Download This Volume

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political Status and External Affairs Subcommittee Transition Report

Political Status and External Affairs Subcommittee Transition Report The report for the Political Status and External Affairs Subcommittee for the incoming Calvo- Tenorio Administration has been divided into two sections. The first section addresses the Commission on Decolonization and the Political Status issue for Guam, and the second section addresses the issues related to External Affairs. I. Political Status Overall Description or Mission of Department/Agency The Commission on Decolonization created by Public Law 23-147 has been inactive for a number of years. The legislation creating the Commission was enacted by I Mina’ Benti Tres na Liheslaturan Guåhan, notwithstanding the objections of the Governor, mandated the creation of a Commission on Decolonization. (PL 23-147 was overridden with sixteen (16) affirmative votes (including those of current Speaker Judi Won Pat, Senators Tom C. Ada and Vicente C. Pangelinan – incumbent Senators who have successfully retained their seats for I Mina’ Trentai Uno na Liheslaturan Guåhan.) Public Law 23-147 constitutes the Commission on Decolonization and mandates that those appointed will hold their seats on the Commission for the life of the Commission. The individuals last holding seats on the Commission are: 1. Governor Felix P. Camacho, who relinquishes his seat and Chairmanship upon the inauguration of Governor-Elect Eddie B. Calvo. 2. Speaker Judith T. Won Pat, who retains her seat as Speaker of I Mina’ Trentai Uno na Liheslaturan Guåhan or, may appoint a Senator to fill her seat. 3. Senator Eddie B. Calvo, who relinquishes his seat upon inauguration as Governor and assumption of the Chairmanship of the Commission. -

Visual/Media Arts

A R T I S T D I R E C T O R Y ARTIST DIRECTORY (Updated as of August 2021) md The Guam Council on the Arts and Humanities Agency (GCAHA) has produced this Artist Directory as a resource for students, the community, and our constituents. This Directory contains names, contact numbers, email addresses, and mailing or home address of Artists on island and the various disciplines they represent. If you are interested in being included in the directory, please call our office at 300-1204~8/ 7583/ 7584, or visit our website (www.guamcaha.org) to download the Artist Directory Registration Form. TABLE OF CONTENTS DISCIPLINE PAGE NUMBER FOLK/ TRADITIONAL ARTS 03 - 17 VISUAL/ MEDIA ARTS 18 - 78 PERFORMING ARTS 79 - 89 LITERATURE/ HUMANITIES 90 - 96 ART RELATED ORGANIZATIONS 97 – 100 MASTER’S 101 - 103 2 FOLK/ TRADITIONAL ARTS Folk Arts enriches the lives of the Guam community, gives recognition to the indigenous and ethnic artists and their art forms and to promote a greater understanding of Guam’s native and multi-ethnic community. Ronald Acfalle “ Halu’u” P.O. BOX 9771 Tamuning, Guam 96931 [email protected] 671-689-8277 Builder and apprentice of ancient Chamorro (seafaring) sailing canoes, traditional homes and chanter. James Bamba P.O. BOX 26039 Barrigada, Guam 96921 [email protected] 671-488-5618 Traditional/ Contemporary CHamoru weaver specializing in akgak (pandanus) and laagan niyok (coconut) weaving. I can weave guagua’ che’op, ala, lottot, guaha, tuhong, guafak, higai, kostat tengguang, kustat mama’on, etc. Arisa Terlaje Barcinas P.O.BOX 864 Hagatna, Guam 96932 671-488-2782, 671-472-8896 [email protected] Coconut frond weaving in traditional and contemporary styles. -

