Micronesian Educator, Volume 25, 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visual/Media Arts

A R T I S T D I R E C T O R Y ARTIST DIRECTORY (Updated as of August 2021) md The Guam Council on the Arts and Humanities Agency (GCAHA) has produced this Artist Directory as a resource for students, the community, and our constituents. This Directory contains names, contact numbers, email addresses, and mailing or home address of Artists on island and the various disciplines they represent. If you are interested in being included in the directory, please call our office at 300-1204~8/ 7583/ 7584, or visit our website (www.guamcaha.org) to download the Artist Directory Registration Form. TABLE OF CONTENTS DISCIPLINE PAGE NUMBER FOLK/ TRADITIONAL ARTS 03 - 17 VISUAL/ MEDIA ARTS 18 - 78 PERFORMING ARTS 79 - 89 LITERATURE/ HUMANITIES 90 - 96 ART RELATED ORGANIZATIONS 97 – 100 MASTER’S 101 - 103 2 FOLK/ TRADITIONAL ARTS Folk Arts enriches the lives of the Guam community, gives recognition to the indigenous and ethnic artists and their art forms and to promote a greater understanding of Guam’s native and multi-ethnic community. Ronald Acfalle “ Halu’u” P.O. BOX 9771 Tamuning, Guam 96931 [email protected] 671-689-8277 Builder and apprentice of ancient Chamorro (seafaring) sailing canoes, traditional homes and chanter. James Bamba P.O. BOX 26039 Barrigada, Guam 96921 [email protected] 671-488-5618 Traditional/ Contemporary CHamoru weaver specializing in akgak (pandanus) and laagan niyok (coconut) weaving. I can weave guagua’ che’op, ala, lottot, guaha, tuhong, guafak, higai, kostat tengguang, kustat mama’on, etc. Arisa Terlaje Barcinas P.O.BOX 864 Hagatna, Guam 96932 671-488-2782, 671-472-8896 [email protected] Coconut frond weaving in traditional and contemporary styles. -

Bus Schedule Carmel Catholic School Agat and Santa Rita Area to Mount Bus No.: B-39 Driver: Salas, Vincent R

BUS SchoolSCHEDULE Year 2020 - 2021 Dispatcher Bus Operations - 646-3122 | Superintendent Franklin F. Tait ano - 646-3208 | Assistant Superintendent Daniel B. Quintanilla - 647-5025 THE DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS, BUS OPERATIONS REQUIRES ALL STUDENTS TO WEAR A MASK PRIOR TO BOARDING THE BUS. THERE WILL BE ONE CHILD PER SEAT FOR SOCIAL DISTANCING. PLEASE ANTICIPATE DELAYS IN PICK UP AND DROP OFF AT DESIGNATED BUS SHELTERS. THANK YOU. TENJO VISTA AND SANTA RITA AREAS TO O/C-30 Hanks 5:46 2:29 OCEANVIEW MIDDLE SCHOOL O/C-29 Oceanview Drive 5:44 2:30 A-2 Tenjo Vista Entrance 7:30 4:01 O/C-28 Nimitz Hill Annex 5:40 2:33 A-3 Tenjo Vista Lower 7:31 4:00 SOUTHERN HIGH SCHOOL 6:15 1:50 AGAT A-5 Perez #1 7:35 3:56 PAGACHAO AREA TO MARCIAL SABLAN DRIVER: AGUON, DAVID F. A-14 Lizama Station 7:37 3:54 ELEMENTARY SCHOOL (A.M. ONLY) BUS NO.: B-123 A-15 Borja Station 7:38 3:53 SANTA ANA AREAS TO SOUTHERN HIGH SCHOOL A-38 Pagachao Upper 7:00 A-16 Naval Magazine 7:39 3:52 MARCIAL SABLAN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 7:10 STATION LOCATION NAME PICK UP DROP OFF A-17 Sgt. Cruz 7:40 3:51 A-44 Tracking Station Entrance 5:50 2:19 A-18 M & R Store 7:41 3:50 PAGACHAO AREA TO OCEANVIEW MIDDLE A-43 Cruz #2 5:52 2:17 SCHOOL A-42 San Nicolas 5:54 2:15 A-19 Annex 7:42 3:49 A-41 Quidachay 5:56 2:12 A-20 Rapolla Station 7:43 3:48 A-46 Round Table 7:15 3:45 A-40 Santa Ana 5:57 2:11 OCEANVIEW MIDDLE SCHOOL 7:50 3:30 A-38 Pagachao Upper 7:22 3:53 A-39 Last Stop 5:59 2:10 A-37 Pagachao Lower 7:25 3:50 SOUTHERN HIGH SCHOOL 6:11 1:50 HARRY S. -

