mentation. To understand the experimental nature of their works, however, we need to briefly reflect upon the connections between painting and photography in Chinese art since the 1960s. *** “Painting from photographs” became a legitimate artistic practice during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), when numerous paintings—portraits of Mao Zedong and his wife Jiang Qing, heroic images of the revolutionary masses, and narrative pictures of the Party’s glorious history—were Figure 2. -

Factory Name

Factory Name Factory Address BANGLADESH Company Name Address AKH ECO APPARELS LTD 495, BALITHA, SHAH BELISHWER, DHAMRAI, DHAKA-1800 AMAN GRAPHICS & DESIGNS LTD NAZIMNAGAR HEMAYETPUR,SAVAR,DHAKA,1340 AMAN KNITTINGS LTD KULASHUR, HEMAYETPUR,SAVAR,DHAKA,BANGLADESH ARRIVAL FASHION LTD BUILDING 1, KOLOMESSOR, BOARD BAZAR,GAZIPUR,DHAKA,1704 BHIS APPARELS LTD 671, DATTA PARA, HOSSAIN MARKET,TONGI,GAZIPUR,1712 BONIAN KNIT FASHION LTD LATIFPUR, SHREEPUR, SARDAGONI,KASHIMPUR,GAZIPUR,1346 BOVS APPARELS LTD BORKAN,1, JAMUR MONIPURMUCHIPARA,DHAKA,1340 HOTAPARA, MIRZAPUR UNION, PS : CASSIOPEA FASHION LTD JOYDEVPUR,MIRZAPUR,GAZIPUR,BANGLADESH CHITTAGONG FASHION SPECIALISED TEXTILES LTD NO 26, ROAD # 04, CHITTAGONG EXPORT PROCESSING ZONE,CHITTAGONG,4223 CORTZ APPARELS LTD (1) - NAWJOR NAWJOR, KADDA BAZAR,GAZIPUR,BANGLADESH ETTADE JEANS LTD A-127-131,135-138,142-145,B-501-503,1670/2091, BUILDING NUMBER 3, WEST BSCIC SHOLASHAHAR, HOSIERY IND. ATURAR ESTATE, DEPOT,CHITTAGONG,4211 SHASAN,FATULLAH, FAKIR APPARELS LTD NARAYANGANJ,DHAKA,1400 HAESONG CORPORATION LTD. UNIT-2 NO, NO HIZAL HATI, BAROI PARA, KALIAKOIR,GAZIPUR,1705 HELA CLOTHING BANGLADESH SECTOR:1, PLOT: 53,54,66,67,CHITTAGONG,BANGLADESH KDS FASHION LTD 253 / 254, NASIRABAD I/A, AMIN JUTE MILLS, BAYEZID, CHITTAGONG,4211 MAJUMDER GARMENTS LTD. 113/1, MUDAFA PASCHIM PARA,TONGI,GAZIPUR,1711 MILLENNIUM TEXTILES (SOUTHERN) LTD PLOTBARA #RANGAMATIA, 29-32, SECTOR ZIRABO, # 3, EXPORT ASHULIA,SAVAR,DHAKA,1341 PROCESSING ZONE, CHITTAGONG- MULTI SHAF LIMITED 4223,CHITTAGONG,BANGLADESH NAFA APPARELS LTD HIJOLHATI, -

Shi Jinsong Born 1969 in Hubei, China

Shi Jinsong Born 1969 in Hubei, China. Lives and works in Wuhan and Beijing. EDUCATION 1994 B.F.A., Sculpture Department, Hubei Institute of Fine Arts, Hubei, China SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2021 Shi Jinsong: Sky, How Art Museum, Shanghai 2019 Grand Canal, Times Art Museum, Beijing Shades of Gray 2012-2019, Art Museum of Hubei Provincial Academy of Fine Arts, Wuhan, China 2018 Shi Jinsong Solo Exhibition, Fine Arts Literature Art Center, Wuhan, China All That is Solid Melts into Air: A Solo Exhibition by Shi Jinsong in Taipei, Mind Set Art Center, Taipei Shi Jinsong: Speak Up, Gray, X Gallery, Beijing Shi Jinsong: Third Reproduction, Whitebox Art Center, Beijing 2016 Shi Jin-song: A Personal Design Show, Museum of Contemporary Art Taipei, Taipei; Space Station, Beijing 2015 Shi Jinsong's Art Fair: Free Download, Klein Sun Gallery, New York 2014 Shi Jinsong: Art Materials Company Owner's Garden, Phoenix Art Palace Center, Shanghai 2013 Shi Jinsong: Scenes from an Unpredictable Theatre - Not the Ending, Chung Shan Creative Hub, Taipei Shi Jinsong: Ite, Missa est, FEIZI Gallery, Brussels, Belgium 2012 Shi Jinsong: Scenes from an Unpredictable Theatre - Zero Insurrection, Chung Shan Creative Hub, Taipei Shi Jinsong: Pavilion Garden, Mind Set Art Center, Taipei 2011 Penetrate - New Works of Shi Jinsong, Today Art Museum, Beijing 2010 Shi Jinsong: Jamsil, SOMA Museum of Art, Seoul 398 West Street, New York, NY 10014 | T: +1.212.255.4388 | [email protected] | www.galleryek.com 2009 Shi Jinsong: Take off the Armor's Mountain, Space Station, Beijing Shi -

Long Marchers on the Road: Biographies Thinkers & Artists

Long Marchers on the Road: Biographies Thinkers & Artists Johnson Chang Tsong-zung is a curator, guest professor at the China Art Academy, art director of Hanart TZ Gallery, co-founder of the Asia Art Archive in Hong Kong, and co-founder of the Hong Kong chapter of International Association of Art Critics (AICA). He has curated Chinese exhibitions since the 1980s, pioneered the participation of Chinese artists in international exhibitions, and was instrumental in establishing the international image of Chinese contemporary art of the 1990s. Margaret Chen studied Journalism (B.A.) at Fudan University, Shanghai, and Communications (M.Phil.) at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. After working at Shanghai Zendai Museum of Modern Art in 2007, she joined Ullens Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing and worked in the Education & Public Programs and Exhibitions Departments. In March 2010, she moved back to Shanghai to participate in the West Heavens Project. Chen Chieh-jen is a renowned Taiwanese artist based in Taipei. In the 1980s, he emerged as a prominent figure of the Taiwanese art scene with his guerrilla-style performances and underground exhibitions. Since 1996, he has been working primarily in film and photography, seeking to re-examine forgotten historical memories of Taiwan hidden under the dominance of neoliberal rhetoric in Taiwanese society today. Brian Doan is an artist and photographer based in Los Angeles. He received his M.F.A. from Massachusetts College of Art, Boston and currently teaches photography at the Long Beach City College, Los Angeles. Brian was born in Vietnam and immigrated with his family to the U.S.A.