Antonio Borja Won Pat 19 08–1987

H former members 1957–1992 H Antonio Borja Won Pat 19 08–1987 DELEGATE 1973–1985 DEMOCRAT FROM GUAM he son of an immigrant from Hong Kong, at the Maxwell School in Sumay, where he worked until Antonio Borja Won Pat’s long political career 1940. He was teaching at George Washington High School culminated in his election as the first Territorial when Japan invaded Guam in December 1941. Following TDelegate from Guam—where “America’s day begins,” a the war, Won Pat left teaching and organized the Guam reference to the small, Pacific island’s location across the Commercial Corporation, a group of wholesale and retail international dateline. Known as “Pat” on Guam and sellers. In his new career as a businessman, he became “Tony” among his congressional colleagues, Won Pat’s president of the Guam Junior Chamber of Commerce. small-in-stature and soft-spoken nature belied his ability Won Pat’s political career also pre-dated the Second to craft alliances with powerful House Democrats and use World War. He was elected to the advisory Guam congress his committee work to guide federal money towards and in 1936 and served until it was disbanded when war protect local interests in Guam.1 It was these skills and broke out. After the war, Won Pat helped organize the his close relationship with Phillip Burton of California, a Commercial Party of Guam—the island’s first political powerful figure on the House Interior and Insular Affairs party. Won Pat served as speaker of the first Guam Committee, that helped Won Pat become the first Territorial Assembly in 1948 and was re-elected to the post four Delegate to chair a subcommittee. -

![Oceania Is Us:” an Intimate Portrait of Chamoru Identity and Transpacific Solidarity in from Unincorporated Territory: [Lukao]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6169/oceania-is-us-an-intimate-portrait-of-chamoru-identity-and-transpacific-solidarity-in-from-unincorporated-territory-lukao-296169.webp)

Oceania Is Us:” an Intimate Portrait of Chamoru Identity and Transpacific Solidarity in from Unincorporated Territory: [Lukao]

The Criterion Volume 2020 Article 8 6-18-2020 “Oceania is Us:” An Intimate Portrait of CHamoru Identity and Transpacific Solidarity in from unincorporated territory: [lukao] Maressa Park College of the Holy Cross, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/criterion Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, History of the Pacific Islands Commons, Pacific Islands Languages and Societies Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, and the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Recommended Citation Park, Maressa (2020) "“Oceania is Us:” An Intimate Portrait of CHamoru Identity and Transpacific Solidarity in from unincorporated territory: [lukao]," The Criterion: Vol. 2020 , Article 8. Available at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/criterion/vol2020/iss1/8 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by CrossWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Criterion by an authorized editor of CrossWorks. 1 Park The Criterion 2019–2020 “Oceania is Us:” An Intimate Portrait of CHamoru Identity and Transpacific Solidarity in from unincorporated territory: [lukao] Maressa Park College of the Holy Cross Class of 2022 uam, or Guåhan in the CHamoru language, holds a history of traumatic and unresolved militarization imposed by several countries including G the United States. From 1521 to 1898, Spain colonized Guåhan and inflicted near-total genocide (Taimanglo). From 1898 to 1941, the occupier became the United States, which inflicted its own trauma — until 1941, when Japanese forces attacked and occupied the island (Taimanglo). In 1944, the United States attacked the island once more, gaining control over the island and eventually deeming it an “unincorporated territory” — which poet and author Dr. -

Bus Schedule Carmel Catholic School Agat and Santa Rita Area to Mount Bus No.: B-39 Driver: Salas, Vincent R