Download This Volume

Photograph by Carim Yanoria Nåna by Kisha Borja-Quichocho Like the tåsa and haligi of the ancient Chamoru latte stone so, too, does your body maintain the shape of the healthy Chamoru woman. With those full-figured hips features delivered through natural birth for generations and with those powerful arms reaching for the past calling on our mañaina you have remained strong throughout the years continuously inspire me to live my culture allow me to grow into a young Chamoru woman myself. Through you I have witnessed the persistence and endurance of my ancestors who never failed in constructing a latte. I gima` taotao mo`na the house of the ancient people. Hågu i acho` latte-ku. You are my latte stone. The latte stone (acho` latte) was once the foundation of Chamoru homes in the Mariana Islands. It was carved out of limestone or basalt and varied in size, measuring between three and sixteen feet in height. It contained two parts, the tasa (a cup-like shape, the top portion of the latte) and the haligi (the bottom pillar) and were organized into two rows, with three to seven latte stones per row. Today, several latte stones still stand, and there are also many remnants of them throughout the Marianas. Though Chamorus no longer use latte stones as the foundations of their homes, the latte symbolize the strength of the Chamorus and their culture as well as their resiliency in times of change. Micronesian Educator Editor: Unaisi Nabobo-Baba Special Edition Guest Editors: Michael Lujan Bevacqua Victoria Lola Leon Guerrero Editorial Board: Donald Rubinstein Christopher Schreiner Editorial Assistants: Matthew Raymundo Carim Yanoria Design and Layout: Pascual Olivares ISSN 1061-088x Published by: The School of Education, University of Guam UOG Station, Mangilao, Guam 96923 Contents Guest Editor’s Introduction ............................................................................................................... -

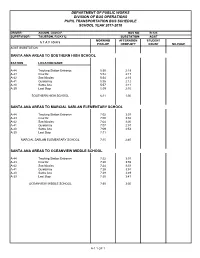

Department of Public Works Division of Bus Operations Pupil Transportation Bus Schedule School Year 2017-2018

DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS DIVISION OF BUS OPERATIONS PUPIL TRANSPORTATION BUS SCHEDULE SCHOOL YEAR 2017-2018 DRIVER: AGUON, DAVID F. BUS NO. B-123 SUPERVISOR: TAIJERON, RICKY U. SUBSTATION: AGAT MORNING AFTERNOON STUDENT S T A T I O N S PICK-UP DROP-OFF COUNT MILEAGE AGAT SUBSTATION SANTA ANA AREAS TO SOUTHERN HIGH SCHOOL STATION LOCATION NAME A-44 Tracking Station Entrance 5:50 2:19 A-43 Cruz #2 5:52 2:17 A-42 San Nicolas 5:54 2:15 A-41 Quidachay 5:56 2:12 A-40 Santa Ana 5:57 2:11 A-39 Last Stop 5:59 2:10 SOUTHERN HIGH SCHOOL 6:11 1:50 SANTA ANA AREAS TO MARCIAL SABLAN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL A-44 Tracking Station Entrance 7:02 3:03 A-43 Cruz #2 7:00 3:02 A-42 San Nicolas 7:04 3:00 A-41 Quidachay 7:07 2:57 A-40 Santa Ana 7:09 2:53 A-39 Last Stop 7:11 MARCIAL SABLAN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 7:15 2:40 SANTA ANA AREAS TO OCEANVIEW MIDDLE SCHOOL A-44 Tracking Station Entrance 7:22 3:57 A-43 Cruz #2 7:20 3:55 A-42 San Nicolas 7:24 3:53 A-41 Quidachay 7:26 3:51 A-40 Santa Ana 7:28 3:49 A-39 Last Stop 7:30 3:47 OCEANVIEW MIDDLE SCHOOL 7:35 3:30 A-1 1 OF 1 DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS DIVISION OF BUS OPERATIONS PUPIL TRANSPORTATION BUS SCHEDULE SCHOOL YEAR 2017-2018 DRIVER: BORJA, GARY P. -