BUS SchoolSCHEDULE Year 2020 - 2021 Dispatcher Bus Operations - 646-3122 | Superintendent Franklin F. Tait ano - 646-3208 | Assistant Superintendent Daniel B. Quintanilla - 647-5025 THE DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS, BUS OPERATIONS REQUIRES ALL STUDENTS TO WEAR A MASK PRIOR TO BOARDING THE BUS. THERE WILL BE ONE CHILD PER SEAT FOR SOCIAL DISTANCING. PLEASE ANTICIPATE DELAYS IN PICK UP AND DROP OFF AT DESIGNATED BUS SHELTERS. THANK YOU. TENJO VISTA AND SANTA RITA AREAS TO O/C-30 Hanks 5:46 2:29 OCEANVIEW MIDDLE SCHOOL O/C-29 Oceanview Drive 5:44 2:30 A-2 Tenjo Vista Entrance 7:30 4:01 O/C-28 Nimitz Hill Annex 5:40 2:33 A-3 Tenjo Vista Lower 7:31 4:00 SOUTHERN HIGH SCHOOL 6:15 1:50 AGAT A-5 Perez #1 7:35 3:56 PAGACHAO AREA TO MARCIAL SABLAN DRIVER: AGUON, DAVID F. A-14 Lizama Station 7:37 3:54 ELEMENTARY SCHOOL (A.M. ONLY) BUS NO.: B-123 A-15 Borja Station 7:38 3:53 SANTA ANA AREAS TO SOUTHERN HIGH SCHOOL A-38 Pagachao Upper 7:00 A-16 Naval Magazine 7:39 3:52 MARCIAL SABLAN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 7:10 STATION LOCATION NAME PICK UP DROP OFF A-17 Sgt. Cruz 7:40 3:51 A-44 Tracking Station Entrance 5:50 2:19 A-18 M & R Store 7:41 3:50 PAGACHAO AREA TO OCEANVIEW MIDDLE A-43 Cruz #2 5:52 2:17 SCHOOL A-42 San Nicolas 5:54 2:15 A-19 Annex 7:42 3:49 A-41 Quidachay 5:56 2:12 A-20 Rapolla Station 7:43 3:48 A-46 Round Table 7:15 3:45 A-40 Santa Ana 5:57 2:11 OCEANVIEW MIDDLE SCHOOL 7:50 3:30 A-38 Pagachao Upper 7:22 3:53 A-39 Last Stop 5:59 2:10 A-37 Pagachao Lower 7:25 3:50 SOUTHERN HIGH SCHOOL 6:11 1:50 HARRY S. -

Perspectives of Research for Intangible Cultural Heritage

束 9mm Proceedings ISBN : 978-4-9909775-1-1 of the International Researchers Forum: Perspectives Research for Intangible Cultural Heritage towards a Sustainable Society Proceedings of International Researchers Forum: Perspectives of Research for Intangible Cultural Heritage towards a Sustainable Society 17-18 December 2019 Tokyo Japan Organised by International Research Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region (IRCI), National Institutes for Cultural Heritage Agency for Cultural Affairs, Japan Co-organised by Tokyo National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, National Institutes for Cultural Heritage IRCI Proceedings of International Researchers Forum: Perspectives of Research for Intangible Cultural Heritage towards a Sustainable Society 17-18 December 2019 Tokyo Japan Organised by International Research Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region (IRCI), National Institutes for Cultural Heritage Agency for Cultural Affairs, Japan Co-organised by Tokyo National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, National Institutes for Cultural Heritage Published by International Research Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region (IRCI), National Institutes for Cultural Heritage 2 cho, Mozusekiun-cho, Sakai-ku, Sakai City, Osaka 590-0802, Japan Tel: +81 – 72 – 275 – 8050 Email: [email protected] Website: https://www.irci.jp © International Research Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region (IRCI) Published on 10 March 2020 Preface The International Researchers Forum: Perspectives of Research for Intangible Cultural Heritage towards a Sustainable Society was organised by the International Research Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region (IRCI) in cooperation with the Agency for Cultural Affairs of Japan and the Tokyo National Research Institute for Cultural Properties on 17–18 December 2019. -

Coral and Concrete: Remembering Kwajalein Atoll Between Japan, America, and the Marshall Islands

Coral and Concrete: Remembering Kwajalein Atoll between Japan, America, and the Marshall Islands Reviewed by MARY L. SPENCER Coral and Concrete: Remembering Kwajalein Atoll; Between Japan, America, and the Marshall Islands, by Greg Dvorak. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2018. ISBN: 9780824855215, 314 pages (hardcover). Since my first experience in the early 1980’s with the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI), I’ve been stunned by the irony of the ignorance of the average American – including myself - regarding RMI relative to the actual significance of this complex portion of the Micronesian Region to US interests. Now, closing in on almost 75 years since the end of a world war that brought the US and Japan into savage combat in this constellation of hundreds of small islets and islands, RMI continues to quietly move forward, coping in its own culturally determined ways with the hideous impacts of the atomic and environmental assaults generated by the far larger, noisier powers. Today, RMI reaches its own decisions about how to cope with the challenges coming its way. Greg Dvorak, who grew up as an American kid living in the seclusion of the heavily fortified American missile range on Kwajalein Atoll in the RMI in the early 1970’s, opens his childhood memories, as well as his current academic analysis, of this special and secret Pacific Island preserve of the US military. Coral and Concrete is worth the attention of students and scholars of Micronesia and other Pacific Islands, and for the majority of the US reading public who have not heard of Kwajalein nor even the Marshall Islands. -