Teachers Guide.Pages

I HINANAO-TA NU I MANAOTAO TÅNO’-I CHAMORU SIHA The Journey of the CHamoru People The Guam Museum’s Permanent Exhibition Teacher’s Guide Produced by Guampedia I HINANAO-TA NU I MANAOTAO TÅNO’-I CHAMORU SIHA The Journey of the CHamoru People The Guam Museum’s Permanent Exhibition Teacher’s Guide Note to readers: Underlined words in this document are links to entries in guampedia.com and other online resources. Guam Museum Permanent Exhibition Overview History of the Guam Museum The Guam Museum, officially called the Senator Antonio M. Palomo Guam and CHamoru Educational Facility, is the first structure built for the sole purpose of housing and displaying Guam’s precious historic treasures. The Guam Museum reflects the diversity, creativity, and resilience of the people of Guam and the Mariana Islands. The permanent exhibition is the story of the CHamoru people, told from a CHamoru perspective. It is hoped to encourage people to engage in dialogue, to share perspectives and experiences and debate issues that concern us all today. I Hale’ta: Mona yan Tatte: 90 Years in the Making The earliest printed record of people making plans for a new museum dates back to 1926. The Guam Teachers Association, led by Ramon M. Sablan, a teacher best known as the author of the “Guam Hymn,” asked residents and friends of Guam to start collecting their antiques and other artifacts for a museum that would protect their history and CHamoru culture. The editor of the Guam Recorder, one of the earliest publications printed and circulated on Guam, also called for the opening of a museum. -

AAPI National Historic Landmarks Theme Study Essay 12

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior A National Historic Landmarks Theme Study ASIAN AMERICAN PACIFIC ISLANDER ISLANDER AMERICAN PACIFIC ASIAN Finding a Path Forward ASIAN AMERICAN PACIFIC ISLANDER NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS THEME STUDY LANDMARKS HISTORIC NATIONAL NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS THEME STUDY Edited by Franklin Odo Use of ISBN This is the official U.S. Government edition of this publication and is herein identified to certify its authenticity. Use of 978-0-692-92584-3 is for the U.S. Government Publishing Office editions only. The Superintendent of Documents of the U.S. Government Publishing Office requests that any reprinted edition clearly be labeled a copy of the authentic work with a new ISBN. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Odo, Franklin, editor. | National Historic Landmarks Program (U.S.), issuing body. | United States. National Park Service. Title: Finding a Path Forward, Asian American and Pacific Islander National Historic Landmarks theme study / edited by Franklin Odo. Other titles: Asian American and Pacific Islander National Historic Landmarks theme study | National historic landmark theme study. Description: Washington, D.C. : National Historic Landmarks Program, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 2017. | Series: A National Historic Landmarks theme study | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2017045212| ISBN 9780692925843 | ISBN 0692925848 Subjects: LCSH: National Historic Landmarks Program (U.S.) | Asian Americans--History. | Pacific Islander Americans--History. | United States--History. Classification: LCC E184.A75 F46 2017 | DDC 973/.0495--dc23 | SUDOC I 29.117:AS 4 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017045212 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. -

HR 4686 EH 3 1 Prehistoric Site That Is Surrounded by Tall-Canopy 2 Limestone Forest

111TH CONGRESS 2D SESSION H. R. 4686 AN ACT To authorize the Secretary of the Interior to study the suit- ability and feasibility of designating prehistoric, historic, and limestone forest sites on Rota, Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, as a unit of the National Park System. 1 Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representa- 2 tives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, 2 1 SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE; FINDINGS. 2 (a) SHORT TITLE.—This Act may be cited as the 3 ‘‘Rota Cultural and Natural Resources Study Act’’. 4 (b) FINDINGS.—Congress finds as follows: 5 (1) The island of Rota was the only major is- 6 land in the Mariana Islands to be spared the de- 7 struction and large scale land use changes brought 8 about by World War II. 9 (2) The island of Rota has been described by 10 professional archeologists as having the most numer- 11 ous, most intact, and generally the most unique pre- 12 historic sites of any of the islands of the Mariana 13 Archipelago. 14 (3) The island of Rota contains remaining ex- 15 amples of what is known as the Latte Phase of the 16 cultural tradition of the indigenous Chamorro people 17 of the Mariana Islands. Latte stone houses are rem- 18 nants of the ancient Chamorro culture. 19 (4) Four prehistoric sites are listed on the Na- 20 tional Register of Historic Places: Monchon Archeo- 21 logical District (also known locally as Monchon 22 Latte Stone Village), Taga Latte Stone Quarry, the 23 Dugi Archeological Site that contains, latte stone 24 structures, and the Chugai Pictograph Cave that 25 contains examples of ancient Chamorro rock art. -

March 2017 | Volume 6, Issue No

March 2017 | Volume 6, Issue No. 1 Håfa Adai Everyday Håfa Adai Pledge Program Reaches Milestone Åmot Farm Inc. became the 700th member of the Håfa Adai Pledge program on Thursday, March 9 in Dededo. It marked a milestone for the Guam Visitors Bureau’s local community branding campaign. From left: Miranda Muñoz, GVB administrative assistant; Dee Hernandez, GVB cultural heritage ocer; Clare Calvo, Åmot Farm Inc. board member; Jon Nathan Denight, GVB president and CEO; Rose Cunlie, GVB director of finance and administration; Senator Tina Muña Barnes, 33rd Guam Legislature; Bernice T. Nelson, Åmot Farm Inc. suruhana and farm manager; Frank Rabon, Åmot Farm Inc. board chairman; Bill McDonald, Åmot Farm Inc. board member; Liz Stinson, board member; Mayor Melissa B. Savares, village of Dededo, mayor; Gwendolyn Tudela Aguon, Åmot Farm Inc. consultant; Senator Joe S. San Agustin, 34th Guam Legislature; Seb Pehlivanian, DPHSS NCD community gardens member; Zina Ruiz, Åmot Farm Inc. secretary; Ronald T. Laguana, Åmot Farm Inc., board member; and Retta Sue Hamilton, Åmot Farm Inc. executive director. 34th Guam Legislature Takes Håfa Adai Pledge: The Guam Visitors Bureau welcomed the 34th Guam Legislature to the Håfa Adai Pledge program. Senators took the pledge at a special ceremony on Friday, March 10 in the Guam Legislature building in Hagåtña. From left: Sen. Louise B. Muna; Sen. Mary C. Torres; Sen. Frank B. Aguon Jr.; Vice Speaker Therese M. Terlaje; Bart Jackson, GVB board member; Speaker Benjamin J.F. Cruz; Sen. Dennis G. Rodriguez Jr., chairman of tourism committee; Pilar Laguana, GVB director of global marketing; Young Sook Hong, GVB board member; Sen. -

An Overview of Latte Period Archaeology

Micronesica 42(1/2): 1–79, 2012 An overview of latte period archaeology MIKE T. CARSON Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, Mangilao, GU 96923 USA Abstract—Studies of megalithic ruins called latte and other related material traces potentially offer insights into an associated latte period, approximately A.D. 900 through 1700, quite distinctive from preceding cultural periods that began as early at 1500 B.C. in the Mariana Islands. Vastly more is known of this latte period than any other in Marianas regional archaeology, yet numerous basic questions continue to be considered and debated. The present work aims to summarize current data and thinking about latte research. Introduction The theme “archaeological studies of the latte period” was chosen for this volume of Micronesica to embrace the plentiful ways archaeologists and others conceptualize these megalithic ruins and their significance toward indigenous cultural history and heritage in the Mariana Islands (Figure 1). Today, latte stones vibrantly symbolize native Chamorro cultural identity (Figure 2), and they embody a material link to an ancestral society prior to the last few centuries of foreign colonial rule and evolving globalized context of the Chamorro people. During the last several decades of archaeological study, latte sites and their multiple associations have proven to be quite complex, deserving equally complex modes of study. Interpretive models are even more complicated in attempts to comprehend or explain the functions of latte stones and the evolution of native Chamorro society associated with these ancient sites. In common usage, the word latte refers to sets of megalithic pillars (haligi) and “caps” or capitals (tasa) that at one time presumably supported wooden superstructures (Figure 3). -