A Circular History of Modern Chamorro Activism

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pomona Senior Theses Pomona Student Scholarship 2021 The Past as "Ahead": A Circular History of Modern Chamorro Activism Gabby Lupola Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/pomona_theses Part of the Asian American Studies Commons, Ethnic Studies Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, Micronesian Studies Commons, Military History Commons, Oral History Commons, Political History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Lupola, Gabby, "The Past as "Ahead": A Circular History of Modern Chamorro Activism" (2021). Pomona Senior Theses. 246. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/pomona_theses/246 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pomona Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pomona Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Past as “Ahead”: A Circular History of Modern Chamorro Activism Gabrielle Lynn Lupola A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in History at Pomona College. 23 April 2021 1 Table of Contents Images ………………………………………………………………….…………………2 Acknowledgments ……………………..……………………………………….…………3 Land Acknowledgment……………………………………….…………………………...5 Introduction: Conceptualizations of the Past …………………………….……………….7 Chapter 1: Embodied Sociopolitical Sovereignty on Pre-War Guam ……..……………22 -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E1470 HON

E1470 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks July 14, 2003 ANGEL ANTHONY LEON GUERRERO Guerrero Santos, III. Adios Angel. Si Yu’us erick (Fred) W. Rosen. Mr. Rosen was a SANTOS Ma’ase. Naval Officer, a businessman, a hometown f hero, and above all, a patriot. He was a friend to a President and national leaders and a wit- HON. MADELEINE Z. BORDALLO PERSONAL EXPLANATION OF GUAM ness to history. For his contributions to Dalton, Georgia and indeed the history of this great IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES HON. LORETTA SANCHEZ nation, I pay honor to him posthumously; Mr. Monday, July 14, 2003 OF CALIFORNIA Rosen died peacefully on July 14, 2003. Ms. BORDALLO. Mr. Speaker, I rise today IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Fred Rosen was born in 1917 in Brooklyn, New York, the son of Eastern European Jew- to pay tribute to former Guam Senator Angel Monday, July 14, 2003 Anthony Leon Guerrero Santos, III, a tireless ish immigrants. In the 1930s, as the Depres- champion of the rights of the Chamorro peo- Ms. LORETTA SANCHEZ of California. Mr. sion consumed the nation, Mr. Rosen’s broth- ple. Sadly, Angel passed away on July 6, Speaker, on Thursday, July 10, I was unavoid- er Ira moved to Dalton, Georgia seeking op- 2003 after suffering from a degenerative ill- ably detained due to a prior obligation in my portunity in the textile industry by opening the ness. district. La Rose Bedspread Company. Mr. Rosen was Angel was born on April 14, 1959 to Aman- I request that the CONGRESSIONAL RECORD a loyal Bulldog, attending the University of da Leon Guerrero Santos and Angel Cruz reflect that had I been present and voting, I Georgia and playing football there. -

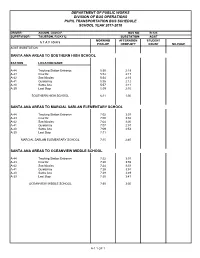

Department of Public Works Division of Bus Operations Pupil Transportation Bus Schedule School Year 2017-2018

DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS DIVISION OF BUS OPERATIONS PUPIL TRANSPORTATION BUS SCHEDULE SCHOOL YEAR 2017-2018 DRIVER: AGUON, DAVID F. BUS NO. B-123 SUPERVISOR: TAIJERON, RICKY U. SUBSTATION: AGAT MORNING AFTERNOON STUDENT S T A T I O N S PICK-UP DROP-OFF COUNT MILEAGE AGAT SUBSTATION SANTA ANA AREAS TO SOUTHERN HIGH SCHOOL STATION LOCATION NAME A-44 Tracking Station Entrance 5:50 2:19 A-43 Cruz #2 5:52 2:17 A-42 San Nicolas 5:54 2:15 A-41 Quidachay 5:56 2:12 A-40 Santa Ana 5:57 2:11 A-39 Last Stop 5:59 2:10 SOUTHERN HIGH SCHOOL 6:11 1:50 SANTA ANA AREAS TO MARCIAL SABLAN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL A-44 Tracking Station Entrance 7:02 3:03 A-43 Cruz #2 7:00 3:02 A-42 San Nicolas 7:04 3:00 A-41 Quidachay 7:07 2:57 A-40 Santa Ana 7:09 2:53 A-39 Last Stop 7:11 MARCIAL SABLAN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 7:15 2:40 SANTA ANA AREAS TO OCEANVIEW MIDDLE SCHOOL A-44 Tracking Station Entrance 7:22 3:57 A-43 Cruz #2 7:20 3:55 A-42 San Nicolas 7:24 3:53 A-41 Quidachay 7:26 3:51 A-40 Santa Ana 7:28 3:49 A-39 Last Stop 7:30 3:47 OCEANVIEW MIDDLE SCHOOL 7:35 3:30 A-1 1 OF 1 DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS DIVISION OF BUS OPERATIONS PUPIL TRANSPORTATION BUS SCHEDULE SCHOOL YEAR 2017-2018 DRIVER: BORJA, GARY P. -

Guam Time Line

Recent Timeline of Coral Reef Management in Guam Developed in Partnership with Guam J-CAT Disclaimer The EPA Declares the Military's The purpose of this timeline is to present a simplifying visual- Expansion Policy "Environmentally Unsatisfactory" and Halts Develop- ment ization of the events that may have inucend the development The US recently proposed plans to expand US Return to Liberate Guam as a military operations in Guam, by adding a new Military Stronghold base, airfield, and facilities to support 80,000 of capacity to manage coral reefs in Guam over time. 1944 new residents. Dredging the port alone will require moving 300,000 square meters of During the occupation, the people of Guam GUAM-Air Force Begins Urunao coral reef. In February 2010, the U.S. Envi- were subjected to acts that included torture, US Military buildup in Guam is Dump Site ronmental Protection Agency rated the plan beheadings and rape, and were forced to as "Environmentally Unsatisfactory" and reduced Air Force begins cleanup of the formerly used adopt the Japanese culture. Guam was suggested revisions to upgrade wastewater The investment price decreased from $10.27 Urunao dumpsite at Andersen Air Force Base By its nature, it is incomplete. For example, the start date is subject to fierce fighting when U.S. troops treatment systems and lessen the proposed billion to 8.6 billion; marine transfers on the northern end of Guam. recaptured the island on July 21, 1944, a date port's impact on the reef. decreased from 8600 to 5000 commemorated every year as Liberation Day. -

Frank Leon Guerrero/Democrat

FRANK LEON GUERRERO/DEMOCRAT QUESTIONNAIRE The deadline to submit written answers is September 30th, 2020 Legislative Candidate Interview Vying For Election To The 36th Guam Legislature A. Real Estate Industry Related 1. The Governor’s office has upgraded the classification of the real estate industry as an essential service during COVID-19 “Condition of Readiness” operating restrictions. However, the Government of Guam agencies that are part and parcel of the real estate industry remain either closed or inactive. (The real estate industry encompasses private sector real estate activities as well as Government of Guam agencies that are involved in the processing of real estate transactions including taxation, recordation, land management interaction, construction and land use permitting, building inspections, building occupancy, and document recordation.). Will you support the preparation and passage of legislation to classify the whole of the real estate industry encompassing both the private sector and related Government of Guam agencies as TRUE ESSENTIAL SERVICES? While I am aware of their being a distinction between “essential services” and “true essential services”. This crisis has forced the awareness of being able to operate the government by implementing a complete digital transformation of distinction government. In many communities across the country obtaining a mortgage and buying a home are processed entirely online. If elected I will work closely with the Association on legislation that will address these concerns. Real Estate is a critical part of our locally grown economy. 2. The Guam Land Use Commission (GLUC) application processing system has been rendered inactive by GovGuam COVID restrictions since March 2020 with no apparent urgency to restore the system to full operation.