Guam Guide Book

Hafa Adai, Each section of the Guam Guide, detailed in the Table of and Contents, is separated using welcome to Guam! different colored latte stones on the margin of each page. This will help you to explore his Guam Guide includes the book and our island easily. Teverything you need to know about our island in one One important thing to keep easy-to-read format. From our in mind as you make your way rich Chamorro culture to our through the Guam Guide is heritage, food, and even that you can find a listing of all historical landmarks that make hotels, restaurants, scenic our island unique, you will find spots, shopping and everything you need to transportation options – along explore our tropical paradise with other members of the in these pages. Guam Visitors Bureau – in the back pocket. Maps can be found throughout the book, particularly in the Please use this listing to help Sightseeing & Landmarks plan your stay on our beautiful section, which offers a island or visit the GVB website detailed listing of WWII sites, at www.visitguam.com. favorite beaches, and other We hope you enjoy your stay Guam hotspots that may be of on Guam, “Where America’s interest to you. day begins.” 1 USING THIS GUIDE CONTENTS Using this Guide. 2 Guam’s Unique Culture and Proud Heritage . 4 Fruits & Flowers of Guam . 6 Village Murals . 7 Your Guam Experience . 8 History of Guam. 10 Planning Your Visit . 16 Getting Around . 19 Family Fun in the Sun . 20 · Beaches . 20 · Outdoor Activities. 24 · Snorkeling . -

Latte Villages in Guam and the Marianas: Monumentality Or Monumenterity?

Micronesica 42(1/2): 183–208, 2012 Latte villages in Guam and the Marianas: Monumentality or monumenterity? JOHN A. PETERSON Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, Mangilao, GU 96923 USA Abstract—The functions of latte structures in Guam and the Marianas have been treated in two significant perspectives that deserve examination relative to their monumental character. The classic ethnographic and ethnohistoric perspective interpreted latte structures as part of village complexes with both residential and communal functions. Materialistic interpretations have characterized latte structures as chiefly houses with size possibly denoting relative power or rank among villagers and villages in the Marianas. However, examination of paleoenvironmental data, recent migration models depicting dispersal of matrilineal clans from the eastern Caroline Islands westward throughout what is now Micronesia, along with data from site surveys, excavations, and linguistic and ethnographic sources demonstrate that latte period settlement and architecture of the second millennium A.D. shares architectural styles, material culture, and lifeways with Micronesian islands to the east in what may have been a second and diffuse migrational movement through the region. In this model latte architecture expresses shared inter-village identities and mechanisms for conflict resolution rather than competition, warfare, and socio-economic ranking. Introduction “Classified according to length of ground-plan, there are three types of latte, namely, small, medium, and large…furthermore, increase in size is achieved in length and height only, while the width is constant, a characteristic of Oceanian house types in which the width of the building is limited by the length of the wooden cross- beams”(Thompson 1940: 448,458). -

Review of Archaeological and Historical Data Concerning Reef Fishing in the U.S. Flag Islands of Micronesia: Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands

Final Report August 2003 REVIEW OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL DATA CONCERNING REEF FISHING IN THE U.S. FLAG ISLANDS OF MICRONESIA: GUAM AND THE NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS By Judith R. Amesbury and Rosalind L. Hunter-Anderson Micronesian Archaeological Research Services A Guam Non-Profit Corporation PO Box 22303; GMF, Guam 96921 A Council Authorized by the Magnuson Fishery Conservation and Management Act of 1976 1164 BISHOP STREET A SUITE 1400 A HONOLULU A HAWAII 96813 USA A TELEPHONE (808) 522-8220 A FAX (808) 522-8226 www.wpcouncil.org Cover Photograph: Chamorro women net fishing. Source: Unpublished Sketch from the Freycinet Expedition. Courtesy of the Commonwealth Museum of History and Culture A publication of the Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council pursuant to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Award No.NA97FCOI90 The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author and does not necessarily reflect the views of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration or the Department of Commerce Final Report REVIEW OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL DATA CONCERNING REEF FISHING IN THE U.S. FLAG ISLANDS OF MICRONESIA: GUAM AND THE NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS By Judith R. Amesbury and Rosalind L. Hunter-Anderson Prepared for Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council 1164 Bishop Street, Suite 1400 Honolulu, Hawai’i 96813 Micronesian Archaeological Research Services A Guam Non-Profit Corporation P.O. Box 22303; GMF, Guam 96921 August 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES